BREATHES there a man with soul so dead who never to himself has said, "This is" my own, my native land, but I should like to look about a bit. .. the West Indies ... England and Scotland ...Spain and France and Scandinavia . . . North Africa and Italy and the Near East"?

Or it may be Hawaii and the South Seas with skies infinitely close with stars so large as to seem meretricious.

That is the dream of many Dartmouth men. Instead of realizing it, they seem, many of them, to go to the opposite extreme. They put a fence up about their house. Their travelling is only commuting. They chuck their romantic visions and pride themselves on being realists. Castles in Spain are really dungeons in Spain.

Yes, they say, office routine is deaden- ing. Yes, it takes a long time to earn enough money to break away. A wife and children and particularly the children's education cost far more than estimates made during a felicitous engagement and an ecstatic honeymoon. But there are such things as Duty and Nobility.

The result is "success" and "happiness." Father sticks at office work and finds that he even likes it in a sort of wry ironical fashion. He gets periodical raises in pay, more responsibility and more children, and the children get the finest education money can buy. Mother has the house in her own name.

And then comes the climax. The dream is revived—the dream of foreign lands with exotic boulevards and oceans and jungles. Mr. and Mrs. can indulge themselves a little now, with the children through college. So it will be first class throughout: air clipper and ocean liner, de luxe hotels, and a hired car with a native chauffeur.

They keep saying how wonderful it is, but the excitement seems tame, the museums boring, the landscapes less glamorous, the people noisy and incomprehensible.

The best part is when they see again the Statue of Liberty or their own house intact and twice as beautiful as before. Or perhaps it is when they are looked up to locally as experts on foreign affairs, the result of two full months abroad.

Yet underneath everything is a sort of acrid disappointment. The travel is too little and too late.

What would it have been like if one had taken a whopping chance and risked in- security for one's self, one's wife, and one's children? What price realism? What price security (assuming for the sake of the argument that it still exists)?

SYDNEY CLARK '12 is one Dartmouth man who took that whopping chance. He dreamed and had the courage to live his dream. He liked neither teaching nor business. So he quit both. He wanted to write and to travel. Some luck but not enough. Back to the office. But the dream persisted. A second break. It was not very hard to make it; Mrs. Clark had the courage to urge him on. Never mind about a house and a car and security. Follow the dream.

But what about the children's education? Is it all right to begin it in Rio de Janeiro, change for the States, change again for Paris, for Nice, for Brussels, for Trieste? Keep changing?

After starting Jackie and Don off in Portuguese in South America, the Clarks had a bad moment when they put them in school in Paris. Poor little tikes, they could not speak a word of French and cowered in a corner of the school yard, shy and scared. It was bad for the father and mother to see their children ignored; it was worse to see them persecuted. But father and mother had the courage to stick it out; and so did their kids. Before long these difficulties were things of the past.

In fact, so successful was the Clark experiment in education that Jackie and Don chattered French together by preference, and when they conversed in English before their parents, they did it ceremoniously and sententiously. It was like putting on their best clothes and going to church.

What of the Clark experiment in travel and Writing? That was not so immediately successful. It takes courage to live the dream when it becomes financially night- mared. The temptation is to wake up and conform, to be like other fathers and mothers.

It is true that the Clarks did compromise to the extent of returning to the American treadmill and of using Sydney's strong legs and well.developed track chest to run on it and keep up with others even if he and the others did not get anywhere and had to be content merely in holding their own.

But they did not compromise on their own career. Sydney and Mardi Clark are still living their dream. After pleasant days in the Azores and Portugal, at the mo- ment he is attending that vast festival, Las Falias, in Valencia, Spain. The results will be a new book on Portugal and Spain and their islands (Canaries included). Mrs. Clark sails on April 12 for Naples to meet her husband and help him complete a book on Italy.

A book on the Mediterranean came out in January, the latest of some fifty books that have made Sydney Clark's name famous in the field of travel literature.

DOES blood count? Doctors will probably say that it is impossible to estimate how much one may inherit the nerves and blood which drive one on to continual mobility. At any rate, Syd Clark has forebears who did not stay put.

His grandfather, the Rev. Edward W. Clark, Dartmouth 1844, lived part of his life in Russia.

Syd's father, the Rev. Francis E. Clark '73, founder of the Christian Endeavor Movement, did an enormous amount of traveling, five times around the world and innumerable times to Europe and to South America, all in the spirit of religious idealism. Syd's father took him five times to Europe as a boy; Syd was only six on the first trip.

The father helped his son write his first book, The Charm of Scandinavia, published when the son was 24. The father wrote the sections on Sweden and Finland; the son, on Norway and Denmark. Each tried to prove that his countries were superior. The winner was never satisfactorily declared, but the son admits that his father's name helped to get the book published.

The father's restless blood seemed to be fairly quiet in many of his descendants. One son, the late Eugene F. Clark '01, Professor of German at Dartmouth, and Secretary of the College from 1919 to 1930, went to Australia and New Zealand with his father and mother and lived in Mar: burg, Germany, where he got his Ph.D.

Another son, Harold S. Clark '09, travelled more than most persons but not as much as might be guessed. He too spent a year in Germany, got his degree, taught German, and later switched to Latin.

In the next generation Alden H. Clark '35, a nephew, went on a bachelor trip with his uncles Syd and Harold through France, Switzerland, and Northern Italy and played three-handed bridge with the dummy half wild on balconies overlooking Como and Maggiori.

Francis C. Chase '35, another nephew, has been abroad only once. He travelled in Switzerland and visited his Uncle Syd and his Aunt Mardi when they were living as boarders in an eleventh-century castle in Liechtenstein, that tiny European principality covering only 65 square miles.

Peter Jacobsen Jr. '41, a son-in-law, has never been in Europe. He came from Minnesota and after Dartmouth took post- graduate work at Cal Tech. He now has settled down in Venezuela.

Syd Clark '12 seems to have inherited the insatiable curiosity and the dynamic energy of his father's Wanderlust.

Syd doubts, however, that if his father had kept on living, he would have permitted much self expression in his son. The Rev. Dr. Clark associated sulphur fumes from infernal regions with tobacco smoke, and Syd until his heart attack recently used to run through a pack and a half a day. Liquor was a potion to be favored by Satan and his hellish associates, not by God and his heavenly hosts.

Syd comments frequently in his travel books on the amenities of life, and he likes to advise his readers how to get the utmost out of the travels with a minimum of money. He realizes that the juice of the fermented grape is more widely preferred than that of the unfermented, and he will comment at length on such establishments as smoking rooms on ships, bars, cocktail lounges, wine rooms, beer joints, wine cellars, distilleries, and pubs in a score of countries and in a dozen different languages. In fact, he will refer to such beverages as Heuriger, Moselle and Rhine, White Port and White Rhone, Grandes Fines and Armagnac, Fraises des Vosges and Myrtilles des Vosges, Falernum and Cockage Barbados, Chambolle-Musigny Les Amoureuses and Fleurie Close de la Roilette. To his father that would have been devil's talk.

WITH such a father perpetually back of him and perpetually exerting his strong and wholesome personality, Syd gravitated naturally towards teaching since he had not demonstrated to his or any one else's satisfaction a strong propensity for the ministry. After a trip to Egypt and Scandinavia given him as a reward for his A.B. from Dartmouth, he began by teaching English at the Hill School for three years, and then at the Country Day School in Kansas City for two years. He also was asked to instruct in German, which he did though some of the time he was only one assignment ahead of the class. Neither the boys nor he were soaked in that language.

Teaching was not the answer to his romantic impulses. At the age of 27 Sydney Clark tried the real estate business in Boston with C. W. Whittier, and there he stayed for seven years. Neither Boston nor a realtor's values seemed to satisfy all his romantic urges, and with the money he saved, he and his wife took their first plunge though they had by this time two small children, aged six and two. They set out for Rio, all four, and for the next year Syd wrote short story after short story.

He was gratified and his wife was thrilled when he sold eight of them to such magazines as Argosy and the Woman's World and to some British magazines of the same persuasion.

Then they took their second plunge. The Clarks at the end of a year still had a little money left, and so off they swooped slow motion on a little ship for Trieste. Syd was now 35 years old at a time when most young men are well up the ladder of success. The urge to write drove him on to Paris and from Paris to Nice.

All the time Syd was writing short stories and wandering about France trying to find color and a human comedy to write about. The color was there all right and the drama, but Syd was not the first American to find out that writing is an art as difficult as music. Short story writer or violinist, a man tries to make music to move the heart of man and succeeds only in making a dull noise like beating on a cracked drum.

It looked like defeat for Mr. and Mrs. Sydney Clark. They faced it, and back they went to Boston and to the life of real estate and a suburb. Syd stuck it out two years more. He was approaching 40, an age when most men hug to their chests what- ever success they have had in business, for they know only too well that a break now is a crackup.

So much did Syd hate confinement, how- ever, that he saw that it would be a crackup without a break. Again with the aid and connivance of Mrs. Clark, he defied convention and respectability for the third time.

To vary adventure, this time the Clark family chose Belgium and settled down in Brussels, but it was only a short stay after all, and they traipsed all over Europe. Syd feared that he might not become a creative writer of fiction and started a travel book. It did not go. Only one publisher had anything good to say about it, but he did not want to buy it, though he liked the buoy- ancy of Sydney Clark's prose style and actually gambled enough on it to commission the writer to do a book on Austria.

Its title was Old Glamors of New Austria. "It was a perfectly dreadful title," remarks Clark candidly, "but, Hallelulia, it got me started. It was a discursive book, not a travel book."

Then with such a stimulus as being a full-fledged author of a book, he set to and produced two more, The Cathedrals ofFrance and Many Colored Belgium.

But the publication and sale of even three books is not going to be enough to provide food for four persons, housing and heat, education and diversion, and Syd had to submit himself again to that concentration camp called an office.

With the prestige of authorship Clark could now move on from the stuffiness of Boston to the briskness of New York and the romance of radio work and script writing for N. W. Ayer & Son. The logic of the situation calls for rapid promotions from $3500 a year to $35,000. Trust Sydney Clark not to run true to form.

BUT the three books had become noticed. At the late age of 42, Clark got his great chance. The Robert M. Mcßride Company of New York commissioned him to do his now well-known Fifty Dollar Series. They were called France on Fifty Dollars, Germany on Fifty Dollars, and McBride and Sydney Clark signed contracts for fourteen of these books. Sydney added the fifteenth, Austria. The book was due to be published on March 15, 1938. On March 11 Hitler marched in. Austria no longer existed; it was merely an outpost of Ger- many called the Ostmark. Austria on FiftyDollars was even before being published so ludicrously out of date as to make Sydney and Mardi Clark sit down and weep, if they had been the least bit inclined to- wards that kind of self expression.

This episode has become a sort of family joke, and all the Clark relations kid Sydney about the dangers of the publication of one of his books on the world situation. Three times now he has had a book ready to appear in print when three times the country about which he was writing went down the drain or burst out into the flames of revolution.

"I should like to capitalize on my nuisance value," remarks Clark musingly. "Why should I not get large sums of money from countries if I promise not to write about them?"

He shakes his head with something like grimness. "Look here," he says with concern. "It is now December 1951. I have made two trips all over the Mediterranean from Madeira to Lebanon to write a book on the Mediterranean [reviewed in this issue]. Among the fifty books I have written, it is my biggest and most complicated one. I have worked harder on it than on any other in my life. This book is to be published on January 14, 1952. You see the logic of the situation. Egypt is stewing in a hell broth of revolution. The entire Near East is getting up its fighting spirit. The date when the Mediterranean is going to explode sky high and hell deep is obviously January 12, 1952, two days before my book is to be published, but time enough to make it perfectly obsolete despite the years of work and writing I have put into it."

Incidentally, Sidney Clark's son Donald '43 and his daughter Jacqueline, whose husband. Peter Jacobsen Jr. '41, is a geochemist and geophysicist and works for the Creole Petroleum Corporation in Caracas, Venezuela, assist their father in his books. Donald designs the dust jackets and Jackie does the maps.

During World War II the Government found that it could use the knowledge of so many countries, especially South American ones, to good purpose, and Syd Clark went to work in the Pentagon. There he served on a subsidiary committee of the General Committee on Cultural Relations with Latin America in which Nelson Rockefeller was so much interested. Syd helped to decide what books and articles written in Spanish and Portuguese should be translated and sold to North American magazines to give the United States a better understanding of how South Americans feel and live.

Syd also was Editor of the Signal Corps in the Pentagon for a year and a quarter and quit on VJ day. He was eager to return to Europe and write books about what had happened to the countries he knew and loved. An indication of his interest and vitality may be seen in the tact that since VJ day he has written ten new books and revised three old ones.

To persons who only with difficulty can write a four-page letter (and they are in the majority everywhere), such pro- ductivity seems astounding. Sydney Clark could not be so facile if he did not have Mrs. Clark to help him. The process of turning out a book begins first with travels in the foreign country under investigation. Sometimes Mrs. Clark goes, sometimes not; it depends on how the family finances are. On the job abroad Syd puts in more than a full day's work. A businessman gets off lightly, for even with a commuter's schedule from, let's say, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., he puts in fewer hours than the Clarks.

Everything concerned with travel is work, for his travel books are practical affairs with all questions, even the stupid and trivial questions, legitimate and worthy of comment. What kind of bags and trunks? Steamer cabins and plane seats? Foreign money? Proper tips? Food and drinks to enjoy and to avoid? Museums, monuments, theatres, parks, and moving pictures to see? Night life? Customs? Language barriers? Guides? You know, the thousand and one things which every traveller is happier to know about when he leaves the order and comfort of his own home.

Syd and Mardi scurry about hither and yon, and if there is any time that they are sitting down, they take notes for future reference. Back home in Sagamore Beach, Syd works at a little table in an alcove of his bedroom beside a shelf filled with his own note books, maps, dictionaries in English and foreign languages, encyclopedias, magazines with marked articles, newspapers from abroad.

He composes in longhand and uses note books taller than they are wide with rings at the top. He uses the lower page for the main body of his writing and the upper page for corrections, revision, questions to be looked up. Eight or ten of these notebooks may make a travel volume.

Mrs. Clark's job is to decipher her husband's hieroglyphics and to do his typing. To guarantee that he not be disturbed when he is in the high-pressure mood of meeting a deadline, she allows him perfect peace to stare at his maps and notes and at the sea outside which may show a tanker or a collier not long out of the Cape Cod Canal heading for Boston. If there is an atlas to be found from the main library downstairs, she will find it. If there is an electric light to be fixed, she will fix it. Indeed it will not be Mr. Clark who replaces a blown fuse; it will be Mrs. Clark though she might not have dreamed in the days when she studied violin at the New England Conservatory of Music that she would become an expert electrician.

How can a man work so hard when he is 61? Well, perhaps he can work; it's more likely play which may cause the trouble. On August 5 when on the tennis courts, Syd was trying to beat his older brother Harold '09, aged 64, retired head- master of the Rumson School, and had a heart attack. He lay down on a bench, but he refused to stay put. He thought that he was simply soft from so much sedentary work at his desk. Up he got and played some more. That did it. Yes, said the doctor, it is definitely a coronary thrombosis. Bed for you, sir. Flat on your back. Don't even raise your arm to feed yourself. Mrs. Clark has been your left arm right along. Let her now be your right arm also.

Syd stood that for three weeks. His only exercise was blinking. He even quit his go cigarettes a day. He consented to remain quietly in Sagamore for six months. He certainly kept off the tennis courts, and he went only occasionally to Boston and New York.

By the time December came, he was full of bounce. Let a visitor mention a foreign country, Syd would pop out of his chair and dart towards his bookcase. He would open it impulsively, flutter the leaves, poke a vital forefinger at a particular passage, and then sit forward (not back) to reminisce about that wonderful day. He was soon to fly to Spain. Upstairs lay the notebooks about Italy where he has been twice and where he is going in the spring with his wife for more material for his unfinished book. He talked about Japan. How that country has changed since Pearl Harbor! It used to be our enemy. Now it is full of our little Japanese brothers. What are they thinking about? What's life like in Tokyo, Yokohama, Hiroshima, and Gifu? How little Americans know about Nagoya, which has a population of nearly three million people, Sapporo with more than three, or Shizuoka with two!

Perhaps the book on Japan may turn out to be travel literature for the American fireplace and armchair. Europe will still be the magnet. Where does Clark think that an American should travel if he wishes to enjoy to the full European civilization and color in friendly and happy surroundings? Especially an American with a modest income?

"Spain above all," says he. "It is still fabulously inexpensive. A person can live like a prince in the luxurious hotels of Madrid and Barcelona like the Ritz and the Palace for $3 a day which includes everything. Portugal and Austria are also attractive to a man who wants foreign life without incurring too much expense."

Clark admits with regret that the carefree, romantic days of Europe before World War I and even of Europe between the world wars are difficult to experience and may never again be realized. Inflation plays havoc with tourists; it plays worse havoc with natives.

England, for example, is expensive and austere, though its countryside is still delightful. Italy is expensive and torn by economic strife. France, Belgium, and Switzerland are all costly though Switzerland which has escaped inflation seems much more reasonable than it used to.

What would Clark do if he could just luxuriate and not think of a 15-hour day gathering materials for a travel book, writing, searching for pictures, checking figures, and reading proof?

"I hope that you will not think me a platitudinarian," he says, "if I say that France is still wonderful and that Paris is still enchanting."

Does he have any regrets about his travels?

"Yes," he says. "They have been too circumscribed. I have been twice to Hawaii but no farther east. I have been to Australia and New Zealand but not to China and India. I have not gone beyond Damascus in Syria and Ankara in Asiatic Turkey. Africa I know only from Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya."

Clark will be 62 on his next birthday. Does he look forward to retirement?

"Most emphatically not," he says. "I love travel and I love to write books. I hope that I shall exhibit a minimum of common sense about my private life and keep going for many years.

"No," adds Clark thoughtfully. "I do not yet wish to retire and settle in, beautiful though my Sagamore Beach may be. I have lived four years in Paris—not the tourists' Paris. I have written eight books about Paris, some of them in Paris cafes in Montparnasse.

"Yes, I still like mobility and liberty. I like the freedom, for example, of entering a Montparnasse cafe at 7 in the morning for my morning coffee and writing from then until midnight at the same table with occasional re-orders of coffee and cognac to keep me and my waiter happy."

But it is not only Paris. It is Amsterdam with its concentric patterns. It is Stock- holm with its clean fresh and salt water. It is the Riviera, his first love. It is Venice, not the Venice of the Grand Canal and the Lido but of the little streets which one travels on foot with their gayety and life—little streets not on maps which lead one with teasing indirection ever closer to the mystery of Italy. It is Liechtenstein with its romantic castle on the East Bank of the Rhine. It is Velden and the Worther See and Carinthia and all the lovely Austrian lakes.

If the Near East is untouchable because of its red-hot iron curtain, there is Japan. Clark's publishers are talking about another book. The Mediterranean volume has just appeared. Clark flew alone to Portugal and Spain this winter. The volume on Italy should be finished in 1952.

Sydney Clark's gaze goes across the Atlantic to his castles in Spain. They did not turn out to be dungeons in Spain as some of his practical friends had warned him. Aided and abetted by his wife, he has run risk after risk and found happiness for himself, for her, and for their children.

Why not pagodas in Japan in 1953?

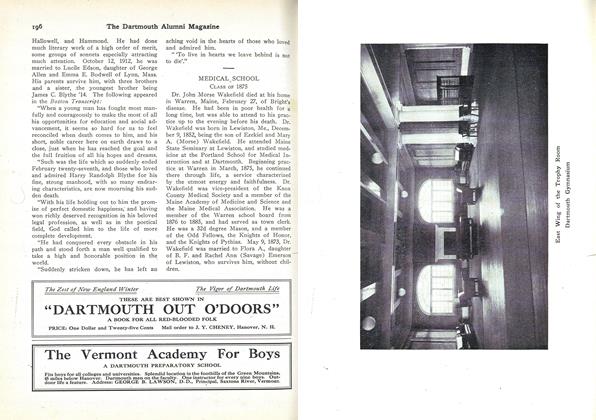

SYDNEY CLARK '12 AT HIS HOME AT SAGAMORE BEACH, CAPE COD

AS CAPTAIN OF THE 1911 DARTMOUTH CROSS-COUNTRY TEAM, Sydney Clark sits front and center.Other team members are (I to r), seated: Wallace McCoy '13 and Bob Hastings '14. Standing: AlvahHolway '12, Howard Ball '13, Franz Marceau '14, Lester Bacon '14, and Paul Harmon '14.

THERE'S STRONG DARTMOUTH REPRESENTATION in this Clark family picture. Left to right: Sydney Clark's brother-in-law; his daughter-in-law Dorothy; his son, Donald E. Clark '43; Mr. Clark; his wife Mardi; his nephew's wife; his nephew, Francis C. Chase '35; his brother, Harold Clark '09; Harold's daughter-in-law; and Mrs. Harold Clark. Directly in front of Don is Sydney Clark's grandson Jonathan.

QUEEN OF THE SNOWS: Miss Diana Weeks of York, Pa., reigned over Dartmouth's 42nd annual Winter Carnival. She is shown above with 5-year-old Helen Anne Rouselle, who skated at Outdoor Evening.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTelevision and Education

March 1952 By EDWARD LAMB '24 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1952 By Conrad S. Carstens '52 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1952 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

March 1952 By MICHAEL H. CARDOZO, JOHN B. WOLFF JR., CHARLES D. DOERR

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleTHE NEW FRONTIER

February 1953 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureSoldiers As Policy Makers

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

JUNE 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Books

BooksOFF THE SAUCE.

NOVEMBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSCENERY OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS.

MARCH 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

MAY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21