The following account was written by F. Stirling Wilson '16 for the 1916 Balmacaan Athletic Club Newsletter, which he edits for his class. It is printed here in agreement with the '16 men who believe it should have wider Dartmouth readership.

WHO had the idea? So far as I know, it was Madame Rosika Schwimmer, a Hungarian, and if I am any judge, a very sincere and honest lady who had a vision: if only some plan acceptable to all the belligerents, and especially Germany and Britain, could be devised, the war could be ended, lives and property saved. At that time hardly anyone realized the deep cleavage in beliefs between the two. She interested Henry Ford in the idea, and he put together a staff to select a group of prominent people who would cross the Atlantic, meet with other non-belligerents, and draw up a peace plan. Many prominent people were invited; few went along, but there were some. Jane Addams of Hull House wanted to go, but was too ill. One of the largest groups was composed of newspaper men, apparently all of whom prided themselves on being realistic cynics, but whose minds seemed to be made up before they ever sailed that there was no sense in Schwimmer's idea or Ford's efforts to implement it. I derived a poor opinion of newspaper men from that experience that I have never lost.

John Dorland Cremer '16, my roommate, had attended a meeting at Cornell of the International Polity Club and had met Karl Karsten, later a distinguished statistician. Karsten was authorized to select a group of college students to go with the Expedition and exchange ideas on peace with foreign students. Karsten invited the students he had met at Cornell, so Cremer got an invitation. He declined, but wrote a recommendation for me as his substitute (at my request) and armed with that, and a letter from Prof. George Ray Wicker, I took a 6 a.m. train from Hanover (without even consulting Dean Laycock) and went to Ford's headquarters in the Biltmore. By 6 p.m. I hadn't been able to see anyone, but then bumped into Fred Sniffen who was the transportation expert; Fred took me through a back door; I met Miss Rebecca Shelley from the University of Michigan; she took me to Karsten and he told me to go to Washington, get a passport and come back next day. That was Thursday. I was back Saturday with the passport but my name was not in the lists in the papers as selected guests of Ford. Six of us from various colleges were finally pushed up the gangway onto the S.S. Oscar 11 with one steamer ticket amid terrific confusion on the dock. We sailed December 4, 1915 at 4 p.m.

After a very stormy voyage of nine days, during which I thought over the prophecies of my family and friends that the Germans would surely torpedo the ship, we were captured by a British cruiser, which took off many bags of mail, which they said were stuffed with sheet rubber for the German Army. Two days later we got to Christiana (Oslo now) in bitter weather. Henry Ford had been friendly with the 34 college students on board, but was obviously bored by the many people who pestered him with advanced ideas on the "thisness" of "thatness." When he caught a bad cold he retired to his cabin for the rest of the trip, went to a sanitarium in Norway, and was advised by his doctor to return home on the next ship, which he did.

We were banqueted and cordially received in Norway and the mass meeting held with local citizens was a big affair which engendered much enthusiasm. I had a room in a small hotel which was colder than one of Armour's frigorificos, and where they served us several kinds of cold fish, lobster, etc. for breakfast until we demanded something different. The beds were equipped with feather mattresses instead of blankets and when one rolled over, the mattress usually slid off him onto the floor so he was up and down all night in a cold room. However, we met some beautiful coeds, went with them to Holmenkollen, the skiing resort above the clouds, and gradually congealed. I corresponded with one of them for years afterwards.

From Norway we went by train to Stockholm, through deep snow and zero weather. The 12-hour trip took 24 hours, and we slept in seats and on the train floor. Everyone had a cold and a bottle of cough medicine so that the car smelled like a newly oiled highway. We arrived in Stockholm when it was still dark, were conducted at once to comfortable hotels, and my roommate and I went to bed immediately and slept in those comfortable beds till 4 p.m. When we awoke it was dark again. To get our meals we had to go to the Palace Hotel, a grand edifice with a palm garden in the center, but little heat, little light, a cheerless place, but with very elaborate meals. After some insistence we obtained mineral water to drink with the meals. Ford was paying for everything, even our laundry.

We spent a week in Stockholm, holding meetings where there were a lot of speeches, many of which we couldn't understand in either English or Swedish. Our reception was cordial and the press made favorable comments concerning Ford's plan to "Get the boys out of the trenches by Christmas" but it was after Christmas Day before we left, and all of us were homesick. Peace seemed far away. We saw the sights of Stockholm, a beautiful city when not frozen, we saw their fine big department store, rode sleighs, met Swedish students, dodged death in Swedish taxis and ate delicious Swedish pastry.

By New Year's Eve we were in Copenhagen, traveling by train and ferry. We hadn't seen the sunshine for weeks, and Copenhagen was dark and gloomy, but a beautiful city. Here we were prohibited by law from holding a meeting with local pacifists, but we were feasted at the Royal Shooting Club on New Year's Eve, after which a Nebraska student and I accompanied a Brooklyn Eagle reporter to Wivel's, the famous night club, and one of the gayest spots I was ever in. I never drank anything in those days so got a very objective impression of this wonderful place. Another evening we were banqueted, and a singer from the local opera sang "Carmen" for us. Next day I was delegated to present him with a loving cup. I took it to his apartment and was invited in but seeing the family at dinner I declined and have always been sorry, because later I met many Danes and thought they were charming people, and the girls beautiful. Here also we didn't make much impression on the war, but we saw Hamlet's castle, the royal palace, some fine museums, including one in the city hall which was on the square opposite my hotel. There a big bell struck all the hours, and I woke every half hour to pick my feather bed blanket off the floor. I had my picture taken with an American gentleman I met in the hotel and later found out it was Dr. Frederick Cook, who claimed to have discovered the North Pole.

In Copenhagen the American Ambassador, Mr. Egan, gave us a party at the Embassy, and we met Americans who had lived in Copenhagen for years and loved it. The climate there is milder than in Norway or Sweden, but gloomy and gray in winter. Because it was considered that our lives would be endangered by going to Holland by sea, we were allowed to go through Germany in a special train, with armed guards on the platforms and shades drawn. I had taken a stateroom, with my roommate, as soon as we got on the train, but we were tossed out in favor of Mrs. Fels, the soap widow (Fels-Naphtha), who had a priority over any student, so we didn't have a place to sit down on that train except when someone momentarily left his seat and we could grab it for a short time. The ride through Germany at night was uneventful and we came to Oldensaal, Holland, at 4 a.m. where we were given coffee and rolls. Soon we were in The Hague, modern and orderly, and were taken to a fine, luxurious hotel. Later we had time to see the deserted Peace Palace, and we made side trips to Scheveningen, the seaside resort where it was sunny and springlike.

Suddenly it was discovered that there would not be room for the entire party on the S.S. Rotterdam, so the students were sent back on the S.S. Noordam after only three days. En route home we got dispatches that in the big meeting between American, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish and Dutch delegates, a battle had broken out between the pro-German Swedes and the pro-Ally Norwegians and Danes, who had joined our party, and the peace effort came to nothing. The S.S. Noordam was a nine-day ship but we encountered terrible gales, heaved to for 24 hours, rolling and heaving, but getting so used to the motion that we developed great appetites. And the food on board was good, so we didn't care when we got home. We ran out of coal and put into St. John, N. F., to refuel. My roommate coming back was George Wythe, from the University of Texas, later a relief consul in Europe and later with the Department of Commerce, a very fine person. We had a stateroom right over the propeller, and with the bow and stern describing great arcs as they rose and fell it was very much like trying to sleep in a fast moving elevator in a four-story building. Just before we got home the student from Yale borrowed ten dollars of my meager funds, and he hasn't repaid me yet. We got back January 4, having sailed just eight weeks before to the hour (4 p.m.). The students who had been given letters of accreditation from state universities and other colleges were received with open arms. Dean Laycock received me with dark looks and didn't want to re-admit me to college, but finally did. H. S. Person made me leave Tuck School because I had lost so much time, so I took literature and psychology courses, discovered Francis Lane Childs and Curtis Hidden Page and enjoyed my studies more than I ever had before.

...Did anyone suggest anything better to stop the war? If so, it has slipped my mind.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConclave in Cleveland

March 1961 -

Feature

FeatureEducation's "New Frontier"

March 1961 -

Feature

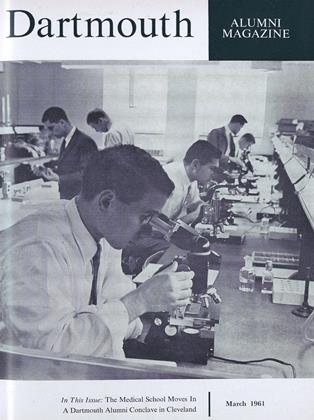

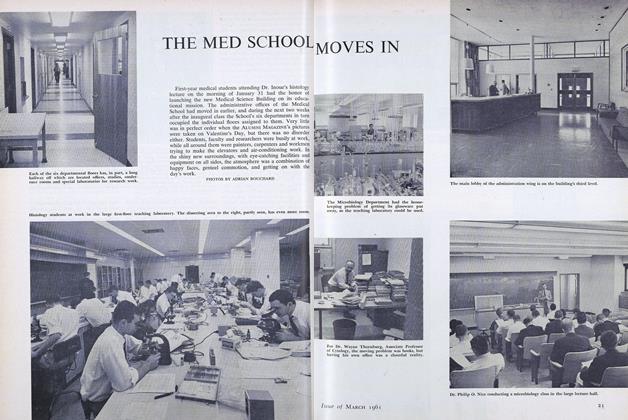

FeatureTHE MED SCHOOL MOVES IN

March 1961 -

Article

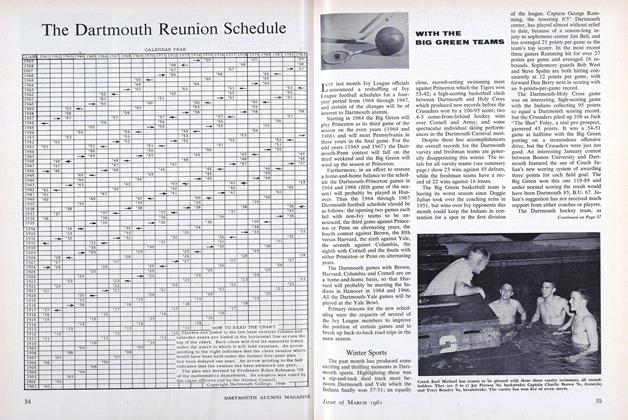

ArticleWinter Sports

March 1961 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

March 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, JAMES L. FLYNN