By Neal W. Gilbert '48. NewYork: Columbia University Press, 1960.255 pp. $6.00.

In these scholarly studies in the history of ideas Mr. Gilbert is primarily concerned with controversies about method in the six-teenth century. As he points out in the introduction, a person may misdescribe the method that he uses in his investigations, and so it is necessary to distinguish questions about the method that he in fact uses and the method that he may describe or recommend. Gilbert limits his studies to questions of the second sort, examining various "methodologies" or explicit views about the method to be used in acquiring knowledge.

In the first part of the book, he gives an etymology of the term methodus and surveys the ancient and medieval sources of Renaissance views. In the earlier methodologies, he discerns two traditions. "Artistic methodology," fathered by Socrates and fostered by Aristotle in the Topics, is concerned with the teaching of the arts and with communication in general. "Scientific methodology," associated with the Posterior Analytics, stresses criteria of strict proof or demonstration. Applying these categories to Renaissance writers, Gilbert includes among the partisans of artistic methodology Melanchthon, Peter Ramus, Aconzio, Girolamo Borro, and Temple. On the side of scientific methodology are, among others, Viotti, Schegk, and Zabarella. Others, Carpentarius and Keckermann, are placed in both traditions.

From his examination of these philosophers and scientists, Gilbert draws several general conclusions. In the controversy between the artistic and the scientific methodologists, neither side was right, and neither entirely wrong. Attempting to provide ways of making difficult subjects available to students, the artistic methodologists had a worthy ideal. So, too, the scientific methodologists are to be commended for their efforts to make explicit the criteria of demonstrative argumentation. Yet both sides failed to see that, since their ends differed, their proposals of means were not necessarily incompatible. Arguing against suggestions made by Cassirer and Randall, Gilbert also concludes that sixteenth-century writers on method failed to recognize the importance of experimentation and that their methodological prescriptions had little or no influence on scientific investigations. Finally, comparing them with Bacon and Descartes, Gilbert concludes that in general, turning to the past for instruction, they lacked originality. None the less, he goes on to say, they set the stage for the original and more important accounts of method in the following century.

In these studies Gilbert has chosen to limit himself to writers who "used methodus in its Renaissance senses." As a result, better known figures like Copernicus, Suarez, Pomponazzi, and Patrizzi are absent. Within the limits imposed, however, Gilbert has done a very careful and good job. His book will be required reading for Renaissance scholars.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

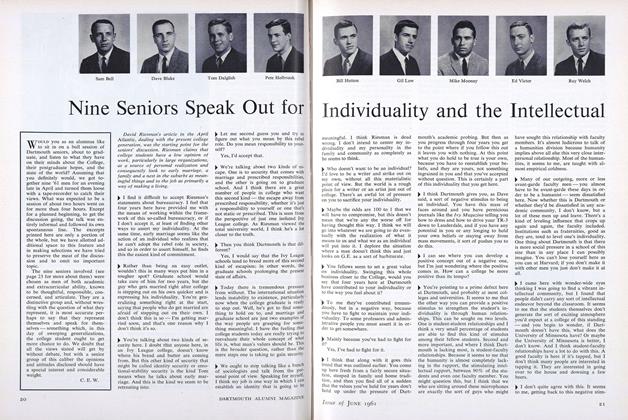

FeatureNine Seniors Speak Out for Individuality and the Intellectual

June 1961 -

Feature

FeaturePacifism and Other Issues: A Survey of 1960 Attitudes

June 1961 By E. PETER STARZYK '60 -

Feature

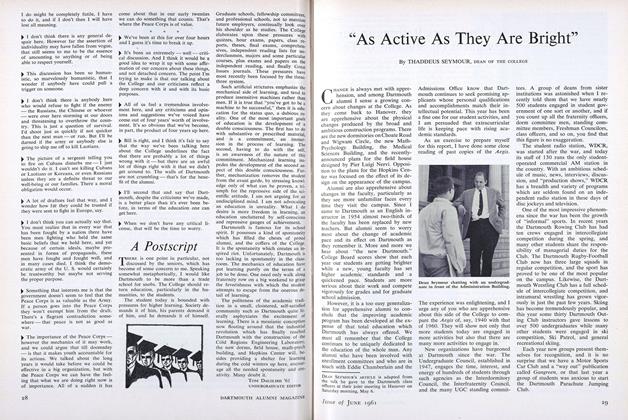

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureAn Impressive List of Honors

June 1961 -

Feature

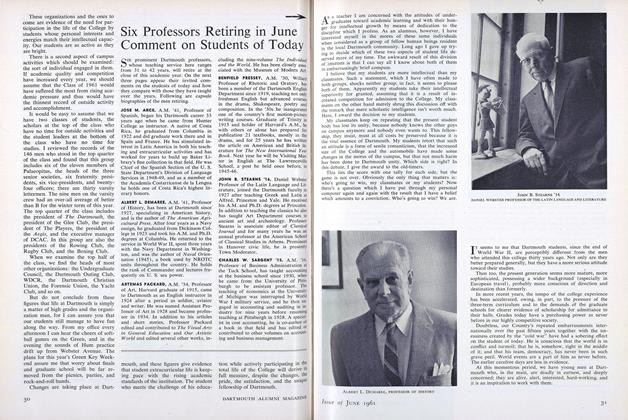

FeatureSix Professors Retiring in June Comment on Students of Today

June 1961 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

June 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42

Books

-

Books

BooksTREATMENT OF BREAST TUMORS

MARCH 1959 By GEORGE A. LORD '30, M.D. -

Books

BooksSplendor

MARCH, 1928 By H. B. Preston '05 -

Books

BooksTHE SOCIAL FUNCTIONS OF EDUCATION

May 1937 By Irving E. Bender -

Books

BooksPrinciples of Money and hanking

JANUARY, 1928 By R. V. Leffler -

Books

BooksE. E. CUMMINGS.

JULY 1964 By THOMAS VANCE -

Books

BooksAMERICANS AND CHINESE COMMUNISTS, 1927-1945: A PERSUADING ENCOUNTER.

NOVEMBER 1971 By WILLARD PETERSON