How do you prepare young people for lwo Jima and Hiroshima?

Faculty dean James Wright was, Acting President when he addressedthis question to the Class Officers in May. The occasion coincided with the 50th anniversary of the conclusion of the War in Europe. Wright noted that his speech also took place 'while the class of1999—the last class of the millennium—was receiving its acceptance.letters;At the same tirtie, the class ofl94s:Wasab6ut to hold its 50threunion, andthe class 0f 1970 its 25th.

Wright spoke to a group representing classes ranging from1924 to 1995. "In this room are lifetimes of experience and lifetimes of expectation," he told the group. He noted that "institutionslike Dartmouth learn from the experiences of those who have comebefore. And the main lesson that we can learn from the past is howunexpected and surprising the future will be. "

The text below is adapted from his comments.

THIS IS A TIME OF REMEMBERING: remembering 50 years ago when U.S. and Russian troops met in the rubble of the thousand-year Reich; remembering the Holocaust and all of the horror it revealed; remembering Kent State 25 years ago: remembering the last American helicopters hurrying from Saigon just 20 years ago.

Dartmouth men spanning nearly half a century fought inthe Second World War. Members of classes ranging from1902 to 1950. Two hundred thirty-four of them lost theirlives in places like Guadalcanal, Salerno. Normandy, and Okinawa. War is about more than numbers and casualty lists,though, and it is about more than place names far away. War is about principle and ideal, it is about vifciousness and;violence. It is about youngsters being asked to do unpleasant things. It is about deaths too young and lives not lived.

During World War II, many wondered even at Dartmouth about the relevance of a liberal-arts education in a world so cruel and so crazy. But President Hopkins consistently demanded that the liberal arts were the purpose of the College and that that purpose was the best hope for a saner world. Military training had to be temporary and transient. From the fields of France, Ralph Hill '39 wrote late in the summer of 1944 his response to those who questioned the meaning of the liberal arts in this world of destruction. He said that the critics needed to "'know that something from the past is fortifying our little group from doubt, fear, and even disillusionment. If they are interested, I can tell them for what Dartmouth mouth helped prepare me." His answer was simple: "Normandy." mandy."

Last June, in the most moving Commencement address! I have had the privilege to hear, Jim Freedman reflected on what he had learned from his experience with cancer. He explained that while there is no wholly adequate preparation for life and its challenges,::a liberal education was the best preparation available. And so many have learned.

Obviously those who came back from the war were changed by their experience. Dartmouth, after the war, was a different place. Many veterans returned to complete their studies and to graduate, but asjoe Medlicott '50 said, "It was tough to wear beanies and wrestle in the mud if a year earlier you were flying over Tokyo in a B-29." Those of us who are the children of the World War II generation know well the seriousness of our fathers.

Mr. Dickey consistently reminded each student who joined in this community that we did have a broader set of responsibilities, that we were our brothers' keepers, and that we had international obligations. War and force, he said, were not the answer to problems; they finally represented the failure of answers.

In World War II as in Korea, purposes seemed clear and objectives were shared. Vietnam was a different matter. Ted Beal '62 has said of that conflict, "We were on every side of that issue in our class And we're not talking intellectual arguments. We're talking pretty serious differences."

Twenty-five years ago, on May 5,1970, President Kemeny called off classes, following the shootings at Kent State on the previous afternoon. Here, perhaps, the intersecting paths of Dartmouth's history lose their linear predictability. During; the Vietnam War Dartmouth students and graduates hunkered down at Khe, Sanh and walked patrol at Nang. Dartmouth students also occupied the president's office in Parkhurst Hall and participated in marches on Washington. The divergent paths are complicated, and this is no place even to begin to analyze them. Suffice it to say I would argue that each of the paths could be considered a natural product and result of the liberal-arts education provided here, of the principles articulated and lessons learned in the post World War II years. Moral purpose, commitment to principles, courage; and, yes, sacrifice marked each of the paths. Until we can honor those who died at Kent State and at Khe Sanh, then we will not be able to put this trauma behind us, and I submit that it is time for us to do so.

Now we welcome members of die class of 1999, most of whom were born in 1977. Kent State and Khe Sanh were not part of their lives, let alone their memory.

But our business here is their future and not our past. The class of 1999 will return for its 25th reunion in the year 2024 and its 50th reunion in 2049. And if Dartmouth of the Vietnam era and before was all-male, and soldiers almost exclusively male, such is no longer the case. How do we prepare them, women and men. for the lives they will lead? Will their lives be more peaceful or less violent than those of the last 50 yers?

Here history can only guide; it is not a recipe or blueprint. There is no curriculum that can prepare students for the horror of Buchenwald, the sharp coral beaches of Iwo jima, the rubble of Berlin, the desolation ot Hiroshima, or the sheer horror of My Lai. How can you directly prepare anyone for the suffering of Bataan or of Korea's Chosin Reservoir—the "Frozen Chosin" as marines remembered it?

At our best we are teachers, not prophets. As I reflect on my first year at Dartmouth, 25 years ago, and on the class of 1970 and all that has happened since, I wonder what I might then have encouraged them to study had I known all that I know now. For certainly the world has changed and it has changed significantly. If I had known it all, how would I have prepared them for the complicated forces of their lives?

Some of my students would soon go to Vietnam. How to prepare them for that?

How to prepare them for the Arab oil embargo and the fundamental changes that have marked international trade and American economic dominance over die last quarter century?

How to prepare them for the advances in science and technology that were only hinted at by the landing on the moon?

How to prepare them for the major shifts in our domestic politics—and in our diminishing expectations for our political system and our politicians?

How to prepare them for the fundamental alterations in relations between men and women and the dynamics of family life that would mark their own experience?

How to prepare them for the acknowledgment that affirmative action would not be a slogan but an obligation, and an obligation that finally would enrich us all?

I think I would have done pretty much what Id id do. I tried then, as our faculty still does, to teach knowledge but also perspective, to enhance thoughtfulness and inquisitiveness and flexibility, I think that the most we can hope for our students is that they learn to think critically and clearly, that they learn to express and defend ideas, that they learn to understand and be tolerant: of cultures and attitudes and times different from their own, and finally that they learn to adjust to change. For all we can assure them, all we can safely predict, is that change will mark their lives.' "Being prepared for change has always been one of die functions of education," said President Dickey at the 1963 Convocation. He believed that a prerequisite for effective leadership is a."capacity for being undismayed when, as happens to all of us, we come face to face with change we neither made nor foresaw—and damn well don't like."

The College has always faced this issue: how to prepare our graduates to face an unknown about beauty and creativity and human ideals, we are also preparing them for the unimaginable. that we provide relevant to the experiences that they will face?

What I can say to you is that the women and men who are the students at Dartmouth today will do us proud, as we will continue to do well by them. And I say to you, members of whatever classes, you and your classmates have done us proud, both collectively and individually. Your eixamples, your sacrifices, your commitmentinspire us ami arc part of what this is and what it does. I believe that for the privilege of being part of this special company, we all incur special obligations. We will meet these in different ways.

Dick Hall '15, one of the first Americans killed in the Great War, was not a warrior. He wrote his parents in 1915, as he volunteered to go to France, "while one would meet with much that might dishearten him, he would always have the comfort, the reassurance, of the fact that he was doing his share, however small, in helping to better the condition of others."

Dick Hall was a young man of peace who went to war, but not to fight. It is now 80 years since he died on Christmas morning, when a shell hit the ambulance he was driving in the French countryside. Perhaps 80 years after his death, his life and values offer us a powerfully symbolic reminder that it is time to put aside, finally, those differences chat divided us so sharply 25 years ago. These intersecting anniversaries cry out for us to remember and to thank those whose sacrifices were forever.

At our best we are teachers, not prophets.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

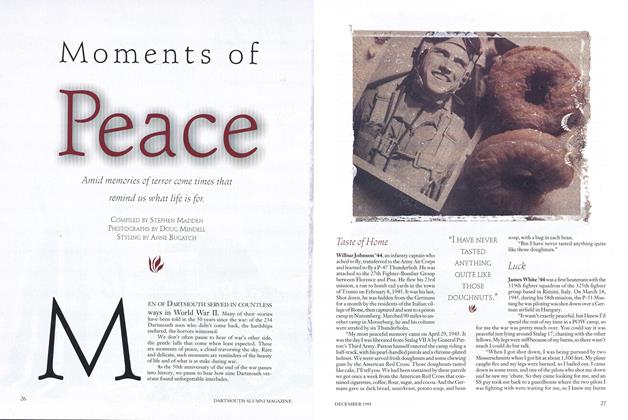

Cover StoryMoments of Peace

December 1995 By Stephen Madden -

Feature

FeatureNice Work if You Can Get It

December 1995 By DIANE CYR -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticlePreparing for Contingencies

December 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleControlling Self-Control

December 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

December 1995 By Armanda Iorio

James Wright

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

MAY 1997 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleBuilding Community

APRIL 1999 By James Wright -

Interview

Interview"We Expect Excellence"

May/June 2005 By James Wright -

Article

Article"Quite a Group"

Sept/Oct 2005 By JAMES WRIGHT -

notebook

notebookGood Neighbor

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JAMES WRIGHT

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTIMOTHY WAS BEFORE YOU

June 1955 By DANIEL CHASE '14 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

DECEMBER • 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

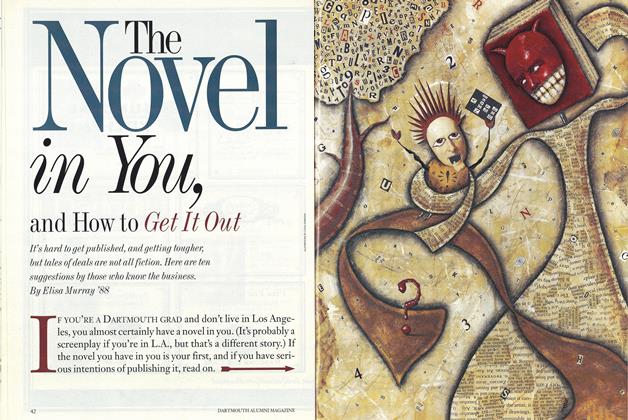

FeatureThe Novel in You, and How to Get It Out

DECEMBER 1996 By Elisa Murray '88 -

Feature

FeatureCan Investors Make Lots of Money and Save the World at the Same Time?

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

APRIL 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham