SINCE 1958, when the three-three curriculum was inaugurated, the course work of freshmen and sophomores has been supplemented by the required Program of General Reading. Two books, from a list prepared by a steering committee, must be read each term, so that over the two-year period each student reads twelve "important, provocative, timely" books not part of his courses.

The Program has been revised for the current year, with guest lecturers added and with the book list sharply reduced in order to improve its overall quality and to increase the likelihood that a large number of students will read the same book and thus be likely to discuss it.

The 1961-62 reading list could very well serve as a postgraduate course in independent reading for alumni, and to that end we print it here, together with the faculty commentaries provided for the guidance of freshmen and sophomores. Nearly all the books are available in paperback editions, as indicated.

Freshman List

LITERATURE AND THE HUMANITIES

1. Albert Camus: The Plague (Modern Library).

One of the most famous novels in contemporary literature, The Plague dramatizes the ways in which various social groups and various kinds of men confront a public and private crisis. A vivid and disturbing study of man's responsibility to himself and his fellows.

2. Feodor Dostoyevsky: The Devils (ThePossessed) (Penguin Books, L-35).

In The Devils Dostoyevsky uses his power of intense concentration to examine the nature of a social revolutionist. In answer to the social inequality and its consequent unrest which characterized nineteenth-cen-tury Europe and Russia, Dostoyevsky defined social goodness as a mixture of the traditional Russian aristocratic values supported by Christian social justice. But the reader's ultimate attention is focused on the protagonist's fundamental struggle between his own goodness and his own evil.

3. David Hume: Dialogues ConcerningNatural Religion (Hafner Library of World Classics, 5).

A classic examination of the rational arguments for the existence of God. Particular attention is given to an a posteriori argument (the argument from design), though the a priori arguments are considered as well. Hume makes abundant use of dramatic irony, and his command of the language is unsurpassed. Philo, for the most part, expresses the author's views though on occasion Cleonthes plays this role. The editor's introduction is highly recommended.

4. Alan Paton: Cry, The Beloved Country (Scribner Paperback, SL-7).

No one will find in this book only the story of a South African Zulu priest in search of his wayward daughter. In its smallest dimension, the novel mirrors the race problem that strains at the white supremacy rule of the Union of South Africa; on a larger scale, the book confronts us with the struggle for human betterment thai permits no bystanders.

Although most novels that purposely attempt to prod the conscience generally fail in artistic achievement, Paton's skill as a writer and his knowledge of his subject combine to produce one of the superior literary works of our times. Cry, The BelovedCountry has come out of a continent that is torn with strife and overrun with terror, but the story of this land is told with compassion and poignant beauty in a prose style that is somewhat strange but clearly in harmony with the purpose of the narrative.

5. M. de Stendhal: Scarlet and Back (Penguin Books, L-30).

Julien Sorel, the hero of this brilliant and subtle novel, is one of the original outsiders. To see why he did not make it, let de Stendhal pitilessly display the manners and motives of the men - and women — in his life against a rich panorama of early nineteenth-century French society. You will net forget Mile, de la Mole; you may even discover that you already know her.

6. St. John of the Cross: The Dark Nightof the Soul (Ungar, M-110).

Complete union of the individual will with the will of God in perfect love, that and nothing else is the goal of the Christian mystic. No one has better illumined the dark, arduous way, nor analyzed the states of the soul along it, than the great poet and contemplative of the siglo de oro. Mystical experience is an abiding possibility of the human spirit, and one must know it, if only vicariously, to be wholly a man.

7. August Strindberg: Three Plays ("The Father," "Miss Julia," and "Easter") (Penguin Books, L-82).

In The Father, Miss Julia, and Easter the reader finds Strindberg at his most bitter and yet poetically tenderest moments. Through Laura in The Father and Miss Julia, Strindberg's realism mirrors the anxiety he felt in his relationships with women in his search for ultimate personal dignity. Easter however, the most naturalistic and poetically moving of Strindberg's mystical plays, reveals his ultimate love and compassion in his final and classic conviction that through suffering we become whole.

THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

1. Isaiah Berlin: Karl Marx: His Lifeand Environment (Galaxy Books, 25).

More than most men Karl Marx has been praised and blamed for changing the course of world events. Sir Isaiah Berlin of Oxford has compressed in one small volume a care- ful assessment of Marx's role in history, a brief review of his system of political and economic analysis, and an account of the background of events — from family to nation — that influenced Marx and that he, in turn, attempted to influence. The book goes well beyond the usual biography, for Berlin shows Marx's indebtedness to earlier thinkers. For this reason, it is suggested that for readers unacquainted with the field a prior reading of Robert L. Heilbroner's TheWorldly Philosophers will increase appreciation of Berlin's work.

As with most books, deficiencies may be noted. Berlin does not devote enough attention to the development and criticism of the labor theory of value.

2. Robert L. Heilbroner: The WorldlyPhilosophers (Simon and Schuster Paperbound).

Mr. Heilbroner has written in this book one of the clearest and liveliest accounts of the more influential economic thinkers, whom he terms "worldly philosophers." The thesis of his book attempts to justify this phrase. The economists, he claims, sought to formulate a philosophy of man's most worldly activity, his pursuit of wealth, and their ideas, which could not be isolated from man's daily work, have been "world-shaking." Thus his study is not only a careful examination of economics as a science but is as well a vivid and absorbing excursion into biography and social history.

3. Eric Hoffer: The True Believer (New American Library, MD-228 ).

A study of what makes a fanatic - a man who has completely immersed his identity and his will to choose in a cause or movement. The relevance of such a study to the societies of Nazi Germany, Russia, and China, and to the emergent nations of Africa is obvious. Not so obvious, but equally important, is the value of Hoffer's observations on the fanatic in America. One sees how easily "it can happen here." A pungent, well-written, and truly disquieting book.

4. Garrett Mattingly: The Armada.

A combination of scholarship and art in the great tradition of Prescott and Parkinson, this book demonstrates that brilliantly vivid narrative need not be antithetical to historical truth. From a wealth of material gathered all over Europe, the author reconstructs the great struggle between Catholicism and Protestantism in which the adventure of the Spaniards against Elizabethan England was part of the effort to achieve religious unity by force. He concludes that "Of all the kinds of war, a crusade, a total war against a system of ideas, is the hardest to win."

5. Peter Ritner, The Death of Africa.

Any book that attempts to provide an up-to-date survey of the political and social conditions of all of Africa is bound to suffer from hurried preparation and knowledge spread too thin. The work of Peter Ritner, a former editor of the Saturday Review, is no exception. The author's inability to stick to his subject results in wholesale assertions on the value of American culture, education, the "'new capitalism," and the like. His justified but near hysterical indignation at the abuses suffered by the African natives and his confused prescriptions for the solution of the "African problem" get in the way of the main contribution of the book - a factual account of an area of the world about which we know very little. Students should approach this book primarily as a descriptive introduction to the study of Africa, recognizing that both the statement of Africa's problems and their solution require more knowledge and acumen than Ritner is able to command.

6. William Carlos Williams: In the American Grain (New Directions Paperback, p-53).

To be candid, this book of essays on major figures in American history probably does not belong in this section at all. Dr. Williams, a leading contender for the title of "greatest living American poet," comes at the facts through art and imagination, and where the facts are missing, he does not hesitate to supply the ones he thinks should be there. Nevertheless, this is a sensitive and perceptive interpretation of what the dream of America has meant from the days of the earliest explorers to the present. Professionals may be outraged by his methods, but Williams' real theme is what the whole pageant of our nation signifies to us, and for that his methods may be just the right thing after all.

THE SCIENCES

1. Harrison Brown: The Challenge ofMan's Future (Compass Books, c-3).

Some economists are less than enthusiastic about the neo-Malthusian elements in this book, but the facts about available food, fuel, and mineral supplies and the discussion of their effect on international relations are of great importance. Brown's ideas about the role of technology in underdeveloped nations run counter to most popular thinking on the subject and deserve the most careful consideration from all who live in what is now unmistakably one world.

2. Fred Hoyle: Frontiers of Astronomy (New American Library, MD-200).

For millennia men have wondered, "What are the stars?" At last we know — or think we do. They condense from cold hydrogen, expand and contract, change their colors, transmute the hydrogen into other elements, and shine, shine, shine until at last they explods in a glorious supernova. Where does the hydrogen come from? Perhaps, Hoyle suggests, it is continuously being created from nothing. Yet radio waves emitted billions. of years ago by galaxies which collide may disprove his theory.

3. William Irvine: Apes, Angels, and Victorians (Meridian Books, M-78).

The evolution of Evolution, from the Voyage of the Beagle to the Origin ofSpecies, through the debate with Wilber force, the importance of orchids, and the re-education of Victoria's England. The author of this lively account is — a professor of English who says he '"stopped thinking in graduate school and has been writing about other men thinking every since." Not a bad topic at that.

4. Lucretius: The Nature of the Universe (Penguin Books, L-18).

M:chanical materialism has remained a persistent theme in Western thought. For reasons that are interesting to speculate on, the doctrine found its grandest expression in the work of this Roman poet of the first century B.C. From atoms and the void he constructs a universe in which chance and necessity, matter and mind, life and love, society and civilization, all have a naturalistic explanation.

5. Bertrand Russell: The ABC of Rela-tivity (New American Library, MD-258).

Einstein's reconstruction of space and time has revealed a new world, which may be the very one we live in, as we are just beginning to understand. In this lucid and sparkling account, Russell introduces us to that world and to the scope and power of the scientific imagination. Naturally he does not neglect the philosophical implications, which are profound.

6. J. W. N. Sullivan: The Limitations ofScience (New American Library, MD-35).

The wonderful and terrible products of twentieth-century scientists are well known to all, but unfortunately the grandeur of imagination and depth of insight of the best of them are not. Sullivan is no dazzled worshipper at the shrine, but a sensitive interpreter and critic of their new outlook. Humanists will be especially interested in his claim that the true significance of science is found not in its results, but in its attitudes, its moral and aesthetic values, which today as never before are rarely encountered outside it.

Sophomore List

LITERATURE AND THE HUMANITIES

1. Bertolt Brecht: Parables for the Theatre ("The Good Woman of Setzuan" and "The Caucasian Chalk Circle") (Evergreen Books, E-53).

In a sense The Good Woman of Setzuan and The Caucasian Chalk Circle are two ends of the same candle. The former dramatizes an answer to the tortuous question of whether the good can survive in a world that accepts and' even admires evil. Brecht's gods set the world to turning and naively complain about its direction. The second parable offers the hope of good and, ironically, sees it survive only because a "madman" wishes it to. Particularly recommended to those who have read Camus, Kafka, or Dostoyevsky.

2. Etienne Gilson: God and Philosophy (Yale Books, Y-8).

Lectures given at Indiana University by one of the foremost Catholic theologians and philosophers. Gilson offers a distillation and synthesis of the views concerning the relation between our conception of God and the demonstration of His existence as presented in Greek, Christian, and Modern philosophic thought. The writing is characterized by cogent arguments and judicious evaluations. Gilson candidly endorses Aquinas' answer to the metaphysical problem of God and yet avoids the pitfalls of dogmatism.

3. Vladimir Mayakovsky: The Bed Bugand Selected Poems (Meridian Books, M-94).

Mayakovsky has been termed the poet laureate of the Soviets and a wild man of Russian literature. Stalin approved of his work, yet "The Bed Bug" is one of the most bitter attacks on Soviet bureaucracy ever put down. Fabulously talented, he could - and did - write much drivel. This selection shows him at his best: powerful, savage, tender, frantic, sometimes deeply revealing, and almost always exciting.

4. Thomas Parkinson: Casebook on theBeat (Crowell Literary Casebooks, Paper-bound).

Opinions vary greatly concerning the value of the writing of the Beat Generation, but almost all critics agree that they and their philosophy of disengagement represent a significant social phenomenon. This "casebook" offers a representative selection of the best poetry, fiction, and criticism of this group and a number of vigorously expressed opinions for and against its work. Many issues concerning form, style, the role of the artist in America, and the state of our society are raised and the discussion is lively, to say the least.

5. Bertrand Russell: Mysticism and Logic (Anchor Books, A-104).

A collection of wise and witty essays by one of the most influential of contemporary philosophers, which range over such topics as mysticism, science and liberal education, a "free man's worship," mathematics and its metaphysical commitments, and so forth. The book is highly recommended in its entirety, though the student without some preparation in philosophy is advised not to tackle the essay "Knowledge by Acquaintance and Knowledge by Description" (unless he is particularly adventurous).

6. Geoffrey Scott: The Architecture ofHumanism (Anchor Books, A-33).

Out of the chaos of competing a priori theories of what architecture must be, Scott attempts to derive a coherent and reasoned view based on the histories of taste and ideas. After tracing the course of the theories and criticizing the caprices and prejudices they reveal, Scott concludes that the greatest values are to be found in an architecture based on humanism — an architecture in which mass, space, and line "respond to human physical delight." This is a stimulating and provocative book packed with valuable information.

7. Tsao: Dream of the Red Chamber (Anchor Books, A-159).

Caught in the complex web of Chinese family life, the tender love of Pao-yu for Black Jade encounters difficulties undreamed of by Romeo and Juliet. According to one of her scholars, "If you wish to understand China at all, you must read her poetry and Dream of the Red Chamber

THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

1. Walter Lippmann: The Public Philosophy (New American Library, MD-174).

The Public Philosophy is a disturbing criticism of Western democracy's willingness to survive against modern totalitarianism. In Lippmann's exposure of the public's cancerously pernicious abandoning of its role as the moral conscience of democratic institutions, we gain a new perspective on McCarthyism and the John Birchers. ThePublic Philosophy is not for those who smugly and defensively assume that democracy per se is the final answer to man's political and social problems.

2. Marvin Meyers: The Jacksonian Persuasion (Vintage Books, v-102).

From his reading of such diverse sources as Tocqueville and Cooper, Leggett and Sedgwick, Marvin Meyers constructs the intellectual and social milieu that characterized America at the beginning of its industrial revolution and which determined our character for 125 years. In sharp focus TheJacksonian Persuasion discusses the Bank controversy in all its now tragicomic aspects, the decline of the political-aristocratic temperament, and the success of the Protestant Ethic in America. The reading of Meyers' work throws much light on the modern American political character.

3. Clinton Rossiter: The American Presidency (New American Library, MD-267).

The American Presidency is Clinton Rossiter's amazingly readable discussion concerning the growth and structure of the Western world's most powerful office. Especially valuable is Rossiter's analysis of the traditional and often bitter antagonism between the Congress and the President, of the forces which have determined the unprecedented growth of executive power, and of the unique manner by which the office reflects the character of the American people. Those readers who enjoy discussing political "battling" averages will be interested in Rossiter's specific and frankly bissed judgment of F. D. R., Harry S. Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

4. W. W. Rostow: The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (Cambridge University Press Paperbound).

Although public discussion of economic growth has somewhat waned since the recent national election, the questions disputed during this campaign are no less important today. W. W. Rostow, an economic historian on leave from M.I.T. as a presidential adviser, has written a book that will provide both an understanding of the nature and significance of economic growth and an account of its historical occurrence in widely differing areas of the world. The "stages of growth" should be recognized - as the author emphasizes — as essentially arbitrary categories by which historical events can be arranged and dramatized, rather than as inevitable steps in a continuum of economic development.

5. W. Sluckin: Minds and Machines (Penguin Books, A-308).

The discovery that machines exhibiting adaptive and purposive behavior can be built has important consequences for the scientific study of perception, learning, and thinking. Sluckin gives a readable survey of developments in this exciting field.

THE SCIENCES

1. Claude Bernard: An Introduction tothe Study of Experimental Medicine (Dover Paperbound).

An unsurpassed study of the use of the experimental method in the medical sciences, richly illustrated by the personal experiences and reflections of the great nineteenth-century physiologist. Few books give so intimate a glimpse of the creative scientist at work.

2. E. A. Burtt: The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science (Anchor Books, A-41).

The views of the universe of Copernicus were in no way more empirically demonstrable than those of Ptolemy, but they were simpler and eventually led to changes in attitude that initiated what we know today as modern physical science. In this development there have been many contributors and those mentioned on the book jacket — Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, Hobbes, Gilbert, Boyie, and Newton - are but a few of the giants whose works are critically examined by Burtt. Clearly the scientists work not by laboratory alone and this study provides assistance in understanding both the methods and accomplishments of the early innovators.

3. Herbert Butterfield: The Origins ofModern Science (Macmillan Paperbacks).

An eminently thoughtful account of the development of modern science from 1300 to 1800. The scientific revolution required the rejection of ancient and medieval authorities, and resulted in a radically new "world view" - a novel conception of man and his relation to the universe which dominates contemporary thought. Butterfield's estimation of the significance of the evolution of modern science is indicated by his statement that "It outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and Reformation to the rank of mere episodes, mere internal displacements within the system of Medieval Christendom." This is a history but it is not primarily concerned with the chronology of events. Rather, attention is focused on those pivotal moments in the development of modern science which demanded alterations in man's total mentality. Butterfield deals not only with the fruitful hypotheses but with the errors and blind alleys which themselves were determinants of the course of scientific thought.

4. Werner Heisenberg: The Physicist'sConception of Nature.

The older scientific world view claimed to be a picture of nature as such. Nobel Laureate Heisenberg shows how this view has changed, and how modern physics has come to offer instead a picture of man's relation to nature, from which the scientist as observer and interpreter cannot in principle be excluded.

5. J. Z. Young: Doubt and Certainty inScience (Galaxy Books, 34)

A distinguished contemporary biologist discusses our knowledge of brain function, the symbolic nature of communication, the intelligence of the octopus, and many related topics in this stimulating and wide-ranging book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Cold War and Liberal Learning

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

November 1961 -

Feature

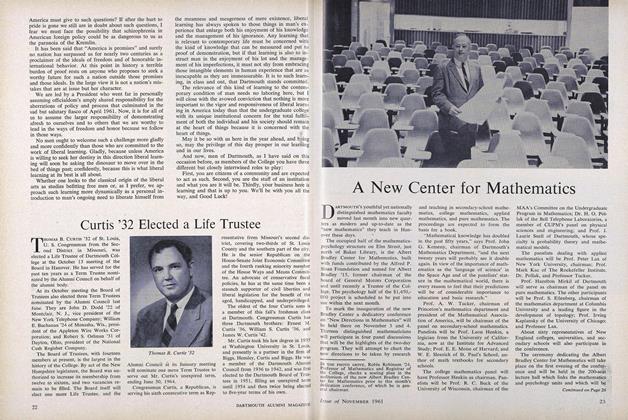

FeatureA New Center for Mathematics

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureHOW THE "IVY LEAGUE" GOT ITS NAME

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Meet in Hanover

November 1961 -

Feature

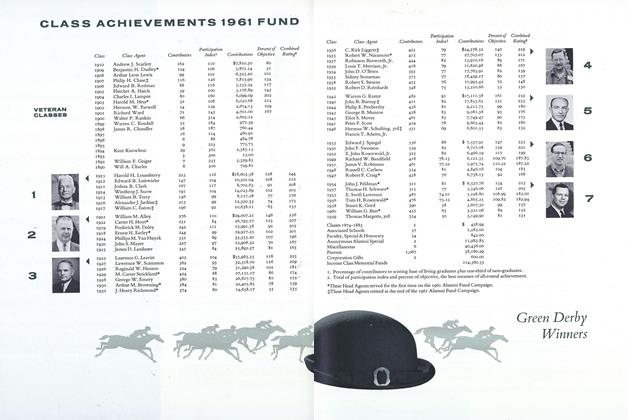

FeatureLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1961 FUND

November 1961

Article

-

Article

ArticleImportant Trustee Meeting

April, 1911 -

Article

ArticleTrustees Elect Five to Faculty Chairs

March 1960 -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Symbol (cont.)

November 1983 -

Article

ArticleTwo Poems Diverged in a Mellow Mood

June • 1988 -

Article

ArticleGuam

DECEMBER 1970 By FRANK COUPER '68 -

Article

ArticleInvesting in Brainpower

Nov/Dec 2003 By Kate Lilienthal '88