Arnold Toynbee, famed historian, views us with British eyes, and asks a disturbing question

A MERICA has been made the great country that she is by a series of creative minorities: the first settlers on the Atlantic seaboard, the founding fathers of the Republic, the pioneers who won the West. These successive sets of creative leaders differed, of course, very greatly in their backgrounds, outlooks, activities, and achievements; but they had one important quality in common: all of them were aristocrats.

They were aristocrats by virtue of their creative power, and not by any privilege of inheritance, though some of the founding fathers were aristocrats in the conventional sense as well. Others among them, however, were middle-class professional men, and Franklin, who was the outstanding genius in this goodly company, was a self-made man. The truth is that the founding fathers' social origin is something of secondary importance. The common quality that distinguished them all and brought each of them to the front was their power of creative leadership.

In any human society at any time and place and at any stage of cultural development, there is presumably the same average percentage of potentially creative spirits. The question is always: Will this potentiality take effect? Whether a potentially creative minority is going to become an effectively creative one is, in every case, an open question.

The answer will depend on whether the minority is sufficiently in tune with the contemporary majority, and the majority with the minority, to establish understanding, confidence, and cooperation between them. The potential leaders cannot give a lead unless the rest of society is ready to follow it. Prophets who have been "without honor in their own country" because they have been "before their time" are no less well-known figures in history than prophets who have received a response that has made the fortune of their mission.

This means that effective acts of creation are the work of two parties, not just one. If the people have no vision, the prophet's genius, through no fault of the prophet's own, will be as barren as the talent that was wrapped in a napkin and was buried in the earth. This means, in turn, that the people, as well as the prophet, have a responsible part to play. If it is incumbent on the prophet to deliver his message, it is no less incumbent on the people not to turn a deaf ear. It is even more incumbent on them not to make the spiritual climate of their society so adverse to creativity that the life will have been crushed out of the prophet's potential message before he has had a chance of delivering it.

To give a fair chance to potential creativity is a matter of life and death for any society. This is all-important, because the outstanding creative ability of a fairly small percentage of the population is mankind's ultimate capital asset, and the only one with which Man has been endowed. The Creator has withheld from Man the shark's teeth, the bird's wings, the elephant's trunk, and the hound's or horse's racing feet. The creative power planted in a minority of mankind has to do duty for all the marvelous physical assets that are built into every specimen of Man's non-human fellow creatures. If society fails to make the most of this one human asset, or if, worse still, it perversely sets itself to stifle it, Man is throwing away his birthright of being the lord of creation and is condemning himself to be, instead, the least effective species on the face of this planet.

Whether potential creative ability is to take effect or not in a particular society is a question that will be determined by the character of that society's institutions, attitudes, and ideals. Potential creative ability can be stifled, stunted, and stultified by the prevalence in society of adverse attitudes of mind and habits of behavior.

What treatment is creative ability receiving in our Western World, and particularly in America? There are two present-day adverse forces that are conspicuously deadly to creativity. One of these is a wrong-headed conception of the function of democracy. The other is an excessive anxiety to conserve vested interests, especially the vested interest in acquired wealth.

WHAT is the proper function of democracy? True democracy stands for giving an equal opportunity to individuals for developing their unequal capacities. In a democratic society which does give every individual his fair chance, it is obviously the outstandingly able individual's moral duty to make a return to society by using his unfettered ability in a public-spirited way and not just for selfish personal purposes. But society, on its side, has a moral duty to ensure that the individual's potential ability is given free play. If, on the contrary, society sets itself to neutralize outstanding ability, it will have failed in its duty to its members, and it will bring upon itself a retribution for which it will have only itself to blame. This is why the difference between a right and a wrong-headed interpretation of the requirements of democracy is a matter of crucial importance in the decision of a society s destiny.

There is at least one current notion about democracy that is wrong-headed to the point of being disastrously perverse. This perverse notion is that to have been born with an exceptionally large endowment of innate ability is tantamount to having committed a large pre-natal offense against society. It is looked upon as being an offense because, according to this wrong-headed view of democracy, inequalities of any and every kind are undemocratic. The gifted child is an offender, as well as the unscrupulous adult who has made a fortune at his neighbors' expense by taking some morally illegitimate economic advantage of them. All offenders, of every kind, against democracy must be put down indiscriminately according to this misguided perversion of the true democratic faith.

There have been symptoms of this unfortunate attitude in the policy pursued by some of the local educational authorities in Britain since the Second World War. From their ultra-egalitarian point of view, the clever child is looked askance at as a kind of capitalist. His offense seems the more heinous because of its precocity, and the fact that the child's capital asset is his God-given ability and not any inherited or acquired hoard of material goods is not counted to him for righteousness. He possesses an advantage over his fellows, and this is enough to condemn him, without regard to the nature of the advantage that is in question.

It ought to be easier for American educational authorities to avoid making this intellectual and moral mistake, since, in America, capitalists are not disapproved of. If the child were a literal grown-up capitalist, taking advantage of an economic pull to beggar his neighbor, he would not only be tolerated but would probably also be admired, and public opinion would be reluctant to empower the authorities to curb his activities. Unfortunately for the able American child, "egg-head" is as damning a word in America as "capitalist" is in the British welfare state; and I suspect that the able child fares perhaps still worse in America than he does in Britain.

If the educational policy of the English-speaking countries does persist in this course, our prospects will be unpromising. The clever child is apt to be unpopular with his contemporaries anyway. His presence among them raises the sights for the standard of endeavor and achievement. This is, of course, one of the many useful services that the outstandingly able individual performs for his society at every stage of his career; but its usefulness will not appease the natural resentment of his duller or lazier neighbors. In so far as the public authorities intervene between the outstanding minority and the run-of-the-mill majority at the school age, they ought to make it their concern to protect the able child, not to penalize him. He is entitled to protection as a matter of sheer social justice; and to do him justice happens to be also in the public interest, because his ability is a public asset for the community as well as a private one for the child himself. The public authorities are therefore committing a two-fold breach of their public duty if, instead of fostering ability, they deliberately discourage it.

In a child, ability can be discouraged easily; for children are even more sensitive to hostile public opinion than adults are, and are even readier to purchase, at almost any price, the toleration that is an egalitarian-minded society's alluring reward for poor-spirited conformity. The price, however, is likely to be a prohibitively high one, not only for the frustrated individual himself but for his stepmotherly society. Society will have put itself in danger, not just of throwing away a precious asset, but of saddling itself with a formidable liability. When creative ability is thwarted, it will not be extinguished; it is more likely to be given an anti-social turn. The frustrated able child is likely to grow up with a conscious or unconscious resentment against the society that has done him an irreparable injustice, and his repressed ability may be diverted from creation to retaliation. If and when this happens, it is likely to be a tragedy for the frustrated individual and for the repressive society alike. And it will have been the society, not the individual, that has been to blame for this obstruction of God's or Nature's purpose.

This educational tragedy is an unnecessary one. It is shown to be unnecessary by the example of countries in whose educational system outstanding ability is honored, encouraged, and aided. This roll of honor includes countries with the most diverse social and cultural traditions. Scotland, Germany, and Confucian China all stand high on the list. I should guess that Communist China has remained true topre-Communist Chinese tradition in this all-important point. I should also guess that Communist Russia has maintained those high Continental European standards of education that pre-Communist Russia acquired from Germany and France after Peter the Great had opened Russia's doors to an influx of Western civilization.

A contemporary instance of enthusiasm for giving ability its chance is presented by present-day Indonesia. Here is a relatively poor and ill-equipped country that is making heroic efforts to develop education. This spirit will put to shame a visitor to Indonesia from most English-speaking countries except, perhaps, Scotland. This shame ought to inspire us to make at least as good a use of our far greater educational facilities.

IF a misguided egalitarianism is one of the present-day menaces, in most English-speaking countries, to the fostering of creative ability, another menace to this is a benighted conservatism. Creation is a disturbing force in society because it is a constructive one. It upsets the old order in the act of building a new one. This activity is salutary for society. It is, indeed, essential for the maintenance of society's health; for the one thing that is certain about human affairs is that they are perpetually on the move, and the work of creative spirits is what gives society a chance of directing its inevitable movement along constructive instead of destructive lines. A creative spirit works like yeast in dough. But this valuable social service is condemned as high treason in a society where the powers that be have set themselves to stop life's tide from flowing.

This enterprise is foredoomed to failure. The classic illustration of this historical truth is the internal social history of Japan during her two hundred years and more of self-imposed insulation from the rest of the world. The regime in Japan that initiated and maintained this policy did all that a combination of ingenuity with ruthlessness could do to keep Japanese life frozen in every field of activity. In Japan under this dispensation, the penalty for most kinds of creativity was death. Yet the experience of two centuries demonstrated that this policy was inherently incapable of succeeding. Long before Commodore Perry first cast anchor in Yedo Bay, an immense internal revolution had taken place in the mobile depths of Japanese life below the frozen surface. Wealth, and with it the reality of power, had flowed irresistibly from the pockets of the feudal lords and their retainers into the pockets of the unobtrusive but irrepressible business men. There would surely have been a social revolution in Japan before the end of the nineteenth century, even if the West had never rapped upon her door.

The Tokugawa regime in Japan might possibly have saved itself by mending its ways in good time if it had ever heard of King Canute's ocular demonstration of the impossibility of stopping the tide by uttering a word of command. In present-day America the story is familiar, and it would profit her now to take it to heart. In presentday America, so it looks to me, the affluent majority is striving desperately to arrest the irresistible tide of change. It is attempting this impossible task because it is bent on conserving the social and economic system under which this comfortable affluence has been acquired. With this unattainable aim in view, American public opinion today is putting an enormously high premium on social conformity; and this attempt to standardize people's behavior in adult life is as discouraging to creative ability and initiative as the educational policy of egalitarianism in childhood.

Egalitarianism and conservatism work together against creativity, and, in combination, they mount up to a formidable repressive force. Among American critics of the present-day American way of life, it is a commonplace nowadays to lament that the conventionally approved career for an American born into the affluent majority of the American people is to make money as the employee of a business corporation within the rigid framework of the existing social and economic order. This dismal picture has been painted so brilliantly by American hands that a foreign observer has nothing to add to it.

The foreign observer will, however, join the chorus of American critics in testifying that this is not the kind of attitude and ideal that America needs in her present crisis. If this new concept of Americanism were the true one, the pioneers, the founding fathers, and the original settlers would all deserve to be prosecuted and condemned posthumously by the Congressional committee on un-American activities. The alternative possibility is that the new concept stands condemned in the light of the historic one; and this is surely the truth. America rose to greatness as a revolutionary community, following the lead of creative leaders who welcomed and initiated timely and constructive changes, instead of wincing at the prospect of them. In the course of not quite two centuries, the American Revolution has become world-wide. The shot fired in April 1775 has been "heard around the world" with a vengeance. It has waked up the whole human race. The Revolution is proceeding on a world-wide scale today, and a revolutionary world-leadership is what is now needed. It is ironic and tragic that, in an age in which the whole world has come to be inspired by the original and authentic spirit of Americanism, America herself should have turned her back on this, and should have become the arch-conservative power in the world after having made history as the arch-revolutionary one.

What America surely needs now is a return to those original ideals that have been the sources of her greatness. The ideals of "the organization man" would have been abhorrent to the original settlers, the founding fathers, and the pioneers alike. The economic goal proposed in the Virginia Declaration of Rights is not "affluence"; it is "frugality." The pioneers were not primarily concerned with money-making; if they had been, they could never have achieved what they did. America's need, and the world's need, today is a new burst of American pioneering, and this time not just within the confines of a single continent but all around the globe.

American manifest destiny in the next chapter of her history is to help the indigent majority of mankind to struggle upwards towards a better life than it has ever dreamed of in the past. The spirit that is needed for embarking on this mission is the spirit of the nineteenthcentury American Christian missionaries. If this spirit is to prevail, America must treasure and foster all the creative ability that she has in her.

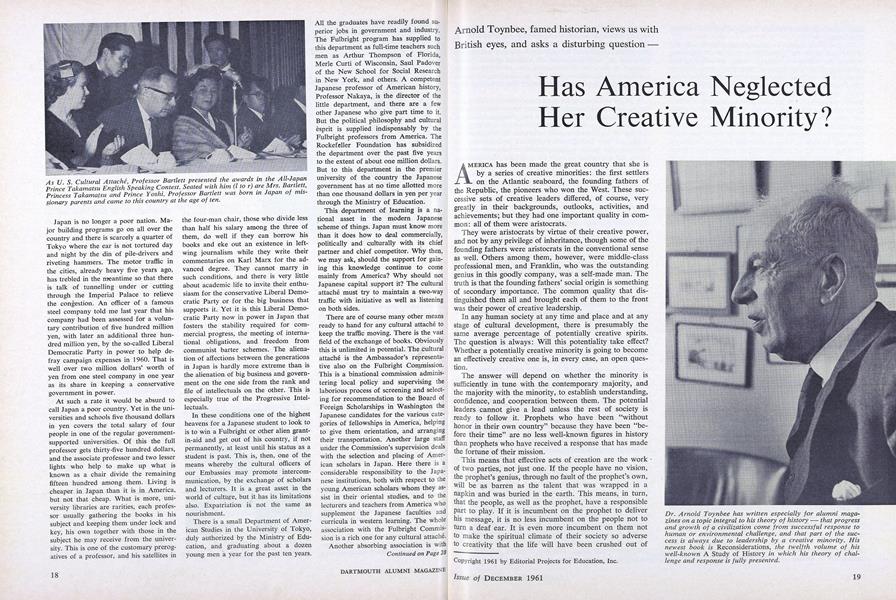

Dr. Arnold Toynbee has written especially for alumni magazines on a topic integral to his theory of history - that progressand growth of a civilization come from successful response tohuman or environmental challenge, and that part of the success is always due to leadership by a creative minority. Hisnewest book is Reconsiderations, the twelfth volume of hiswell-known A Study of History in which his theory of challenge and response is fully presented.

Copyright 1961 by Editorial Projects for Education, Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCULTURAL CATALYSIS

December 1961 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Feature

Feature30,000 Dartmouth Men Are Her Friendsand Problems

December 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

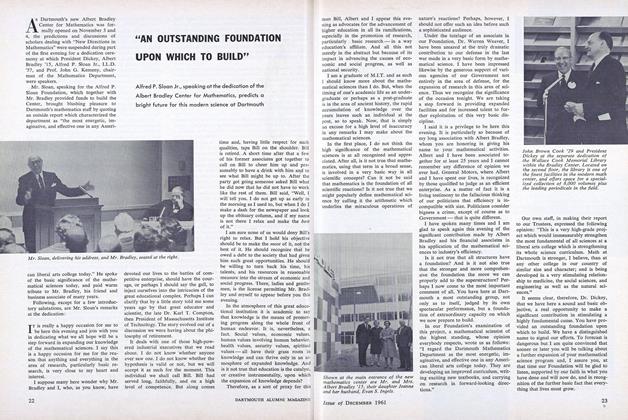

Feature"AN OUTSTANDING FOUNDATION UPON WHICH TO BUILD"

December 1961 -

Class Notes

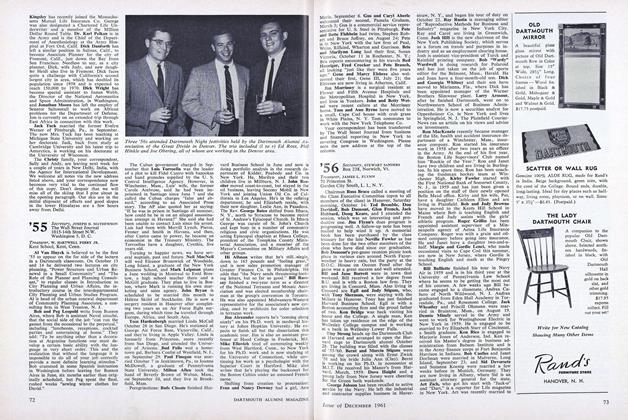

Class Notes1956

December 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, JAMES L. FLYNN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1961 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HENRY S. EMBREE, JOHN F. RICH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1961 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON, JAMES B. GODFREY

Features

-

Feature

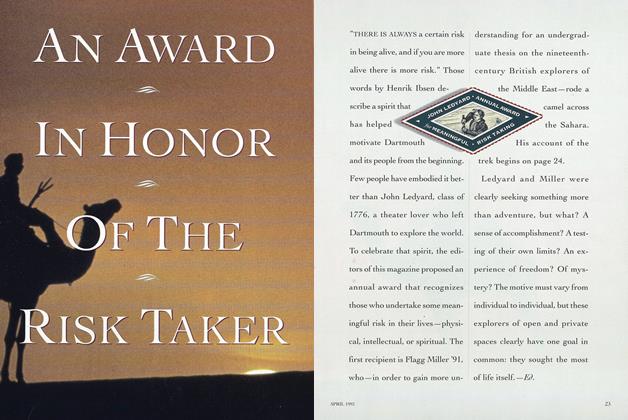

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

APRIL 1992 -

Feature

FeatureBRUCE SACERDOTE '90

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

Nov/Dec 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeatureThe Book That Was Banned in Hanover

JANUARY 1999 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow to Avoid Being Taken to the Cleaners by Your Ex

Sept/Oct 2001 By STACY D. PHILLIPS ’80