Brie of the most common indictments of the efficiency of academic institutions has been the fact that a very expensive plant stands idle for three months of the year. The difficulty has been to devise a plan that would permit institutions to break out of the straight-jacket of the nine-month academic year. Although Dartmouth was not the first school to go on year-round operation, I believe that the Dartmouth Plan is the most attractive such option yet adopted by any college.

Using the physical plant for 12 months rather than 9 has advantages only when the student body is increased. Otherwise, expenses increase slightly without any gain in revenues. But if in moving to year-round operation, one accomplishes a significant increase in the student body even though one must add proportionately to the faculty and the administration, the fixed costs of the institution remain unchanged and one achieves an overall lowering of the cost of education per. student. At the time we adopted the Dartmouth Plan, every Dartmouth student was receiving a subsidy of roughly $3,000 because the annual cost of each student's education was that much greater than the tuition charged. We succeeded in achieving a substantial increase in the student body at an average subsidy of about $300 er added student, thus significantly lowering the average cost per student.

We can accommodate 3,200 undergraduate students at Dartmouth using a combination of dormitories, fraternities, and some living quarters in Hanover and surrounding towns. Expanded opportunities for off-campus study, particularly in our language-study-abroad program, add about 200 students per term. Thanks to the Dartmouth Plan, our goal of 4,000 undergraduate students will soon be achieved.

In adopting the plan the faculty voted to bring our graduation requirements more in line with those of other colleges. Reducing the number of terms from 12 to 11, we set a graduation requirement of 33 courses - the most common academic requirement at comparable institutions is 32 courses. In addition each student is required to elect a summer term as part of his or her attendance pattern. If each student spends only 10 terms on campus during fall, winter and spring instead of the traditional 12, it is possible to increase the student body by 20 per cent without increasing the number of students on campus in any given term.

While accommodating a larger student body to implement coeducation may have been the chief goal of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the plan was also recommended for its important educational advantages. The Dartmouth Plan provides a new degree of flexibility for students to design their own academic calendar. In addition to choosing exactly which terms they wish to attend, they have the option of finishing in three years if they are in a hurry (and very few of our students are) or gaining additional time for reflection by spreading their education over five years. But the most important opportunity presented by the Dartmouth Plan is the holding of significant jobs during leave terms. While summer jobs have long been traditional for students, many challenging jobs are not available in the summer. In addition it is now easy for our students to arrange to be on leave for six months at a time, thus making them candidates for more interesting jobs. At a time when so many students have serious doubts about what they wish to do with their lives, the chance to try out a future profession while they are still undergraduates is a very valuable opportunity.

Dartmouth students, with their customary ingenuity, have also used their leave terms for a wide variety of experiences. It is common for students enrolled in foreign study to spend an extra term traveling. One student managed to stretch an overseas job into a round-the-world trip. The Dartmouth Plan has also provided new opportunities for athletes to be members of national or Olympic teams by scheduling their leave terms appropriately. The record so far is held by a student who is a member of a national team both in the summer and in the winter and yet will graduate with his class. At a time when young people clamor for freedom of choice, the flexibility of the Dartmouth Plan is proving highly attractive.

The Dartmouth Plan can also be a boon, for faculty research. Since faculty members have considerable choice as to which three out of four terms they will teach, it is easy to combine a one-term sabbatical with summer teaching and spend half a year at another institution. Even without a sabbatical, many faculty members have opted to teach four terms one year and two the next year to provide a six-month break that can be invaluable for completing a scholarly project.

A not insignificant by-product of the Dartmouth Plan is the fact that we have been expanding our faculty in a most favorable job market. As I have noted previously, this should have a major impact on the quality of the faculty.

After two-and-a-half years' experience we may safely conclude that the plan works and that it has proved enormously attractive to applicants to the College. That does not mean that the plan is perfect; as with any radically new idea, there is room for improvement.

One problem is the distribution of courses among four terms. While the summer term is equal in academic quality to the others, it is also quite different: there are no freshmen present in the summer, and most of the students are juniors and seniors. This provides a unique opportunity for departments since the summer is the one term when they can be sure of having all their majors attend at least once. Some departmental offerings have not taken this fact sufficiently into account. And since students ave to plan their Dartmouth Plan at least two years in advance, major inconveniences have been caused by departments changing their course schedules at the last minute. These are transitional problems that we are working hard to overcome and that will surely be ironed out.

In admitting Dartmouth Plan classes we have carefully stipulated that students would not necessarily be given their first choice of academic pattern. I find it strange that some students resent this fact, when in the past they had no choice about the academic calendar! We have not yet figured out a way of making the spring term with baseball and mud season as attractive as the fall term with football and the beauty of a Hanover October. One of the encouraging signs that these problems will be solved is the fact that some students who attended a summer term only because they had to are now coming back voluntarily - indeed, enthusiastically - for a second or even a third summer in Hanover. Although social activities have been much less intense in the summer, a combination of high academic quality, a relaxed atmosphere, and the opportunity for outdoor activities has proved very attractive. One would think that in the long run summer will be one of the most popular terms, but it is hard to break the conditioning of grade school and high school that tells you that summer is a time for vacation.

While all classes have a common freshman year experience, no similar provision was made for a coming together in the senior year. A consensus is growing that there has been an erosion of the senior experience and that something must be done to correct this problem. While advanced-placement programs and the oppor- tunity for acceleration enabled a number of students to graduate in less than four years even before the Dartmouth Plan, the 11- term requirement has made early graduation much easier. The dilemma is how one can make the senior year a more meaningful common academic experience without losing the freedom and flexibility of the Dartmouth Plan. A number of interesting proposals are now under consideration.

One concern in adopting a plan in which students have so much freedom of choice was whether we could correctly estimate the number of students who would be on campus in a given term. It was ironic that those officers in charge of guessing achieved nearmiracles of accuracy, and yet there has been overcrowding in the fall term through no fault of the Dartmouth Plan. When I first took office, students had to receive the dean's permission to live off campus, and there was a long waiting list for this privilege. Getting out of the supposed regimentation of dormitories was "the thing to do." The combination of a change in student attitudes and a steady increase in the cost of off-campus living has driven students back to campuses all over the nation. At Dartmouth last year 100 more students wanted to live on campus than the year before. We worked out a temporary solution by using the Hanover Inn Motor Lodge as a dormitory for the fall and winter terms. The Trustees are now considering whether to build additional dormitory facilities.

Perhaps the most vexing problem under the Dartmouth Plan has been the assignment of rooms as students move off and back on to the campus. We now share a problem with hotels and airlines who know that a certain number of reservations will be canceled, or that there will be "no shows," and therefore that they have to "overbook." Here we have run into a long-standing Dartmouth tradition that allows students to sign up for rooms several months in advance. Since this used to occur mostly in the spring term, when upperclassmen could take advantage of rooms to be vacated by graduating seniors, the traditional system used to work very well. The freshmen, of course, had to take the left-over rooms, but they didn't know enough to complain about the system! For this year's fall and winter terms we knew that of some 3,250 students who told us they would "definitely" be here, at least 50 would not show up, due to illness, academic difficulties, or other reasons. But we had no way of knowing which 50 students, and had no choice but to put a small number of students on waiting lists until the opening of the new term. The problem was further aggravated by rumors that a large number of students would, end up without rooms (none of them did). One of our major challenges is to design a new method of signing up for rooms that is equitable to all students and eliminates this unnecessary concern.

As with any radically new plan, there is a natural human tendency to make it a scapegoat for whatever one may not like at Dartmouth. I have been amused to hear students blame the Dartmouth Plan for problems that students complained about with the same vehemence 10 or 20 years ago!

It is my judgment that the great freedom and flexibility that students have gained, and their opportunity for significant offcampus experiences, far outweigh the few problems that were caused by the Dartmouth Plan. I am also convinced that the remaining problems can be solved as we gain more experience and find better ways of administering the plan. During the last two years, we have received many inquiries from other institutions as to how our plan works. Given the financial plight of higher education and the necessity to operate institutions more efficiently, I would not be surprised if the Dartmouth Plan - today a radical experiment - were someday to become the pattern for higher education in the United States.

Features

-

Feature

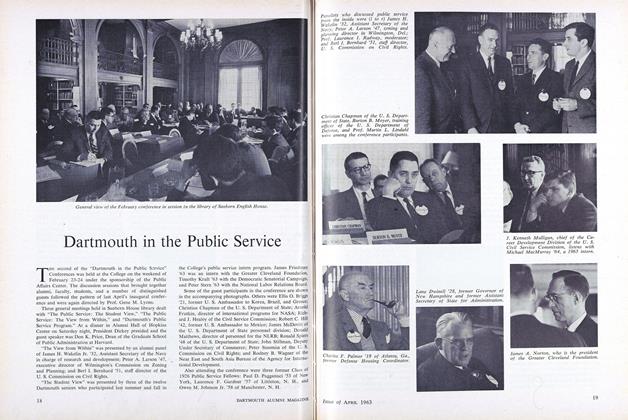

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

APRIL 1963 -

Feature

FeatureHonorable President in Japan

MARCH 1965 -

Cover Story

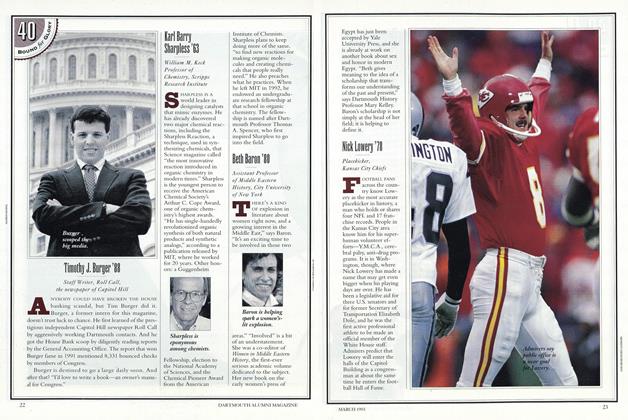

Cover StoryNick Lowery '78

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureThe Last of the Liberals?

May 1981 By Frank B. Wilderson -

Features

FeaturesWell Read

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER -

FEATURE

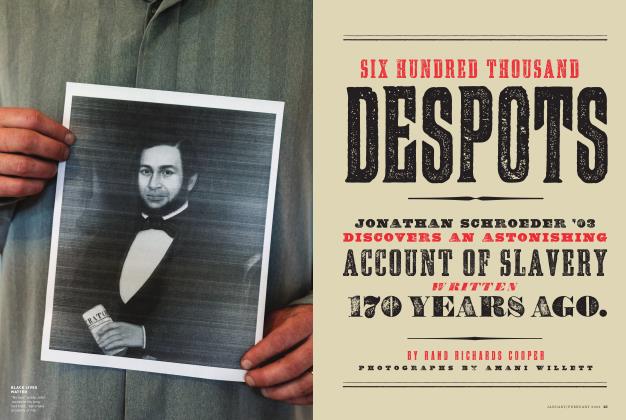

FEATURESix Hundred Thousands Despots

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By RAND RICHARDS COOPER