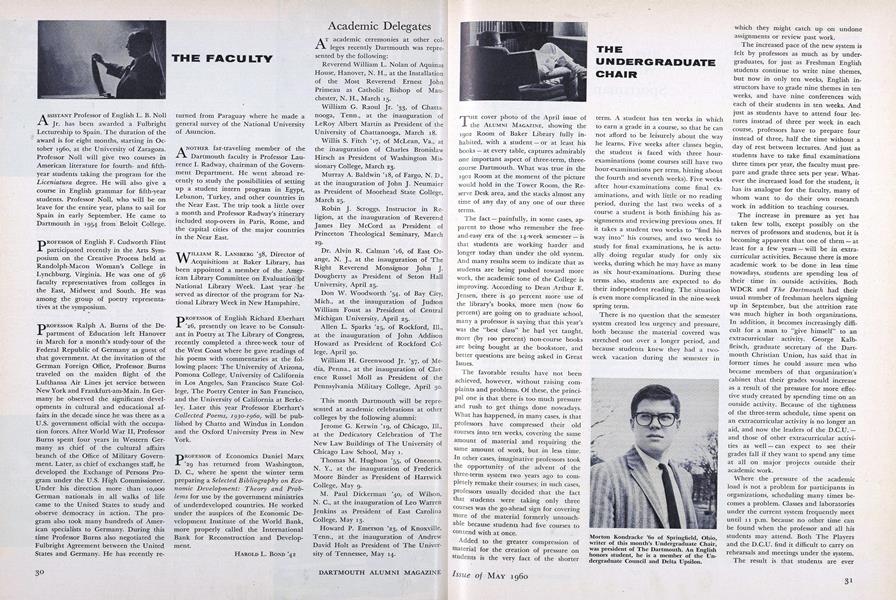

THE cover photo of the April issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, showing the 1902 Room of Baker Library fully inhabited, with a student — or at least his books - at every table, captures admirably one important aspect of three-term, three-course Dartmouth. What was true in the 1902 Room at the moment of the picture would hold in the Tower Room, the Reserve Desk area, and the stacks almost any time of any day of any one of our three terms.

The fact - painfully, in some cases, apparent to those who remember the free-and-easy era of the 14-week semester—is that students are working harder and longer today than under the old system. And many results seem to indicate that as students are being pushed toward more work, the academic tone of the College is improving. According to Dean Arthur E. Jensen, there is 40 percent more use of the library's books, more men (now 60 percent) are going on to graduate school, many a professor is saying that this year's was the "best class" he had yet taught, more (by 100 percent) non-course books are being bought at the bookstore, and better questions are being asked in Great Issues.

The favorable results have not been achieved, however, without raising complaints and problems. Of these, the principal one is that there is too much pressure and rush to get things done nowadays. What has happened, in many cases, is that professors have compressed their old courses into ten weeks, covering the same amount of material and requiring the same amount of work, but in less time. In other cases, imaginative professors took the opportunity of the advent of the three-term system two years ago to completely remake their courses; in such cases, professors usually decided that the fact that students were taking only three courses was the go-ahead sign for covering more of the material formerly untouchable because students had five courses to contend with at once.

Added to the greater compression of material for the creation of pressure on students is the very fact of the shorter term. A student has ten weeks in which to earn a grade in a course, so that he can not afford to be leisurely about the way he learns. Five weeks after classes begin, the student is faced with three hour-examinations (some courses still have two hour-examinations per term, hitting about the fourth and seventh weeks). Five weeks after hour-examinations come final examinations, and with little or no reading period, during the last two weeks of a course a student is both finishing his assignments and reviewing previous ones. If it takes a student two weeks to "find his way into" his courses, and two weeks to study for final examinations, he is actually doing regular study for only six weeks, during which he may have as many as six hour-examinations. During these terms also, students are expected to do their independent reading. The situation is even more complicated in the nine-week spring term.

There is no question that the semester system created less urgency and pressure, both because the material covered was stretched out over a longer period, and because students knew they had a two-week vacation during the semester in which they might catch up on undone assignments or review past work.

The increased pace of the new system is felt by professors as much as by undergraduates, for just as Freshman English students continue to write nine themes, but now in only ten weeks, English instructors have to grade nine themes in ten weeks, and have nine conferences with each of their students in ten weeks. And just as students have to attend four lectures instead of three per week in each course, professors have to prepare four instead of three, half the time without a day of rest between lectures. And just as students have to take final examinations three times per year, the faculty must prepare and grade three sets per year. Whatever the increased load for the student, it has its analogue for the faculty, many of whom want to do their own research work in addition to teaching courses.

The increase in pressure as yet has taken few tolls, except possibly on the nerves of professors and students, but it is becoming apparent that one of them - at least for a few years — will be in extracurricular activities. Because there is more academic work to be done in less time nowadays, students are spending less of their time in outside activities; Both WDCR and The Dartmouth had their usual number of freshman heelers signing up in September, but the attrition rate was much higher in both organizations. In addition, it becomes increasingly difficult for a man to "give himself" to an extracurricular activity. George Kalbfleisch, graduate secretary of the Dartmouth Christian Union, has said that in former times he could assure men who became members of that organization's cabinet that their grades would increase as a result of the pressure for more effective study created by spending time on an outside activity. Because of the tightness of the three-term schedule, time spent on an extracurricular activity is no longer an aid, and now the leaders of the D.C.U. and those of other extracurricular activities as well - can expect to see their grades fall if they want to spend any time at all on major projects outside their academic work.

Where the pressure of the academic load is not a problem for participants in organizations, scheduling many times becomes a problem. Classes and laboratories under the current system frequently meet until 11 p.m. because no other time can be found when the professor and all his students may attend. Both The Players and the D.C.U. find it difficult to carry on rehearsals and meetings under the system.

The result is that students are ever more frequently being faced with a choice between devoting themselves to study or extracurricular activities, and increasingly often underclassmen are turning away from the activities, and upperclassmen are finding it dangerous to commit themselves to a major extracurricular office. It is difficult to predict the end result of such a trend; it is possible that the major extracurricular organizations will continue to perform their necessary functions, but eliminate many of the extra project efforts they once took on.

There is one fact, however, which indicates that the current feeling of pressure on the student body, faculty, administration, and even extracurricular organizations, while perfectly valid now, is only temporary: what the College is going through now is a transitional stage in which problems have yet to be solved and an adjustment process has yet to be completed. Provost John W. Masland has said that while the essential framework of the new system is not to be tampered with, much is being done to clear up technicalities within the framework.

The administration, faced with three registration periods and three processings of grades per year, is seeking to ease its load by requiring students to plan their courses for a full year ahead. The proposal has met with much vociferous student opposition, but appears to be headed for practice beginning this year.

The faculty's pressures may be eased by a process, now being most successfully managed by the Mathematics Department, of arranging departmental calendars so that any one professor may take an overload of courses during one term and have another term free for research or leave.

The student-felt pressure may be alleviated rather naturally in the future: Dartmouth classes are becoming steadily better academically, steadily better able to handle the new three-term load, so that the pressure which many undergraduates now feel excessive may in the future be just enough to push students to their books and the academic spirit into their heads. It is possible, also, that these new students will find it easier to handle their academic work and improve extracurricular activities as well.

Serious students and faculty members are thus ready to take on the added pressure bearing upon them by virtue of the new system. The evidence everywhere is that Dartmouth is to be a more intellectually active institution, and it is apparent that the present hardships are, as it were, the birth pangs of a better Dartmouth.

Morton Kondracke '60 of Springfield, Ohio, writer of this month's Undergraduate Chair, was president of The Dartmouth. An English honors student, he is a member of the Undergraduate Council and Delta Upsilon.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Poetry of History: William Faulkner's Image of the South

May 1960 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR., -

Feature

Feature"What We Are After"

May 1960 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Feature

FeatureNATO in Trouble

May 1960 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31, -

Feature

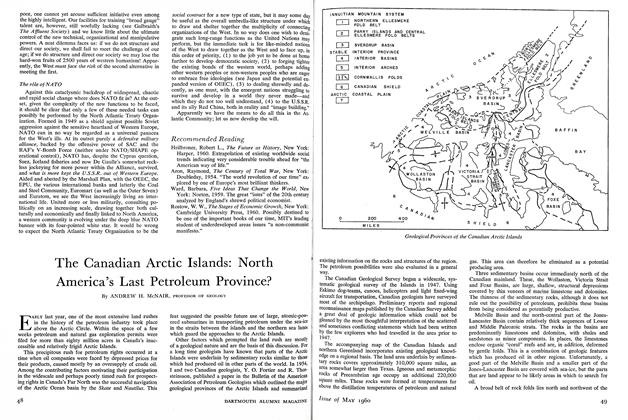

FeatureThe Canadian Arctic Islands: North America's Last Petroleum Province?

May 1960 By ANDREW H. McNAIR, -

Feature

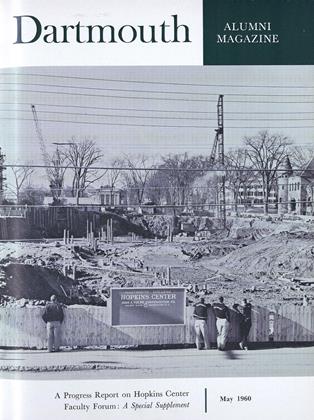

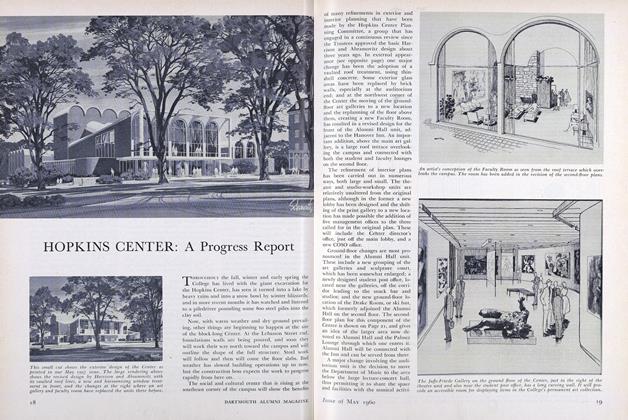

FeatureHOPKINS CENTER: A Progress Report

May 1960 -

Feature

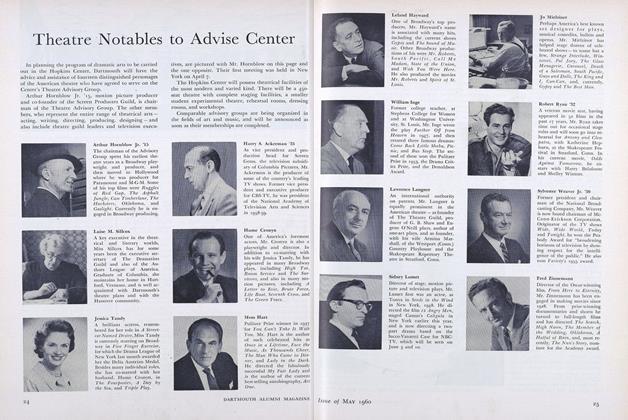

FeatureTheatre Notables to Advise Center

May 1960

MORTON M. KONDRACKE '60

Article

-

Article

ArticleFood for Thought

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards Conferred

MARCH 1968 -

Article

ArticleSafe

February 1977 -

Article

ArticleHopkins and a "Habit of Mind"

JANUARY 1959 By G. W. STONE JR. '30 -

Article

ArticleA Piece of My Soul

MAY 1997 By Jennifer Daniel '97 -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

JANUARY 1929 By Samson Occom