As a teacher lam concerned with the attitudes of undergraduates toward academic learning and with their hunger for intellectual growth by means of dedication to the discipline which I profess. As an alumnus, however, I have interested myself in the mores of these same individuals when considered as a group of fellow human beings resident in the local Dartmouth community. Long ago I gave up trying to decide which of these two aspects of student life deserved more of my time. The awkward result of this division of interests is that I can say all I know about both of them in embarrassingly brief compass.

I believe that my students are more intellectual than my classmates. Such a statement, which I have often made to both groups, shocks neither group; in fact, it seems to please both of them. Apparently my students take their intellectual superiority for granted, assuming that it is a result of increased competition for admission to the College. My classmates on the other hand merely shrug this discussion off with the remark that mere scholastic intelligence isn't worth much. Here, I award the decision to my students.

My classmates keep on repeating that the present student body has lost its unity, because nobody knows the other guys on campus anymore and nobody even wants to. This fellowship, they insist, must at all costs be preserved because it is the vital essence of Dartmouth. My students retort that such an attitude is a form of senile romanticism, that the increased size of the College and the automobile have made some changes in the mores of the campus, but that not much harm has been done to Dartmouth unity. Which side is right? In this debate, I give the award to the old-timers.

This ties the score with one tally for each side, but the game is not over. Obviously the only thing that matters is: who's going to win, my classmates or my students? Now there's a question which I have put through my personal computer again and again with the result that I have a belief which amounts to a conviction. Who's going to win? We are.

IT seems to me that Dartmouth students, since the end of World War II, are perceptibly different from the men who attended this college thirty years ago. Not only are they better prepared generally, but they have a more serious attitude toward their studies.

Then too, the present generation seems more mature, more sophisticated, possessing a wider background (especially in European travel), probably more conscious of direction and destination than formerly.

In more recent years, the tempo of the college experience has been accelerated, owing, in part, to the pressure of the three-term curriculum and to the demands of the graduate schools for clearer evidence of scholarship for admittance to their halls. Grades today have a purchasing power as never before in our highly competitive society.

Doubtless, our Country's repeated embarrassments internationally over the past fifteen years together with the uneasiness created by the "cold war" have had a sobering effect on the student of today. He is conscious that the world is in conflict and turmoil; that he is, somehow, right in the middle of it; and that his team, democracy, has never been in such grave peril. World events are a part of him as never before. The earlier carefree days are less in evidence.

At this momentous period, we have young men at Dartmouth who, in the main, are deadly in earnest, and deeply concerned; they are alive, alert, interested, hard-working, and it is an inspiration to work with them.

MY Dartmouth career divides neatly at 1940, twenty-one years on each side. But I should not compare before 1940 with all the years after it because 1940-1950 was the abnormal decade of the Navy and the veterans. So hereafter I shall call 1919-1940 Then, and 1950-1961 Now.

Then, many more types: the woodsman, the aesthete, the earner-of-his-own-way, the rah-rah boy, the burly inarticulate athlete, the politician. Now, many fewer types: the hard worker, the loose hanger, now and then the beatnik.

Then and now, every type became an individual if you knew him well enough.

Then, the grousing at food in Commons. Now, the grousing at food in Thayer.

Then, accents: Vermont, Mid-western, Boston, Brooklyn, etc. Now, everyone speaks alike except a few Southerners.

Then, fewer student cars and more accidents. Now, more student cars and fewer accidents.

Then, Undergraduate rudeness and bad manners were common. Now, undergraduate rudeness and bad manners are rare.

Then, the undergraduate who had seen much of the world was rare. Now, even freshmen have often traveled more widely than their teachers.

Then, the like-minded tended to organize in clubs, and each fraternity seemed made up of the same kind of people. Now, organization of all kinds is regarded with suspicion or light loyalty, and fraternities have almost no character.

Then, very little interest among most undergraduates in classical music, abstract painting, avant-garde literature, ballet, opera. Now, wide-ranging and eclectic interest in all the arts at all undergraduate levels.

Then, peerades. Now, road trips.

Then, most undergraduates were proud of Dartmouth's maleness. Now, most undergraduates seem to believe Dartmouth's maleness is a defect.

Then, Hanover was a man's town except at houseparties. Now, Hanover is a man's and woman's town every weekend.

Then, more prejudice, less tolerance, and less uniformity in belief. Now, less prejudice, more tolerance, and more uniformity in belief.

Then and now, Hanover is a supremely interesting place to live.

EVEN a hurried opinion about the Dartmouth student demands a little searching of conscience if it is to be at all discriminating, particularly if it comes from a professor on the threshold of retirement. My rummagings for evidence must go back to the years when my energies and relative abilities were steadily provided with what I considered stronger incentives. Latin-American civilization, my particular subject, was then in the public eye and enjoyed a measure of academic recognition. A wider association than until recently with larger groups of students in the classroom and, outside the regular courses, in Ambas Americas, a Spanish-American club that I had organized, gave me the opportunity to get acquainted with their qualities in a broader perspective.

On checking off my own recollections, I realize how much the Dartmouth student has worked himself into my subject and in what a variety of forms he emerges in my daily teaching. I have learned from him to admire American youth in some of its most engaging facets. To him and to his levelheaded ways I owe several decades of unruffled classroom work without an unpleasant breach of discipline. The memorable faculty-student trips arranged by the Dartmouth Outing Club, now unfortunately outdated, were a quiet demonstration to the elders of the active virtues of character and unobtrusive leadership in the younger generation.

A reference to these particular attributes of the Dartmouth man, so obviously on the positive side, might be taken in the present circumstances as mere indulging in sentimentality. And so it might well be, but for me it foreshadows a large question, a sort of force majeure for the college education of the future; how will this human material, so auspiciously endowed, be shaped into the transcendent citizen-leader that a world in revolution seems to exact of this country? I cannot go beyond the formulation of the question, but whatever its forebodings, I have faith that the Dartmouth man will loyally play his part as in the centuries gone by.

LIKE many well-meaning softies of my generation who were i brought up to believe in the humanistic rather than in the utilitarian values of a college education, I am inclined to be irritated by the triumph of statistics over personal opinion. Nevertheless, I always find myself as willing as the next man to gloat over the facts and figures pertaining to our present crop of undergraduates and to believe they are much more significant than the casual impressions of any teacher could be. All readers of this magazine know by now that measured by scholastic aptitude tests and actual academic achievement, the average Dartmouth student today stands head and shoulders above his predecessor of the '20s and '30s as astudent. It would be strange if we were not getting more brainy and gifted students than we used to, if more of them were not going on to the better graduate schools, and if statistics did not reveal a steadily rising index of worldly success among our younger alumni.

The greatest problem confronting the College now is not how to attract better students but how to get and keep a faculty good enough to give students we now have a decent run for their money. Good students seem to be in abundant supply and good teachers scarce.

A man who has chosen to teach for his living cannot be a wholly reliable judge of students because of the peculiar nature of his personal attitude towards his profession and his students. Without intending to be facetious I might say that asking a retiring teacher to compare the undergraduate of 1961 with his counterpart of a generation ago is actually something like asking an elderly cow for her impression of her latest calf as compared with those she best remembers before the herd was improved by magic ministrations of artificial insemination and improved scientific feeding. I am afraid I am irretrievably bovine in this respect, for I cannot, in all honesty, say that Dartmouth undergraduates today seem to me one whit better men as a group, or more worthy of remembering as individuals than those I had the privilege of knowing and teaching back in the 1920s - whatever the cold statistics say as to their superior intellectual capacities and accomplishments as students.

DEAR MR. EDITOR: YOU ask me to compare Dartmouth students now with those of thirty years ago.

I find this a most difficult, indeed an impossible, assignment. The "then" has, of course, become nebulous with the flow of years. The present is by no means clear, even when limited to Dartmouth students and their multifold capacities and attitudes. One conclusion is certain: human nature, in students and other persons, has changed very little, if at all, over this period.

Students, and faculty who presumably also are students, cannot be dissociated from their academic and social-political environment. The radical changes in this environment seem not to have engendered any great spiritual awakening, or deep dedication to the saving of Western civilization or to the preservation of our own form of government.

Two aspects of education are now more certain: we are more concerned than formerly with the drawing out, the development of capacities; and more people are aware that no one knows everything about anything. These are helpful attitudes.

I think it was Socrates who advised his listeners to inquire - to examine, to investigate, to pursue. We have recently begun to take this advice more seriously. I am sure many facets of life will be illuminated by this process, although perhaps few, if any, with absolute finality.

ALBERT L. DEMAREE, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

JOHN B. STEARNS '16 DANIEL WEBSTER PROFESSOR OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

BENFIELD PRESSEY WILLARD PROFESSOR OF RHETORIC AND ORATORY

JOSE M. ARCE, PROFESSOR OF SPANISH

CHARLES W. SARGENT '15PROFESSOR OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, TUCK SCHOOL

ARTEMAS PACKARD, PROFESSOR OF ART

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

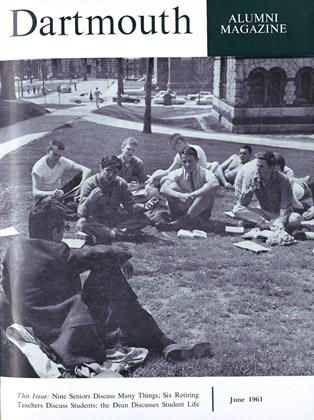

FeatureNine Seniors Speak Out for Individuality and the Intellectual

June 1961 -

Feature

FeaturePacifism and Other Issues: A Survey of 1960 Attitudes

June 1961 By E. PETER STARZYK '60 -

Feature

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureAn Impressive List of Honors

June 1961 -

Feature

FeatureSix Professors Retiring in June Comment on Students of Today

June 1961 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

June 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42