University Students of Latin America, Important as Future Leaders, Are Being Lost as Friends Through Our Failure to Communicate U.S. Ideals

WHEN, as a result of the Caryl Chessman case and the U-2 incident, the university students in Latin America were in an angry and aggressive mood, any American in their midst was certain to be the beneficiary of a varied education. Such was the atmosphere when I arrived at the National Law Faculty in Rio de Janeiro to conduct a research project on the functioning of the Brazilian judiciary system. In a sense they were favorable circumstances, for one can hardly imagine the extent to which we Americans have failed to communicate our beliefs and intentions to the rest of the world until he has had the opportunity to lecture to anxious and articulate audiences such as those I faced in Brazil.

The Latin American university student mirrors the tormented society in which he has grown to maturity. Outwardly he is dogmatic and confident; inwardly the naked emotions, bared of their sophisticated trappings, reveal the morass of confusions, doubts, misconceptions and myths on which he must rely to form his opinions. These students are already a power in their society, and the American exchange grantee quickly realizes that communications between our societies have gravely deteriorated.

Outside of their studies, parallels between the Latin American law student and his counterpart in the U.S. are few. Rarely does the Latin American law student devote full time to academic work, even when he has no other constructive diversion besides going to the university. And regardless of his interest in his studies, his overriding preoccupation, and frequently his principal occupation, is practical politics.

To these young people politics is far more than a diversion or extracurricular activity. Living in a society where, due to the low level of life expectancy, the children predominate, the young university student occupies a strategic place in the intellectual and political life of his country. Of 52 million inhabitants of Brazil in 1950 (the 1960 census registers 70 million but is not yet available in detail) the adult men of 24-80 years numbered 9,900,000. Young people under 24 years of age accounted for 32,000,000. Discounting the more than 50% illiterate and semi-literate, about four million mature male adults, not many more than in the metropolitan New York area, remain to teach the young and conduct the affairs of a nation geographically larger than the continental United States.

In this environment, the law schools are notoriously the most radical and active. Unlike the student in the United States, where law study is graduate work intensely pursued for three years after exposure to a liberal college education, the Latin American law student arrives in law school directly from high school. Still possessed of the fervor and enthusiasm of his adolescence, he embarks on five years of a leisurely and almost exclusively legal curriculum. A natural precursor to politics, law is also the easiest and least expensive field of higher education. Since home assignments are a rarity, it is one of the few degrees which can be pursued while holding down a full-time job. Consequently it is the most accessible to the poorer students, who are at the same time younger yet more deeply involved in practical affairs than their North American contemporaries.

DURING my year with the Brazilian students, it became readily apparent that the gravest challenges to the Latin American democracies do not emanate from the convinced, doctrinaire Communists. Few of the students I met even began to understand the meaning of a communist society or had thought through in more than a superficial manner the application of the communist ideas. The challenge rose from the overwhelming number of concerned young people who have sought refuge in the communist camp through lack of any alternative. The accurate characterization of this vast mass of young people is anti-misery, anti the arbitrary suffering that daily parades before their eyes. Located in the principal cities where the extremes between poverty and wealth are none too subtle, badly housed and fed themselves, these young, ambitious students constitute an active and perpetual group of malcontents. Their consuming determination to advance a social order based on principles •of justice is rivaled only by their selfconfidence in their own abilities to be the intellectual leaders of that society.

On the whole, these students are unquestionably expressing honest cries of indignation and independence. They may express themselves untactfully at times, but - and this point must be emphasized - they are not a basically destructive group. If their desire to improve the condition of their own society has been manifested in anti-American sentiment, this is the product of at least two forces which have been relentlessly conditioning them for the last decade: unceasing hammering home by the Communists of the idea that the lack of economic development can be blamed on U.S.-designed or inspired policies, and the seeming unconcern of Americans in anything except protecting their own private investments.

The basic question which we must squarely face is why, at this time, these students have finally succumbed to these arguments. When for 150 years before World War II they instinctively looked to the U.S. for guidance and inspiration, why have they suddenly turned in other directions for leadership? Essentially, why has the U.S. failed to communicate to these young people a clearer view of her aims and objectives?

So fundamental and intricate is the principal reason behind their craving for change, any change, that I must beg the liberty of omitting its discussion in this article: this is the arbitrary injustice of their social and economic conditions. The subject has been treated frequently. At the risk of oversimplifying, I would like to suggest three other reasons for our inability to communicate with them. These are: (1) their need for a panacea, (2) a serious confusion of differing ideas, and (3) the obvious but astounding failure of the U.S. to impart a more honest and representative picture of life in this country.

Youth is inevitably drawn to a panacea. The more idealistic they are, the more they demand immediate perfection. Human nature, trial and error, slow evolution have little place in their thinking. Given these conditions, any government designed to give vent to all expression is continually suspect, and generally the suspicion is of policies that haven't the vaguest relation to official policies.

This milieu offers the Communists an initial advantage which is difficult to overcome unless one has the time to analyze their assertions and recast them in proper context and perspective. The Marxist arguments are almost hand-tailored to cater to youth's needs. They are simple, palpably scientific and logical; they "know" and proclaim in clear and forthright language the responsibility for the problems of Latin America. Their explanations are easily understood and, most important, least damaging to the young man's own self-respect. What more suitable scapegoat could be unearthed than the fat Yankee imperialist, sucking the life blood from the people for decades, corrupting the government, and preventing the masses from lifting their heads. Thousands of idealistic but anxious and malleable young people, living amidst arbitrary and apparently static squalor, are lured to the "logical" analysis; an even greater number are able to find in it an aggressive release, a justification for belligerent anti-American attitudes.

The most striking instance of how the imagination of the young people is captured by the image of a panacea is the impact made by Communist China. More than any other single event, the intelligence and determination portrayed in the well-publicized "progress" of the Peiping regime has furthered the cause of communism among the students. In one discussion a student candidly told me that what America achieved after 200 years did not excite him. What China did in ten years does.

We, in our college classrooms, easily refute these arguments; but they are not so easily refuted among those who have known only failures of free enterprise. One time I tried to pin down what it was, assuming their suppositions about China to be true, that has caused this progress. After much banter, a few students reluctantly admitted that no "ism" per se made the difference. Communism employs no secret method, has no monopoly on the one thing that enables a society to gain sufficient resources to attend to the welfare of its citizens; it is work. If the Communists systematically put the people to work, the same can be done within a free society. Only we must find the means to encourage the will and incentive to work whereas a communist

regime, once it assumes control, asks no questions and offers no way out. Nonetheless, their conviction that a free society may never be able to meet this challenge remained basically unshaken.

The students' attitude was explained by one young professor as clear evidence that communism, to these youth, is not doctrinaire thought in terms of Marx and Lenin. It is an idea of an efficient business organization capable of mobilizing the human and natural resources of the society and producing material benefits. The student seeks only tangible economic progress and has little attachment to any philosophical system except to the degree that it promises this progress.

AN important factor in the communists' success is the inability of the students to cope with the pat solutions that are presented to them. Understandably, the conditions under which they live do not encourage a thoughtful analysis of capitalism's failures. It has failed; that is all. Furthermore, it offers no tangible plan against which the Communists' assertions can be measured. Compounding the dilemma is the technique of Latin American education, so excellent in its social-minded and humanistic approach to world problems, inculcating an awareness and inciting the anxiousness of youth for their solution. Derived from the European systems and emphasizing the "memorizing" method, however, the educational system is weak in providing the tools and techniques of deep and thoughtful analysis. Thus, more often than not, the students are sitting ducks for the Communists' soul-searching, heart-rending appeals, inevitably phrased with, "Is it justice that. .."

I cannot count the number of times a student would stop me to relate arguments he had heard, asking, "What can I say?" "Is it true?" They were thirsting for ideas and arguments to refute propositions they sensed to be unfounded but were powerless to combat. No access to these arguments was available as effortlessly as the leftists make theirs. We and our Latin American friends have failed to provide and circulate the information that offers the perspective needed to battle the panacea, and gives youth confidence that their problems can find a solution within the framework of a free society.

The second factor contributing to the success of the Communists with Latin American students is the vague and blurred lines drawn between differing political philosophies. One can hardly identify the political beliefs of a student, so confused and ill-defined are the lines. What is a natural human weakness is here carried to extremes. For example, nationalism is frequently undifferentiated from communism, resulting in the amalgamation of two philosophies which are theoretically pole's apart. One repeatedly hears the "ideals" of a communist society uncritically equated with the concept of a good life without considering the practical realities of the materialistic, regimented society that has to date resulted from such regimes. Free enterprise invariably connotes foreign capital dominating and exploiting the society, depriving the people of their rightful wealth and resources. In the emotionally charged atmosphere little thought is given to what may have been the real causes of the power of foreign capital or what were the alternatives to foreign capital in the past. To a harassed lecturer, this tendency to lump together a hodge-podge of differing theories, ignoring the evolution of history and approaching the problems of the world as though this generation were the first on earth, can make simplicity and clarity of response a most frustrating effort.

The Caryl Chessman case, an honest protest on the part of millions, Americans included, is an example of how confusion and distortion can be generated, with overtones of anti-American venom. Congressional investigations, which could be viewed as one of the few clear examples of the self-corrective mechanism of a free society, were manipulated to bear evidence of the venality of our system. When a Senate committee was investigating the profit margins of the drug industry, one student could only point out to me this "proof" of the "gluttony of the trusts."

Clearly, the Communist seeks to foster this confusion of issues wherever and whenever possible. Seldom has communist propaganda devoted itself to extolling the merits of communal life; it concentrates on identifying the U.S. as theprincipal cause if not the intentional designer of the hemisphere's poverty.

One of the most sobering examples of the extremes which attract some young, people was provided by one discussion I had with a group of articulate young leftists after a lecture at the Law Faculty in Curitiba. They accepted, to a fatalistic degree, the thesis that the U.S. and its. private business interests were the cause of the continent's present condition. Financial aid programs, in their opinion,, were futile and fraudulent. "Your gigantic trusts," one young man told me, "are the principal corrupting and demoralizing, influence on our people. They have so great a financial stake in our country, and no social roots in it, that they cannot help but ruin our government."

He reasoned that the companies necessarily spare no effort to make the governmental bureaucracy dependent on them, and even if some individuals controlling the trusts wanted to, this corrupting influence was beyond their power to stop, since it is an insidious and necessary consequence of the profit system. "Because of it," he continued, "our free elections have become meaningless. Our democratically elected governments may speak of progressive ideals and advance minor proposals to improve the lot of our people but never will they embark on the large-scale organization and discipline which our economy demands. Whose fault is it? Some say it's corruption within our own government; but essentially it's the reliance of our people on foreign capital to do the job they should be doing. It does not matter. The corrosive influence of your big business has completely undermined the moral values of the people in power and caused paralysis of their brains."

This young man adamantly insisted that the only way Latin America will begin to develop is to purposefully rid itself of this corrupting influence a la Fidel Castro. It can never disappear voluntarily. And indeed, he and innumerable other young men said to me, "You will never understand Latin America unless you see how thoroughly big business controls and corrupts government."

At first glance this may not strike one as a confusion of issues. But when we consider where mankind has come from, what conditions are today compared with what may be likened to the dark ages only thirty years ago, then a tragic confusion of issues becomes evident; a confusion between what might have been necessary thirty years ago to remedy the abuses he cites, and what is required today.

BUT, important as these two factors may be, a third failing is most disheartening to one who has listened to the questions and discussions of these young people. The failure to communicate a better, more representative understanding of the U.S. may well be the most important failing in the battle to gain time for democracy to solve its problems.

The widespread ignorance and misconceptions about life in modern America is often shocking. This is not to imply that there aren't many students with a deep understanding of democracy and the constant effort that must go along with a functioning and viable free society. But even these young people, many of whom are among the more intellectual of their group, harbor a certain hesitancy and reserve about admitting anything good about America. The university student of Latin America, who considers himself to be among the intellectual elite of his own society, is scarcely aware of the great number of American people who share his same interests and concern, who are just as deeply involved in the same battle he is waging, who are just as devoted as he to the ideal of helping all men achieve a life of dignity as rapidly as possible. We are simply not getting a picture of that aspect of our national life across to these young people.

Many of these distortions of American life are conceived in the inevitable tendency to generalize from extremes. These students do not have a broad view of our culture as do we who live amidst it. Naturally when they read about the poll tax, the race problem, the self-criticism of our educational system, state governors resisting federal authority, or abuses uncovered or perpetrated by Congressional committees, distortions result. The few school districts where racial violence occurs are daily conversation; the hundreds where peaceable integration has taken place are unknown.

It is easy to denounce the Communists for instigating these distortions and exaggerations. Unquestionably the seeds have been nurtured by an insidious propaganda campaign, but the ultimate responsibility rests on our shoulders; it has been fostered and encouraged by our own indifference. We have conveyed a firm impression of our material resources, relying on a temporary advantage which in itself is less important than how it was acquired. With all the money we spend on information programs, we talk to ourselves, we talk to those people who already agree with us, who are sympathetic to our point of view.

A good example is the USIA overseas libraries. While invaluable for certain purposes, they depend on the initiative of the individual to learn about America. Our adversaries and their followers are not that interested and do not frequent them. Of all the students of leftist sympathies with whom I spoke, not one had ever taken the trouble to go to a "Thomas Jefferson" library, which, curiously, is often located in one of the wealthy boroughs. Similarly we could cite our painstakingly drawn press releases, which rarely find publication in any but proAmerican newspapers, or even our visiting professors and students, who more often than not circulate among people sympathetic to their beliefs.

No single idea or program is going to remedy this state of affairs; the only remedy is a long, arduous process of trying to build up what we, in our unawareness, have already lost. Essentially, it depends on making more vigorous use of daring, imaginative and concerned people in our government-sponsored programs. President Kennedy's Peace Corps may be a wonderful opportunity. Potentially, it can do a job which no other American representative abroad, governmental, business, or tourist, has effectively done; it can enter into direct personal contact with the people and the students on all levels.

Personal contact, however, bears an inherent limitation in that it is only as good as the people doing it. I had contact with a good proportion of the exchange students who came to Brazil in the year I was there. Many of them were unable to cope with the anti-Americanism they encountered. Some openly sided with the critics as though they were back home before an audience with sufficient understanding of the American scene to put their criticisms into perspective. Needless to say, this frequently engendered more confusion and doubt than existed before they came. Not that we need to inhibit our self-criticism; but we must be awake to the misconceptions and distortions that emanate from an unbalanced picture.

We can no longer rely on the intuition of the Latin American people to realize what America is doing in the world today. Nor can we afford to comfort ourselves by calling the Communists names. Everyone knows we don't like Communists. Secretary Rusk has warned that "our problems will not be scolded away by invective or frightened away by bluster." Such talk may be reassuring to those who are already on our side, but it does little to convince those who oppose us.

It is time we began to speak out, loudly and firmly, for what we do believe in. These young people may be anti-intervention, but they always appreciate a good argument. They ask only for a firm, purposeful and progressive ideal capable of inspiring and mobilizing a developing society. One young student bluntly explained his dilemma to me. "Your books and professors say one thing, and the Americans we see here do another. I think if you begin to practice what you preach to us, you will not find us difficult to get along with."

And most revealing was a series of indignant questions thrown at me by one student on the subject of Fidel Castro. "O.K.," he said, "if your country doesn't want us to believe that Fidel is a great leader of his people, who do you want us to look up to then? The men who presently run our government and continue to let our people live in squalor? Show us something better to believe in. Then we will listen to you."

They will listen. But they crave answers that are directly relevant to their experience and needs. We cannot expect the student miraculously to become endowed with insight. Someone must help him to learn and the one who helps is the one whose ideas he is most likely to adopt. We have long neglected our communications with the students of Latin America. This is a self-indulgence we no longer can afford.

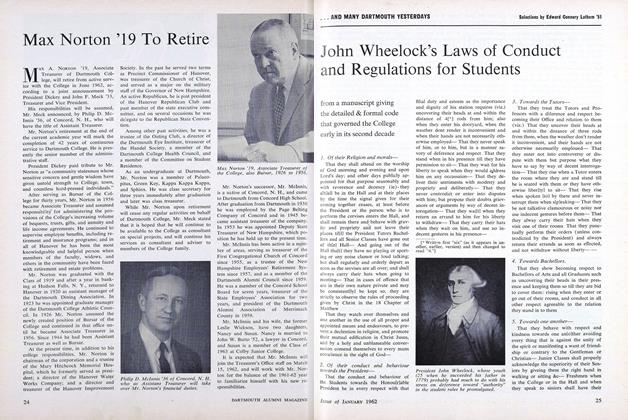

University students in Mexico City staging a riotous demonstration in whichprompt police action thwarted their effort to burn the United States flag.

Wide World PhotoAnother anti-American demonstration by students, this one in Santiago, Chile,supporting Castro and protesting the visit of UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJohn Wheelock's Laws of Conduct and Regulations for Students

January 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SKIWAY

January 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Erickson-Bismarck Plan

January 1962 By EPHRAIM ANIEBONA '64, ' AMIN EL-WA'RY '64 -

Feature

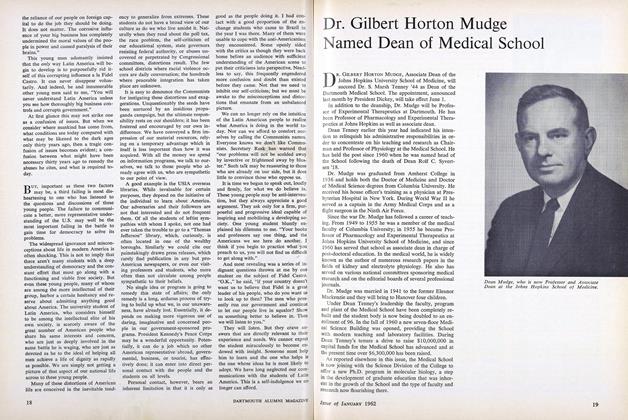

FeatureDr. Gilbert Horton Mudge Named Dean of Medical School

January 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

January 1962 By , STEWART SANDERS, JAMES L. FLYNN -

Article

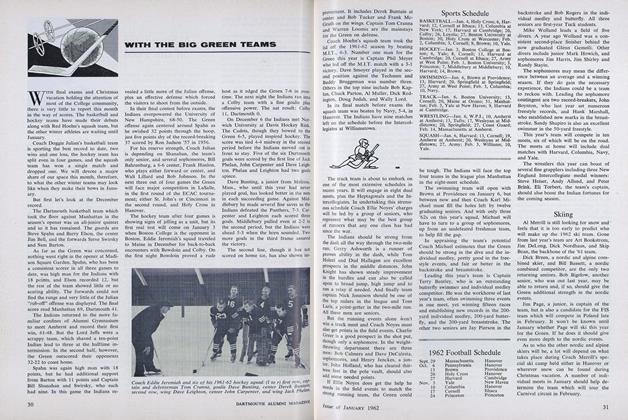

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

January 1962 By DAVE ORR '57

Features

-

FEATURE

FEATUREHat Couture

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By HEATHER SALERNO -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

FEATURE

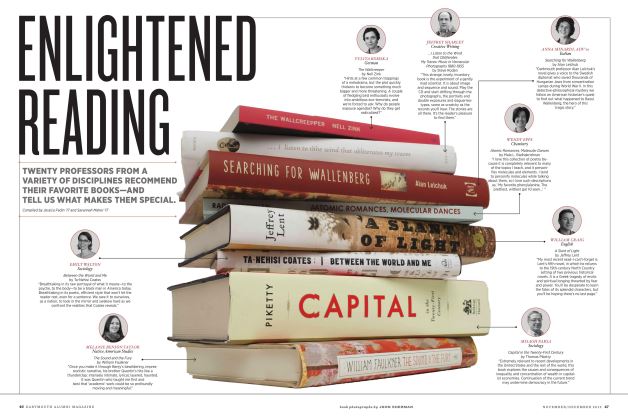

FEATUREEnlightened Reading

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By Jessica Fedin ’17 and Savannah Maher ’17 -

Feature

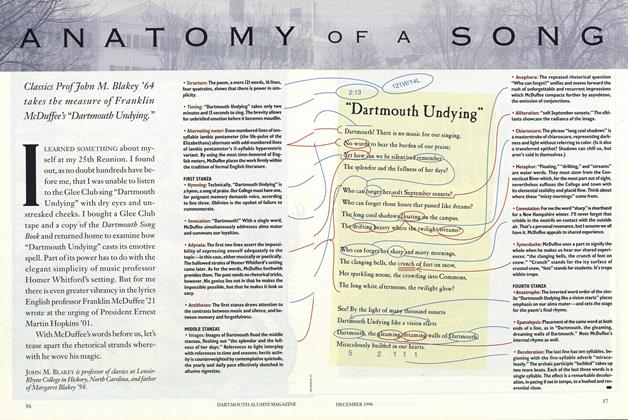

FeatureANATOMY OF A SONG

DECEMBER 1996 By John M. Blakey '64 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

NovembeR | decembeR By REBECCA BURTEN ’16/THE DARTMOUTH -

Feature

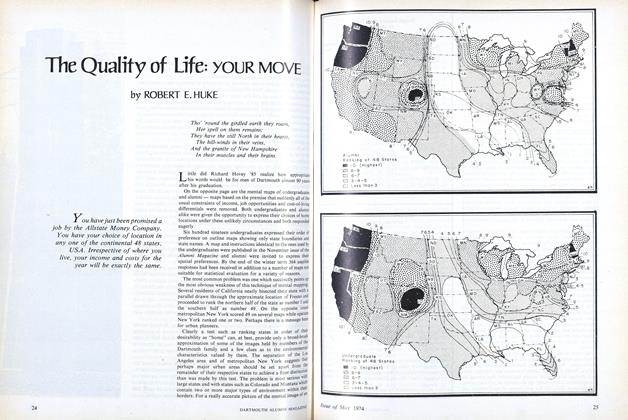

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

May 1974 By ROBERT E. HUKE