PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY

IF the North Atlantic Treaty Organization did not exist, it would have to be invented. Unless the nations of the western world hang together, they will all hang separately (to paraphrase Ben Franklin). Facing both a chaotic and revolutionary world and the shrewd conspiratorial movement of the communist bloc exploiting this situation, the traditional political, economic and social institutions of western society seem hardly adequate.

It is, of course, completely false to ascribe the swirling turmoil of the contemporary world scene, in which we find ourselves, solely to communist machination, as the simpleminded have tended to do. Actually the communist revolutionaries dedicated to their (to us unhappy) future Utopian earth merely exploit a situation which is revolutionary in and of itself. In short, the West faces a worldwide systemic revolution (basic changes in the political, economic and social status quo) which is already farther advanced than most of us are either aware or will admit.

Let us briefly run through four interwoven elements of this twentieth century world revolution: (1) new ideologies, (2) the explosive growth of reliable knowledge and technology, (3) the expansion of government, and (4) the new "managerial" elite. These four interconnected elements are by no means the only aspects of the changing status quo-but they are crucial and clear component parts of the emergent "Brave New World."

1. Nationalism

Nationalism is still the most powerful ideological force motivating men in our time (although international communism is running a close second). The combination of the state with the nation has proved for the western world from the seventeenth century on to have been an important constructive factor lifting our civilization out of feudal/medieval incompetence to the bustling technological society of today. The western industrial revolution is inconceivable certainly in its initial phases without a reciprocal relationship with the nation state: nations built industry and industry built nations. On the other hand it is probably not beside the point that the wars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, based largely on "nation-worship," have been the bloodiest in human history. In an interdependent world tied tightly together by electronic communication and massive (as well as rapid) transport, the rather small nation states of western Europe make little sense economically or politically today-even if the sprawling federation which is the United States still makes sense. But even in the latter case, as a have-not nation with respect to raw materials and quite incapable of survival as "Fortress America" in an unfriendly world, we too in the U.S.A. approach the stage when the structure and concept (or fiction) of the sovereign nation state is incapable of performing adequately the needed economic and political functions required for survival—not to mention "progress" today. In short, we in the West must develop new international governmental structures in order to avoid the gloomy prognostications of a Spengler or a Toynbee.

Without bothering to elaborate the chicanery (as well as the denial of humanistic values) in both theory and practice of the Soviet constitution, it is worth while pondering their concept of an international political and economic state joining an expandable number of "nations" culturally defined. Both the Nazis with the Neue Weltordnung and Imperial Japan of World War II with the Greater East Asia CoProsperity Sphere faced the problem of building a supra- national society. Neither of the three solutions were or are attractive to western society but that does not erase the problem of the inadequate nation state which still must be faced by the West today.

Underdeveloped peoples clamoring for independent nationhood seemingly have little conception of what they face. At the outset, one must recognize the fact that the entire excolonial world is hell-bent for independence and industrialization. Suffice it to say that this bifurcated drive almost reaches the point of an illogical mania or compulsion—beyond rational thought. But there is not the slightest hope of dissuading these emergent peoples from this one-way path"free to ruin themselves and independent to starve to death," as one cynic observed. On the other hand—even though nationalism may be an anachronistic ideology for sophisticated society—it may well have a decided functional value in lifting simple tribal peoples out of primitive sloth toward a realization of larger horizons.

2. The explosive growth of reliable knowledge and technology

Analysis of the process of invention makes quite clear that there is geometric, rather than arithmetic, progression in the development of new technical knowledge—with all the complex implications for political, economic and social life that this implies. Within the compass of this short essay, it is impossible other than to indicate a few of the more dynamic and immediate potentialities in pure mechanical technology:

(a) nuclear weapons and supersonic delivery systems (what sense do nation states make under these circumstances?)

(b) further development of electronic communication and large-scale rapid transport (linking the world still more closely)

(c) automated factories and electronic brains (with all the implications for education, class structure and "the new leisure")

(d) the world population explosion due to public health techniques (six billion inhabitants of the earth anticipated for the year 2000—70% non-white).

But this is only mechanical technology! What of the new rationalistic and interrelated skills for manipulating men to first bureaucratic organization and second as individuals by improved conditioning and in groups by mass communication techniques? The managerial skills in building and ad- ministering large-scale organizations, formerly impressionistic and inspirational, are being increasingly rationalized. After elementary studies of bureaucracy (perhaps overstressing both the rationalistic as a countervailing effort to the folkimpression of inefficiency and red tape), newer studies have ferreted out the informal irrationalities of bureaucratic structure and are setting traps and stratagems to harness ration- ally this irrationality for the formal goals. The U.S.S.R. is a giant bureaucracy; it continues to exist and even develop contrary to the prognostications of many. General Motors, U. S. Steel, Harvard University, the Catholic Church, and S.A.C.—all five giant bureaucracies according to the latest available information, apparently too are thriving. There is no evidence to suspect that it will not be possible in the future to design and run even larger (and even more efficient) bureaucracies. The point of diminishing returns is simply not yet in sight in the rational building and administering of large-size organizations. Further, if in addition to bureaucratic techniques, man adds new conditioning methods (even such now fanciful ideas as sleep and chemical conditioning) and bases his activities on motivational research (despite all the current nonsense about M.R. as it is stereotyped), the possibilities for coordination and motivation of mankind in hordes may not be too far away. The behavior of mass media, capped by the omnipresent television screen, as well as recent elections suggest that it is not inconceivable that a president can be sold like soap. What does this mean for the concept of the rational man exercising his rights in a democratic society mechanically geared to majority rule? It might be added parenthetically that it seems hardly likely that underdeveloped peoples will be much impressed by western democratic society which has given recent evidence of its incompetence by Suez, two "revolutions" in France, and a United States which has allowed its "image" to be completely outshone on the world stage by the U.S.S.R. This latter despite our vaunted mastery of "Madison Avenue" techniques!

3. The growth of government

Despite the theories of Karl Marx and the desires of western conservatives, the governmental institution is rapidly extending its responsibilities. In the West it tends more and more to include (a) the fundamental control and direction of economic functions and (b) the social welfare of the individual citizen. This may be a "good" or "bad" thing depending on one's value system, but no one can deny that this take-over is a real thing. Berle and Means some years ago elaborated the thesis of the split between ownership and control and established in the sophisticated public's consciousness the awareness that managers managed and that owners merely had residual control powers (despite the nonsense about "corporate democracy"). For example, recently management of AT&T owned .01% of that fantastic corporation and the management of Douglass Aircraft (often thought of as a family concern) merely .77%. It was recently estimated by a prominent economist that 1000 key Americans controlled 50% of the world's non-agricultural production. If to this picture is added the enormous immediate fact of banker controllers of the burgeoning mutual, insurance and pension funds, one may grasp the implications of what is meant by a "socialized-capitalist" managerial economy. One further mental step is now needed: who controls the controllers? Again it has been recently estimated that two-thirds of American economic life is "controlled" in one way or other by government! Running all the way from government in business (Panama Canal and the Parcel Post) to mixed enterprises such as the AEC and the Rand Corporation to the FCC, SEC and finally the Department of Agriculture, Pure Food Laws and tariffs. Europe, of course, is farther along than we; one risks extinction on the streets of Paris by either a Renault or a Volkswagen—neither of which is presently a private undertaking. Barbara Ward, the British economist, has gone so far as to claim that it is not "ownership but enterprise" that is crucial in the economic sphere today. It seems more than likely that, whether Nixon or the Democrats capture the executive part of our federal government this year, this process of increased government "interference" will be speeded up—the desires of many good citizens to the contrary.

In addition to the increasing directive role of government, we witness a commensurate increase in governmental social welfare functions. Former responsibilities of the family, the church and commercial enterprise are now seemingly gravitating toward government as the institution capable of performing these needed functions reasonably well today. I shall do no more than list several areas of increasing governmental responsibilities in the U.S.A.: (a) urban redevelopment and housing; (b) old age pensions and publichealth, including health insurance probably to be introduced here in connection with old age pensions and possibly as part of a mixed system of various forms of commercial, nonprofit and industrial insurance coordinated under a national system; (c) culture and recreation, Lincoln Center and the potential Cape Cod National Park come to mind; (d) educacation, federal financial aid on a large scale as the need is finally appreciated and local tax sources dry up. Behind this some sort of national plan may well be slowly developed.

In passing, it should be stressed that the uncommitted and largely underdeveloped world is already adopting and adapting the industrial revolution to its purposes as a governmentally planned, directed and largely-owned operation. It is, moreover, clear that social welfare (such as it is in such lands) will be from the start largely a function of the state as it moves beyond family and village responsibilities. One is constrained to ask under these circumstances whether the U.S.S.R. or the U.S.A. serves as a "better" model for such a development?

4. The ruling elite

It goes against both the American grain and American folklore to discuss elite control of society. But Jefferson, certainly Hamilton and Washington as well as numerous others of the founding fathers, saw that a trained leadership group was needed to form our nation and so acted to nudge reluctant colonial farmers and "mechanics" along the tiring road toward the independent nation state. The problem of democratic leadership (especially in view of the increased manipulative capabilities of the present) is perhaps the crux of the survival of the West today. Where does one find talent, train it, motivate it, arm it with power and ultimately control it, to design, build and run the increasingly complex society of the future? There seems little question that a loosely structured federation as the government for a nation state is having great difficulty facing remorseless totalitarian competition. And it becomes increasingly probable that a western elite must be developed to run something larger than nation states.

The location of talent in the United States gets better and better—although among the psychologically underprivileged poor, one cannot yet arouse sufficient initiative even among the highly intelligent. Our facilities for training "broad gauge" talent are, however, still woefully lacking (see Galbraith's The Affluent Society) and we know little about the ultimate control of the new technical, organizational and manipulative powers. A neat dilemma faces us: if we do not structure and direct our society, we shall fail to meet the challenge of our age; if we do structure and direct our society we may lose the hard-won fruits of 2500 years of western humanism! Apparently, the West must face the risk of the second alternative in meeting the first.

The rôle of NATO

Against this cataclysmic backdrop of widespread, chaotic and rapid social change where does NATO fit in? At the outset, given the complexity of the new functions to be faced, it should be clear that only a few of these needed tasks can possibly be performed by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Formed in 1949 as a shield against possible Soviet aggression against the sensitive heartland of Western Europe, NATO can in no way be regarded as a universal panacea for the West's ills. At its outset purely a defensive militaryalliance, backed by the offensive power of SAC and the RAF's V-Bomb Force (neither under NATO/SHAPE operational control), NATO has, despite the Cyprus question, Suez, Iceland fisheries and now De Gaulle's somewhat reckless jockeying for more power within the Alliance, survived, and what is more kept the U.S.S.R. out of Western Europe. Aided and abetted by the Marshall Plan, with the OEEC, the EPU, the various international banks and latterly the Coal and Steel Community, Euromart (as well as the Outer Seven) and Euratom, we see the West increasingly living an international life. United more or less militarily, consulting politically on an increasing scale, drawing together both culturally and economically and finally linked to North America, a western community is evolving under the deep blue NATO banner with its four-pointed white star. It would be wrong to expect the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to be the social contract for a new type of state, but it may some day be useful as the overall umbrella-like structure under which to draw and shelter together the multiplicity of connecting organizations of the West. In no way does one wish to denigrate such long-range functions as the United Nations may perform, but the immediate task is for like-minded nations of the West to draw together as the West and to face up, in this order of priority, (1) to the job yet to be done at home further to develop democratic society, (2) to forging tighter the existing bonds of the western world, perhaps adding other western peoples or non-western peoples who are eager to embrace free ideologies (see Japan and the potential expanded version of OEEC), (3) to dealing shrewdly and decently, as one must, with the emergent nations struggling to survive and develop in a world they never made—and which they do not too well understand, (4) to the U.S.S.R. and its ally Red China, both in reality and "image building."

Apparently we have the means to do all this in the Atlantic Community; let us now develop the will.

Recommended Reading

Heilbroner, Robert L., The Future as History, New York: Harper, 1960. Extrapolation of existing worldwide social trends indicating very considerable trouble ahead for "the American way of life."

Aron, Raymond, The Century of Total War, New York: Doubleday, 1954. "The world revolution of our time" explored by one of Europe's most brilliant thinkers.

Ward, Barbara, Five Ideas That Change the World, New York: Norton, 1959. The great "isms" of the 20th century analyzed by England's shrewd political economist.

Rostow, W. W., The Stages of Economic Growth, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1960. Possibly destined to be one of the important books of our time, MIT's leading student of underdeveloped areas issues "a non-communist manifesto."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Poetry of History: William Faulkner's Image of the South

May 1960 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR., -

Feature

Feature"What We Are After"

May 1960 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Feature

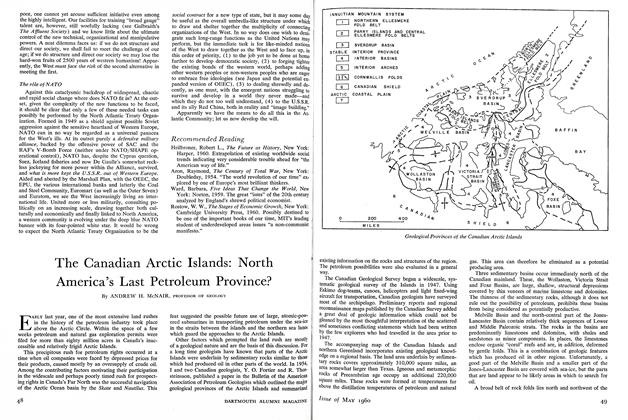

FeatureThe Canadian Arctic Islands: North America's Last Petroleum Province?

May 1960 By ANDREW H. McNAIR, -

Feature

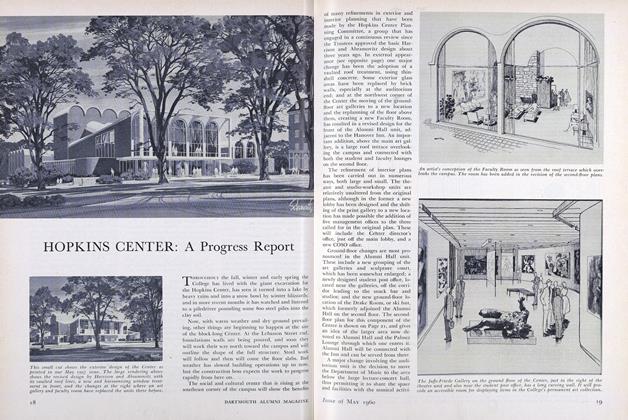

FeatureHOPKINS CENTER: A Progress Report

May 1960 -

Feature

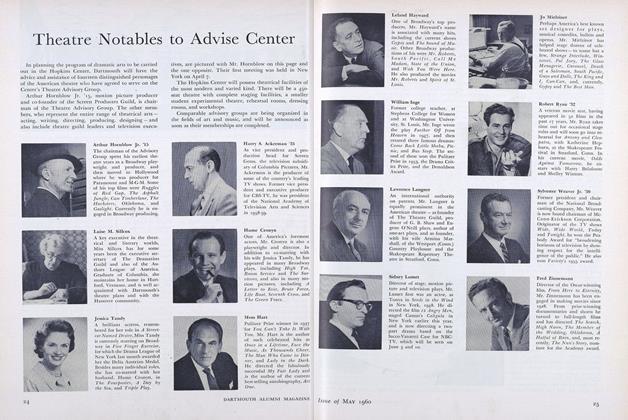

FeatureTheatre Notables to Advise Center

May 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1960 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

Features

-

Feature

FeatureExtracurriculn Vitae

January 1975 -

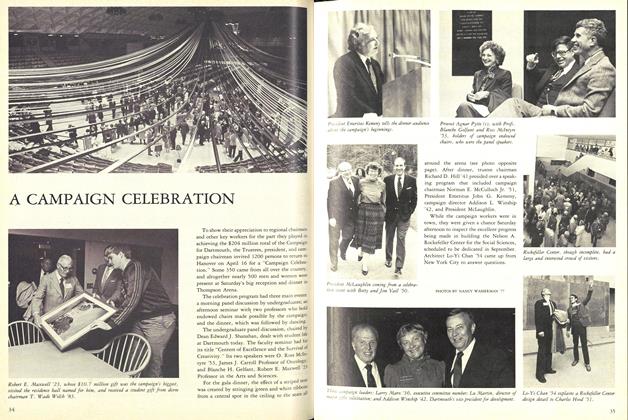

Cover Story

Cover StoryA CAMPAIGN CELEBRATION

MAY 1983 -

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

OCTOBER, 1908 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureTHE CREATIVE ARTS

May 1954 By IRWIN ED MAN -

Cover Story

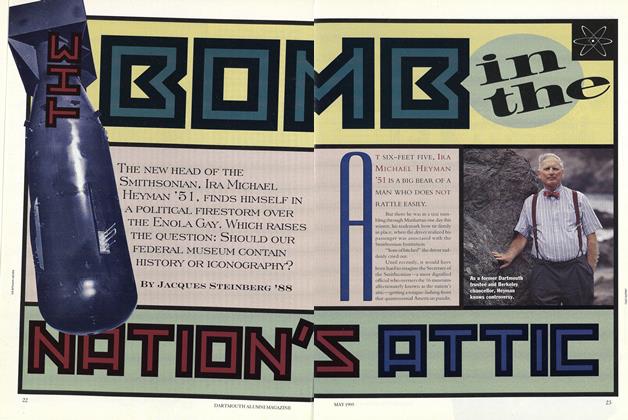

Cover StoryThe Bomb in the Nation's Attic

May 1995 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Feature

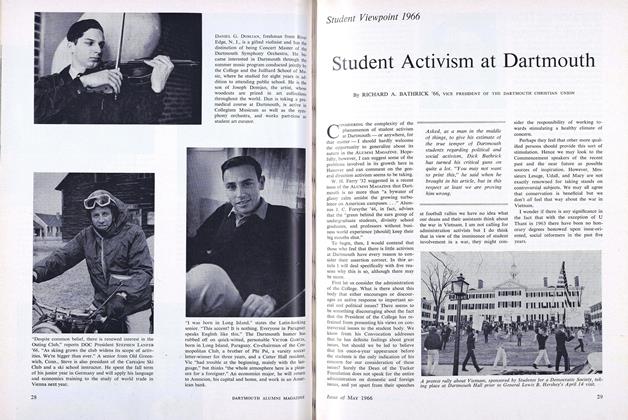

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

MAY 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66