MY introduction to the "admissions problem" was early and abrupt. I think it came the afternoon of my first day on this job, November 1, 1945; at least I was still in that slightly embarrassing state of mind, familiar to all newcomers to any desk job, with both my mind and the "incoming" box pristinely empty, when my first "customer" walked into the office. It was that wonderful Dartmouth servant, the late Bob Strong, who had long been Director of Admissions and Dean of Freshmen.

Bob was holding in one hand an incoming letter and in the other an old felt "D." His opening words were: "You might as well know the worst now since there will be lots of it later."

As I am sure you have guessed, the letter was from an alumnus who felt and said in no uncertain words that he had no further use for his "D," or indeed for his college, after Bob had sent him the unhappy word that his son had not made it in that year's competition for admission.

I can still hear Bob patiently, but, for me, painfully explaining: "No, this was not something new, it was as old as the selective system ... there would surely be more of it as the competition stiffened... it was hard on friendships (as he and Mr. Hopkins had discovered and I would) but leaving aside the torn position of the College, the to-be-expected myopia of parents in these cases, the fact that such decisions are never better than the informed judgment of fallible men and, in the case of an alumni son, as here, after stretching the preference to the limit, there still was no ducking his obligation not to commit a crime against that boy."

"So," said Bob with his slightly puckish grin, "I choose to murder the presidents of this place!"

The crime against the boy, of course, is knowingly putting him up against a competition he is not, at least on the record, prepared to handle. It's a curious thing, but true, that most of us will slay anyone who mismatches our offspring in any other kind of endeavor but we find it almost impossible to apply the same common-sense con- cern for the youngster's welfare when it comes to what is called "getting into college."

I believe this attitude in large part is caused by our failure to get three things across:

(1) "Getting into college" is a good thing to achieve only if being admitted means that those who are best able to judge believe the boy is ready to handle the particular competition he must face from his future classmates, not on admission, but in the classroom for four hard years. If "getting in" does not mean this, it means worse than nothing because it means only an invitation to trouble, perhaps tragedy, for the boy and everyone who cares about him.

(2) Nobody, literally nobody, can make this judgment about the competition an applicant will face in a particular college, in a particular four-year period, as well as the admissions officers whose job it is to study the bulging files of the thousands of other applicants who will set the pace of that competition.

(3) Just as a fine mind will not take the place of strong, trained legs in the competition of a footrace, nothing can take the place of a prepared intellect as the basic qualification necessary for today's academic pace in our leading colleges. After, but only after, that basic qualification is met can other desirable personal qualities and distinctions make the difference as between applicants in this competition. This is the way it has always been in the selective process; what is changing each year as Dartmouth is more and more sought after is the level of that basic academic qualification below which, as Bob Strong put it to me, admission is a crime against the boy.

Difficult and personal as are these disappointments for all of us who live with them, they are only one aspect of the "admissions problem." The other side of the matter, and the one which the TPC study properly emphasized, is how to keep the College first rate in its own competition by attracting to it more candidates of truly outstanding qualifications.

And then in the middle (as always) of these two contending pulls is the on-going search of the College to find more exact, more sensitive ways to make judgments that will better serve both the thousands knocking at her gates and the high purposes which Dartmouth must serve if she is to be wanted as in the end we all want her to be wanted always.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureWHY a Hopkins Center at Dartmouth?

October 1961 -

Feature

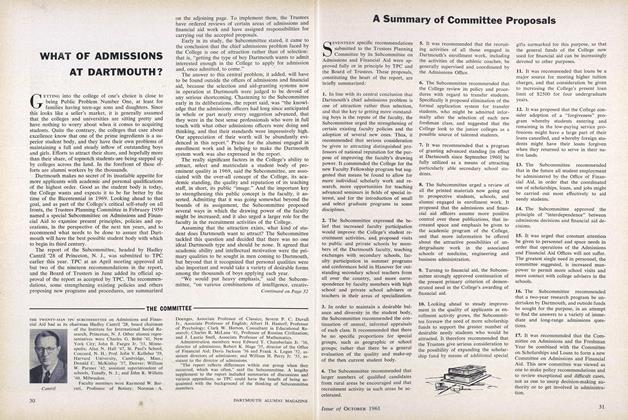

FeatureWHAT OF ADMISSIONS AT DARTMOUTH?

October 1961 -

Feature

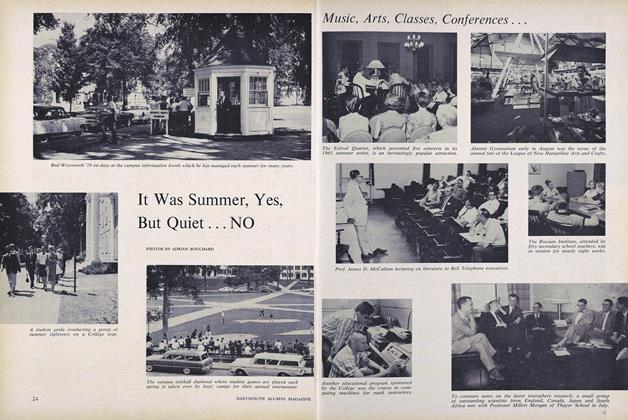

FeatureIt Was Summer, Yes, But Quiet... NO

October 1961 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1961 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY

Features

-

Feature

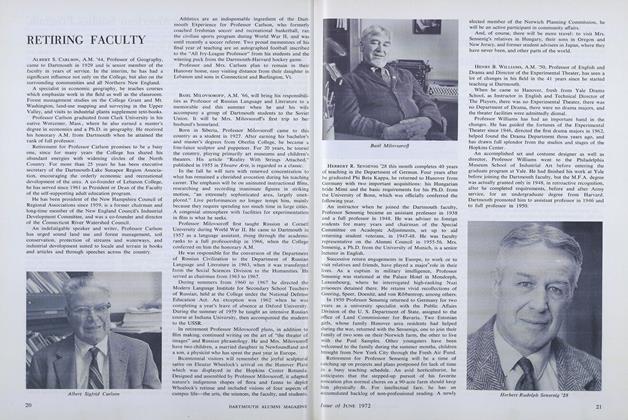

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1972 -

Feature

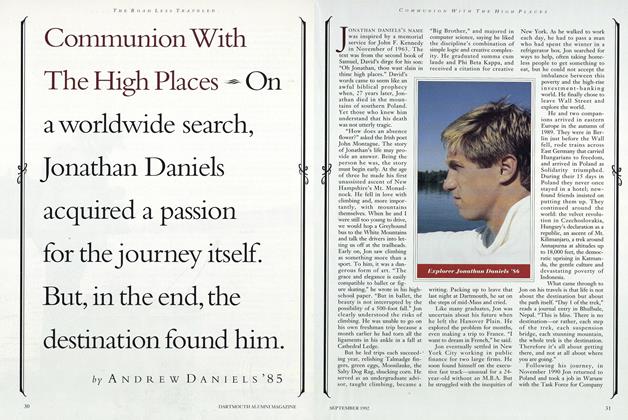

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Feature

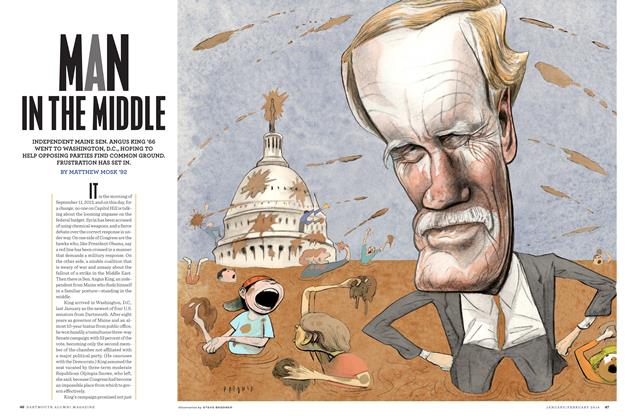

FeatureMan in the Middle

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

FEATURES

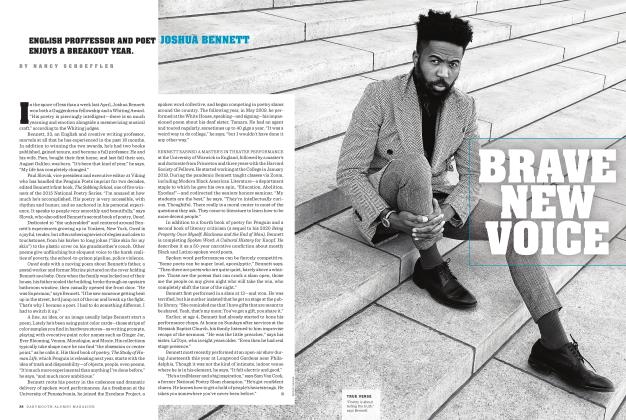

FEATURESBrave New Voice

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER -

Feature

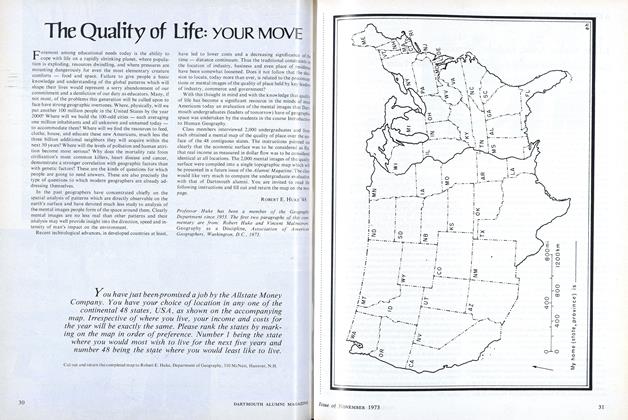

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

November 1973 By ROBERT E. HUKE'48 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow to Avoid Being Taken to the Cleaners by Your Ex

Sept/Oct 2001 By STACY D. PHILLIPS ’80