ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF GEOGRAPHY

ABOUT nineteen hundred years ago, an astute Roman named Pliny the Elder observed: "Out of Africa there is always something new." As one reads the news dispatches which are pouring out of Africa today, one wonders what the prophetic Pliny would think if he could see the African continent at the present stage of its troubled history. All he ever knew of Africa was the Mediterranean littoral to the north. The heart of Africa was enscribed terraincognita across all the oecumenical maps of his day and embellished with legendary monsters. As Jonathan Swift wrote later: "So Geographers in Afric-maps, With Savage Pictures fill their Gaps, And o'er uninhabitable downs, Place Elephants for want of towns."

In the twentieth century Africa has, to be sure, revealed most of her geographical secrets. Her mountains have been explored, her lakes charted, rivers mapped and her peoples located. But still the search continues, not merely for stubborn undiscovered features but for new ways of utilizing the known resources in the service of man. Until recently it was the European, colonial man; now it is the African, aspiring to be master of his own destiny in the newly independent states of Africa.

The significance of agricultural development schemes in Africa can best be judged then in the light of the complex and often recalcitrant problems of political development throughout this continent today. The new leaders of Africa must not forget that, after all the flag waving and excited cries of Freedom are over, there remains the colossal task of maintaining and eventually raising the living standards of their peoples. This means, as much as anything, improving and intensifying agricultural methods and productivity so that the rapidly increasing numbers of Africans may be adequately nourished, labor released for other forms of economic endeavor, and the feverish campaign promises ultimately made good. The director of an inter-racial community in Southern Rhodesia once said: "The mealie [corn plant] in its growth pays scant attention to the pigment of the ploughman's skin." In other words, achieving emancipation from the "colonial yoke" and sending European settlers packing will not, ipso facto, make the crops grow better in celebration. Again, it was Swift who wrote: "Whoever could make two ears of corn or two blades of grass to grow upon a spot of ground where only one grew before would deserve better of mankind and do more essential service to his country than the whole race of politicians put together."

Schemes dealing with the improvement of agriculture are, therefore, among the most important of African programs for economic development. This opinion is strengthened by the observation that the vast majority of Africans are still engaged in tilling the soil or in animal husbandry. It has been estimated that no less than 75% of Africa's 230 million inhabitants are engaged in agriculture, the highest proportion of any continent, although Asia with 70% and a much higher population base comes a close second.1 Africa's agricultural productivity is, however, probably the lowest in the world, whether measured as production per person or per acre. Clearly, the future economic stability and social welfare of the rural African depends in large measure upon the intelligent handling of land development schemes. The purpose of these schemes is, above all, to raise the African peasant above the "meagerness and meanness of mere existence."2

We might remind ourselves at this point that the problems of agriculture in Africa are highly similar to those faced by primitive farmers within the low latitudes of America and Asia as well. Essentially these problems derive, as Professor Frankel of Oxford has observed, from "the clash between the functional forces of modern industrialization and the rapidly disintegrating indigenous economies of communities governed by forms of social organization unable to yield the living standards being demanded by all the peoples of the world."3 Here are no problems unique to Africa, then, even if some of the programs which have been initiated by, for example, the French, Belgians, British and Portuguese are in many respects outstanding ones.

Yet certain assumptions of the European-guided betterment schemes in Africa require challenging. It has been far too commonly assumed that to achieve advances in African agriculture, it is necessary to sweep away completely all indigenous land use customs and to substitute in their place western traditions of tenure or land ownership and European techniques of so-called scientific, modern agriculture. Even after the groundnut debacle in Tanganyika a decade ago, the superior assumption persists that European agricultural methods can be transplanted virtually without modification into the African milieu. The realization that the physical and cultural geographic environments of Europe and Africa are grossly dissimilar still seems not to have penetrated the thinking of many western-trained land use planners in Africa. My thesis is that nothing could be more dangerous for the African farmer than if his old ways were to be uprooted and if strange innovations were to be introduced almost overnight.

One would contend instead that, more and more in the future, agronomists will be required to take the feelings of the African as a human being, not as an agricultural statistic, into account. Furthermore, many of the time-honored and tested native methods of farming may have relevancy for the changes which are being planned. We cannot be so presumptuous as to claim that there is nothing worth redeeming or rescuing from traditional tribal tenure or agricultural systems. Changes are necessary, to be sure. The question is: under what terms and by what methods should innovations be introduced? Agricultural planners must conserve good will as well as the soil.

Specifically, there are a number of land development problems in tropical Africa which require urgent resolution. An outstanding one concerns the issue of subsistence farming through the traditional techniques of shifting cultivation or "bush fallowing." Under this primitive method of crop production, small clearings are made in the rainforest or wooded savanna (bush) areas, using axes to fell the trees and fire to burn off the undergrowth. The land is then planted to staple crops (manioc, yams, corn, sorghums, millets or rice) through broadcasting the seeds or planting roots. An occasional weeding may be given the patch of cultivated plants but no other attention is paid to the land until harvest time. The cycle is repeated three or four times until the fertility of the tropical redearth soils has been depleted, after which the clearing is abandoned and allowed to revert to a second growth of natural vegetation. In this manner, under the conditions of a natural fallow, the structure and productivity of the latersolic soils are slowly restored. Meanwhile, fresh clearings have been opened up elsewhere and the pattern of nomadic farming is continued.

This crude yet ubiquitous technique of subsistence cultivation was much criticized by colonial authorities during the early years of Euro-African contacts. It was considered exploitative and wasteful of natural resources. In later years, however, it was recognized that this Bantu system of farming was, in effect, quite a sensible adaptation to the difficult physical environment on the part of primitive peoples with limited attitudes, objectives and technical abilities vis à vis food production. Indeed, as Lord Hailey was to write in his authoritative African Survey, shifting cultivation is "less a device of barbarism than a concession to the character of the soil"4 which needs long periods of rest for regeneration.

Unfortunately, shifting cultivation, under average conditions, can support only about twenty to twenty-live persons per square mile, if the land is to remain in good heart. Yet one of the great dilemmas in many parts of Africa today is that of a steadily increasing pressure of population upon finite, indeed deteriorating agricultural land.

Permanent cultivation and continual cropping have been encouraged for some years in the Rhodesias, Overseas Portugal, British East Africa and in certain West African states. The resultant tendency towards soil degradation is being combatted by promoting crop rotations (including a grass or legume cover), heavy applications of organic manures and composts, green manuring, and chemical fertilizers. In Southern Africa, the concept of ley farming is widely held to be the key to the maintenance of soil productivity, a ley being a grass break in the cropping program. It is claimed that a dense mat of fertilized grasses, kept in place for two or three years, can accomplish the same regeneration of soils as natural bush fallow, but in a fraction of the time. Results of experiments at research stations have tended to support such a land use program.

The question arises however: have not agronomists again overemphasized the technical aspects of the problem and overlooked or disregarded the human element? From personal observations in Southern Rhodesia, I believe it highly doubtful that Africans will adopt the practices of ley farming voluntarily. Fanning to them is still necessary for human survival; all efforts must be put into growing foodstuffs for humans, not the cultivation of grasses. All theoretical talk concerning the building up of soil structure and fertility is outweighed by the more urgent and immediate problem of empty bellies to be filled. It is almost axiomatic to state that the willingness of an African cultivator to adopt new ideas in agriculture is conditioned by the tangible benefits which he expects to receive for an extra expenditure of labor in a relatively short space of time.

The fertilization of grasses is also an unacceptable proposition to primitive farmers; indeed, the entire question of fertilizing the soil is fraught with difficulties. The handling of animal waste matter was thought by some tribes to induce sterility. It is difficult to make good farm manure in tropical Africa due to climatic factors; seldom does the manure produced resemble the moist, rich muck pile of a Corn Belt farmer in the U.S.A. Manure requires the building of cattle kraals, the feeding of cattle with crop residues and the transferring of materials to and from the fields. All this means a considerable expenditure of physical effort on the part of the African farmer. He naturally inquires: is it worth it? It might also be observed that animals really add nothing to soil fertility apart from breaking down plant nutrients and transferring them from one place to another, in this case from the grazing areas to the crop lands. This tends to intensify the impoverishment of the pasture lands which are themselves in great need of upgrading. Chemical fertilizers (NPK) may certainly improve the productive capacity of soils but they are well beyond the purchasing power of the majority of small farmers. Without proper soil analyses, considerable wastages may occur in their indiscriminate application.

Green manuring, i.e., the plowing under of a manure green crop which could be fed to cattle also appears senseless to the average African. While this technique may have proved beneficial in the U.S.A. and Europe, it is a very debatable practice under tropical conditions. A Portuguese agriculturist has claimed that, compared with fallowing, green manuring produces negligible, if not detrimental effects, particularly in soils with poor stucture and light texture. Even though, theoretically and technically, it may be possible to cultivate land continuously within tropical Africa, a great deal of propaganda, persuasion and economic assistance will be necessary to get subsistence farmers to adopt wholeheartedly the necessary measures.

A second aspect of African agricultural development concerns land tenure and the nature of agricultural holdings. An innovation which is being introduced into many parts of Africa is the so-called individual or freehold ownership of land, in contrast to tribal systems of ownership which have been termed communal.

Recent research by social anthropologists, has tended to emphasize the complex nature of tribal land tenure laws and has particularly countered the notion that native systems were strictly communal, with everyone having an equal right in every piece of the tribe's land. While the land may have belonged to the tribe as a whole, and the chief and sub-chiefs or headmen allocated rights to cultivate and harvest (usufructuary rights), in reality a farmer had a security of tenure not unlike that under western forms of land occupance.

It should also be noted that land to the African bears something of a sacred character; rights over land were the most jealously guarded of all rights at one time. There was a mystique associated with man's attachment to the soil. Land was, in fact, not merely a possession but a way of life. As a West African chief has succinctly remarked: "I conceive that land belongs to a vast family of which many are dead, few are living, and countless members are still unborn."5 It is the dynamic heritage from these traditional attitudes of native societies towards the land with which agronomists must reckon today.

There is virtual unanimity on the part of land tenure authorities regarding the need to eradicate one fundamental feature of native land law: the tradition that it is the right of every African male to possess land and to own cattle. Pressure of population and finiteness of land resources will not permit a totally rural economy today. It is also widely agreed that some form of tenurial change is inevitable since, with the breakdown of traditional tribal laws, a great deal of corruption in land allocation under tribal leaders has entered, which is hampering the advancement of agricultural improvements.

With the need to effect tenurial changes has come the perplexing question of which forms of tenure can best meet the demand for more intensive settlement and wiser utilization of the land by Africans. The individual title deed has been promoted in Southern Rhodesia under the Native Land Husbandry Act and in Kenya under the Swynnerton Plan.

This choice of individual tenure is a debatable one made on the basis of several tenuous propositions. It is apparently considered that individual tenure will provide a clean break from decadent tribal laws and give a landholder a greater sense of security, hence a greater incentive to improve his soil by practicing conservation and more intensive farming methods. Pride of ownership, it is claimed, will resolve the problems of land abuse; in the words of a famous English agriculturist of the eighteenth century, Arthur Young: "The magic of property turns sand into gold." The implication is that the absence of a conception of personal ownership of land has retarded the development of African agriculture.

One has only to turn to other areas of Africa to see the fallacy of this argument, areas where export crops have been produced by tribalized Africans who did not possess individual rights when cash-cropping began: coffee in Tanganyika, for example, cacao in Ghana, wattle and maize in Kenya, coffee and cotton in the Congo. The direct economic incentive of a good price for cash crops is often sufficient to encourage improved farming, regardless of the system of tenure.

Individual rather than tribal tenure was introduced into certain areas of the Transkeian territories of the Union of South Africa as long ago as the turn of the century, especially in the district of Keiskammahoek. The history of this tenurial experiment shows that African cultivators have treated their lands in a highly similar manner to those who acquired their land in the traditional way by allocation from the village head. In sum, no modern plans for agrarian development should depend on changes in tenure alone. The political arguments for the granting of individual land rights may well be decisive in the end, but they should be clearly distinguished from attempts to advocate "the magic of property" as the main stimulus to increased agricultural productivity and wiser land use.6

A third problem in the improvement of African land use concerns animal husbandry. The traditional African view towards cattle is quite different from that of the European. This is the so-called "cattle complex" of the African.

In European society cattle are kept simply for the provision of meat, hides, milk and, in a mixed-farming economy, their manure. To Africans these are alien considerations. For them cattle have a social and religious significance. In tribal life cattle were not for sale; indeed, this was a "foreign and reprehensible thought. They could leave the family in life only to bring it a bride. In death they should provide the sacrifice that the spirits demanded."7

A fundamental principle of marriage and family among many Africans concerns the payment of an agreed "bridewealth" of so many cattle to the wife's family. This age-old institution of lobolo is, in spite of much anthropological writing, still widely regarded by Europeans as buying a wife. The transaction is not in the form of a purchase, however, but rather an exchange, "the bride's family losing a reproductive potentiality yet receiving the means to obtain a wife for its own reproductive purposes from another lineage."8 The custom of lobolo was an effective form of insurance or security against marital abuse because a cruel husband would run the risk of losing not only his wife but also his claim for return of the "bridewealth." These attitudes are a strong factor in any plans for livestock improvement through upgrading by controlled breeding, culling and disposal of surplus stock, and pasture management schemes.

Compulsory destocking of cattle has been the least palata ble aspect of European-inspired land reforms in Africa. It has led to marked resentment and, in places, to an open hostility between animal husbandry officials and native pastoralists. A reduction in numbers is an essentially negative approach towards the problems of cattle rearing and should be replaced by more positive efforts aimed at improving the carrying capacity of the grazing areas. Most African cattle represent a vast reservoir of indigenous blood, genetically superior to their environment. All possible measures should be applied to improve grazing lands through rotation of paddocks, the introduction of improved grasses and the growing of special fodder crops in the grazing areas for offseason, supplementary feeding. Good prices should also be offered for disposable cattle at regulated auction sales. As with crop production, a cash incentive may be sufficient to bring about the necessary revision of attitudes towards cattle, if Africans are to improve their standards of nutrition and ultimately their levels of living.

In sum, there are, in effect, two main schools of thought regarding the advancement of African agriculture. We may label them the "revolutionary" and the "traditionalist." The revolutionary school is confident that the problems of land development in Africa can be solved only by making a complete sweep of customary native institutions and methods of cropping, replacing them with European or western-styled agronomic techniques based essentially on continual cultivation of the soil and ranching for beef. Reflected in this school is an inherent belief in the superiority of western knowledge and experience in rural land use, even under the different environmental and socio-economic conditions of Africa.

The traditionalist school, on the other hand, is noted for its defense of native techniques of agriculture and its emphasis on the vast fund of African knowledge concerning variations in soil capabilities and other physical factors which has been accumulated over centuries of adjustment to difficult environments. An almost reverential attitude to established agricultural practices is often apparent in this approach. Here are the words of a Portuguese agronomist:

Soil and water conservation has been taught to these whitebearded farmers and to their grandchildren by the university oftime and hardship; it is a psychological self-tuition, present in every race independently of its standard of civilization.... The scientist with a vast field of research in front of him cannot absolutely disregard principles established by thousands of years of practical experience.9

My purpose in this essay has been to suggest the importance of blending both modern scientific concepts concerning land development and the traditional knowledge and cultural heritage of the African farmer. I believe agricultural planners in Africa must aim at an amalgam of both old and new in the field and laboratory sciences of food production.

Quite obviously, no single solution or easy panacea can be found, or should be expected, for meeting the problems of land development in all areas of tropical Africa. It will require the combined cooperation of workers in many disciplines if adequate new systems of making a livelihood from the land are to be developed in the new African nations. We should make a great mistake if we were to look for one staple system of agriculture which could be universally taught and applied in the tropics.

Meanwhile, the dying words of Cecil John Rhodes form a fitting conclusion to this study: "So much to do, so little done.."

1. Walter Goldschmidt (ed.), The United States and Africa (New York, 1958), p.8.

2. President Dickey of Dartmouth College has suggested that the role of a liberal arts college in the U.S.A. is to raise its students above the "meagerness and meanness of mere existence." This phrase is equally relevant in defining the objectives of all betterment schemes in Africa which have, as their goal, the raising of living standards among primitive peoples.

3. S. H. Frankel, The Economic Impact on Under-DevelopedSocieties: Essays on International Investment and Social Change (Oxford, 1953), p. (V).

4. Lord Hailey, An African Survey (London, 1938), p. 1.

5. Quoted by C. K. Meek, Land, Law and Custom in the Colonies (London, 1949).

6. L. P. Mair, Studies in Applied Anthropology (London, 1957),

7. Charles Bullock, The Mashona and the Matabele (Cape Town, 1950), p. 99.

8. Southern Rhodesia, Native Affairs Dept. (Information Branch), The Africans of Southern Rhodesia (Salisbury, 1958), p. 8.

9. Armando Salbary, "Some Aspects of Soil Conservation in Mozambique," Sols africains, II (1953), p. 323.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dollop of Yankee Talk

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

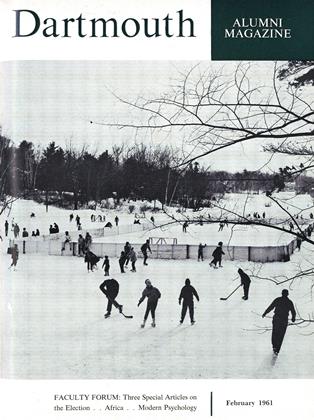

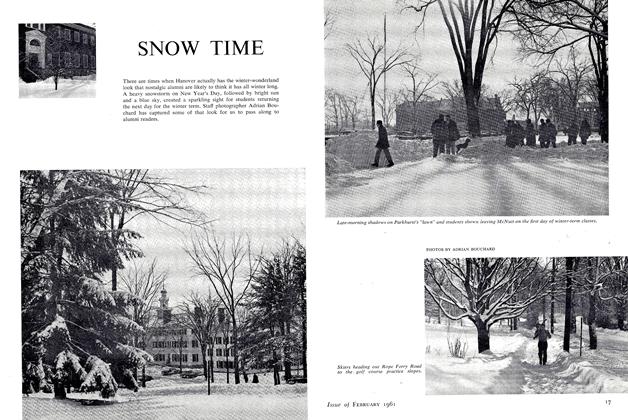

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleSome Thoughts on the Election

February 1961 By ALAN FIELLIN,