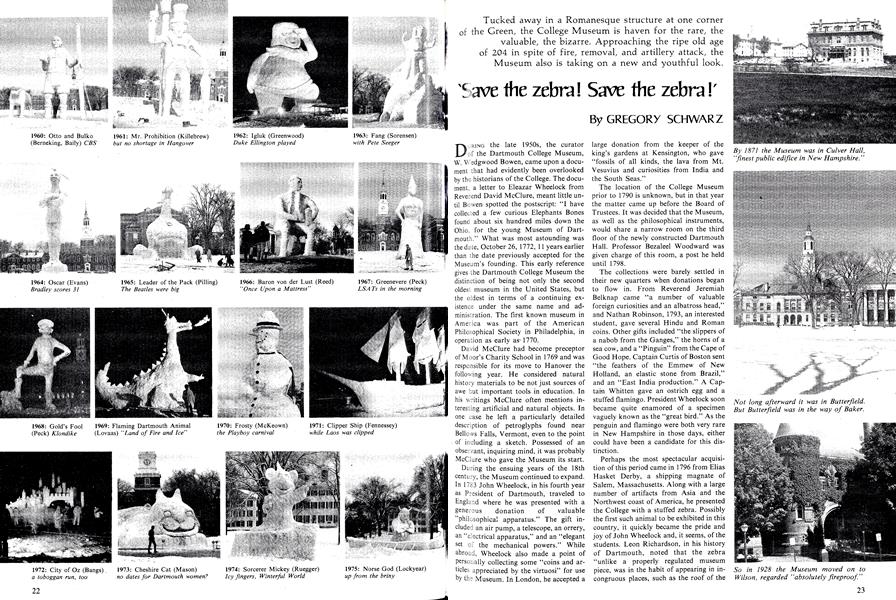

Tucked away in a Romanesque structure at one corner of the Green, the College Museum is haven for the rare, the valuable, the bizarre. Approaching the ripe old age of 204 in spite of fire, removal, and artillery attack, the Museum also is taking on a new and youthful look.

DURING the late 1950s, the curator of the Dartmouth College Museum, W. Wedgwood Bowen, came upon a document that had evidently been overlooked by the historians of the College. The document, a letter to Eleazar Wheelock from Reverend David McClure, meant little until Bowen spotted the postscript: "I have found about six hundred miles down the Ohio, for the young Museum of Dartmouth." What was most astounding was the date, October 26, 1772, 11 years earlier than the date previously accepted for the Museum's founding. This early reference gives the Dartmouth College Museum the distinction of being not only the second oldest museum in the United States, but the oldest in terms of a continuing existence under the same name and administration. The first known museum in America was part of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, in operation as early as 1770.

David McClure had become preceptor of Moor's Charity School in 1769 and was responsible for its move to Hanover the following year. He considered natural history materials to be not just sources of awe but important tools in education. In his writings McClure often mentions interesting artificial and natural objects. In one case he left a particularly detailed description of petroglyphs found near Bellows Falls, Vermont, even to the point of including a sketch. Possessed of an observant, inquiring mind, it was probably McClure who gave the Museum its start.

During the ensuing years of the 18th century, the Museum continued to expand. In 1783 John Wheelock, in his fourth year as President of Dartmouth, traveled to England where he was presented with a generous donation of valuable "philosophical apparatus." The gift included an air pump, a telescope, an orrery, an "electrical apparatus," and an "elegant set of the mechanical powers." While abroad, Wheelock also made a point of personally collecting some "coins and articles appreciated by the virtuosi" for use by the Museum. In London, he accepted a large donation from the keeper of the king's gardens at Kensington, who gave "fossils of all kinds, the lava from Mt. Vesuvius and curiosities from India and the South Seas."

The location of the College Museum prior to 1790 is unknown, but in that year the matter came up before the Board of Trustees. It was decided that the Museum, as well as the philosophical instruments, would share a narrow room on the third floor of the newly constructed Dartmouth Hall. Professor Bezaleel Woodward was given charge of this room, a post he held until 1798.

The collections were barely settled in their new quarters when donations began to flow in. From Reverend Jeremiah Belknap came "a number of valuable foreign curiosities and an albatross head," and Nathan Robinson, 1793, an interested student, gave several Hindu and Roman coins. Other gifts included "the slippers of a nabob from the Ganges," the horns of a sea cow, and a "Pinguin" from the Cape of Good Hope. Captain Curtis of Boston sent "the feathers of the Emmew of New Holland, an elastic stone from Brazil," and an "East India production." A Captain Whitten gave an ostrich egg and a stuffed flamingo. President Wheelock soon became quite enamored of a specimen vaguely known as the "great bird." As the penguin and flamingo were both very rare in New Hampshire in those days, either could have been a candidate for this distinction.

Perhaps the most spectacular acquisition of this period came in 1796 from Elias Hasket Derby, a shipping magnate of Salem, Massachusetts. Along with a large number of artifacts from Asia and the Northwest coast of America, he presented the College with a stuffed zebra. Possibly the first such animal to be exhibited in this country, it quickly became the pride and joy of John Wheelock and, it seems, of the students. Leon Richardson, in his history of Dartmouth, noted that the zebra "unlike a properly regulated museum piece, was in the habit of appearing in incongruous places, such as the roof of the chapel or the belfry of the College, thus requiring laborious transportation back to its normal abode."

Just how highly the President prized the animal is evidenced by his reaction to the fire of 1798. When flames broke out on the second floor of Dartmouth Hall, everyone turned out to battle the blaze. The actions of some of the faculty amused the students so much that stories about them were handed down for many years thereafter. It seems that while Professor John Smith was imploring the men to protect the library, Professor Woodward was calling for the rescue of the air pump and at the same time Wheelock was shouting, "Save the zebra! Save the zebra!" To the relief of all, though the Museum was only slightly damaged, the zebra and the "great bird" survived intact.

The first known catalogue of the collections was made about 1810. Among the items listed were "a piece of the stone that fell in Connecticut [from the meteor shower at Weston, Connecticut, in 1807]; the knife with which Josiah Burnham murdered the honorable Rupell Freeman and Mr. Starkweather [this incident occurred in Haverhill, New Hampshire, in 1806]; two fragments of the Bastille; petrified wine taken from the ruins of the Herculaneum; an instrument plowed up in Chesterfield, New Hampshire, and even "a piece of the Rock of Gibraltar." American Indian culture was not forgotten, as there "were "a sachem's cap; an Indian pillow; the headdress of an Indian chief; and an Indian Lady's indispensable." Several coins as well as a large number of geological specimens were also mentioned. Of the over 400 items listed, only about 15 are still identifiable as being in the collections today; alas, neither the murder weapon nor the "indispensable" is among them.

It was in 1811 that the first major "renovation" of the Museum was undertaken. The Museum room was situated in such a manner that in order to get from classrooms at one end of the third floor to those on the other, faculty and students first had to descend to the second floor and then go up again on the other side. Incensed at what they considered a needless expenditure of energy, several students decided that the time had come to remedy the situation. Procuring a small but serviceable cannon, they dragged it to the third floor, loaded it, and proceeded to blow down the walls of the Museum. The perpetrators of the assault were expelled, but for at least one of the culprits things turned out fine. Evidently discovering his life's calling during the incident, he enlisted in the Army, entered an artillery unit, and later on became a general.

The worst result of the attack did not come from the bombardment but from the decision of the administration to pack up the collections and store them in the attic. Perhaps it was meant to be only temporary, but with the advent of the War of 1812 and the strife of the Dartmouth College Case, the Museum remained in storage virtually forgotten for the next 16 years.

The cannon itself was no doubt confiscated and probably packed away as well. A small bronze cannon, without data, is still in the Museum collections, and in all probability this is the one that was used that day. Though the zebra is also known to have weathered this second near-disaster, it is here that we lose track of it.

The collections gathered dust until Benjamin Hale, professor of chemistry and mineralogy, unearthed them in 1827. Setting up a small exhibition room in the medical building, he ambitiously undertook to expand the collections whenever possible and in a few years was said to have amassed over 2,300 specimens. A new catalogue of the geological section was drawn up, but of the 1,800 items listed only about 30 can now be found. In 1829 the Museum was again placed in Dartmouth Hall, though understandably not in the same place as before the cannon incident.

In 1838 Frederick Hall, Class of 1803, and one time inspector of the Museum (1804-5), gave a very large collection of geological specimens as well as a few anthropological items. The "cabinet," as such collections were called, numbered over 5,000 specimens and was valued at over $5,000. Hall's gift also included funds of $5,000; a chip from the keel of Captain Cook's ship; a canoe model from Ceylon made entirely of cloves; mosaic fragments from Adrian's villa near Rome and a brick from "the famous city of Astalan"; and, according to the Museum records, a piece of mahogany from George Washington's coffin. Hall's tastes knew few bounds.

Space in Dartmouth Hall proved too small for all this largesse and in 1840 the Museum was transferred to a new home in the newly completed Reed Hall, where it occupied the southwest corner of the first floor. During its 31 years there, only three donations of note seem to have been received, the most important being a set of Assyrian bas reliefs. These large stone carvings were the second such set to come to this country. Originally assembled in Reed Hall upon their arrival, they were moved several times, with the set eventually being split up between Carpenter Hall and Wilson Hall. Early last year the reliefs in Wilson were reunited with the others in a room in the refurbished Carpenter galleries. The only other large donations were 400 shells from Dr. William Prescott and a substantial number of mounted birds given by Henry Fairbanks, professor of natural history.

As the study of natural history was growing, the Museum again needed to expand, and when Culver Hall was in the planning stage a large space was designated for the collections. Culver was completed in 1871 and stood across the street from the present Topliff Hall. The geological section occupied a spacious room on the top floor, the mounted animals a smaller room on the floor below.

For the rest of the 19th century, the Museum increased its holdings, especially in anthropology. A historically significant collection of American Indian artifacts was donated by Mrs. William Leeds from a collection her late husband had acquired while he was employed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington. In 1879, when Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce came to the capital, Leeds was assigned to show him around the city. A few months later, Leeds left his job and evidently took with him some of the gifts that Chief Joseph had brought with him from the reservation. These articles are now in the Museum, including a chiefs costume mounted on a mannequin made to resemble Joseph.

An important phase in the Museum's history occurred in 1893 when the College received a bequest of $141,000 from the estate of Ralph Butterfield, 1839. His instructions designated that the money be used for the foundation of a professorship in paleontology, archaeology, ethnology and kindred subjects, and for the erection of a suitable building to house the Museum. Ralph Butterfield had been interested in mineralogy as a student and though he went on to practice medicine as well as dabble in real estate, he retained his early interest. Construction of Butterfield Hall, as the building was named, began in 1895 and was completed the following year. The Museum occupied the entire third floor of the structure, with the other two floors being devoted to classrooms.

Throughout the first two decades of this century more ethnological material came in. Ainu, Japanese, and Korean artifacts were presented by Dr. James H. Pettee, 1873, and when Professor William Patten traveled to New Guinea he returned with many interesting things for the Museum. One of the larger collections came from Mrs. Hiram Hitchcock, wife of the former Museum curator, who donated 456 pieces of the Cesnola Collection of Cypriot antiquities. These artifacts were once part of the 35,000 specimens uncovered in Cyprus by Luigi di Cesnola, the United States Consul.

When Baker Library was being planned, the site selected was directly behind Butterfield Hall. It was decided that the Museum building no longer fit in with the architectural scheme of the campus and should be demolished. So, with the completion of Baker in 1928, Wilson Hall, the old library building, was renovated to serve the purposes of the Museum. The transferral of the collections to Wilson marked an important step in the functioning of the Museum. Previously, the collections were all at least partially controlled by the various departments concerned, but after the move the Dartmouth College Museum assumed complete control of the specimens and a far more efficient system of caring for the objects.

Though progressing slowly at first, the exhibit program advanced rapidly after 1935 under the direction of the new curator, W. Wedgwood Bowen. The collections were reorganized and many new displays erected. Accessions also increased with several very large donations, the largest and most valuable given by the late Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill. Col. Churchill had served as inspector of Indian schools for the Department of the Interior from 1899-1908. His job gave him the opportunity to visit every tribe in the United States and territories. Mrs. Churchill accompanied her husband and at each stop she obtained a few choice artifacts of local manufacture. Fortunately, she made it a point of avoiding tourist curios and, moreover, kept a detailed record of essential information about every purchase. The Churchills' gift now forms an important part of the Museum's holdings in American Indian artifacts, especially for the area of the Southwest.

Another notable donation of this period came from the late John Barrett, once United States Consul to Siam (1894-7). His large collection of Siamese objects includes a 600-year-old executioner's sword, reputed to have severed 300 heads. Much needed archaeological material from Central and South America was added by Victor M. Cutter '03 and Lt. Col. Charles L. Youmans '20.

About two years ago the College administration came to a decision about the fate of the Museum. Since the Geology Department possessed its own collection for study and no longer made use of the specimens stored in Wilson, it was judged that this area of the Museum was no longer functional within the framework of the College and should be disposed of. The exact method of disposition remained undecided until Robert Chaffee, director of the Museum, offered a solution. He had succeeded in gathering enough public support to establish a new museum focusing on natural history. The College found this agreeable and the Montshire Museum of Science soon became a reality. Now located on Route 10, just north of Hanover, this institution will serve as a regional museum for the natural history of Vermont and New Hampshire. From this point on the Dartmouth College Museum will consist only of the anthropological and historical sections. The dismantling of the natural history exhibits and their removal to the Montshire building were begun last spring and completed by October.

Renovation of Wilson Hall to better suit the new arrangement was started late last summer and continues at the present time. New facilities include a spacious laboratory, a new classroom, a computer terminal, and a darkroom. The first floor will consist of two large exhibit galleries. The former "bird room," once lined with cases of mounted birds, has been expanded and refurbished. The mounted animal heads which formerly greeted visitors entering the main lobby have also made the trip to the Montshire Museum. A large room previously packed with storage cases has been cleared out and will be used by students involved in Museum projects.

For the present, the second floor has remained basically intact, though renovation here is scheduled to begin after July. Future plans call for expanded work space and opening up new exhibit areas, one of which will be devoted to the Museum's growing costume collection.

Along with the remodeling, there have been several changes in the staff. Chaffee, curator of geology since 1948 and director 1968, has departed to become director of the Montshire Museum. Alfred F. Whiting, curator of anthropology for 18 years, retired in 1974 and is now at the Museum of Northern Arizona pursuing his interest in the ethnobotony of the Southwest. The position vacated by Whiting has been filled by Tamara Northern, a specialist in African art. Overall supervision of the Museum now falls to the director of Dartmouth College Galleries and Collections, a new post encompassing the Museum and the Hopkins Center and Carpenter Hall galleries. This position was filled in late 1974 by Jan van der Marck, a native of the Netherlands who came to the United States in 1961 and has served as chief curator of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

With an expanded budget and more and better facilities many of the problems that plagued the Museum in the past will be overcome - barring another student artillery assault. The cannon from the 1811 "renovation" is being placed in a permanent main-floor exhibit on the history of the Museum. Should some of the alumni have any old photographs of the Museum or information concerning its history - such as the fate of the zebra - the staff would appreciate hearing from you.

By 1871 the Museum was in Culver Hall,"finest public edifice in New Hampshire."

Not long afterward it was in Butterfield.But Butterfield was in the way of Baker.

So in 1928 the Museum moved on toWilson, regarded "absolutely fireproof."

New Hampshire schoolgirl meets Egyptianmummy in the Museum's collection.

Assistant Curator of the College Museum,Gregory Schwarz also wrote "Believe It orNot!" in the October 1974 issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

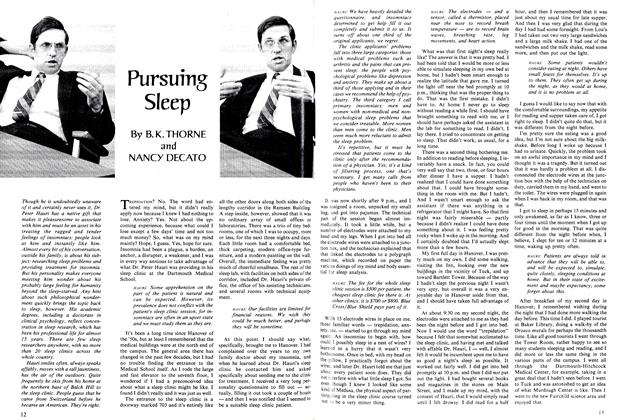

FeaturePursuing Sleep

February 1976 By B.K. THORNE, NANCY DECATO -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

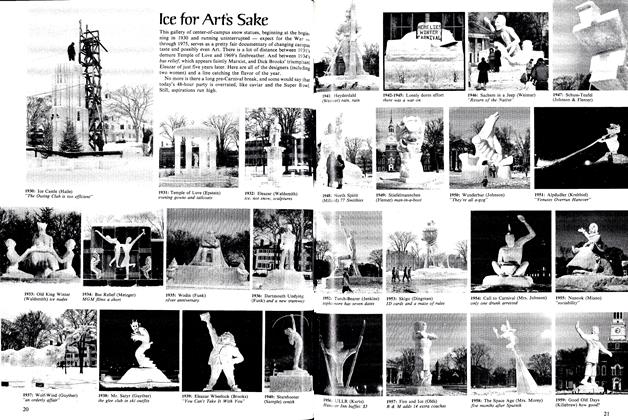

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Article

ArticleWinter Games

February 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

February 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

February 1976 By JOSEPH R. BOLDT JR., EVERETT P. HOKANSON

Features

-

FEATURE

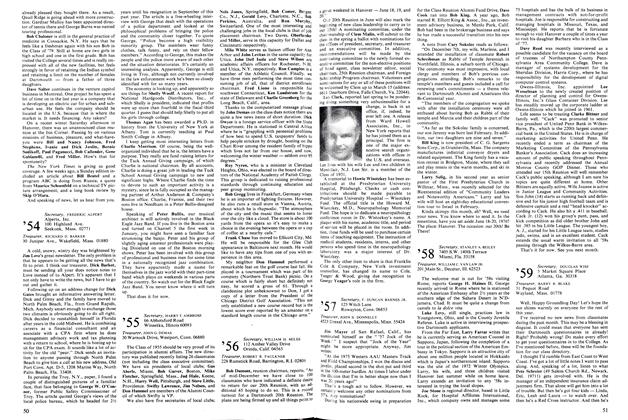

FEATUREThe Bird Listener

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By DAVID HOLAHAN -

Feature

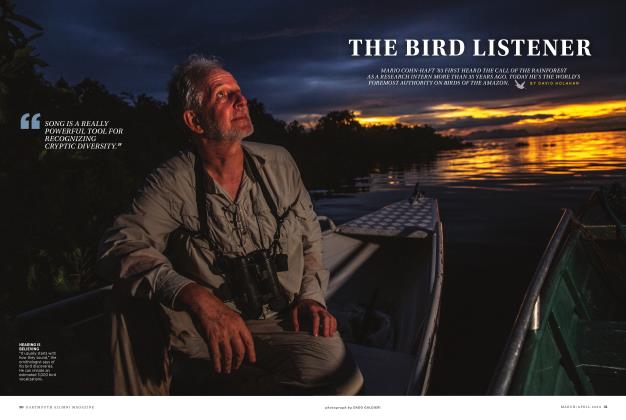

FeatureJames Marsh, Dartmouth, and American Transcendentalism

MARCH 1969 By Douglas M. Greenwood '66 -

Feature

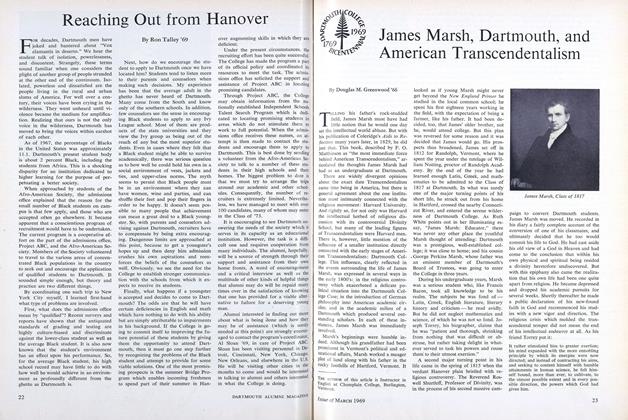

FeatureDartmouth Indian With a Mission

March 1957 By GEORGE W. FRIEDE '27 -

Feature

FeatureHow Does It Feel?

Jan/Feb 2010 By LEANNE MIRANDILLA ’10 -

Cover Story

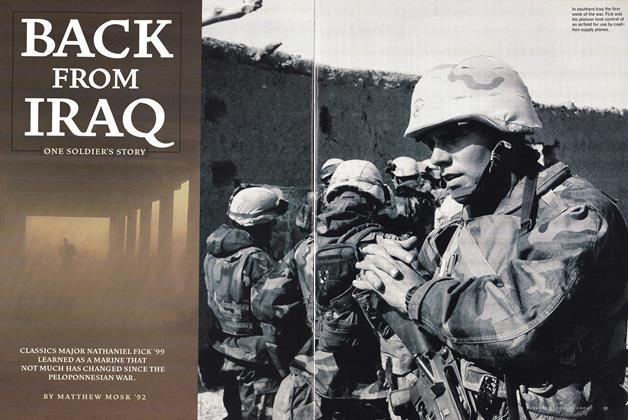

Cover StoryBack From Iraq

Jan/Feb 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Cover Story

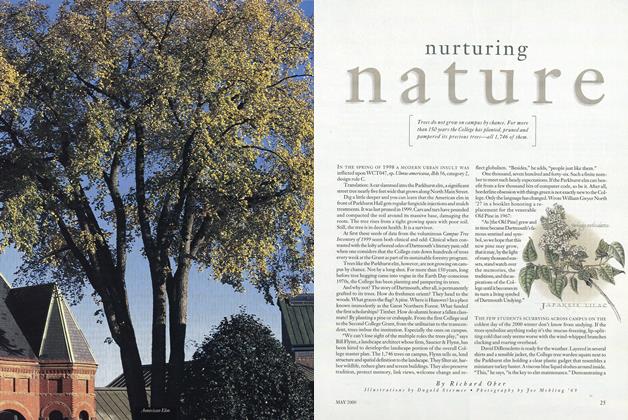

Cover StoryNurturing Nature

MAY 2000 By Richard Ober