NEW HAMPSHIRE PROFESSOR OF CHEMISTRY, EMERITUS

IT gives me great pleasure to bring greetings and congratulations to the Class of 1960 from the Class of 1910, and to tell you about the College of our time. Our two groups have something in common. In the first place, each had the largest enrollment of its generation; 1960 with 805 entering freshmen was the largest class to enter Dartmouth up to last fall; 1910 came to Hanover 355 strong, a figure not exceeded during our stay in college. Both classes taxed the dormitory facilities. To take care of the extra men of 1960, the College reconstructed old South Hall, once known as the Commercial Hotel. The overflow 1910 freshmen were housed in Hallgarten, known as Hellgate, still standing behind Topliff Hall; in the Tavern Block on Main Street; and in New Hubbard, a wooden building erected in six weeks on a site now occupied by the rear end of Parkhurst Hall.

In the second place, both classes have proved that good athletes can also be excellent students. The varsity players of 1960 have shown that there is a close correlation between high grades and success on the football field. 1910 had three men who won both their D's and their Phi Beta Kappa keys. They were: Walter Norton, captain of the baseball team; Herbert Wolff, four-year letter winner on the tennis team; and little Sturgis Pishon, known to us as Spuddy. The last-named was about five feet five and he weighed about 130 pounds. He finally convinced the coaches that he was big enough to play quarterback on the varsity football team, and he showed his spunk in his first big game at the Polo Grounds in New York in 1908 when we beat Princeton 10 to 6. He threw the touchdown pass to Dutch Schildmiller '09, Ail-American end; and he also made a game-saving tackle in the last period. One of the fast Princeton backs had broken through our line and suddenly was at midfield with two burly blockers ahead of him. Pishon, in his deep safety position, was the only man between this trio and the goal line. There seemed no hope of stopping the runner, but somehow Spuddy threw his small body between the two blockers and brought down his man, thereby ending the last Princeton threat. Sturgis Pishon died in France during World War I in the crash of a training plane.

No account of our student athletes is complete without a mention of the late Clarke Tobin, All-American guard in his junior year. During his undergraduate days Clarke developed a talent for public speaking, and he won the Barge Medal for an original oration in his senior year. But his most notable accomplishment was as a student leader, always in the right direction. One warm March day in 1910, when at long last the snow on Main Street had begun to melt, someone threw a snowball and soon a real battle developed with imminent danger to store windows and pedestrians. Hanover's oneman police force soon appeared and he arrested the nearest culprit. The mob followed the pair to the jail on Allen Street; and soon they began to break windows and to threaten to rescue the prisoner from the arms of the law. Suddenly Clarke Tobin appeared on the steps of the police station, raised his arms and told the students how childishly they were behaving. Sheepishly and rapidly they dispersed, all because of the example of a leader who showed courage and sense.

The College of our time was quite different from the modern Dartmouth. The undergraduate body numbered between 1000 and 1200, and there were only sixty faculty members to teach us. Our tuition was $125 a year, $500 for the full four-year course; and some of this could be covered by scholarship aid. Then as now, this fee amounted to only half of the

cost of our instruction; so one can estimate that we owed the College about $150,000 when we were graduated. We started paying off this indebtedness in our senior year when we were solicited for money to build a new gymnasium to replace the one in Bissell Hall, then our only facility for indoor athletics and exercise. Up to this year the Class of 1910 has given Dartmouth about $360,000, so even with the depreciated dollar, our debt has been cancelled; but like all loyal alumni, we expect to continue to contribute, via the Alumni Fund and bequests, until the last Tenner has passed on.

Room rent in college dormitories averaged well below $100 per year, and board could be obtained in private eating clubs at from $3 to $3.50 per week. The College Dining Association, or Commons, in what is now the ballroom of College Hall, offered combination breakfasts at 15 cents, lunch for so cents, and dinner at 20 or 25 cents.

We were fortunate to have lived under our beloved Prexy, William Jewett Tucker, because poor health forced him to become inactive after our freshman year. Never to be forgotten were Dr. Tucker's chapel talks at the Sunday vesper services. When he finished a sermon, the silence in Rollins was complete; then everyone sang the closing hymn with spirit, feeling that he had received personal advice from a great and good man. Who can forget our Dean, Charles "Chuck" Emerson, who also served as the Director of Admissions; and the first Registrar of the College, Howard "Skeet" Tibbetts, 1900, feared but respected by all. The Secretary of the College was a young graduate named Ernest Martin Hopkins.

At the present time our living members number slightly more than one-half of all those once enrolled in the class; this in spite of casualties suffered in both World Wars. In scientific terms our period of half-life is fifty years, but fortunately 1910 is not like a radioactive element, or our rate of decay would be such that one-quarter of us would be alive fifty years from now. But if the Class of i960 has a similar half-life, there will be 400 of you alive in the year 2010 when you return tor your 50th reunion.

We have lost half of our athletes and half of our Phi Betes, so no case can be proved against strenuous physical activity or hard study. From our statistics one could draw the conclusion that longevity depends upon being named Smith and playing tennis. This non-scientific deduction is based on the fact that all of the five Smiths who entered college with us are still alive, and so are the four men who won their letters on the varsity tennis team.

1910 was probably an average class in undergraduate days, but we won one great distinction - we were the only class in our time to triumph twice in the fall football rush, in both our freshman and sophomore years. In this contest, held after dark, the two classes lined up on opposite ends of the campus, the football captain kicked a ball high in the air in the center, and the two groups rushed toward each other. Whoever reached the football first became the center of a milling, pushing mass, thinned only slightly by the individual fights that occurred on the periphery. After a time a pistol shot ended the struggle, and Palaeopitus decided the winner by finding out who held the ball. In our two rushes Tenners had possession of the trophy at the end.

The postgraduate honors that have come to my classmates are many. There is time to tell only about the three men who received honorary degrees from Dartmouth. The late Ben Ames Williams, awarded the Doctorate of Letters, was perhaps the best-known and most prolific of all Dartmouth authors. His stories of life in Maine, and his historical novels of the old South brought him his fame. Dr. Frank Meleney received the Doctorate of Science for his discovery of the antibiotic which he named Bacitracin. His long medical career, first in China and then at Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons, was not ended by retirement. He now practices surgery in Miami, Florida, and he is active in the medical school of Miami University.

The Rev. William Moe received the degree of Doctor of Divinity for his long and successful career in the ministry, particularly during his pastorate in Guilford, Connecticut. Bill once made the pages of the Saturday Evening Post for his work with the men in the county jail. He came to us from Bangor Theological Seminary in his junior year, and he graduated with us with salutatory rank. Ten years older than any of us, Bill had the distinction of being one of two married undergraduates. He is still active in his work with the inmates of the prison and the patients of a hospital near his Tolland, Conn., home; and his visits to these institutions are the high spots in the drab lives of many poor souls.

No group of young men like those in the Class of 1960 cares about receiving advice from oldsters, and I am not going to give you any. Without any suggestions from us, you seniors will, as alumni, be loyal to Dartmouth - her future depends on you, and you can help to make her the best college in the land. We can only hope that you will enjoy the next fifty years as much as we have enjoyed the time since we were graduated. Just try to keep young in spirit; then you will find that growing old can be fun. As George Bernard Shaw once wrote, "There is only one way to defy Time; and that is to have young ideas which may always be trusted to find youthful and vivid expression."

Professor Emeritus Andrew J. Scarlett '10

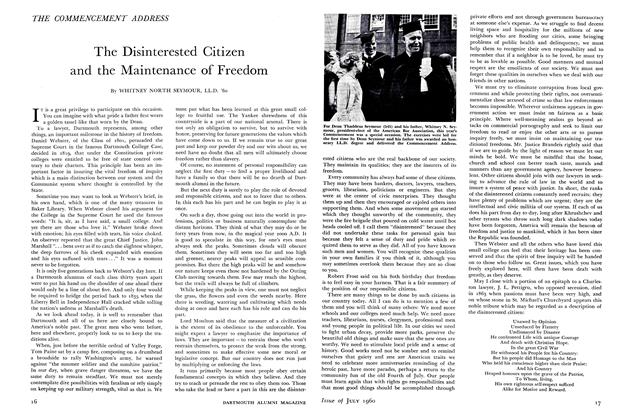

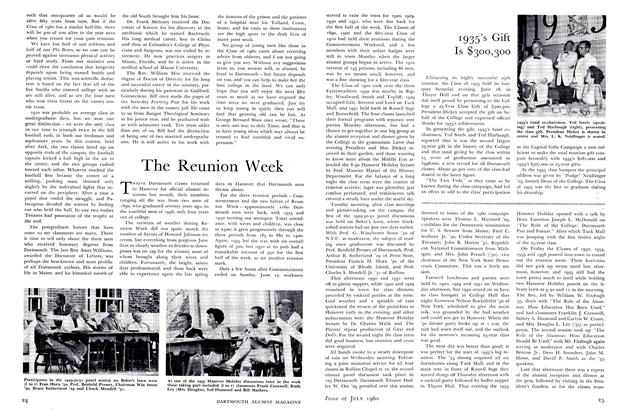

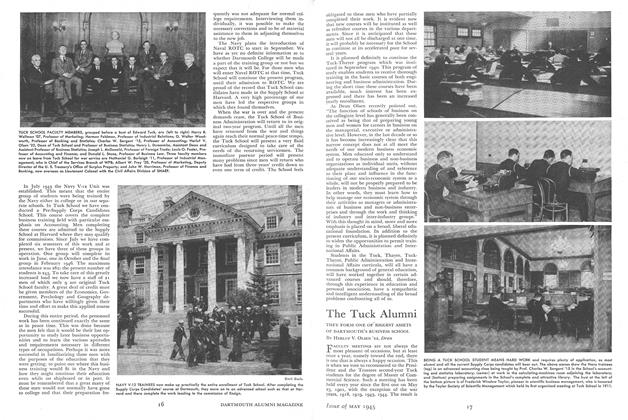

Participants in the 1929-30-31 panel session on Baker's lawn were (l to r) Fran Horn '30, Prof. Benfield Pressey, Chairman Win Stone '30, Bruce Sutherland '29 and Chuck Mendell '31.

At one of the 1935 Hanover Holiday discussions later in the week those taking part included (1 to r) classmates Frank Cornwell, Ruth Ley (Mrs. Douglas), Syd Diamond and Bill Mathers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Disinterested Citizen and the Maintenance of Freedom

July 1960 By WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, LL.D. '60 -

Feature

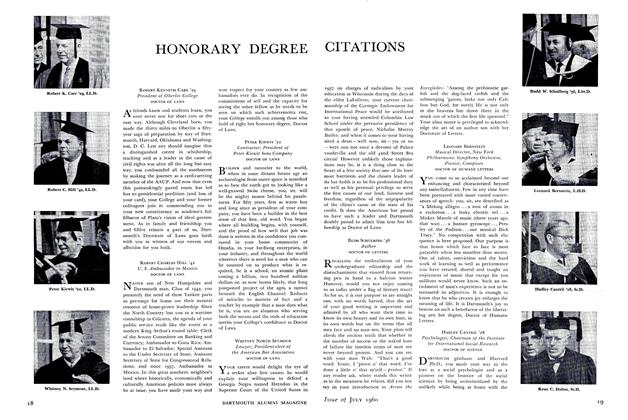

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1960 -

Feature

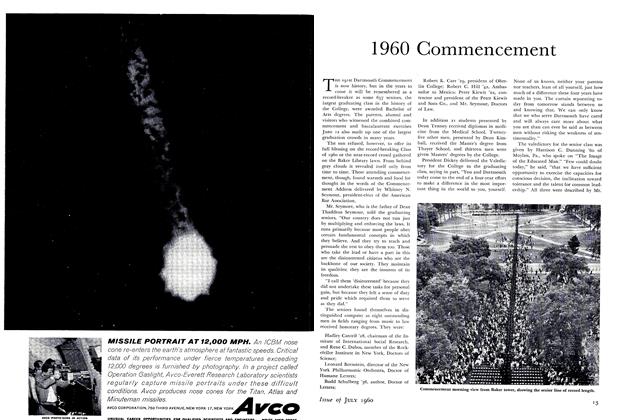

Feature1960 Commencement

July 1960 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureThe Image of the Educated Man

July 1960 By HARRISON CASE DUNNING '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1960 -

Feature

FeatureFor Distinguished Service ...

July 1960

ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JUNE 1977 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

June 1979 -

Books

BooksTHE THEORY OR RESONANCE AND ITS APPLICATIONS TO ORGANIC CHEMISTRY

May 1945 By Andrew J. Scarlett '10 -

Article

ArticleOxford

January 1946 By Andrew J. Scarlett '10 -

Article

ArticleBiarritz

January 1946 By Andrew J. Scarlett '10

Features

-

Feature

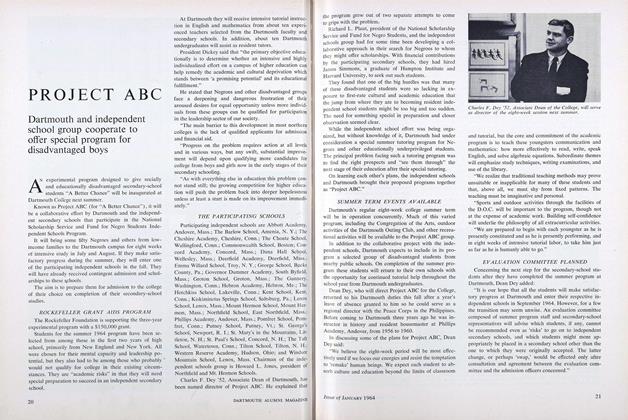

FeaturePROJECT ABC

JANUARY 1964 -

Feature

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Cover Story

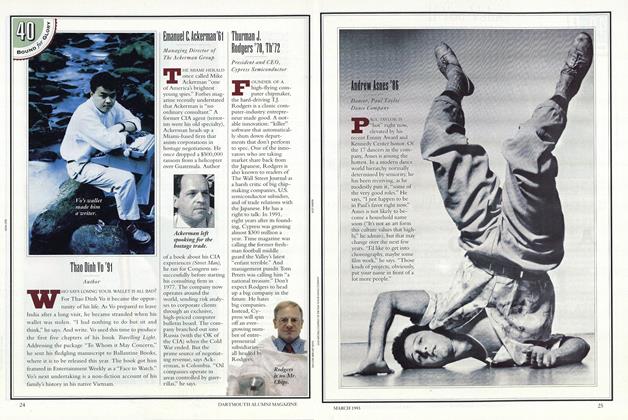

Cover StoryEmanuel C. Ackerman '61

March 1993 -

Feature

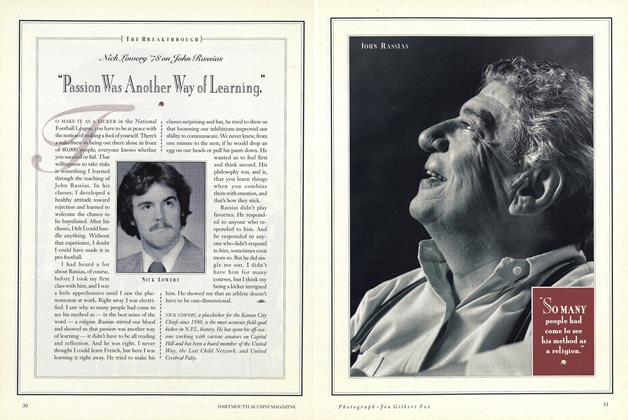

FeatureNick Lowery '78 John Rassias

NOVEMBER 1991 By John Rassias -

Feature

FeatureTHREE POEMS

January 1958 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

OCTOBER 1985 By Priscilla Sears