WHEN it appeared two years ago, a rousing salt-water novel by Charles F. Haywood '25, Eastward the Sea (Lynn, Mass.: Jackson and Phillips, 1959), was praised for the authenticity of its historical detail and for the author's knowledge of the speech and customs of old Salem and Marblehead in the days of square-rigger sailing ships.

The book's virtues on this score were no accident, because Mr. Haywood, a Boston attorney who writes as an avocation, had dug assiduously into the social history of the period in order to get his details right. He became especially fascinated with everyday figures of speech, many drawn from ships and the sea, and this led to his compiling what he calls his "Yankee Dictionary." The speech of Marbleheaders and other Massachusetts coastal inhabitants is still salted with some of the expressions in everyday use a century and a half ago.

Many of Mr. Haywood's definitions of Yankee talk appeared as a regular feature in The Boston Globe. At the request of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE he has made a selection of definitions from the hundreds he has written, and we present them here with the thought that Dartmouth men will find them not only good reading but also fascinating commentary on life in the early 1800's:

Afoot or Ahossback: another one of the "He don't know" expressions. When a Yankee says "He don't know whether he's afoot or ahossback," he means that the person to whom reference is made is in a bemused and bepuzzled state, to wit, a quandary. Or perhaps he means that the fellow lacks sufficient mental acuity to know where he is going or how. Note carefully that any one who lets the sound of the letter "r" creep into this expression is no Yankee.

Black as the King of Hell's Riding Boots: the old rooster who first said this might have said "black as your hat" or "black as the ace of spades." And it is doubtless true that he had never seen the Old Nick, nor did he have any way of knowing whether he owned a pair of riding boots. Although based on inaccurate information and having the fault of an undue prolixity, the expression nevertheless gained currency among those who feel that unadorned similes are very tedious indeed.

Bought His Thumb: This one belongs with the remarks about sugar stretched out with sand, well watered milk, sawdust in the coffee, and wooden nutmegs. When an old timer said "I bought his thumb" he meant that he suspicioned the storekeeper rested his thumb on the scales when weighing the meat or cheese or turnips, a procedure good for two or three more ounces on the dial and a few cents more on the price.

Church Stick: in Colonial days when the minister who could deal with sin and damnation in less than an hour was a rarity, many church-goers had a tendency to snooze a bit except when the preacher was really making the flames roll up from hell. The deacons took care of this by providing the tithing man with a light staff, on one end of which was a rabbit's foot and on the other a foxtail. He patrolled the aisles, tickled the chin of whomever had fallen asleep, and if the man woke up with an ejaculation inappropriate to the time and place, the tithing man held his finger to his lips to still any unseemly levity.

Hannah Cook: almost nothing is known of this lady, her domicile, family connections, appearance or the time in which she lived. Although the most thorough historical research has revealed no actual facts, it is certain that her abilities must have been meagre and her station in life lowly, since generations of New Englanders have habitually used the expression "It don't amount to Hannah Cook" to indicate that they hold an extremely low opinion of anything.

Cut of His Jib: A nautical phrase that has come ashore; now widely used to mean a man's appearance, manner and way of doing things. When we say of a man we do not "like the cut of his jib," we mean that viewed from a distance he creates an unfavorable impression. In the days of sailing ships, each vessel had minor peculiarities in the arrangement of its canvas and rigging; differences sufficient to make of each ship an individual. A ship master, standing on the quarterdeck with his telescope to his eye, would first try to identify a faraway ship by carefully examining its sails and rigging. The jib, one of the headsails, a triangular canvas easy to pick out at a distance, was one of the first features of a strange ship to be noted. If it was cut in a manner peculiar to the British Navy or the French privateers or the Mediterranean corsairs, the skipper would say "I don't like the cut of her jib" and immediately he would give orders to change his vessel's course so he would not be obliged to have any closer acquaintance with this ominous looking stranger. But if he did like the cut of her jib, he would steer a course to come up with her, bring his ship to and speak to her. Fore topsails aback to check headway, the two captains would bellow news to each other through their speaking trumpets. They might even lay to long enough to swap provisions, do a little trading and let the crews gossip a bit and try their hands at cheating each other in the exchange of the small items a sailor always has in his sea chest.

Daown Bucket: A Marbleheader thus greets a friend. Whether he meets him walking along on a nearby wharf or repairing a motor on some boat out in the harbor, the cry is the same. And the reply is always "up for air." Some think that "daown bucket" originated aboard the fishing vessels as a warning when the men on deck lowered away to those working below. Others claim it is a warning shouted by a housewife when she emptied from an upper bedroom window a receptacle she should have taken out to the backyard. Still others say it comes from the days of the hand fire engines (hand tubs) and is what they shouted to keep time as thirty men worked the "brakes" up and down to pump water to the fire. This is the most likely, since they were bucket or plunger type pumps, pushing water on the down stroke and taking air on the up stroke.

Devil's Dancing Rock: A wide flat stone the size of a table top or larger, worn smooth by glacial action, frequently found in New England pastures or on a little knoll. It was a saying among the old settlers that in the full of the moon anyone who looked sharp might see Old Scratch himself doing a solo dance on such a rock.

Dollop: as much as the cook thinks is right. Down on His Uppers: to be in poor circumstances and suffering a reversal of fortune. The upper is the part of the shoe above the sole, so a man who is down on his uppers is scuffing along with his bare feet practically on the ground, without the money to get his shoes tapped, let alone buy a new pair.

Happy as a Clam at High Tide: the way folks along the Yankee Coast describe a state of contentment, plenitude and security. For a clam, high tide is his time of maximum felicity. He is in his native element, a situation pleasing to every mortal being. The sea which nourishes him covers his lodging place to a depth of at least eight feet, so he need take no thought of how he is to be fed. And he is secure, for not until the tide is low and the long expanse of beach or mud flats glistens wetly in the sun, is the presence of his home beneath the surface betrayed to a man with a clam rake or a predatory animal or bird. Implicit in this expression is the thought that the clam's happiness, like that of all the rest of us, is but temporary.

Heater Piece: the corner made by two streets or roads that intersect at an acute angle, so-called because its outline resembles that of a flatiron. Farmers sometimes call a field of that shape "the heater piece." The famous Flatiron Building in New York was so named by reason of a similar fancy.

Hell Room: when one holds a fellow mortal in very low esteem, the opinion is frequently expressed by the statement, "I wouldn't give him hell room." No one has ever offered to explain what lower apartment might be made available.

Husher: This was the finely worked crochet piece our ancestors fitted over the cover of an earthenware chamber pot so that cloth was interposed between the under side of the cover and the rim. While the vessel was a necessity and the cover highly desirable, a housekeeper possessed of the finer perceptions tried to eliminate the clang of crockery upon crockery that resounded through the house in the still watches of the night when some sleepy user was clumsy in the use of the convenience under the bed. Hence the husher, an article of utility and ornament upon which many a lady of a bygone day lavished hours of careful needlework. Unfortunately specimens are hard to find in our museums.

Jorum: the old term for a Big Drink. "Jorum" might refer,to the mug or the drink itself. Generally the word described hard stuff; a man might order a jorum of rum, but never a jorum of milk.

Long Boat: the largest and most able of a ship's boats, often used for going ashore for firewood or water. In abandoning ship the long boat was the safest and most likely to survive. Old mariners, if about to withdraw from a difficult situation, would say, "I'll take the long boat and go ashore."

Mackerel Sky: a pattern of equally spaced narrow white clouds with blue sky showing in between, not unlike the regular markings on the skin of a mackerel. Those who think they can foretell the weather by the various cloud formations and other signs say "Mackerel sky, never long wet, never long dry." According to Mark Twain "never long wet, never long dry" is a safe prediction at any time in these parts. Brought up in the middle west, he vainly tried to get used to the weather here, but he gave up and coined his immortal epigram "If you don't like New England weather, just wait a minute." He continued to reside here, however.

Nantucket Sleigh Ride: The term was made famous by the Nantucket Islanders, who, in the first half of the 19th century, made fortunes from whales caught in the far oceans of the world. When the masthead lookout sighted the spouting of a whale, he shouted "Thar she blows," the boats were lowered away and rowed to the spot, the man in the bow of the first boat to reach the whale threw his harpoon, and when it sank into the creature, things began to happen fast. The whale might "sound," that is, he might go deep. Or he might thrash about on the surface, smashing the whaleboat. Or he might run for it, in which case the harpooner would let out all the line in his tubs, take a double bight around the loggerhead and let the whale tow the boat at a wild speed until he was tired out. The oarsmen would rest on their oars, while the boat went through the water at terrific speed, shipping spray over the bow and leaving a boiling wake astern. Sometimes the boat caught a wave and foundered, or took aboard so much water that the line had to be cut, but generally the "Nantucket sleigh ride" ended when the whale wore himself out many miles away from the ship. Then the whaleboat closed in for the kill. The whale might react savagely, but the Nantucketers never hesitated, for their watchword was "a dead whale or a stove boat."

Orts: an old fashioned word for table scraps. Shakespeare has a line; "Let him have time a beggar's orts to crave." This word, like its synonym "swill," has gradually died out as folks have sought more refinement of speech through the use of more syllables, and the term "garbage" is now more commonly accepted, although the truly cultured achieve the ultimate in polysyllabic respectability with the expression "culinary residuum."

Parsnips: the Yankees say "That butters no parsnips" when they think someone is giving them a fast game of talk.

Pea in a Hot Skillet: when natives of these parts wish to describe a person who is extremely active, they say he is "jumping around like a pea in a hot skillet." Some folks who are fond of the picturesque have other words they substitute for "pea" in this expression.

Persnickity: unusually fussy and particular about one's food and easily annoyed by things such as drafts, opposing political opinions, oddities of speech and dress, people who sing while taking a bath, and the smoke from a five-cent cigar. Although a doctoral dissertation has been written on the derivation of this word, its origin remains obscure.

Pindling: small, ill-nourished and not at all thriving. Although usually applied to a child who appears pale and thin, the word is sometimes used to describe a calf or chicken not coming along as it should.

Poor Man's Manure: an early spring snowfall of an inch or two that melts gradually when the sun comes out, giving all its moisture to the top soil. This is thought to be more beneficial to the land than an ordinary rain, which may run off quickly, eroding the field and leaving only part of its moisture for the ground. This notion that a spring snow is a boon to the man who cannot afford extra loads of "dressing" is an example of Yankee optimism.

Puckersnatch: This term the old-timers used to describe a hasty and unskillful job of sewing. The word, invented by some old lady with a penchant for pungent phrase, describes admirably both the appearance of the completed work on the garment and the motions of the person impatiently and hurriedly plying her needle.

Hill of Beans: another one of the "It don't amount to" expressions. Apparently a Yankee feels that a hill of beans is considerably less valuable than a hill of corn or a hill of potatoes, or perhaps he never put in any time considering the matter, and says "It don't amount to a hill of beans" for no better reason than that it rolls off his tongue more easily.

Sea Turn: A breeze off the water anywhere along the Yankee Coast. In summer it means relief from a baking hot spell; in winter a relaxation of a cold wave that has rolled down on us out of the Arctic Circle. We have them in spring and fall, too; foggy days with a salt smell when it is thick outside and one hears the horn on the lighthouse thuttering away at regular intervals, a steamer whistling somewhere out beyond the ledges and it seems mighty good to be ashore.

Sitting Britches: When the old-timers said of anyone, "He has his sitting britches on," they referred more to a state of mind than an actual garment. Such a person was one in the mood to take his ease and stay and stay and stay, instead of getting on about his business. And a corollary is that he talked and talked in a vein not at all entertaining. Mayhap this expression indicates the impatience of the host as much as the over-inclination of the guest to remain too long on his posterior.

Snow Eater: a sea turn in late February or early March coming in from the south or southeast. The warm air from off the ocean reduces the snow cover as does not even the sunniest day, there is a lot of fog, usually a drizzle of rain, mist rises from the drifts, the water runs at the roadsides, and the brooks are bank full. Here and there, as the snow is eaten away, appear patches of moist grass, and for one who looks sharp, the first faint tint of green.

Sortilege: old-time Yankees sought help in time of trouble by laying the Bible flat on the table in the "front room," thrusting in a finger at random and opening "the Good Book" at that point. Every verse on the two open pages was then studied with infinite care to see if in one of them lay the answer to the problem and generally they found that someone in Biblical days had travelled the same rough road and managed to get over it somehow.

Stivver: to get moving. A mother would say to her boy, "Now stivver along to the store and don't be all day about it." Sometimes it was used to describe hard going. An old lady might sigh and say, "Well, I'll manage to stivver along somehow."

To Hell I Pitch It: one of the expressions that marks a Marbleheader, be he walking along Front Street down by the harbor or serving aboard a U. S. cruiser on the Mediterranean station. Lobstermen say it, and so do schoolboys and respectable ladies and men who set out in the morning for their jobs in fancy offices up in Boston. Tell a Marbleheader that it is profane and he, or she, will look at you in amazement and ask you what in hell you mean.

Trout in the Well: a careful householder often caught a trout and dropped him in the well so the fish would keep the water clean by eating insect larvae and green algae. Most people in the country felt that water a trout could live in was bound to be good, pure drinking water. Although some folks, instead of a well, had spring water piped into a cistern made of a half hogshead and setting beside the kitchen sink, yet they kept a trout swimming around in their drinking water as a guarantee of purity.

Vamp It Up: The vamp is the upper part of a shoe, and this expression is used in the shoemaking towns to mean strengthen, patch, or provide with a new part. Not to be confused with the verb "to vamp" common in the Roaring Twenties, frequently applied to seductive behavior by the female of the species. This verb is derived from the fancy that a too-enterprising woman resembles the aggressive vampire bat in pursuit of its victim.

Winter Never Rots in the Sky: When there have been some mild weeks and it appears we may be going to get out of it easy, folks up this way say, "Winter never rots in the sky," which is another way of saying that today the lilac buds may look as if they are swelling, but tomorrow morning you may wake up to find a northeast blizzard howling around the corners of the house, a foot of snow on the level and drifting.

Your Ox Won't Plow: used by the old settlers in reference to an ox without the strength or will to work to make him a useful animal for the heavy work of pulling a plow, it later came to mean anything not performing the function for which it was intended. An old-time judge, after listening to a lawyer make an argument in behalf of his client's case that did not seem at all convincing, disposed of the matter with the simple statement, "Your ox won't plow."

Charles F. Haywood '25, Boston attorneywho compiles old Yankee definitions, haswritten not only "Eastward the Sea" butalso an earlier sea novel, "No Ship MaySail," and a novelette, "You Need a Complete Rest."

Merrill Brook Cabin, primarily for alumni use, was opened in the College Grant last fall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

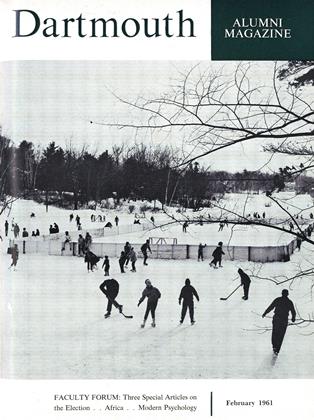

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleProblems of Land Development in the New African Nations

February 1961 By BARRY N. FLOYD, -

Article

ArticleSome Thoughts on the Election

February 1961 By ALAN FIELLIN,

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Millennial Mindset

Mar/Apr 2011 -

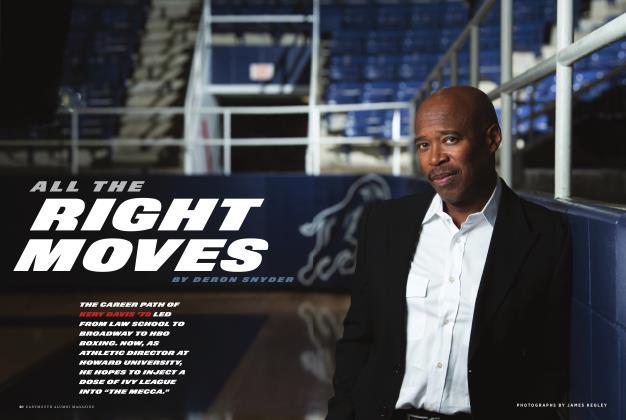

Cover Story

Cover StoryAll the Right Moves

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By DERON SNYDER -

Feature

FeatureAs the Century Turned

JUNE 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Train Robbery

June • 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

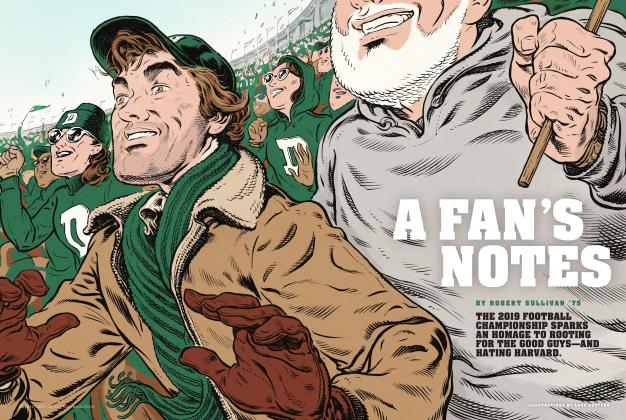

FEATURE

FEATUREA Fan’s Notes

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75