EVEN the most casual perusal of the summary page reveals that the Big Green winter teams are in general destined for mediocre seasons. Perhaps this past Saturday (January 14) was the low point of the winter, for all six of the varsity teams suffered defeats and only three of the six freshman teams emerged victorious. On this "Black Saturday" the basketball team dropped a league contest to Columbia, the hockey team was walloped by Harvard, the squash and wrestling teams lost to the Crimson, as did the swimmers, and the track team was edged by Cornell. At the freshman level the basketball team defeated St. Michael's, the swimming team upset Harvard, and the track team edged Cornell. The hockey team, however, lost to Harvard, as did the wrestling and squash teams. So in a total of eight varsity and freshman encounters with Harvard teams, the Big Green managed to emerge with only one victory.

No league championships appear in sight for Dartmouth this winter, with the strongest team apparently the Big Green varsity swimming squad. Dartmouth's track fortunes appear to be gaining with a better-than-average varsity and a fine freshman squad, but squash is way down, basketball is re-building and hockey may be on the way down. The wrestling team prospects are only fair, although the sport is still in the growing stages.

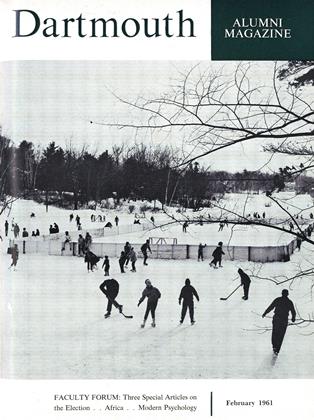

The Big Green skiers have been competing individually and generally doing well in Eastern meets, but they will not see action as a unit until the Dartmouth Winter Carnival early this month opens the carnival circuit. The Indians have a strong ski team but Middlebury again looks better and Western competition grows stronger on the national level.

This month we'd like to use these columns for a few observations on the cyclical nature of collegiate sports and to discuss some of the changes that seem discernible of late in intercollegiate athletics.

Just two years ago at this time Dartmouth was riding the crest of the wave. Alumni were feting the Big Green Ivy League championship football team at a January Alumni Council banquet. The basketball and hockey teams were headed for League championships and the varsity ski team went on to sweep all carnival meets and capture the NCAA Championship cup. This year the basketball team has only two wins in eight games, the hockey team has won two of six contests, the squash team has but one win in five outings, while the varsity swimmers have a 2-1 record, the track team has split even in dual meet competition, and the varsity wrestling squad has dropped the opener to Harvard 19-9.

There is nothing alarming about these results, for any study of Dartmouth and Ivy League records indicates that teams in all sports have their ups and downs and that few colleges, at least in tight Ivy competition, have been able to dominate for any length of time. Yale, of course, has consistently produced one of the finest swimming teams in the nation, but this ascendancy is now threatened by Harvard in the East and a few midwestern and far western universities. Dartmouth has likewise been noted for her outstanding skiing and hockey teams, but in recent years Middlebury in the East and Colorado and Denver in the West have moved into Dartmouth's class in skiing, while in hockey Harvard, R.P.I., Boston College, Minnesota and Colorado are on a par or, certainly this winter, have better teams.

This sort of cyclical swing in intercollegiate sports is a healthy one and few will dispute that without it much of the interest in intercollegiate competition would evaporate.

Much more serious, however, than the seasonal ups and downs of teams or sports is the recent trend away from formally organized team sports in favor of either informal competition or intramural athletics. One can quickly point to Chicago, Fordham and just this past month the University of Denver, who have dropped football from their athletic programs. Smaller colleges have gone further in dropping or seriously curtailing sports. The reasons for such actions have almost invariably been those of finances.

There is little doubt that finances in intercollegiate athletics are a problem. The lush days when the football team produced enough income to carry the entire sports program are over on most college campuses. Dartmouth for some years was able to finance all its formal athletics from football receipts and in some good years even produce a surplus. This past year (1959-1960) income fell short of expenses for the DCAC by some $191,000 and it seems inevitable that these expenses will mount as general operating costs spiral upward.

Football, of course, has been and will continue to be a major source of income. Despite nationwide studies indicating attendance increases in college football, this is not the case in the Ivy League where attendance has slumped. There seems little doubt that the televising of college football on a nationwide scale, coupled with the rapid growth of interest in professional football, has started to cut severely into the college gate receipts.

But finances are not the basic problem. Most colleges today consider formal athletics a vital, necessary and integral part of the college program. It is just as necessary to maintain a sound sports program as it is to maintain an effective Mathematics Department and the money invested in sports is as important as that spent for other aspects of the College program.

The really disturbing trend in collegiate sports is one which has been noted in other areas of extracurricular activities - namely, a sharp decline in genuine student interest and desire. This trend is most keenly felt in athletics because of all activities they are the most regimented and demanding.

At Dartmouth, for example, the past decade has seen a marked swing from the more formal type of sports to the informal sport programs. The Rowing Club, the Sailing Club, Rugby, sports car racing, the more informal D.O.C. programs, and the formation of an informal town-and-gown hockey team (The Storm Kings) have opened new outlets for students who might otherwise participate on regular DCAC-sponsored teams. Some of these activities have, of course, grown more formalized as they develop. Crew, for example, came back into prominence in the early 1950's as a loosely-knit organization along club lines with Dean Thaddeus Seymour as a parttime coach. Today it is fully organized with a full-time head coach and rigger, and receives some financial support from the College. Rugby, on the other hand, is largely unorganized and is conducted chiefly by the student members of the club. Some of its players are men who gave up football, others were prospective football players who preferred the informality of rugby.

The Dartmouth coaches and indeed those at the other Ivy institutions have been frankly disturbed by the number of high school athletes who either do not try out for the squads, or who give up after a very limited trial.

It is difficult to track down all the factors for this increasing attrition rate in intercollegiate athletic competitors, but there are certain elements readily observable in Hanover,

First, the opening up of rapid transportation coupled with the enlarged social opportunities of today's students has vastly increased the social life at the College. The Dartmouth of even a decade ago saw far fewer "dates" on campus, and the major college weekends - Fall Houseparties, Carnival and Green Key - are now preceded by a series of smaller weekends. When this is coupled with the increasing number of student cars on campus, making possible easy weekend trips to women's colleges throughout the East, it is easy to see why many potential athletes prefer to be free for social life rather than fully committed to sports.

More impelling, of course, is the increased academic pressures encountered by today's students. The boys attending Dartmouth realize that their major concern is formal education and the academic program at Dartmouth today is far more challenging and demanding than that faced by any alumnus. Many excellent athletes simply give up formal competition during or at the end of the freshman year so they can have more time for studies.

A third factor, which is more difficult to pinpoint or explain precisely, is, we believe, the increased pressures and demands placed on a boy by intercollegiate athletics. Football, hockey, basketball, baseball and even swimming and squash are more complex and the competition is much greater than it was in the past. A greater degree of initial skill and training and generally a more rigorous and demanding schedule are called for in modern sports. Consequently, we believe, far fewer boys are willing to pay the stiff price in time and effort required to make the team.

Gone are the days when a big, awkward 230-pound lad who straggled onto the campus was collared by the football coach and before he knew what was happening found himself in a football suit on the practice field. Today's coaches in many sports can reel off facts and figures on the players who will comprise their freshman squads before these lads have even matriculated.

"You can't win without the horses," shout the coaches, and so the complex and much-abused enrollment system came into being, designed to assure that each institution received a fair share of the "horses." This, in turn, has discouraged some degree of participation in intercollegiate athletics, for most boys know that unless a coach or "enrollment" worker has talked with them their chances for making a team are rather limited.

But what does all this mean in terms of the future of intercollegiate athletics and competition? Is it possible, as recent Faculty Committees on Athletics at Dartmouth have hinted, that intercollegiate athletics as we know it may be on the way out?

There is little evidence to substantiate this, but there is some reasonable evidence, at least at Dartmouth, that fewer students are seriously interested in staying with formal sports and that even student spectator interest is falling off. However, there is no reason to believe that the formal sports program here will be curtailed; indeed it could well be expanded in the immediate future.

In the longer view the picture becomes less clear. Any change away from the more formal sports programs will probably be made not by any single institution but by conference groups such as the Ivy League. The Ivy presidents today are clearly on record as to their firm belief in the importance of intercollegiate competition.

What is certain is that as all colleges and universities move into the coming decade, officials will be closely scrutinizing the athletic programs at their own and at sister institutions. The relationship of formal athletics to the more informal type, either on a club or intramural basis, will be closely studied.

Signs of change in college athletics are all about us today. No one can predict what these changes may be or when or how they will occur. It is to be hoped that whatever happens, formal intercollegiate competition will not disappear from the college scene.

Wrestling coach Bill Craver gives a pointer to senior Hop Holmberg and All-New England wrestler Ellie Torbert (r), a junior. Freshman coach Whitey Burnham looks on.

The Big Green second line of Dave Leighton (16), Warren Loomis (8) and John Phelan (5) closes in on the Yale goal during an Ivy League contest in Hanover. Leighton's shot was turned aside, but seconds later Phelan fired the puck into the nets. Yale won, 5-3.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dollop of Yankee Talk

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

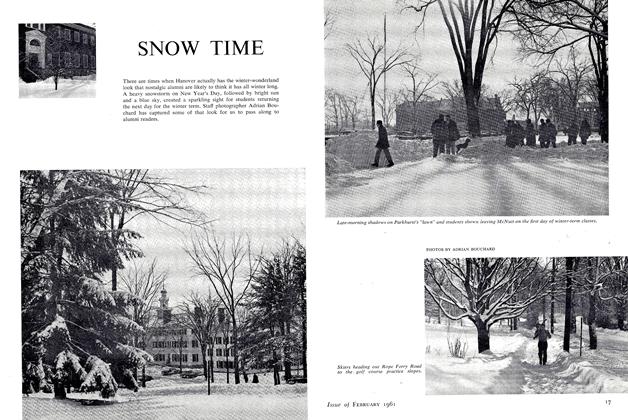

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleProblems of Land Development in the New African Nations

February 1961 By BARRY N. FLOYD,