One of the eleven youngDartmouth graduates atOxford this year describesthe ancient and modernfacets of an educationalexperience quite removedfrom one's college coursein this country.

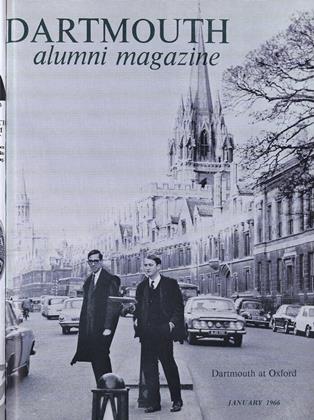

OXFORD is easily the most celebrated university in the world. But the Oxford of today is far different from that of the 1890's and 1920's which gave the university its image and its great renown. The Oxford of Gladstone, Oscar Wilde, Lewis Carroll, and Lawrence of Arabia, of quiet afternoons on the river or the lawns with a glass of port, of privilege and rank and aristocracy, is slowly disappearing. In its place is emerging a new university that is a curious combination of ancient and modern, of arts and sciences, and of such opposite personalities as Sir Alec Douglas-Home, Harold Wilson, and Dean Rusk. Despite the pressures of the 20th Century that are remolding American universities, Oxford retains much of its old charm and there is still a uniqueness about its colleges and curriculum - a uniqueness that draws Dartmouth men to Oxford every year.

Victorian and Edwardian Oxford in the heyday of the British Empire must have been a glorious place. A successful career at Oxford was the first step to a career in the Empire and Oxford politics were Imperial politics writ small. A speech in the Oxford Debating Union was a debut for the House of Commons. The image of this old Oxford lingers on - perhaps unduly perpetuated in the popular novels of Evelyn Waugh and Max Beerbohm — as a university of dreaming spires, idle ways, and of brilliant aristocratic undergraduates who shocked England and all the world by their audacity and cleverness. Today, Oxford lives in the shadow of this past, trying in some ways to duplicate it, in others to surpass it. And here, in brief, we have both the successes and failures of 20th century Oxford.

Modern Oxford is unquestionably many things to many different people but few question that Oxford is essentially its buildings. This is the part of Oxford that has truly withstood change. The majesty of Christ Church College, the serenity of the deer park and long walks of Magdalen, the dignity of ancient New College leave a lasting impression on their inhabitants. Indeed, the buildings seem to be the great conserving force about Oxford; while all else may change, the quadrangles and halls remain the same. A great part of Oxford is 14th and 15th Century and though restoration is necessary, the rebuilding is generally faithful to the original plans. Just now the ancient buildings are being cleaned of the dirt and soot from the Industrial Revolution, and they now have more of their original beauty and grace than has been visible for centuries. The retention of much that is ancient in its buildings has had a great effect on the academic and social atmosphere of the university. The buildings seem imperturable; so do the Oxonians.

Many undergraduates still read Latin and Greek, the staple of the old university, for their three or four years "up" at a college. Other disciplines have only slowly and somewhat reluctantly been accepted by the university, so that whereas Oxford is pre-eminently the university for the study of classics, history, and literature; other English universities successfully compete for students in the more modern disciplines of economics, psychology, and the sciences. Even under pressure from investigating committees (the Lord Franks commission is the present one) Oxford mends its ways very slowly and tradition has succeeded in keeping out new methods and ideas. For example, English literature at Oxford means Anglo-Saxon, to the woe of many undergraduates. History, with the exception of one paper, stops at 1914, and politics can be studied on the undergraduate level only in conjunction with economics and philosophy. But criticism of the syllabus must be mixed with praise, for the Oxford philosophy of education is frank and no-nonsense - it is to give the undergraduate a thorough academic grounding in a single discipline rather than to prepare him for "life" or for an occupation. Neither business nor sociology is taught at Oxford. Anthropology and art history are only for graduate students.

The tutorial system is the heart of the Oxford education and, like everything else, is organized by the colleges. The success or failure of the weekly tutorial, at which the student reads an essay on a pre-arranged subject, is largely the student's own responsibility. Other than the tutorial, there are only lectures which vary greatly in quality and are entirely voluntary - they are sparsely attended. Tutorials and lectures are designed to prepare the student for the great marathon of "schools" examinations at the end of his degree course (usually three years), the successful completion of which qualifies him for a B.A. degree that is in time transformed to an M.A. The reaction of Americans to the Oxford system is generally unanimous: they favor the tutorial system as a means of meeting great authorities on a personal and challenging level, but they often dislike the little attention given to students by "dons" outside the tutorial.

The greatest complaint from American scholars is generally about libraries. Each college has its own library which is useful for general work but unsuitable for detailed and research work. On the other hand, Oxford's great central libraries, including the Bodleian, are well provided but do not lend books and have a cataloguing system that is hopelessly outdated. To Oxford librarians, a library is a place where books are stored; readers are nuisances.

By far the greatest advantage of the Oxford system is the independence it provides the student. Each student upon entering his college is given a moral tutor and a work tutor, whom he may consult as he sees fit; both tutors leave the student to his own interests and allow him to make of his university career what he will. Other than the weekly tutorial and occasional lecture, the only requirement is that the student spend a specified number of nights within his college and take the necessary examination at the end of his three-year course. Otherwise he is completely free. Terms are eight weeks and the student may then either return to his home for independent work or travel. Most use vacations - six weeks at Christmas and Easter and three months in the summer - for both reading and traveling, and this is one of the most popular features of Oxford for Americans. This past summer, for example, Larry Ayres '64, a Keasbey Scholar in New College, was awarded an Oxford University Prize for the study of French cathedral art. The independence allowed by Oxford makes for some casualties, but the main result is that the student best learns his own interests, under his own power and in the absence of any pressures.

As one of Europe's greatest universities, Oxford has long attracted the West's foremost scholars and students. England's connections with Commonwealth nations also bring many of the best African and Eastern students to Oxford, in much the same way that Rhodes and Marshall Scholarships attract Americans and Canadians.

Oxford is the nurse of British classical learning and the most famous dons are usually eccentric classics scholars. The result of this penchant for ancient Greece and Rome seems to be that more English know the topography of ancient Troy than they do of their own Isles! The four-year course of Literae Humaniores (popularly called "Greats") still attracts a substantial percentage of the best undergraduates and confers an inordinate prestige on those reading it. At the end of the first two years a "Greats" man must take Honour Moderation exams in Latin and Greek prose and verse. Success in "mods" enables the student to continue on for two years in "Greats" - ancient history, classical literature, and philosophy. The course is extremely demanding and requires a first-class intellect; and a good degree in "Greats" is a ticket for future success. For example, the Foreign Office has traditionally accepted only those men who received a First or very good Second Class degree in "Greats."

Modern History is the most popular degree course at Oxford, partly because it allows for a great breadth in reading, and partly because of the controversial Oxford historians. Undergraduates are required to do courses in English history from the Roman conquest to 1914, in constitutional or economic documents, in a general European subject, and in a special subject of their choosing. Historical work is in much greater depth than at the undergraduate level in the United States and the B.A. degree in history corresponds to the M.A. in America. Nonetheless, like most other syllabi, the history syllabus is outdated and needs reformation. The only American history course available to undergraduates is on Slavery and Secession (1850-1862), intolerably little for a university that is endlessly fascinated by American affairs.

Oxford historians are justly famous for their vicious in-fighting and well-publicized prejudices. Regius Professor of Modern History Hugh Trevor-Roper is the current enfant terrible and his feud with A. J. P. Taylor is part of the history of history. When Trevor-Roper was awarded the Regius Professorship over Taylor the decision made national headlines and the feud gained the proportions of a major war. Other historians of world renown at Oxford include Christopher Hill (named this year as Master of Balliol College), Allan Bullock, R. W. Southern, and Sir Isaiah Berlin.

The modern "Greats" - Politics, Philosophy, and Economics - is the most popular course at Oxford for Americans following an undergraduate degree. In some ways PPE is the best of the old and new Oxford for it combines the old approach to politics (as history) and philosophy with the more modern methods of contemporary politics and economics. Students must complete two courses in each discipline and then two extra courses in any single field. Oxford philosophy is "logical positivism" and its foremost advocates are in the university. A. J. Ayer, Gilbert Ryle, and Peter Strawson are the outstanding names in Oxford philosophy and though often inaccessible to undergraduates, are the subjects of countless stories, as when A. J. Ayer (author of Logic, Truth, andLanguage) was confounded by Eartha Kitt in a television interview on the meaning of love!

English literature is a popular subject also but has particularly suffered from Oxford's reluctance to accept change. Modern literature is completely ignored for academic purposes and despite the presence of poet Robert Graves and critics Lord David Cecil and Nevill Coghill, the syllabus is strongly slanted to Anglo-Saxon and pre-Elizabethan literature. In defense of this traditional outlook, one English don is reported to have said, "Before 1900 there is good literature, after 1900 there are only books."

The inability or unwillingness to adapt new subjects to the syllabus and to utilize new techniques has seriously damaged progressive research in the university. Psychology has just been accepted as an undergraduate course of study, again not by itself but in conjunction with philosophy and physiology. Suffering most have been the physical sciences, very much the victim of tradition, a strongly prejudiced Arts faculty, and a nation unable to make great investments in new and untried science. Oxford is not pre-eminent in science as it is in other fields, but this is not to deny the quality of the work done here. The university has its Nobel Prize winners, and the science grounds, between the colleges and the university parks, are the most rapidly expanding area of the university.

Oxford, however, is much more than an educational institution; if it were not, its reputation might be much less than it is. For Oxford is also the pinnacle of the English social system, and as such has no real American equivalent. To be "up at Oxford" is a magical confirmation of status as well as ability, and though Oxford is becoming more egalitarian as English society is opening, the university still has an old-world aura of privilege and rank. Friedrich Engels, Marx's English friend, condemned Oxford as the last remnant of the Middle Ages.

English schoolboys prepare specifically for places at either Oxford or Cambridge and follow a course of study at school that is preparatory for a course at the university. Thus from the age of twelve or thirteen most students capable of gaining university places are educated and socially trained with basically one purpose in mind - admission to Oxford or Cambridge. There are other universities, the "redbricks" plus London and Trinity College, Dublin, but they are educational institutions and lack the mystique of the two ancient universities.

Once admitted to a college, the student's individuality and character (largely a product of his school) are ferociously respected. The student is left to make his own way and his own friends; there is no orientation and no freshman insignia, for example. Rules are lax and the colleges make great effort to provide their gentlemen with all the amenities of privileged life. Each student has a "scout" or servant, now usually shared by several students, who awakens him in the morning, always addresses him as "Sir," puts out his clothes, polishes his shoes, and cleans his rooms and dishes. Women are allowed in the rooms until late in the evening and all colleges maintain beer cellars for drinking before and after meals. Christ Church allows no women in its hall except the Queen; New College, the most liberal of the colleges, tolerates women guests in both the hall and the beer cellar. College life is incredibly civilized for the Fellows regard their students as gentlemen, and the students generally live up to their expectations.

Undergraduate parties are often blacktie and it is on this social side that new Oxford most closely duplicates the past. Many students form small select dining clubs, meet fortnightly, and are chiefly distinguished for their blue-blooded snobbishness. Some count themselves failures if they are not at a party or "sherry" every evening during term, and this social earnestness tends to surprise most Americans, for .this is far different from our occasional fraternity parties. Lords, knights, and maharajahs are sought for parties as their presence supposedly makes a success of the party as well as of the host. This side of Oxford, indeed of England, is at the same time mysterious and exciting to Americans, unaccustomed to this social deference and rank. But it is merely one of the aspects of Oxford life that make it so unlike life in any American university.

Oxford cannot be readily defined. There is no single image; each college is different and students within a college likewise differ. The buildings are the visible university and may well be here forever; life within them only slowly changes and this is the essence of Oxford.

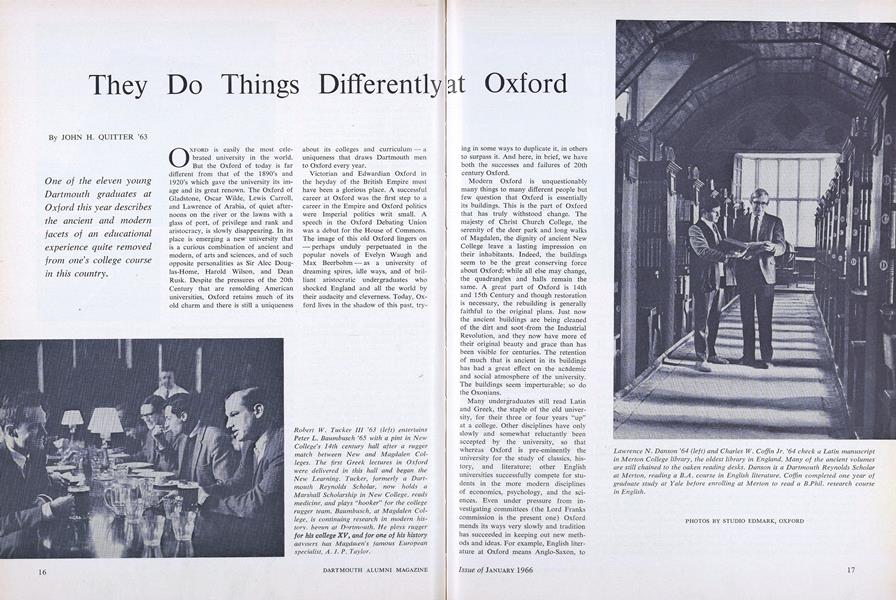

Robert W. Tucker III '63 (left) entertainsPeter L. Baumbusch '65 with a pint in NewCollege's 14th century hall after a ruggermatch between New and Magdalen Colleges.The first Greek lectures in Oxfordwere delivered in this hall and began theNew Learning. Tucker, formerly a DartmouthReynolds Scholar, now holds aMarshall Scholarship in New College, readsmedicine, and plays "hooker" for the collegerugger team. Baumbusch, at Magdalen College,is continuing research in modern history.becun at Dartmouth. He plays ruggerfor his college XV, and for one of his historyadvisers has Magdalen's famous Europeanspecialist, A. J. P. Taylor.

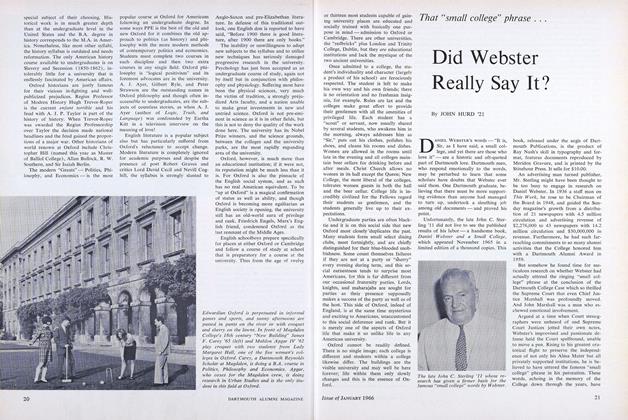

Lawrence N. Danson '64 (left) and Charles W. Coffin Jr. '64 check a Latin manuscriptin Merton College library, the oldest library in England. Many of the ancient volumesare still chained to the oaken reading desks. Danson is a Dartmouth Reynolds Scholarat Merton, reading a B.A. course in English literature. Coffin completed one year ofgraduate study at Yale before enrolling at Merton to read a B.Phil, research coursein English.

John H. Quitter '63 (left) and Larry M.Ayres '64 (right) walk in New College's14th century cloisters with Sir WilliamHayter, the Warden of New College. SirWilliam served as Great Britain's ambassador to Russia from 1953 to 1957, andnow as Warden he is head of the Fellowsand represents New College at officialfunctions. The cloisters, among the mostenchanting in England, served KingCharles I as headquarters and armouryduring the Puritan Revolution. New College, along with Balliol, Magdalen, ChristChurch and Merton, is one of the mostfamous of the Oxford colleges that haveplayed an important part in the historyof the British Empire. Quitter, a Dartmouth Reynolds Scholar, is reading history at New College, specializing inAnglo-French diplomacy. He has writtenfor Oxford magazines. Ayres is a Keasbey Scholar in New College reading fora B.Litt. degree in medieval art. Thispast summer he won an Oxford University Prize for the pursuit of his researchon the continent.

Nevin D. Schreiner '64 (left) and Vallance A. Wickens III '64 stop on MagdalenBridge before taking a punt (a long flatbottomed boat) on the Cherwell River. Behindthem rises Magdalen College tower. At dawn, May Morning, undergraduates congregate on the bridge and in punts on the river to hear choir boys sing Latin hymnsfrom the tower. Schreiner is reading English literature at St. Edmund Hall, the onlymedieval hall remaining at modern Oxford. Wickens is reading PPE (politics, philosophy and economics) at University College, the oldest of the Oxford colleges. University has claimed Alfred the Great as its founder, but the claim is disputed. Schreineris a Dartmouth Reynolds Scholar, Wickens a Fulbright Scholar.

Edwardian Oxford is perpetuated in informalgames and sports, and sunny afternoons arepassed in punts on the river or with croquetand sherry on the lawns. In front of MagdalenCollege's 18th century "New Building" JamesF. Carey '65 (left) and Mahlon Apgar IV '62play croquet with two students from LadyMargaret Hall, one of the five women's colleges in Oxford. Carey, a Dartmouth ReynoldsScholar at Magdalen, is doing a B.A. course inPolitics, Philosophy and Economics. Apgar,who coxes for the Magdalen crew, is doingresearch in Urban Studies and is the only student in this field at Oxford.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

January 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureThe HIGH COST of Running a College

January 1966 -

Feature

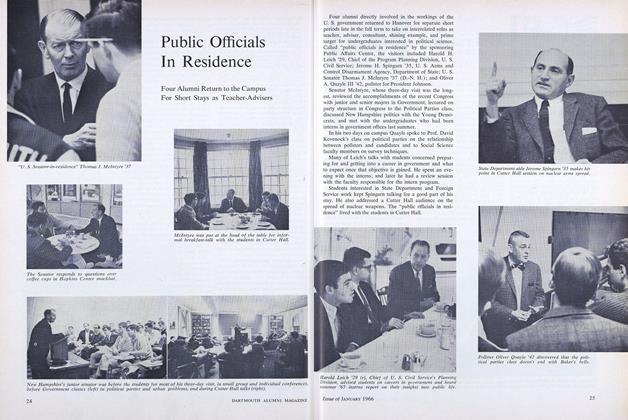

FeaturePublic Officials In Residence

January 1966 -

Article

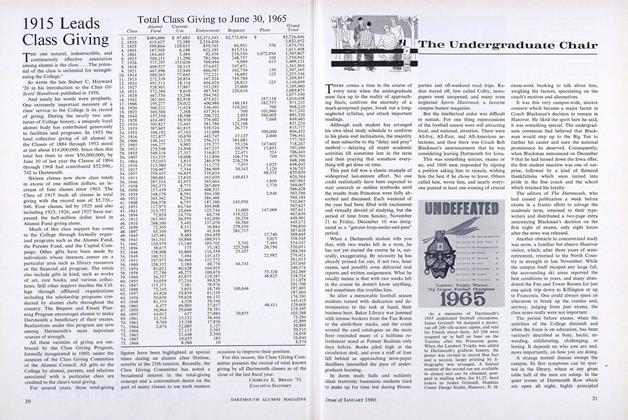

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

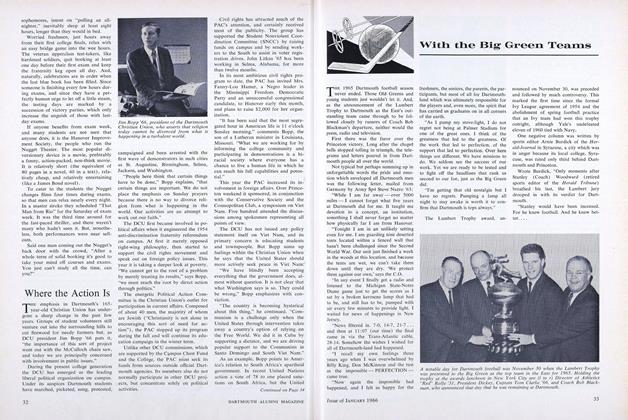

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

January 1966 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

January 1966 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARROLL DWIGHT, EUGENE HOTCHKISS1 more ...

Features

-

Feature

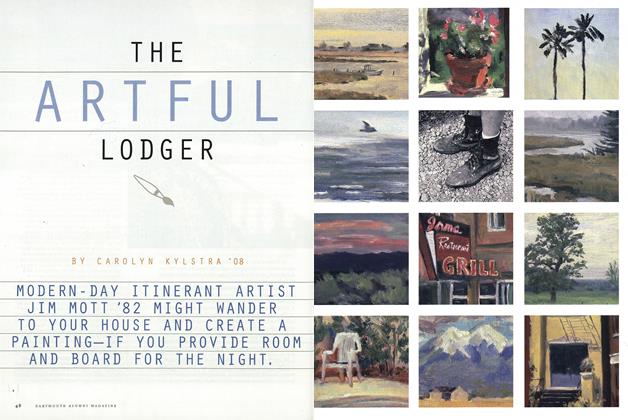

FeatureThe Artful Lodger

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

Sept/Oct 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 5 MINUTE GUIDE TO THE COLLEGE GUIDES

Nov/Dec 2000 By JON DOUGLAS '92 & CASEY NOGA 'OO -

Feature

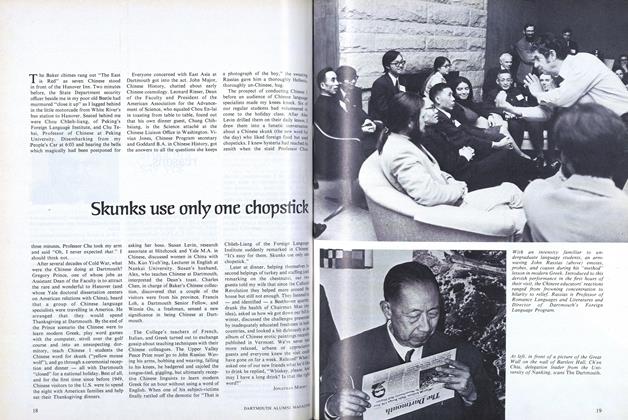

FeatureSkunks use only one chopstick

January 1974 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Feature

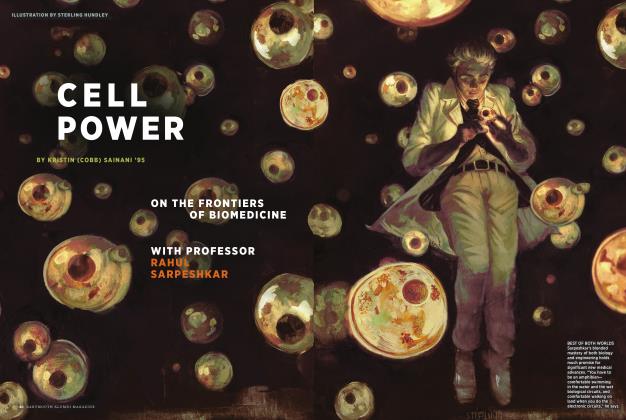

FeatureCell Power

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By KRISTIN (COBB) SAINANI ’95 -

Cover Story

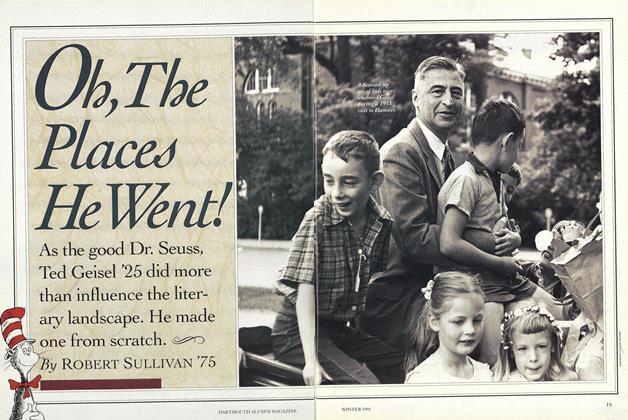

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75