David Riesman's article in the April Atlantic, dealing with the present collegegeneration, was the starting point for theseniors' discussion. Riesman claims thatcollege students have a low opinion ofwork, particularly in large organizations,as a source of personal realization andconsequently look to early marriage, afamily and a nest in the suburbs as meaningful things and to the job as primarily away of making a living.

I find it difficult to accept Riesman's statements about bureaucracy. I feel that four years here have provided me with the means of working within the framework of this so-called bureaucracy, or if I don't accept it, at least of finding other ways to assert my individuality. At the same time, early marriage seems like the action of an individual who realizes that he can't adopt the rebel role in society, and so in order to assert himself, he finds this the easiest kind of commitment.

Rather than being an easy outlet, wouldn't this in many ways put him in a tougher spot? Graduate school would take care of him for two years, but the guy who gets married right after college is stepping out on his own quicker and is expressing his individuality. You're generalizing something right at the start, saying that people who do get married are afraid of stepping out on their own. I don't think this is so — I'm getting married soon, and that's one reason why I don't think it's so.

You're talking about two kinds of security here. I doubt that anyone here, in an Ivy League college, doesn't know where his bread and butter are coming from. But this other kind of security that might be called identity security or emotional-stability security is the kind Tom means when he talks about early marriage. And this is the kind we seem to be retreating into.

Let me second guess you and try to figure Out what you mean by this rebel role. Do you mean responsibility to yourself?

Yes, I'd accept that.

We're talking about two kinds of escape. One is to security that comes with marriage and prescribed responsibilities, and the other is going on to graduate school. And I think there are a great number of people in college who want this second kind — the escape away from prescribed responsibility, whether it's just a responsibility to yourself or one that's not static or prescribed. This is seen from the perspective of just one isolated Ivy League college. As Riesman viewed the total university world, I think he's a lot closer to the truth.

Then you think Dartmouth is that different?

Yes, I would say that the Ivy League schools tend to breed more of this second kind of escapism; in other words, the graduate schools prolonging the present state of affairs.

Today there is tremendous pressure from without. The international situation lends instability to existence, particularly now when the college graduate is ready to step out. Well, he's got to find something to hold on to, and marriage and graduate school are just two examples of the way people are grasping for something meaningful. I have the feeling that college students today are really trying to reevaluate their whole concept of what life is, what man's values should be. This is the broader question, rather than the mere steps one is taking to gain security.

r We ought to stop talking like a bunch of sociologists and talk from the per" sonal point of view. Speaking for myself, I think my job is one way in which I can establish an identity that is going to be meaningful. I think Riesman is dead wrong. I don't intend to center my individuality and my personality in the family and community as completely as he seems to think.

Who doesn't want to be an individual? I'd love to be a writer and strike out on my own5 without all this materialistic point of view. But the world is a rough place for a writer or an artist just out of college. There's an awful lot of pressure on you to sacrifice your individuality.

Maybe the odds are 100 to 1 that we will have to compromise, but this doesn't mean that we're any the worse off for having thought this way. I think we will go into whatever we are going to do eventually with the realization of what it means to us and what we as an individual will put into it. I deplore the situation where a man doesn't think this and just looks on G.E. as a sort of barbiturate.

You fellows seem to set a great value on individuality. Swinging this whole business closer to the College, would you say. that four years here at Dartmouth have contributed to your individuality or to the way you feel about it?

To me they've contributed tremendously, but in a negative way, because you have to fight to maintain your individuality. To some professors and administrative people you must assert it in order to get somewhere.

Mainly because you've had to fight for it?

Yes, I've had to fight for it.

I think that along with it goes this trend that was outlined earlier. You come up here fresh from a fairly secure situation, steeped in family and home tradition, and then you find all of a sudden that the values you've held for years don't hold up under the pressure of Dartmouth's academic probing. But then as you progress through four years you get to the point where if you follow this out it leaves you with nothing. At this point what you do hold to be true is your own, because you have to reestablish your beliefs, and they are yours, not something ingrained in you and that you've accepted without question. This is certainly a part of this individuality that you get here.

I think Dartmouth gives you, as Dave said, a sort of negative stimulus to being an individual. You have this mass of faces around and you have pernicious journals like the Ivy Magazine telling you how to dress and how to drive your TR-3 down to Lauderdale, and if you have any potential in you or any longing to hold your own beliefs or staying away from mass movements, it sort of pushes you to do this.

I can see where you can develop a positive concept out of a negative one, but I'm just wondering where the positive comes in. How can a college be more positive than its tempo?

You're pointing to a prime defect here at Dartmouth, and probably at most colleges and universities. It seems to me that the other way you can provide a positive stimulus to strengthen the student's individuality is through human relationships. This can be sought on two levels. One is student-student relationships and I think a very small percentage of students are able to find this kind of stimulus among their fellow students. Second and more important, and where I think Dartmouth is lacking most, is student-faculty relationships. Because it seems to me that the humanity is almost completely lacking in the rapport, the stimulating intellectual rapport, between 90% of the students and even one faculty member. You might question this, but I think that we who are sitting around these microphones are exactly the sort of guys who might have sought this relationship with faculty members. It's almost ludicrous to talk of a humanities division because humanity implies above all else this very close interpersonal relationship. Most of the humanities, it seems to me, are taught with almost empirical coldness.

Many of our outgoing, more or less avant-garde faculty men — you almost have to be avant-garde these days in order to be a humanist — seem dissatisfied here. Now whether this is Dartmouth or whether they'd be dissatisfied in any academic community, I don't know, but a lot of these men up and leave. There's a kind of leveling influence that crops up again and again, the faculty included. Institutions such as fraternities, good as they are, tend to level one's individuality. One thing about Dartmouth is that there is more social pressure in a school of this size than in any place I can possibly imagine. You can't lose yourself here as you can at Harvard; if you don't make it with other men you just don't make it at all.

I came here with wonder-wide eyes thinking I was going to find a vibrant intellectual community, but I found that people didn't carry any sort of intellectual endeavor beyond the classroom. It seems to me that the students themselves don't generate the sort of exciting atmosphere you'd expect at a college of this standing — and you begin to wonder, if Dartmouth doesn't have this, what does the University of Minnesota have? Or maybe the University of Minnesota is better, I don't know. And I think student-faculty relationships have a lot to do with this. A good faculty is here if it's tapped, but I don't think many people are interested in tapping it. They are interested in going over to the house and downing a few beers.

I don't quite agree with this. It seems to me, getting back to this negative stimulus bit, that if you accept the idea that there is this constant leveling process, it's your decision whether you are going to accept it or whether you are going to fight against it or work within it to assert yourself or commit yourself. I found a tremendous value just by being fairly aggressive about it with certain friends of mine. Some of our discussions have been terrific. It depends on the individual whether he wants to seek it out. There's a benign sort of acceptance of this leveling idea; we look around us, we generalize, and then retreat.

Well, I can tell you from four years on the Jacko — just look at its quality in recent years — that it's virtually impossible to get men to produce good art or good lit, and I can't believe that a campus with this high an overall intelligence doesn't have it. The exceptions who do try to produce are looked at, pointed at, you know. You rebel against this sort of thing and it alienates you.

I'm really surprised to hear the rest of you talk this way, because I thought I was unique in experiencing this alienation.

I think we're all surprised.

This school is tending more and more towards mathematics and science, and is really getting away from the arts. I think there's really a definite lack of ability here to perceiv.e what anything artistic is.

I don't know whether I agree with you or not. Going back to your criticism of the Nugget crowd, I think a lot of students recognize a really good movie as a work of art, but they're almost afraid to sit there quietly and enjoy it.

It would be fine if they were afraid inconspicuously and quietly — I feel more strongly about this than you do - but I think there is an ardent opposition to people who, as inconspicuously as they try to, respond to things. Maybe I'm way off on this, but there's a sort of opposition to Intellectuals with a capital I.

I don't take as a dim view of it as you do. I agree, there is a sort of anti-intellectual feeling, but I think this is only when students get in groups. Individuals and little groups of two or three when they get together have tremendous discussions. I don't think that individually there is any looking down on the intellectual.

This last vacation I had a chance to visit the University of California and I could feel the tremendous vibrancy of the place and the interest in all sorts of things. Perhaps the fact that it is coed has something to do with it. If Dartmouth were to go coed, this might change this leveling environment we seem to think is here.

Before we get off on this question of whether Dartmouth should go coed, I would like to suggest, once we recognize this leveling influence or disinterest in intellectualism, that this is possibly due to the fact that the Dartmouth man has an image that he feels obligated to live up to. That's my feeling and I've puzzled over it.

Some 700 freshmen came in as we did — perhaps not all but the great majority of them — looking and hoping for a sort of feeling of electricity zipping around in the air between professors and students and with students — and then all of a sudden that died out. Now why did it die out? I'm interested in finding out. I think that a lot of it deals with the faculty. It's a tremendously important area. Riesman mentioned this, that students in general feel that they have no control over the curriculum. They feel they can't get close to the . faculty. Except for specific men or various small departments, the majority of the- faculty members here really aren't willing to give you the time of day - they're not willing to sit down and talk with you about something. This is an area which Dartmouth as a whole must go over. Some people say, "Well, this is just the older men who've been here thirty years or more." But that's wrong. In my experience, it's more often the younger men, the ones who are here for two or three years to get a prestige name on their records and then go off.

I don't think this is true. I can recall a number of times when professors have gone out of their way to give you much more than the time of day, to encourage you to branch out and to see them whenever you want to. It's up to the student. I think it's more the students than the professors. It's the whole idea of image that Pete's talking about that's the real thing that's stopping us.

Part of the trouble is( that Hanover and Dartmouth are one community and that it's very hard for a faculty member to withdraw and lead his own life apart from the students, which he'd like to do at certain times. And because it's difficult, he's constantly striving to do it and is inclined to repulse any efforts towards greater student-faculty relationships.

I think there is a difference too in the diversity of backgrounds in a place like a university where you have people from all different countries — and graduate students too — wearing clothes that are strange to our eyes. And Dartmouth is pretty inbred; a lot of people both in the faculty and the administration went to Dartmouth and then returned here.

And I think a lot of these men are the very ones who are willing to give their time to the students. I notice that some of the whizbangs in these departments, the men who are going to be great and who have their Ph.D.'s within a few years, are so much on the go that they look on the student as a high school type who couldn't possibly come up with any intellectual feeling. When you get up higher in certain departments you probably can find this intellectual stimulation, yet in some of the big departments its hard to find.

I think a lot of the younger faculty members who come here have been trained in a research-conscious environment, and they're interested in the student who wants to go into their discipline-You'll find that if a student shows promise, the professor will give him a lot of time, but to find that professor whos interested in you as a human being and will sit down and talk with you beyond the subject is almost impossible. I'm talking about a real, full human relationship and not a purely academic, intellectual relationship. Because only within a full human relationship can any kind of real stimulus grow.

But can you demand this of a professor?

I think it's ideal, but whether we can demand it today with all the pressures that are operative, I don't know. It may be unrealistic.

I've been thinking about something. I've come to the conclusion that if you were to choose the optimum size for a college to function inefficiently, you'd pick Dartmouth's size. It's too small to be a great university where you walk in and accept the fact that the teachers are going to be primarily interested in their discipline, where you go to lectures and try to get what you can out of them, but where you have graduate students and teaching assistants all around, people who are intensely interested, and where you also have this cosmopolitan atmosphere. It's too small for that. But it's too big to be an Oberlin or a Swarthmore, where everything is really small and people are accessible. It's just too large to be one of these small, intimate, chatty places.

I think — here's the old scapegoat coming out again — that the administration has done some things to make Dartmouth a more intellectually satisfying place, but I don't think it's done half enough. One way in which it hasn't done enough is in its policy concerning such things as student magazines, The Players, virtually any type of intellectually satisfying extracurricular activity. How much financial support does the College give them?

The fact that for four years Ray and Pete and Ed and Mike, and others here, have worked and done something that was not run-of-the-mill is in itself a contradiction to what's been said.

Yeah, but go into any fraternity basement and pull out nine guys and see what they say, see if they've even realized there's any alienation.

Now here's a thought. We have something here that to my knowledge is unique. How many colleges do you know of that have the fraternities put on fraternity plays? This is something creative, something out of the ordinary. Some of the plays are very good, and whether they're good or bad, there are lots of people who are willing to put in long hours to produce a play.

How many willingly? It's hard to get the guys going.

All right, sure it's hard, but you're going to find that in business, medicine or anything. It's always going to be hard to get people going. Yet some of these plays are pretty darn good. This is something that Dartmouth is doing, and it hasn't come from the administration. Isn't it even better when it comes from the students themselves?

It's like someone yelling from the middle of a sand dune.

I've heard this criticism of the Dartmouth student a lot — that he's uninterested and uninteresting, that he is not stimulated and not stimulating, but when it comes down to pointing to specific people I'd have a hard time making a long list of those who don't contribute and participate and aren't stimulated by something or other. Maybe every man here isn't a beard-wearing artist, but it seems to me that just about every man has some particular interest where he's contributing, and not divorced from the intellectual.

The other idea is helped along by the alumni — you know, the stories about, gee, what wild parties we had. From them you get the idea that 90% of Dartmouth is just parties, but that's not true up here now. Perhaps when we came here we had the wrong idea.

Well, we're spending an awful lot of time working and studying, but people seem to go into class, perform very efficiently and impressively, and then they walk out and are suddenly divorced from it all. And I wonder if this isn't the characteristic of American students in general. In the case of schools like Dartmouth education is just as much a social necessity as it is an intellectual necessity. There are a lot of guys here for whom going to college was just a matter of course, not a matter of decision.

In Europe being a student is something of a distinction, something to be achieved and cherished. I'm not saying that frivolity is lacking in European students, but somehow the American college student seems to be in college because it's the thing to do. You go to your classes and you try to maintain a decent average, but you walk out of your classes and begin to perform socially, in Ray's derogatory sense.

That's one of the things I meant about the lack of diversity in background. I don't think freshmen do come here looking for a great intellectual stimulus. I don't think I did. I didn't know what I was looking for. They don't know what the goal is really until they're here, and then they have this leveling influence that seems to exist. It's mainly because they're all more or less from the same background, and nobody really knows what he's doing.

What about the Med School? It's supposed to be a tremendous place. They have great professors and teachers there, and most of the doctors from Mary Hitchcock are supposed to be great. The students are treated like colleagues, in a way, and why isn't this carried over into the professors of the undergraduate college?

Well, there are two things there. The students in the Medical School are men who have already made the commitment - they are going to be doctors — they are in effect graduate students. Second is the fact that the tools of a teaching doctor are all there. Now the average history professor has to teach freshmen who are going to be doctors, say, and couldn't care less about history, as well as the genuinely interested student who wants to become a history professor. There's no community of interest.

What are we looking for in a liberal arts college — a man who only wants to teach those who are going to major in his subject or a man who wants to teach his subject so all his students will get a great deal out of it?

Shouldn't the administration make a greater effort — and I think they should — to get real "teachers here rather than men who are mainly interested in research? They say it's almost mandatory for a man to produce, to turn out books or something. If he has to do this while he's trying to teach students, and they suffer, what's the purpose of the College?

I don't think it's true that everybody up here, or at least the majority of the faculty, are working to produce and are narrowing themselves into research instead of teaching. I think Dartmouth as an undergraduate college does realize that the major function of a professor is to teach.

I was talking with a professor recently and he said that things were changing so fast in all fields, especially in the sciences and social sciences but even in the humanities, that a professor has to do research to stay on top of his subject and keep it alive and vital for his students. It sounded pretty good at first, but the more I thought about it the more the fallacy of this line of argument struck me. In the first place, research is necessary for recognition and promotion in the academic field, and he's likely to select a piece of work that will please the scholarly elite who are going to read it and not necessarily one that will broaden him and give him new insights to pass on to his students.

It's a question of attitude, not the time spent on research. I think back on two of the best teachers I had here, and they were also two of the most productive men in the College. The reason was the way they looked at the student.

It's sort of a crime that you didn't name at least a dozen right off.

I wonder if there's anything unique in that. I can tell you of one state teachers college where any one Dartmouth professor would be worth the whole faculty put together, but I wonder how we really compare with a place like Harvard or California or some particularly vibrant campus.

I don't think you can criticize Dartmouth on the intellectual product it's producing. Maybe you can in terms of the general concerns men have outside, but when you put the Dartmouth man in academic competition alongside of others, he stands up damn well.

I agree, and when you judge the Dartmouth man on public-spiritedness, public-mindedness, and this sort of thing, I think you must admit that Dartmouth equips its graduates very well with attitudes and a kind of learning that serves in this area.

Well, I still wouldn't say that there's much carryover from the classroom into everyday life. And where does the fault lie — with the students or the faculty? Or with the administration?

y I still think that underlying the student's outer shell there's a real intellectual concern and interest. Maybe his cover attitude is something that's built into the freshman from his first riot during Orientation Week. I don't think very many guys have the guts to assert themselves or establish themselves in the minds of others as being intellectually concerned. This is the big problem.

Well, I don't want this place to go to the extreme of pseudo-intellectualism where people make it a point to establish in everyone's mind that they're intellectuals. But we've certainly got to reevaluate and adjust our whole program here, attempting if possible to change the general attitude.

Atmosphere is a very vague term, but I think that's what we've been talking around for most of the evening — that there's a sort of atmosphere here that makes it almost mandatory to assume a certain pose. And beyond that there are certain tendencies on the part of the administration. In just one area, take the business of off-campus rooming, which is being gradually closed down. Now this was an outlet for a lot of guys who wanted to break out of the dormitory pattern of living, which is the really seething hotbed of mask-wearing. But gradually they're closing down and narrowing in — and the paternalism is becoming suffocating when you tell guys that they can't live off Campus.

I lived off campus last year with three roommates. It was a good existence and I liked it very much. Then I made a disastrous mistake — I moved into the fraternity house. I like all my brothers and it's great as far as social functions go, but the place is about as intellectually alive as a well-regulated crypt. It's magnificent that way.

Up to now we've said the same things over and over again. The question is, what can we do about it?

One positive suggestion is Activities Night. I think that's one good thing to include in the orientation program.

A much more positive suggestion is women — going coed.

You said, Pete, that we'd eventually get into this, and I think eventually has come.

r Well, I'll start it off. I think Dartmouth should be coed.

Second.

I agree. I've thought about this a lot-At first I said, "I don't want Dartmouth to go coed. It will change and never be Dartmouth again." And yet, when you think about it, this is pretty irrational reasoning with nothing to back it up. We've shown, I think, that a change in this direction is necessary.

r The only thing I can see against it 1S that restrictions on such things as hours and having women in rooms would probably be tighter, and they're tight enough now.

Is there anybody here who'd be against having Dartmouth go coed or at least have a sister school?

I think I would. Maybe I'm conservative, but I don't believe there is much to be gained by it. Certainly you would improve social conditions — less social constraints, no more of these big weekends that are forced anyway — but there can be a certain vitality at a non-coeducational institution that I think is here. There might be a little more intellectual politeness exercised if girls were around, and I don't think this would be good. It would throw more students into a middleaged kind of thinking. In a bachelor existence you are allowed a certain amount of irresponsibility — you can be an "intellectual slob" for a while if you want to. There would be less flexibility, and we'd constantly be trying to relate to the coeds as females rather than fellow students. I think we'd be giving up too much.

This idea of treating them as females is a point against you. I think we'd treat them more as minds, whereas now when they come up we treat them more as bodies.

All that having women here would tend to do is to make this a real society.

That's exactly the point I was making. Maybe it's good that this isn't the real society. I object to unrealism, but one of the important things Dartmouth can provide is an opportunity to experience the sort of isolation that has a cleansing effect.

People are talking about preeminence and also about keeping this a small school crying in the wilderness. You can't have both. If they want preeminence they ought to bring women in — and also expand the departments and have graduate students here too, if at all possible.

Dartmouth alumni would rise up in arms with the cry that the Dartmouth spirit would be lost. I'm inclined to feel that the Dartmouth spirit as they knew it is about gone anyway and would be revived some if there were girls on the campus, or a sister school were around. Back in 1925 — my father's class — I'm sure there was a real Dartmouth fellowship spirit, but it's not here now, and it can't be here now.

It's a fallacy to say that because the fellowship doesn't now exist, it's a trend we ought to give way to. It's societal more than anything else. The College is a lot different now than it was in the '20s when fellowship was important. But I think we're going to be thrown into real society, if you want to call it that, just as soon as we're out of this place, and one of the things I've valued here is the chance to remove myself. If it involves a certain amount of unreality, the unreality has been stimulating because it has given me a sort of foil against which to check everything I've ever thought. Having women here would provide us with just what we're going to get when we leave here. Why not postpone this, why not wait?

I don't think we have any choice. Conditions outside Hanover make it necessary that if Dartmouth is to be an educational institution, it move in the direction of reality. Dartmouth cannot exist in Hanover and let the rest of the world go along, because the world will go on and Dartmouth will be left in Hanover.

There's one technological advance that has caused the decline of the Dartmouth fellowship — the automobile. And while the Dartmouth man in the 1920's might have been contented with what he had here, since he didn't have much opportunity to do anything else, we are faced with present-day circumstances and with realities, and it's up to Dartmouth to adapt to them.

Women are a fact in society, you know. Why aren't they here? It's a terribly unreal environment, and breaking out of it is going to be a tough job for a lot of people, myself included. I don't know how many other places there are in this country where you can find 3000 normally functioning males who voluntarily confine themselves to a hilltop.

We develop such a perverse view of women and of recreation. A weekend comes up and you immediately sanctify it and say, "By God, I'm going to have a good time — capital G, capital T." It's a feverish pursuit of joy.

You've mentioned cars and the weekend problem, and somebody a while back said something about the extracurricular organizations having their troubles. Is it true, as some people claim, that there is a relationship between this campus situation and the new educational program, the three-three system?

No, I don't think there is any correlation at all. This all started right after the war. In fact, in many ways it is better now because we have so many new and different activities.

The three-term system could almost help it out. Maybe I'm in the minority here, but I find myself much more able to budget my time with the three-three plan.

One fairly large causal factor, I think, is the pressure on the high school student to get into college and the pressure, once he's here, to make good. As a result, he doesn't get into extracurriculars as early, and once he does find, that he has the time for them, he might feel it's too late to start or that there's no future there and perhaps he's better off just to stick to the books and not take chances.

This is a big, broad, general statement, but with regard to the alumni concern about the state of extracurricular activities at Dartmouth, I think that so often a person who was here 25 or 30 years ago can only judge things from 25 or 30 years ago. As Bill said, the car adds new things. Men coming into college now work one heck of a lot harder than they did years ago, and the alumni are still looking at things from "way back when."

Before we leave this and lest you think we all agree, there is one correlation and it is just plain fear — the fear that students have inculcated in them by parents, and then when they get here and hear someone say, "Look to your left, look to your right; three years from now one of you will not be here."

Yes, there is some correlation in that sense, but I would say that this did not come just with the three-three system. Colleges everywhere are forced to step up their processes, and Dartmouth in keeping has stepped up hers. Men today are required to spend more time, and more concentrated time, in strict academic work. When they do have free time — and there is free time — it's used as an escape from concentrated work and is not channeled into another kind of work.

We've spent a lot of time talking about the College, naturally enough, but before we break up let's get on to something more general. Several times in Great Issues the hydrogen bomb has been brought up — you know, ten years from now we'll all be wiped off the earth, or radioactivity will be all around. Do you guys fear this sort of thing hanging over us?

I'm not sure that you can say that people really fear the atom bomb. I think the whole idea of insecurity everywhere in the world causes people to think of it mainly in terms of their own inner security. College seniors are vitally concerned with forming for themselves a system of values, of faith if you will, something that will have meaning to them as a person. They need some form of security but their vital concern is with gaining it for themselves from within.

There's another answer to it too, a psychological one. We tend to repress the whole area, push it to one side, perhaps because we really are afraid subconsciously, or perhaps we feel that it doesn't concern us that much. I think this is the general attitude — we're afraid to face it really.

It's almost too big a thing to be concerned about. It's just like the conception of hell — is it there or not?

r I feel that people use this fear of the hydrogen bomb as an excuse to refrain from participating, from applying themselves in any kind of activity. They just don't do anything because of the futility that might result if the bomb did land - their efforts would be wasted and so on.

I disagree most emphatically with what Max Lerner said in G. I., that this generation has no sense of tragedy. You do put it out of mind that there is a bomb hanging up there and that someone is going to push a button and here it is, but the essence of the tragic concept is something that enables you to go on in spite of impending annihilation. And annihilation is certain at some time, aeons hence or maybe five years from now. I wouldn't say this is something you can just shrug off. I even have moments when I think of going to the Canadian wilderness and trapping wild game.

I'm not sloughing off the eventuality of annihilation. What I'm saying is that it seems to have resulted in a default of responsibility for one's actions with a lot of people. That's the thing I object to. This fear of annihilation has been with us for aeons; it's just adopted a new form, and whether or not it's present, you just have to adopt a faith that man has not yet been able to destroy himself and that it seems hardly conceivable that he could now, totally. The eventuality of its happening, while possible, is not entirely within reason.

There was an article in the Nation about the terms that have come up such as "megadeath," and the guy called this whole language Desperanto, a magnificent term. We are throwing these terms around. I came out of that lecture by Sprague and thought about it for a while — megadeath? - it didn't mean anything to me but finally it hit me just what a million dead means. But you bring it back to the term - you just say megadeath and stop there. If you really began to grasp the futility of being 21 or 22 and having this hanging over your head, you would literally go to Canada and not just think about it.

Max Lerner said something else, that people about our age cannot conceive that they will ever die, and I think this is probably true. It colors our thinking about the hydrogen bomb. "Sure, it's hanging over our heads and we know it's there, but we can't do anything about it, so what's the sense of worrying and letting it occupy all our thoughts?" This is a kind of repression, but not repression because we don't want to think about it but repression because we really can't conceive of its happening.

I am convinced, absolutely convinced, that the bomb is going to drop, but I do a beautiful job of repressing. It's man's great gift that he represses like mad — you repress a lot of ugly things and this is the ugliest of all. But I go on making my plans to go to graduate school and do certain other things. How do you live with something like this?

Part of it is fatalism. I often feel that it's out of my control, and that whatever happens, happens.

The tragedy would be if we all adopted a fatalistic attitude towards this thing and failed to recognize the responsibility we have towards preserving ourselves. I think one of the best things we can do is to adopt an optimistic attitude towards this thing — to say that while it's possible that the bomb will drop and we'll all be wiped out, I can't conceive of man doing this to himself. I just can't conceive of it. I don't think this is repression as much as it's the feeling that man isn't that stupid. He can't be, he wouldn't dare be.

Look at the Eichmann trial. If the execution of six million Jews was possible, then I maintain that it is possible for one of the powers with nuclear weapons just to destroy things.

Well, my feeling is to' work within this framework of possible annihilation with the utmost optimism, not letting it become fatalism. Otherwise you're throwing everything out of your own hands instead of bearing some responsibility about it.

I'm not defending fatalism, but to harp on Reisman again, this is one of his points — that the very bigness of what we are getting into prevents us from thinking that we can have any effect on it. And that's a form of fatalism.

I think America has a tremendous tragic sense, and it comes from a basic feeling of inadequacy to deal with anything in a meaningful way.

This is the sort of sentiment that's not only fatalistic but could be fatal. We just have to take it into rational realization and also into our emotional consciousness that this is something that has to be grappled with. After all, it's people from our generation who are going to be dealing with problems of disarmament and so forth. We can't dissociate ourselves from impending doom.

I think that the greatest positive thing that can come out of this if we survive it, if we can remedy it, is a heightened consciousness and realization of the deep meaningfulness of life. The primary prerequisite for dealing with the problem is the feeling that life is worth while, is worth going at and trying to do something about. If we don't have this . . .

I've heard criticisms of the young college conservatives who seem to be growing in numbers on some campuses — that certainly it's easy for students our age to be conservative because they've never known the misery or tragedy that brought man to be liberal. In other words, this generation hasn't really known depression or poverty, and even though they have known war, they haven't known it personally. There is really nothing tangible in the present-day American affluent situation that lends itself to developing this heightened sense of awareness that will then be reflected in a personal feeling.

Yes, this is rather pessimistic — it's hard to separate the individual attitude from national policy or from politics and the ramifications in international affairs. But I wouldn't entirely go along with that statement about the trend. I think right here in this discussion has been manifested a lot greater concern than most members of the more adult generation give us credit for.

Along with the concern, one important consequence of the bomb is a tremendous sense of disengagement, of being cut off from any sort of influence on your fate. I feel so apart from the whole operation, the whole outcome of the power struggle. In the beginning I started joining organizations left and right — organizations devoted to stopping the arms race and so on. Then I began to feel, "What good am I going to do?" It all seems so damned ineffectual, and now I feel completely cut off from what is going to happen. I don't even feel myself watching it, because there's nothing to watch. You read the newspapers, but who makes the decisions?

Well, I feel rather powerless too, but rationally you know that you are part of the race of man and that sometime you are going to have a voice, however small or ineffectual or crying in the wilderness. Some voices are going to have effect, and let's hope it can be the voices that think life is meaningful. Therefore, this heightened consciousness of what existence means is the starting point.

That is because of our position here at Dartmouth. Here we are just sort of reflecting without enduring too much reality. I have this feeling that I am going to have to do something or I am going to explode, because this complete state of reflection that I'm in is going to drive me beyond myself. So if I could get out of here and get into something that's bigger than myself, that has a purpose to; which I can devote myself, then I'll lose part of this detachment and will feel more purpose in life.

Mike is right. Many of us feel this way — right now we're powerless and there's not a thing we can do about it except to get through college and try, if we feel strongly enough about it, to get ourselves into a position where someday we might have some little thing to say about what's being done. Obviously, right now, there is not a darned thing we can do about it, but after college, five years from now, it will be a different story, I think.

What is this association with a bigger thing that you're talking about? Is it government or politics?

I don't look on big organizations with disparagement, the way Reisman says college people do. Being with a big corporation so you can make money and live happily - this I want no part of, because it isn't something I feel I can lose myself in. But take the U. S. government or the United Nations, they have certain values beyond themselves and each person involved is of value in terms of the whole. These people are dedicated to something beyond themselves. This is something I could give myself to.

I think you've expressed what all of us would like to do eventually, whatever we go into — be a part of something that will be a valid contribution toward betterment or alleviating the evils we see.

It is such a stupid thing to have the conditions that exist today, with talk about "overkill" and a large military force necessary to protect our country in this day and age. It's ridiculous, necessary but ridiculous. I agree that I will never be happy unless dedicated to a cause larger than myself. If I have my choice, I would rather work for some- thing besides the armed forces or NATO or anything whose basic reasons for existence are illogical and inhumane.

I feel that it is time that people who realize the problems they have to face do something about them — that they say, "I will work in government or go into politics with the hope of getting into a position where I can do something about the things I think are wrong." It's a long haul, but more people ought to be committed this way so they can have some bearing on some decisions.

Well, an alternative if you don't want to go into government is to develop a personal power. Let's say Ray gets recognized as a great writer; then what he says will mean something.

All I want to do is stand up and scream for what I believe, whether it's in my writing or in my life, whether it's, government. work or whatever it is. Regardless of the possibility that whatever I do might be completely futile, I have to do it, and if I don't then I will have lost all meaning.

I don't think there is any general despair here. However far the assertion of individuality may have fallen from vogue, that still seems to me to be the essence of amounting to anything or of being able to respect yourself.

This discussion has been so humanistic, so marvelously humanistic, that I wonder if anybody here could pull a trigger on someone.

I don't think there is anybody here who would refuse to fight if the enemy — the Russians, the Chinese or whoever — were over here storming at our doors and threatening to overthrow the country. This is just a question of survival. I'd shoot just as quickly if not quicker than the next man — or run. But I'll be darned if the army or anybody else is going to ship me off to kill Laotians.

The picture of a sergeant telling you "to fire on Cubans disturbs me — I just wouldn't do it. I can't see killing Cubans or Laotians or Koreans, or even Russians unless they are a definite threat to our well-being or our families. There a moral obligation would occur.

A lot of draftees feel that way, and I wonder how fa"r they could be trusted if they were sent to fight in Europe, say.

I don't think you can actually say that. You must realize that in every war that has been fought by a nation there have been men fighting who held the same basic beliefs that we hold here, and yet because of certain ideals, maybe presented in forms of propaganda, these men have fought and fought well, and in many cases died. I think the democratic army of the U. S. would certainly be trustworthy but maybe not serving the proper purpose.

Something that interests me is that the government doesn't seem to feel that the Peace Corps is as valuable as the Army. If a person goes into the Peace Corps they won't exempt him from the draft. There's a flagrant contradiction somewhere — that peace is not as good as war.

The importance of the Peace Corps — however the mechanics of it may work, and we could argue that till doomsday — is that it makes youth accountable for its actions. We talked about the long years it would take before we could be effective in a big organization, but with the Peace Corps we can have the feeling that what we are doing right now is of importance. All of a sudden it has come about that in our early twenties we can do something that counts. That's where the Peace Corps is of value.

We've been at this for over four hours and I guess it's time to break it up.

It's been an extremely — well — critical discussion. And I think it would be a good idea to wrap it up with some affirmation of our concern about these things, and not detached concern. The point I'm trying to make is that our talking about the College and our criticisms reflect a deep concern with it and with its basic purposes.

All of us feel a tremendous involvement here, and any criticisms and opinions and suggestions we've voiced have come out of four years' worth of involvement. It's so obvious that we've become, in part, the product of four years up here.

Bill is right, and I think it's fair to say that the way we've been talking here about the College underlines the fact that there are probably a lot of things wrong with it — but there are an awful lot of things right with it that we didn't get around to. The walls of Dartmouth are not crumbling — that's for the benefit of the alumni.

I'll second that and say that Dartmouth, despite the criticisms we've made, is a better place than it's ever been before, in terms of the education one can get here.

When we don't have any critical license, that will be the time to worry.

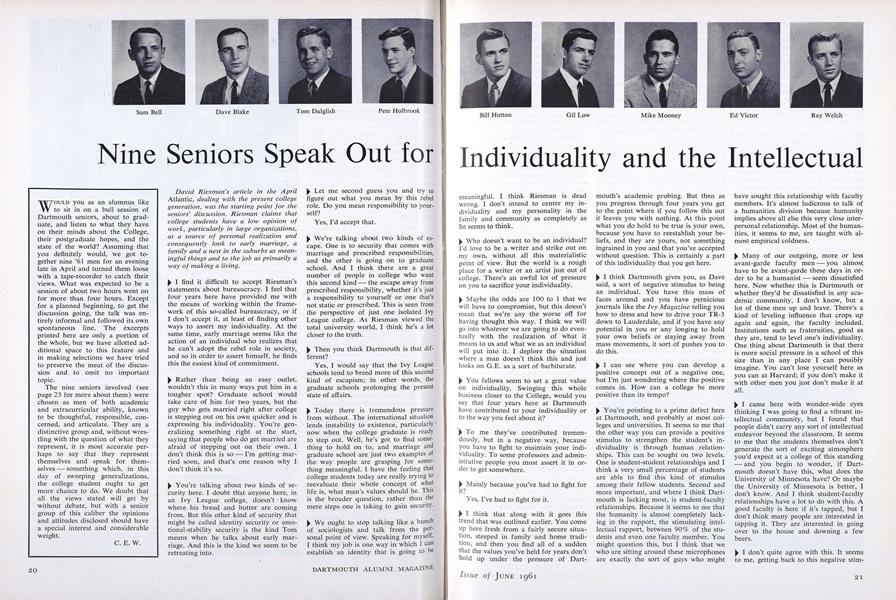

Sam Bell

Dave Blake

Tom Dalglish

Pete Holbrook

Bill Hutton

Gil Low

Mike Mooney

Ed Victor

Ray Welch

The Dartmouth Hall steps are as popular as ever as a student gathering spot.

An intellectual discussion at Sanborn House? It could be that, or maybe Green Key dates.

Fraternity Hums in May are a tradition strongly supported by today's students.

Steel framework of the Hopkins Center forms a backdrop for softball on the campus.

Today's undergraduate keeps himself well posted on the news, and as the expression above indicates, it's a very serious business.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePacifism and Other Issues: A Survey of 1960 Attitudes

June 1961 By E. PETER STARZYK '60 -

Feature

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureAn Impressive List of Honors

June 1961 -

Feature

FeatureSix Professors Retiring in June Comment on Students of Today

June 1961 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

June 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleRetiring Tea ...

June 1961

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTenure

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

FEBRUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

FeatureGood Teaching: A Case Study

February 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureFarewell Dear (BOOZY, BRAWLING) Davis

January 1976 By ROBERT SULLIVAN