The Canadian Arctic Islands: North America's Last Petroleum Province?

May 1960 ANDREW H. McNAIR,PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY

EARLY last year, one of the most extensive land rushes in the history of the petroleum industry took place ' above the Arctic Circle. Within the space of a few weeks petroleum and natural gas exploration permits were filed for more than eighty million acres in Canada's inaccessible and relatively frigid Arctic Islands.

This precipitous rush for petroleum rights occurred at a time when oil companies were faced by depressed prices for their products, caused mostly by an oversupply of crude oil. Among the contributing factors motivating their participation in the widescale and perhaps poorly timed rush for prospecting rights in Canada's Far North was the successful navigation of the Arctic Ocean basin by the Skate and Nautilus. This feat suggested the possible future use of large, atomic-powered submarines in transporting petroleum under the sea-ice in the straits between the islands and the northern sea lanes which guard the approaches to the Arctic Islands.

Other factors which prompted the land rush are mostly of a geological nature and are the basis of this discussion. For a long time geologists have known that parts of the Arctic Islands were underlain by sedimentary rocks similar to those which had produced oil in other parts of the world. In 1954, I and two Canadian geologists, Y. O. Fortier and R. Thorsteinsson, published a paper in the Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists which outlined the major geological provinces of the Arctic Islands and summarized existing information on the rocks and structures of the region. The petroleum possibilities were also evaluated in a general way.

The Canadian Geological Survey began a widescale, systematic geological survey of the Islands in 1947. Using Eskimo dog-teams, canoes, helicopters and light fixed-wing aircraft for transportation, Canadian geologists have surveyed most of the archipelago. Preliminary reports and regional reconnaissance maps published by the Canadian Survey added a great deal of geologic information which could not be gleaned by the most thoughtful interpretation of the scattered and sometimes conflicting statements which had been written by the few explorers who had travelled in the area prior to 1947.

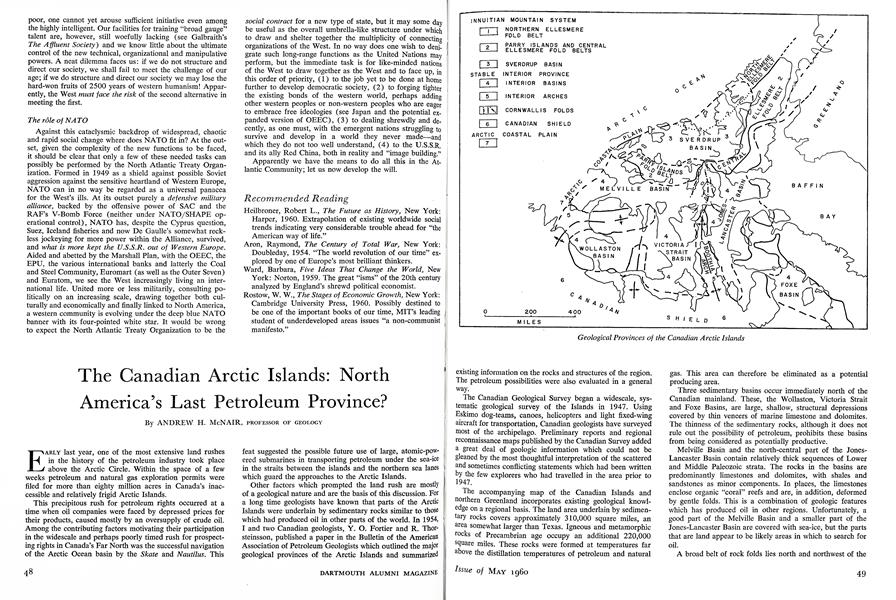

The accompanying map of the Canadian Islands and northern Greenland incorporates existing geological knowledge on a regional basis. The land area underlain by sedimentary rocks covers approximately 310,000 square miles, an area somewhat larger than Texas. Igneous and metamorphic rocks of Precambrian age occupy an additional 220,000 square miles. These rocks were formed at temperatures far above the distillation temperatures of petroleum and naturalgas. This area can therefore be eliminated as a potential producing area.

Three sedimentary basins occur immediately north of the Canadian mainland. These, the Wollaston, Victoria Strait and Foxe Basins, are large, shallow, structural depressions covered by thin veneers of marine limestone and dolomites. The thinness of the sedimentary rocks, although it does not rule out the possibility of petroleum, prohibits these basins from being considered as potentially productive.

Melville Basin and the north-central part of the JonesLancaster Basin contain relatively thick sequences of Lower and Middle Paleozoic strata. The rocks in the basins are predominantly limestones and dolomites, with shales and sandstones as minor components. In places, the limestones enclose organic "coral" reefs and are, in addition, deformed by gentle folds. This is a combination of geologic features which has produced oil in other regions. Unfortunately, a good part of the Melville Basin and a smaller part of the Jones-Lancaster Basin are covered with sea-ice, but the parts that are land appear to be likely areas in which to search for oil.

A broad belt of rock folds lies north and northwest of the Melville and Jones-Lancaster Basins. The folded belt is exposed in two areas. The western or Parry Islands Fold Belt is 320 miles long. Its eastern counterpart, the Central Ellesmere Fold Belt, is 800 miles in length. These two areas are the inner part of a major, complex set of mountain structures, the Innuitian mountain system, which extends from North Greenland in a broad arc-shaped course, almost to the Arctic Ocean.

Comparatively little is known about the geology of the Central Ellesmere Fold Belt. In general, it appears to have had a long and complicated history of sedimentation and deformation. Available information suggests it has thick deposits of sediments which are not notably petroliferous, and that any hydrocarbons which may have existed in the rocks have been destroyed during metamorphism.

The Parry Islands Fold Belt is relatively well known from the preliminary reports and maps published by the Canadian Geological Survey. It contains sedimentary rocks, more than 22,000 feet thick, representing continuous deposition extending in age from the Middle Ordovician through the Upper Devonian. These sediments have been deformed into large folds which were later beveled by erosion. The truncated edges of the folds crop out on the surface as conspicuous sinuous bands.

Fold belts have not had a highly productive history in other places where they have been tested by drills. The reason may lie in the absence of oil source beds and destruction of oil and gas during times of mountain-building deformation. However, petroliferous, organic-rich shales and shaly limestones are widespread in the Parry Islands Fold Belt. The folds, in certain places, are not highly deformed, and it is possible that the oil which might have been present before folding was not lost during the belt's deformation.

The Sverdrup Basin lies north and northwest of the Parry Islands and Central Ellesmere Fold Belts. This basin is approximately 750 miles long and has a maximum width of 250 miles. It is filled with marine and non-marine strata of Upper Paleozoic and Mesozoic age, which were deposited on top of the deformed and eroded structures of the Innuitian mountain system. Basaltic lava flows and basic igneous rocks are common in the northern part of the basin. The maximum thickness of sediment appears to be more than 15,000 feet. The Sverdrup Basin contains a number of gypsum structures which thrust their way through the overlaying sediments a manner similar to the salt plugs of Texas and Louisiana. The latter have controlled the location of many oil fields including the recently discovered Gulf Coast off-shore pools! The Sverdrup Basin, particularly in areas which contain thick sequences of marine rocks, appears to have the prerequisites needed for petroleum production.

The North Ellesmere Fold Belt is the least-known area in the archipelago. It apparently consists of metamorphosed and highly deformed rocks of a type which has never yielded commercial quantities of oil or gas.

The outer, western edges of the islands are covered by thin deposits of sands and gravels of the Arctic Coastal Plain. These sediments are of such recent age that they contain abundant specimens of unfossilized wood. The recent age as well as the character of the sediments precluded their being petroliferous. However, it is possible that this area might contain oil in the sediments which are buried beneath its sands and gravels.

On the basis of the geology of the Arctic Islands, imperfectly known as it is, it would appear that the area has considerable potential as a possible petroleum producing province. This does not infer that the Arctic Islands will be able to compete with the low-cost oil which is now produced in Venezuela, the Middle East or North Africa. As these regions are depleted and as the world-wide demand for petroleum increases, the Arctic Islands could become competitive.

The transportation of crude oil, except for a few comparatively accessible areas, poses the most difficult problem in the future development of arctic oil. Even if petroleum is discovered in the Canadian Islands, its economical and yearround transportation to populated centers will depend on the development of nuclear-powered submarine tankers. Because of the remoteness of the country and the difficulties of transporting drilling equipment, it may be twenty years before the area can be tested systematically. It will be interesting to see whether this region in fact contains large reserves of crude oil, and to watch the development of transportation methods if large oil deposits are found.

Geological Provinces of the Canadian Arctic Islands

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Poetry of History: William Faulkner's Image of the South

May 1960 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR., -

Feature

Feature"What We Are After"

May 1960 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Feature

FeatureNATO in Trouble

May 1960 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31, -

Feature

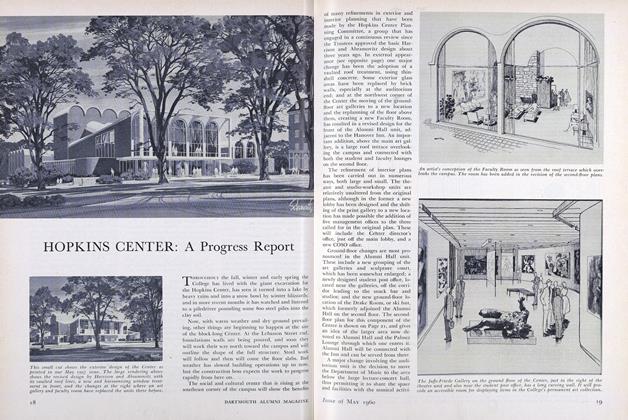

FeatureHOPKINS CENTER: A Progress Report

May 1960 -

Feature

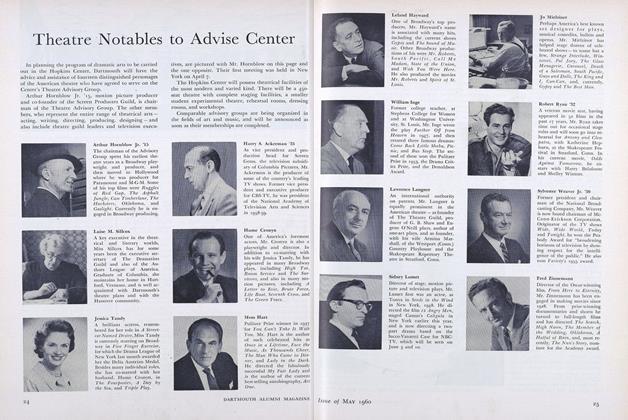

FeatureTheatre Notables to Advise Center

May 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1960 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

Features

-

Feature

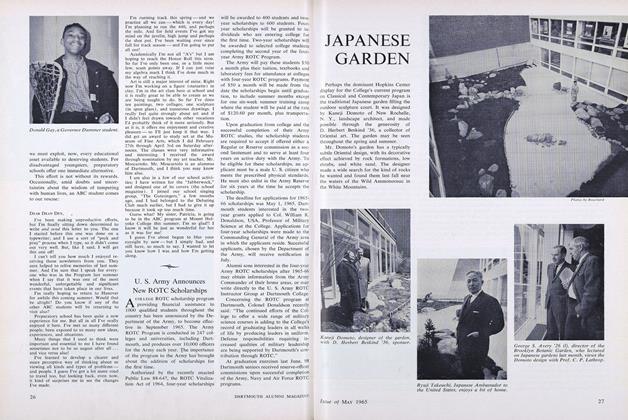

FeatureJAPANESE GARDEN

MAY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

DECEMBER 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

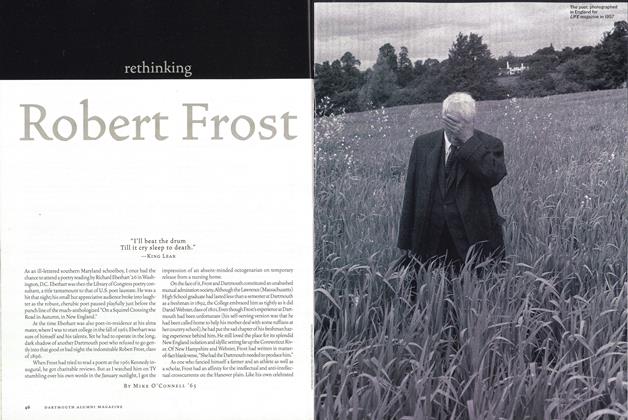

FeatureRethinking Robert Frost

Nov/Dec 2003 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

FEATURES

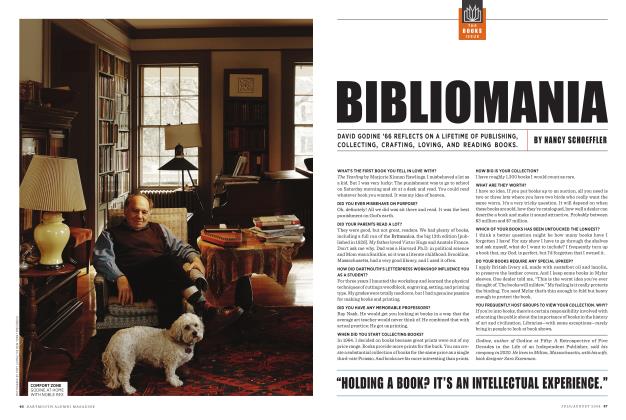

FEATURESBibliomania

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of a Liberal Education

December 1955 By PROF. ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Feature

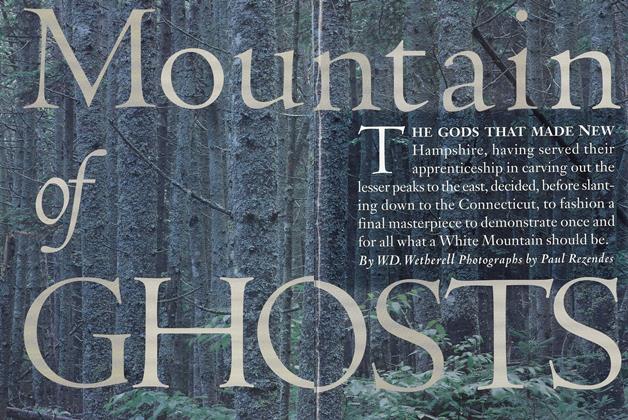

FeatureMountain of Ghosts

JUNE 1997 By WD. Wetherell