President Dickey's 1961 Convocation Address

WE are privileged this morning to gather for the purposes of peace, but it has been a close thing. Indeed, it has been a closer thing this summer than men should pretend to calculate. Once great nations publicly assume the posture of war toward each other, like school boys squared off with precariously balanced chips on their shoulders, no one can be sure what comes next. Let us hope that at least this common truth is never lost to sight in either Moscow or Washington.

Just seven days ago this morning the inscrutable hand of tragedy took the life of a valiant man. Death is always an awful teacher, but the death of a great man at the height of his effort makes his life a lesson for all mankind. If the lesson of Dag Hammarskjold's life and death escapes us, there is surely no learning here or elsewhere in the world that can save us from becoming a footnote on the pages of history's unlearned lessons. Let us pay this man's work the only tribute he coveted - our commitment to it.

At such a parlous time one wonders what can usefully be said in public by private persons. The temptation is strong either to stay silent or to indulge oneself by castigating the foe. Manifestly a fresh measure of such castigation is merited, but it is also evident that there is no shortage of tongues eager to perform this service. Understandably there are fewer of us standing in line to speak of those things which as a nation we ought to have done but have left undone, let alone those things which we have done and ought not to have done.

One good but terrifying reason why such reticence in self-examination grows among us is the spreading conviction on the part of Americans that short of "rolling over and playing dead" there is nothing we could do that would make any real difference in Kremlin policies, that is nothing except being just as ruthless and rough, just as conspiratorial and unreliable, in fine, just as fundamentally unapproachable as the Soviet leaders themselves.

Silence, at such a time, is human in another respect. Whether out of a sense of fellow feeling or some personal experience with these things, most of us strongly prefer not to make the road any rougher than it is for the hard pressed, able men who manage the foreign affairs of our nation and who but for the Grace of God - and a few thousand votes - would still be as omniscient as the rest of us. Moreover, I am sure that in world affairs, as the marriage experts tell us is true in marital affairs, leaving a few things unsaid each day is the most potent secret weapon of all.

I cannot put such considerations wholly aside and I should not myself today venture public utterances about the cold war for the purpose of offering gratuitous advice either to. Mr. Khrushchev or to those whose business it is to represent us in these matters. I have decided to say what I do because what we are as a nation is the business of education and as far as you and I are concerned the time to decide what that is to be is now.

Silence ceases to be golden when it masks from ourselves as well as others our most fundamental character and our deepest concerns. A progressively stifled democratic process does just that. My concern today is to suggest that we have reached a point in the cold war where along with the risk of war we must reckon with the fact that it will not profit America to "win" any struggle if thereby as a nation we lost our character, or as the Bible would put it, our soul.

We now know for a certainty that, at best, the twilight of the cold war will be indefinitely prolonged. From here on for a long time nothing is going to be "normal," not even the emergencies. In the course of our growing up as a nation we have learned to live with the kind of war-time emergency in which by common consent, for the selflimiting period of a shooting war, we suspended democratic prerogatives and practices, as we said, "for the duration." We met the "clear and present danger" of these emergencies confident that in relatively short order we could and would return to our normal ways by simply throwing off the limitations on liberty we had ourselves invoked.

Civilians - and junior military officers - have long taunted generals with the charge that they always prepare to win the last war, not the next one. And yet our civilian leaders in public and private life will, I think, be committing the same folly if they attempt to lead America through the endemic and endless "crisis" of the cold war on an emergency basis.

Consider but these two difficulties. In the first place., taking human nature for what it has been up to now, is there good reason to believe that we (not to speak of our varied allies) could sustain a sense of emergency for a generation or so? And one only needs to recall the fable about the danger in the repeated shouting of "wolf" to be aware of the cumulative peril to the nation of any attempt, however sincere and justified by circumstances, to sustain an alert and resolute national mood by repeated invocations of an emergency spirit.

And even if we should somehow be successful in sustaining a mood of war-time emergency for another generation, what would we have? My fear is that we would have a nation that had lost its appetite for freedom and forgotten how ever again to make the democratic process work. Let us never underestimate what even one generation of such indoctrination can do to a people. The Soviet itself provides the most instructive example we could have.

No, if we are to win, or even to coexist as a free society, we must continue to exist as a free society. Over the long pull we now face we must preserve the democratic process, not by leaving it behind us piece by piece as the going gets steeper, but by taking it with us to new levels of maturity and effectiveness. Even if the going is never easier in our time and if, as often in the past, an unforeseen future needs to rescue our beleaguered present, a better future will know where to look for us and our rescue will be worth the effort because we stayed on the course free men have always set for themselves.

On this course we need to talk with each other, even on occasion to argue out which way is up. Certainly silence about such things is not good for America and conversely neither will self-criticism on such terms give comfort to a foe whose ways we wish to follow no more by mistake than by design.

In point of time we are today able to examine our position at a moment when the Soviet by flaunting its perfidy in negotiations that concerned all mankind has made us, as the phrase goes, "look good." And there is surely no more propitious place for checking the course of a free society than in a historic college whose commitment to man's fulfillment in freedom antedates even our nation's birth.

Beyond these considerations of time and place that bid us be bold in self-examination, there is the great, overriding fundamental that we cannot hope to win for our purposes and our ways by beating the Soviet Union at its own game of secrecy, duplicity, and self-deception. Champions in all fields know many good reasons for not playing the other fellow's game, but in this great contention which we call the cold war I suggest that there is one imperative reason for not doing it: there are simply too many decent people everywhere who don't care who wins that sort of a game, who won't play the part of pawns in it, and who ultimately will be content to see the participants in such a struggle fall of their own futility. This, I assume all would agree, is not the way we want anyone to feel about America or any cause to which she commits her might. We neither want it nor can we afford it.

And yet do we.even now recognize how close we came last April to putting our cause in this light? Confronted as we are with Castro's pathologies and provocations, can we yet see the extent to which the Cuban affair revealed American foreign policies and our democratic process were being compromised by the cold war? I put it this way because I think we reckon only with the superstructure of what we hit if we dispose of this fiasco as simply a tragic miscalculation in an intelligence operation or as merely a bad round in a wholly honorable opposition to the perversions of Fidelismo.

Test the matter by trying on yourself the view of some: that the only thing wrong with our part in this whole: business was that it failed. Assume, if you will, that it had "succeeded" and that an American sponsored regime governed in Cuba today: what would be the outlook for mutual respect and trust between us and the nineteen other independent nations of Latin America in the decisive decade ahead; where would the promise of our Alliance for Progress with those nations be today? If it had "succeeded" would there be any stopping those among us who would commit this nation to the dead-end hope that we really can beat international communism at its own game of conspiratorial imperialism? If it had "succeeded" would future public assurances by our highest officials concerning our non-involvement in such things elsewhere be likely to pass current within our own democratic process, let alone in the marketplaces of public opinion throughout the world? Could a great nation committed to such poli- cies ever hope to lead the United Nations into a new era of greater effectiveness?

Can there long be any great doubt about the answer America must give to such questions? If after the hurt to pride is gone we still are in doubt about such questions, I fear we must face the possibility that schizophrenia in American foreign policy could be as dangerous to us as the paranoia of the Kremlin.

It has been said that "America is promises" and surely no nation has surpassed us for nearly two centuries as a proclaimer of the ideals of freedom and of honorable international behavior. At this point in history a terrible burden of proof rests on anyone who proposes to seek a worthy future for such a nation outside those promises and those ideals. In the large view it is not a nation's mistakes that are at issue but her character.

We are led by a President who went far in personally assuming officialdom's amply shared responsibility for the aberrations of policy and process that culminated in the sad but salutary fiasco of April 1961. Now, it is for all of us to assume the larger responsibility of demonstrating afresh to ourselves and to others that we are worthy to lead in the ways of freedom and honor because we follow in those ways.

No men ought to welcome such a challenge more gladly and more confidently than those who are committed to the work of liberal learning. Gladly, because unless America is willing to seek her destiny in this direction liberal learning will soon be asking the dinosaur to move over in the bed of things past; confidently, because this is what liberal learning at its best is all about.

Whether one looks to the classical origin of the liberal arts as studies befitting free men or, as I prefer, we approach such learning more dynamically as a personal introduction to man's ongoing need to liberate himself from the meanness and meagerness of mere existence, liberal learning has always spoken to those things in man's experience that enlarge both his enjoyment of his knowledge and the management of his ignorance. Any learning that is relevant to contemporary life must be concerned with the kind of knowledge that can be measured and put to proof of demonstration, but if that learning is also to instruct man in the enjoyment of his lot and the manage- ment of his imperfections, it must not shy from embracing those intangible elements in human experience that are as inescapable as they are immeasurable. It is to such learning, in class and out, that Dartmouth stands committed.

The relevance of this kind of learning to the contemporary condition of man needs no laboring here, but I will close with the avowed conviction that nothing is more important to the vigor and responsiveness of liberal learning in America today than that the undergraduate college with its unique institutional concern for the total fulfill ment of both the individual and his society should remain at the heart of things because it is concerned with the heart of things.

May it be so with us here in the year ahead, and being so, may the privilege of this day prosper in our learning and in our lives.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

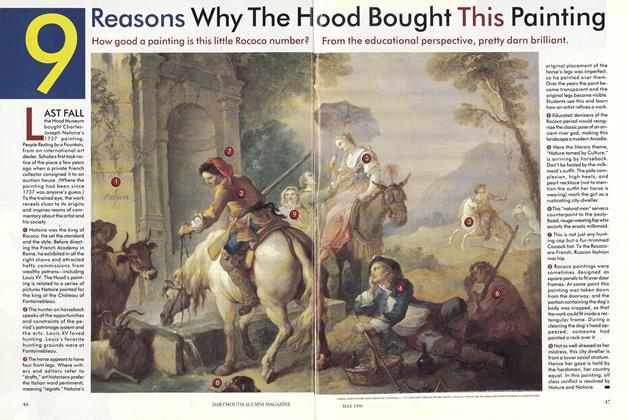

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

MAY 1996 -

Feature

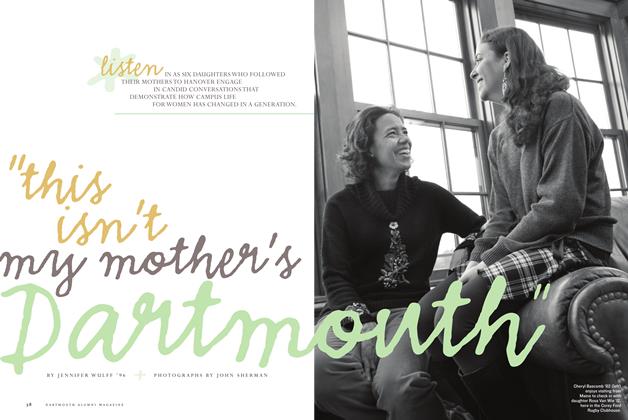

Feature“This isn’t My Mother’s Dartmouth”

Sept/Oct 2010 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureTHREE POEMS

January 1958 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Feature

FeatureThe Crown of Columbus

June 1992 By Michael Dorris and Louise Erdrich '76 -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22