The following statement telling whyDartmouth attaches such significance tothe Hopkins Center was written by JohnL. Stewart, Professor of English, to beprinted and distributed among students,prospective students, and others interested in the creative arts center scheduledto open next fall. The editors have obtainedpermission to print it here, because they believe it will be of great interest to the alumni.

THE Hopkins Center at Dartmouth College, an integrated group of buildings named in honor of Ernest Martin Hopkins, who from 1916 until his retirement in 1945 served as the eleventh president of the College, is dedicated to the assumption that the creative and performing arts have a role in liberal education which warrants providing those who pursue them with the finest possible facilities. Designed by Wallace Harrison, the Center contains galleries and studios for painting, sculpture, and the graphic arts; metal and woodcraft workshops; two theatres, dressing rooms, stage shops, and full production equipment; auditoria, music rehearsal rooms for individuals and ensembles, broadcasting and recording instruments; and a number of social areas where students, faculty, alumni, and guests of the College can meet surrounded by the beauty of finished works of art and the excitement that is present wherever men, alone or in groups, are wrestling with colors, sounds, or words to create new works. A complete description of the facilities and uses of the Center could fill pages, for it is one of the largest and finest installations of its kind in the nation.

Why should Dartmouth College, a comparatively small institution somewhat removed from the urban foci of the arts, and one proposing to give her men a broad liberal education rather than thorough preprofessional training in any of the arts, crafts, or sciences, commit herself as deeply as she has in Hopkins Center? What does she hope such a commitment will do for her students? How does she define the place of the creative and performing arts in a college education —particularly in the education of those students who are not and do not expect to become either creators or performers?

There are those not unfriendly to the arts who profess doubts about any college's investing so much to support them. Such persons wonder, and with some good reason, if Americans generally are not trying to do too much for the arts, the artists, and their audiences. For many years artists were somewhat apart from the main body of our society and were often regarded with suspicion or downright hostility, which were not the less hurtful because they might be partially hidden beneath a pretense of respect and esteem. Consequently artists of all kinds tended to look for true understanding and appreciation among other artists and to develop a private language, almost a whole private culture, for artists only. Now a revolution has taken place, and the arts no longer belong to the very few but are widely accepted as a part of normal life. More and more college students sing, play instruments, act, paint and write with little thought of reward beyond the pleasure these activities give to themselves and their friends and classmates. In fact, so many are engaged in the arts and so much good will seems to be loosely floating around that some who complained for years about the neglect of the arts now worry lest they be smothered with kindness. This is not a perverse objection by inveterate malcontents.

Take creativity. From our first day at nursery school until our retirement in Florida we are urged to be creative. Well and good. Or apparently well and good. Yet in all the exclamations over some child who dipped his fingers in paint and smeared bright colors on a piece of paper twice as large as himself, or over a retired contractor who organized a music group to perform for the Sunshine Club, we may forget that significant creativity involves more than en- thusiasm, flashing colors, and new sounds in the land. Such activity is unquestionably delightful, and it can relieve boredom, release tension, salvage a disappointing day, and send one to bed full of satisfaction and sweet dreams. But unless there is more, much more, it should not in any serious sense be called art. In America we feel more than a little ashamed of our long neglect of the arts. As we try to make up for it, we run the risk of bestowing the title of "art" too freely, of giving encouragement and support to people who are not artists of any kind, not even to the extent of being good members of an audience. This is bad all around, and the surest way to destroy the arts is to forget or attempt to dispense with standards so that no tiny nugget of talent, no faint promise of possible ability, will be neglected. An arts center is not a glorified sandbox. The Hopkins Center is not established on the proposition that it is a Good Thing for college men to come in and paddle around with paints, toy with woodworking tools, and pass the time of day at the piano picking out one by one the notes of a new show tune.

What, then, is real creativity, and how does it advance the liberal education of any considerable number of men in a college such as Dartmouth? To answer we must go back a little way and say first what we expect a work of art to be. It is, first of all, an object of aesthetic delight; it is also a means of communication; and it is the enduring record of an insight into human experience, though this insight may be one which cannot be translated into words. The work of art has order, design, content. To bring it into being calls for the most scrupulous selection, interpretation, and arrangement. Though these processes may go on swiftly in what appears to be a random, even an accidental, order, though the creator may work much of the time without conscious deliberation, nevertheless, creativity makes an unlimited demand upon him for imagination, intelligence, perception, sympathy, taste, and the power of imposing unity on complex and rebellious materials.

One of the consequences of bringing such qualities to creating a picture, a statue, a piano sonata, a one-act play — yes, and a fine and carefully finished cabinet - is a heightened awareness and comprehension of the nature and value of many kinds of human experience. It is sometimes difficult at first for one who has had no experience with, say, composing to see that creating a string quartet leads to knowledge of anything other than how to compose another string quartet, especially since what music communicates has no verbal equivalent. Yet one who has created music - and one who has designed and built a beautiful piece of furniture - learns many things about the importance of balance, proportion, restraint, and responsible judgment, the threat of disorder and lawlessness, and the serenity that comes after mastery of a difficult problem in all human behavior as well as in art. Moreover, he learns it deeply: not just with his intellect, but his whole being, for his whole being was involved in his art.

But what of those who perform? What of the singers, instrumentalists, actors, directors, readers of poetry, and others who give sound and movement to the works of other men? Such recreators are not simply passive extensions of the artist's implements. For recreation is dynamic. It calls for patient study of the work of art to discover what it is - how its elements have been artistically ordered toward a unique whole that represents and interprets some facet of life. In different ways and other degrees, the qualities needed for creation are needed for recreation, and many of the lessons learned and many of the delights are the same.

Even the audience participates in the recreation. A play, for example, is not simply the action going on at any moment: it is the sum of all the actions of all the moments as they modify and qualify one another. The audience, too, must realize the ordered whole as did the playwright at the beginning and as did the director, the scene designer, and the actors who came after. But artistic quality and content can be fully apprehended only by those whose native sensitivity and capacity for imaginative response have been cultivated and whose artistic intelligence has been trained to perceive the conventions and internal relationships by which the beauty and meaning of a work of art are achieved. Sir Joshua Reynolds put this well in 1786 when he observed: "It is the lowest style only of arts, whether of painting, poetry, or music, that may be said, in the vulgar sense, to be naturally pleasing. The higher efforts of those arts, we know by experience, do not affect minds wholly uncultivated. This refined taste is the consequence of education and habit...."

Education and habit. What place is more suitable for encouraging these than a liberal arts college? Here the creator, the performer, the audience, the critic, the student, and the teacher can work together both in and out of the classroom to refine taste and give one another new insights. They can exchange their roles. They can keep each other up to the mark so that the arts, though means to the most intense enjoyment and superb avocations for the amateur, never degenerate into aimless play. And in a well-equipped art center they can do much that cannot be done elsewhere. They can cross quickly the boundaries between the arts; they can share in the ineffable stimulation that radiates through the halls wherever men are making new and beautiful things. Moreover, since creativity, recreation, intelligent audience response, and informed judgment of art exist not alone but as inseparable parts of a culture, an art center can - nay, must - draw upon the knowledge of many areas of learning, on literature, philosophy, anthropology, sociology, and history, to name but a few. "Art," Ernst Cassirer has written, "can embrace and pervade the whole sphere of human experience. Nothing in the physical or moral world, no natural thing and no human action, is by its nature and essence excluded from the realm of art, because nothing resists its formative and creative process." If this be so, then the Hopkins Center can use all the intellectual resources of the College, and it can repay those who provide them with new perspectives on their own special fields and interests. This is not just a center for the arts; it is, properly, a center for all learning.

Because of this, the conceptions and standards of understanding and discrimination, of independence, hard work, and originality to which the College is committed will not simply prevail, they will be strengthened by whatever strengthens the creative and performing arts, encourages the artists, and makes their work more readily available to the community of scholars and teachers. All who share in the activities of the Center, though their share be modest, will be wiser, happier, more responsible men and women.

That is why the Hopkins Center belongs at Dartmouth and bears the name it so proudly does.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT OF ADMISSIONS AT DARTMOUTH?

October 1961 -

Feature

FeatureADMISSIONS – As Seen at the President's Desk

October 1961 By J.S.D. -

Feature

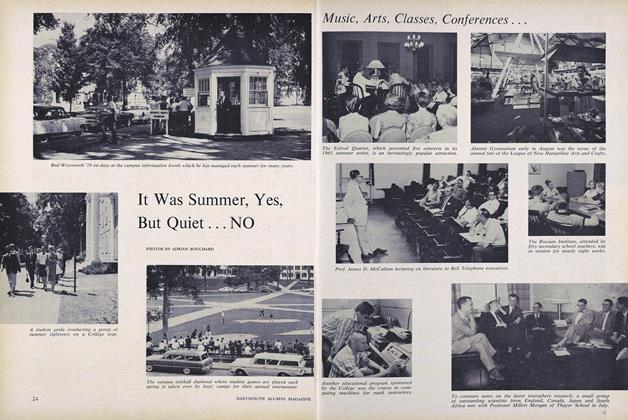

FeatureIt Was Summer, Yes, But Quiet... NO

October 1961 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1961 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY

Features

-

Feature

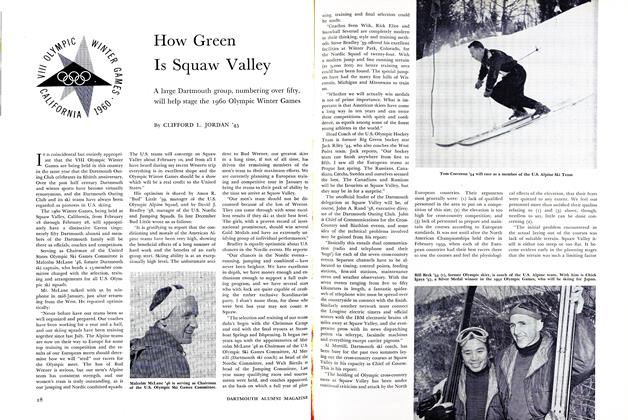

FeatureHow Green Is Squaw Valley

February 1960 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

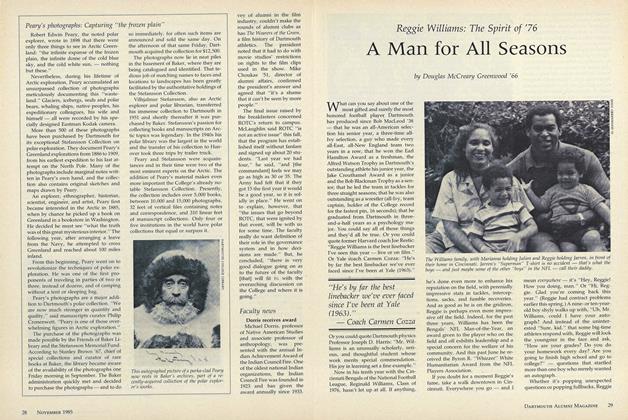

Cover StoryA Man for All Seasons

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Douglas McCreary Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureMinimum Standards

APRIL • 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

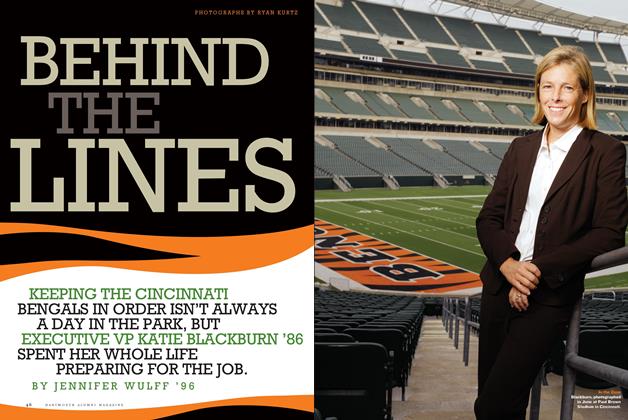

FeatureBehind the Lines

Sept/Oct 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureA Look Backward and A Look Ahead

JULY 1964 By MICHAEL JAY LANDAY '64 -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham