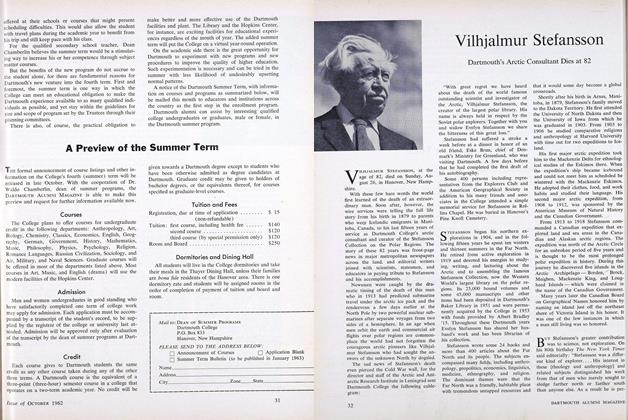

Ted Geisel '25, creator of a fantastic world for children, and adults, published his first book 25 years ago this fall.

Twenty-five years ago this fall a large, thin, blue-covered book with the strange title And To ThinkThat I Saw It on Mulberry Street was published with little fanfare by the Vanguard Press of New York. The author’s by-line was simply Dr. Seuss.

This was the first children’s book written and illustrated by Theodor Seuss Geisel ’25, and the author admits he was a bit skeptical about the juvenile field and preferred to reserve his patronym for some more serious endeavor.

This fall Random House will issue its twentieth Dr. Seuss book, Dr. Seuss’Sleep Book. An initial run of 100,000 copies will bring the total of Dr. Seuss books printed by Random House since 1937 to over five million, one of the most impressive totals achieved by any author and a record which delights both the publisher and Dr. Seuss.

Geisel had already earned a name and a living from his fanciful, distinctive drawings before he turned to children’s books. A cartoon he did for Judge showed a sleepy knight turning down his bed to find a dragon in it, whereupon he cried out in exasperation that he thought he had sprayed the whole castle with “Flit,” an insecticide put out by the Esso Standard Oil Company. This brought him a contract to do a series of cartoons for those “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” ad- vertisements which for seventeen years amused millions of readers and almost overnight created a popular public phrase.

Later on for Essomarine fuel oil, Gei- sel dreamed up the imaginary “Seuss Navy” and awarded honorary admiral’s commissions to prominent yachtsmen, steamship-line captains, and navy officers.

Returning to this country from one of his European trips in 1936, Admiral Seuss became mesmerized by the steady and powerful beat of the Kungsholm’s engines. The words that seemed to match this beat were “And to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street,” and thus was born his first book.

In a few months he pounded out the galloping verses which told the story of what a little boy fancied he saw on Mul- berry Street as he walked there daily on his way to school. Full colored drawings on each page illustrated the verses.

A chance meeting on Madison Avenue with a Dartmouth contemporary, Mar- shall McClintock ’26, then juvenile editor of Vanguard Press, brought author and publisher together. The book was an in- stant success. It has now gone through fifteen editions, has been read and dramatized on radio more than one hun- dred times, and was even used by Deems Taylor in composing “a set of variations for orchestra” which was played by the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall in 1943.

Encouraged by this success, Geisel did a second book for Vanguard, The 500Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, and has since managed to produce almost a book a year (22 in 25 years), all but three of them in verse. Each has been enthusi- astically hailed by children and parents alike, with one reviewer acclaiming Gei- sel “the Ogden Nash of the Liliputian world.” Random House now orders an initial printing of 100,000 for each Dr. Seuss volume, but even this was inade- quate for his Happy Birthday to You!, published in 1959 and sold out in a few weeks.

A modest, almost shy man, appearing much like the college professor he once aspired to be, Ted Geisel is a little awed and frightened by the success of what he terms this “logical insanity.”

Bennett Cerf, the genial impressario of Random House, calls Geisel “a genius, pure and simple.” He told us during an interview that “Ted is the nicest, most dignified, unassuming, soul-satisfying per- son I’ve ever met in my entire life • and this goes for his wife, Helen, as well.”

The Random House publisher reports that the Dr. Seuss books are intended primarily for youngsters in the five-to- nine-year range, but his admirers are of all ages. On the West Coast, for example, there are several “fan clubs” on college campuses, and there is widespread evi- dence that adults enjoy reading his books whether to children or to themselves.

One Hanover mother of three children recently remarked, “Dr. Seuss never talks down to the children. His verses are clever and there’s always a touch of real wit, a little twist that my children laugh at for one reason and we adults for an- other.”

Bennett Cerf summed it up this way: “Ted speaks a language children intui- tively understand. Somehow he’s com- pletely in tune with the secret world of childhood.”

Odd as it may seem, Geisel’s ability to write for youngsters may stem, at least in part, from the fact that the Geisels have no children of their own. Ted met his wife, Helen Palmer, who also writes and edits children’s books, while they were both studying at Oxford. They were married soon after he sold his first car- toon in New York.

We asked Ted if he ever tried out his books on children before publication. “No.” he said. “Kids don’t ever want to hurt- your feelings so they always say what they think you want to hear.”

Helen Geisel is Ted’s chief critic and editor and he relies heavily on her judg- ment, also on her encouragement. Since 1948 the Geisels have lived and worked in a pink stucco house which they built around an old observation tower perched atop Mount Soledad in La Jolla, Cali- fornia. Geisel used to work in almost any corner of the rambling house, but a few years ago, at the urging of the Random House production chief, he built on a studio and had its walls lined with cork to hold his drawings.

A painstaking worker, Geisel agonizes over each drawing and each line of verse and Helen often has to rescue them from the wastebasket. Others wind up in a “Fibber McGee” closet where, Geisel told us, he has enough material stored for at least a dozen more books.

“I dig into it occasionally,” he said, “and start working some of the material over again. Some of it can be expanded into a book, other material is shortened to a story.”

Dr. Seuss had little formal art train- ing. He started to take an art course at the Springfield, Mass., High School, but dropped it at the end of the first day.

“I’d done a sketch,” he recalls, “and had turned it upside down to check it something all good artists instinctively do when the teacher came by and criti- cized me for checking my drawing that way. I somehow felt I wouldn’t learn much from that teacher, so I left the course.”

We were chatting with Ted and Helen Geisel last June, when they were visiting in Hanover. Also on hand was Ted’s father - Theodor Robert Geisel, who for many years was Superintendent of Public Parks in Springfield, Mass. He was observing his 83 rd birthday that weekend with a spryness that belied his years.

“Ted did take a correspondence course in drawing,” the senior Geisel reported. “He came to me one day with one of those advertisements torn from a maga- zine. This one showed Uncle Sam and you were supposed to copy it and send it in. Ted did and later I gave him $15.00 to enroll in the course.”

“As a matter of fact it wasn’t a bad investment,” Ted said. “I think I picked up a lot of technical points that really helped get me started.”

How did Dartmouth happen to enter the picture?

“I had a good friend at Springfield High who planned to attend Dartmouth,” Geisel recalled, “and so I became inter- ested and finally applied. My friend never did go, but I wound up here any- way.”

As a member of the Class of 1925 (there are those who call it the Great Class of 1925) Geisel was active in campus publications, doing art and edi- torial work for the Green Book, the Aegis, and more particularly for Jack-o-Lantern, of which he was editor-in-chief his senior year.

Geisel majored in English and pays tribute to a creative writing course taught by Professor Benfield Pressey. “I don’t think much of creative writing courses,” Geisel admits, “because I think it is al- most impossible to teach anyone how to write, but Ben Pressey’s course did help me.”

The Geisels still keep in touch with many of the Dartmouth men he knew as an undergraduate, and on frequent visits to Hanover they get together with friends like Ford Whelden ’25, Larry Leavitt ’25, and Don Bartlett ’24.

Bartlett, professor of biography, is one of Ted Geisel’s closest friends. The two met as undergraduates but became much better acquainted when they roomed to- gether at Oxford University in the spring of 1926. They kept in touch over the years, then met during the latter days of World War II when Bartlett was with the Intelligence Department in Japan as a specialist and Geisel came to Japan to make a film. “They don’t come any better than Ted,” Professor Bartlett says. “He has a wonderful sense of humor and is always fun to be with.”

Professor Bartlett still shudders when reminded of a visit the Geisels made to Hanover in 1958. On that occasion some- one organized about 100 Hanover young- sters who dressed like Dr. Seuss char- acters, turned up in front of the Hanover Inn as a reception committee, and then paraded the shy and bewildered Dr. Seuss around the campus in Dean Thad- deus Seymour’s old Packard Phaeton.

Kids take naturally to Dr. Seuss, and he doesn’t mind accommodating them for autographs and handshakes at the ap- propriate time, but they can get out of hand sometimes. Bennett Cerf described an autographing party at a downtown Detroit department store where the mob of youngsters got so large that the only way they could get Geisel away for an- other appointment was to airlift him by helicopter from the roof of the depart- ment store.

Professor Bartlett also told us about the one and only oil painting Ted Geisel ever did. It was a large (five by seven feet), humorously bawdy painting of “The Rape of the Sabine Women” and for some years it hung behind the bar of the Dartmouth Club in New York. Then, during renovations and the Club’s move to the Commodore Hotel, the painting was stored in an old loft and somewhat damaged.

Recently it came to light, and this past June when he was in Hanover Geisel presented it to President-Emeritus Ernest Martin Hopkins. Mr. Hopkins is plan- ning to turn it over to the art galleries in the new Hopkins Center, but where it will hang and when is something that probably is haunting the Center’s art ad- visory board.

The Geisels’ generosity to Dartmouth goes well beyond this gift of an oil paint- ing. Two years ago in an article appear- ing in The New Yorker magazine E. J. Kahn Jr. wrote; “When he [Geisel] was asked to contribute to a building fund drive a few years ago, he replied off- handedly that he was leaving Dartmouth a little something in his will. The little something proved to be the copyrights on most of his books!”

Geisel’s going to Oxford from Dart- mouth came about in a rather ironical way. He had applied for a fellowship to study at Oxford and was so certain he would receive it that he wrote home to inform his father of the good news.

“The day I got Ted’s letter,” the elder Geisel told us, “I bumped into a friend who published the Springfield Union and told him about it. The next day the story appeared in his paper. A week later Ted wrote that the fellowship had fallen through, so I had to send him to Oxford just to keep the newspaper story ac- curate!”

It was, of course, at Oxford that Ted Geisel and Helen Palmer met. They were both taking a course in English literature and the story has it that Ted was doing sketches in his notebook instead of tak- ing notes and that Helen saw them and encouraged him to do more. Ted, who had visions of getting his graduate degree from Oxford and returning to Dartmouth as an English teacher, was reluctant to abandon the academic life, but finally he agreed to try his hand at earning a living through his art. He returned to this coun- try, sold his first cartoon, and in 1927 married Helen in New Jersey.

Finances have always been rather be- wildering to Ted, so Helen has managed the family accounts and also handles most of Dr. Seuss’ correspondence. When he turned to writing and illustrating books, in the mid 1930’5, Geisel was not certain whether he could make a full- time living in this way. As late as 1954 he asked his agent, Phylis Jackson, if he might count on $5,000 a year from royalties. She assured him he could and her prediction has turned out to be some- what on the conservative side.

Ted and Helen Geisel are an uncom- monly close and devoted couple. Their common interests, their quick under- standing, and their work together make them virtually inseparable. In recent years they have been working together on Beginner Books. This educational ven- ture grew out of a Life magazine article written in 1954 by John Hersey who complained of the general dreariness and lack of readability of children’s books and suggested that Dr. Seuss or some- one do something about it. Geisel took up the challenge, but had to wrestle with the fact that a readable book for young- sters at the kindergarten and first-grade level was limited to a vocabulary of a couple of hundred words. After a some- what protracted struggle he did succeed in writing in verse The Cat in the Hat, which was published by Houghton Mif- flin as a textbook and by Random House as a trade book. It was a success from the start and the drawing of the cat in the hat became the trademark for Be- ginner Books.

Beginner Books was established out- side of Random House by Helen and Ted Geisel and by Phyllis Cerf, wife of pub- lisher Bennett Cerf and juvenile editor for Random. Geisel was president and Helen vice president. Mrs. Cerf compiled a list of about 220 words which authors for Beginner Books could use, and Ted laid down the rule that there must be one and only one illustration for each page and that the text of a Beginner Book may describe nothing that is not pictured.

“It is not easy to write Beginner Books,” Geisel told us, “and we have trouble finding people who can write and illustrate them to the satisfaction of the editors (Helen and Ted Geisel and Phyl- lis Cerf).”

Despite these difficulties, a number of such volumes were published and the small “Cat in the Hat” company grew rapidly so rapidly, in fact, that Ran- dom House finally bought them out by swapping a goodly number of shares of Random House stock for Beginner Books stock.

Plans are now afoot to expand the Be- ginner Book series into higher grades, presumably with an ever-increasing vo- cabulary. After leaving Hanover last June the Geisels spent a week with the Cerfs in New York to discuss this prob- lem.

“I hope we will expand,” Geisel ad- mitted. “We have been encouraged to do so by our consulting board of about one hundred teachers and educators around the country, who read each Beginner Book before publication and make sug- gestions. Also, the Beginner Books have been well received, not only here but in Canada and Great Britain.”

We accused Geisel of still being a frustrated teacher, pointing out that in most of his books there is a built-in moral and in some, like The Sneetches andOther Stories, a delightful allegorical touch.

Publisher Cerf had commented on this trend when we talked with him. “Ted’s books have become a little more worldly in recent years, I think, but this is good. Perhaps it reflects his experiences on Be- ginner Books.”

Cerf had gone to his shelves to try and find a copy of The Sneetches, but it wasn’t there. As a matter of fact none of the Dr. Seuss books was anywhere in the floor-to-ceiling bookcase that lines one side of the publisher’s large office.

“Somebody is always rushing in to borrow the Dr. Seuss books,” complained Cerf, “and somehow they never get back on my shelf. I don’t seem to have that problem with the other Random House books!”

But .Geisel himself doesn’t quite agree that there has been a new trend in his more recent books. “Adults and children build their own moral into my books,” he said. “You can’t really preach to young- sters, but in any creative writing you are trying to communicate some ideas. My latest book, Dr. Seuss’ Sleep Book, is more like my earlier works.”

It was inevitable that a man of Geisel’s abilities should have a try at Hollywood and Ted’s fling with what he calls “a world of fantasy” came during and im- mediately after World War 11. During the war he was associated with director Frank Capra’s Educational Film Unit and as a lieutenant colonel he helped in the production of many training and in- doctrination films for the services. After the war he and Helen collaborated on the screenplay Design for Death, which de- scribed the rise and rule of the warlords in Japan and which won a 1947 Oscar from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as the best feature- length documentary. His most famous work was the Gerald Mcßoing-Boing series, featuring the antics of a gong- faced boy who conversed only in a series of sounds. This won an Academy Award for the best animated cartoon.

Geisel also wrote the scenario and de- signed the sets and costumes for a full- length Hollywood film featuring live ac- tors The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T the story of a determined piano teacher and his students. At one point in the produc- tion there were someone hundred piano- playing youngsters on set banging away. What with differences with directors and producer, the film never really came off and to this day Geisel has not seen the final version, although it was released.

Unlike his rather unhappy experiences with Hollywood, the relations between the Geisels and Random House have always been harmonious and what Ben- nett Cerf terms “publishing at its best.” The Geisels and Cerfs are the closest personal friends with the Cerfs visiting the Geisels frequently on the coast and vice-versa.

Each Dr. Seuss book is personally de- livered to Random House by its author, and Jean Ennis, the publicity gal for Random House, reports that there is a “happy gathering and great excitement as the Random House staff assemble in Mr. Cerf’s office for a reading of the latest Dr. Seuss creation.”

Dr. Seuss’ books, of course, top the Random House list and probably are the best-selling books of any publishing house. The Seuss books invariably appear high on all ratings of children’s books and have been enthusiastically endorsed by most juvenile experts. Rudolph Flesch, the learned authority on both reading and writing, predicts that the Seuss books will be read a hundred years from now. Most authorities in the field agree that Ted Geisel has proved to be one of the foremost writers for youngsters of all ages in nearly a century.

It was entirely appropriate that in June of 1955 Dartmouth College made Ted Geisel’s title of Doctor authentic by con- ferring on him an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters. President Dickey’s citation read;

“Creator and fancier of fanciful beasts . . . as author and artist you have single- handedly stood as St. George between a generation of exhausted parents and the demon dragon of unexhausted children on a rainy day. There was an inimitable wriggle in your work long before you became a producer of motion pictures and animated cartoons and, as always with the best of humor, behind the fun there has been intelligence, kindness, and a feel for humankind. An Academy Award winner and holder of the Legion of Merit for war film work, you have stood these many years in the academic shadow of your learned friend Dr. Seuss; and because we are sure the time has come when the good doctor would want you to walk by his side as a full equal and because your College delights to acknowledge the distinction of a loyal son, Dartmouth confers on you her Doc- torate of Humane Letters.”

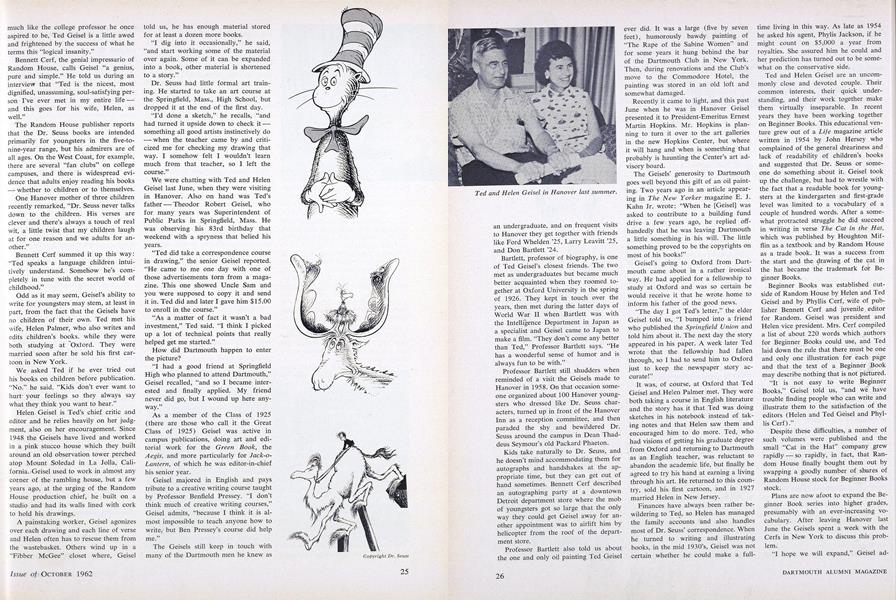

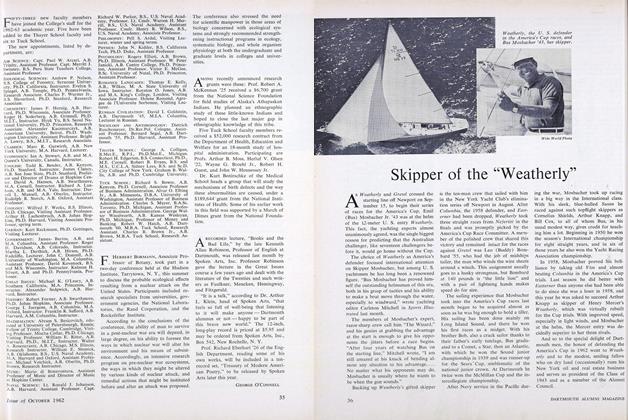

Ted and Helen Geisel in Hanover last summer.

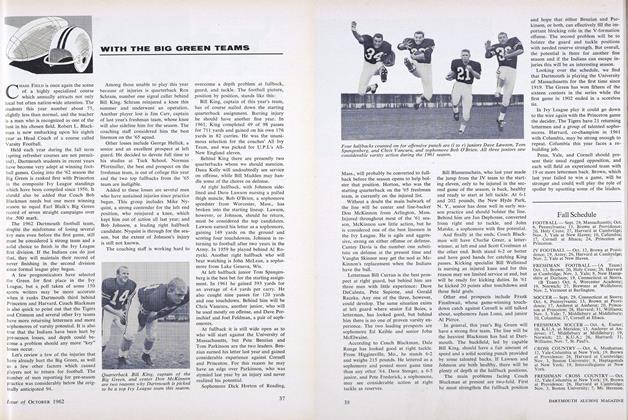

Dr. Seuss fans getting their books autographed on the campus in 1958.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Vanishing Ability To Write

October 1962 By George O’Connell -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

October 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTRUSTEES SANCTION A FOURTH TERM

October 1962 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1962 By George O’Connell -

Sports

SportsWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1962 By Dave Orr ’57 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

October 1962 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, RUSSELL J. RICE

CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45

-

Books

BooksWHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART.

April 1954 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

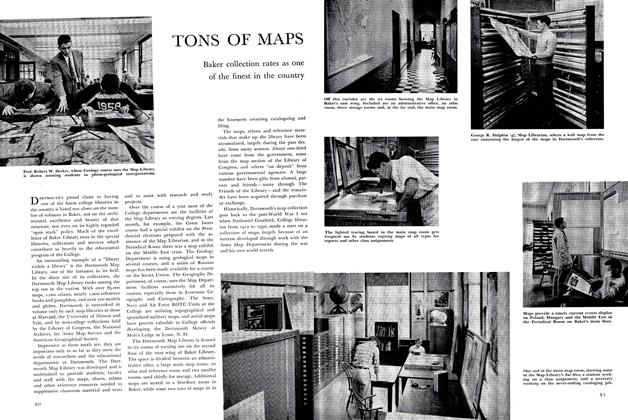

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

Feature30,000 Dartmouth Men Are Her Friendsand Problems

December 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

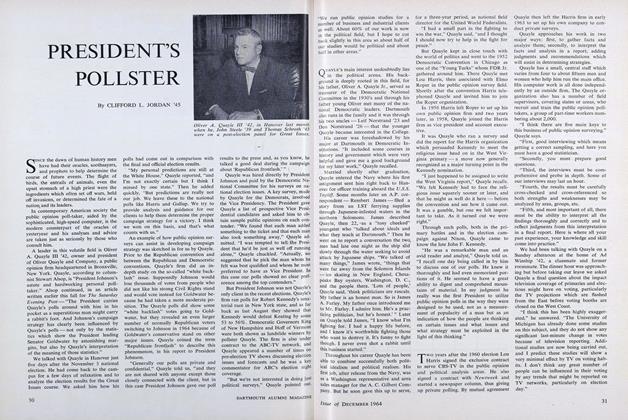

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

DECEMBER 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

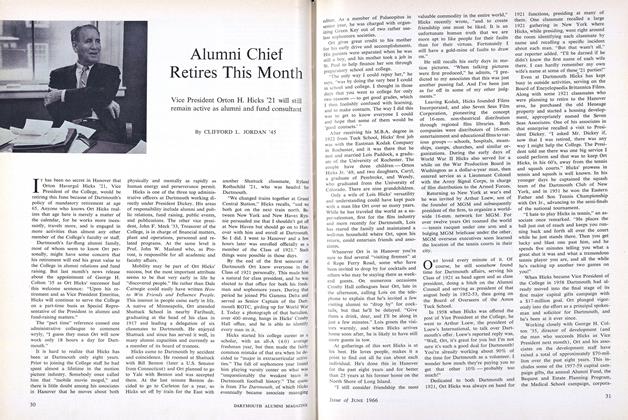

FeatureAlumni Chief Retires This Month

JUNE 1966 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Library Revolution

MAY 1968 By Clifford L. Jordan '45

Features

-

Feature

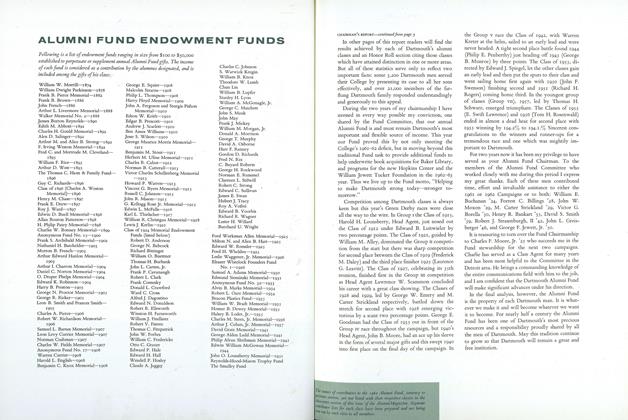

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Cover Story

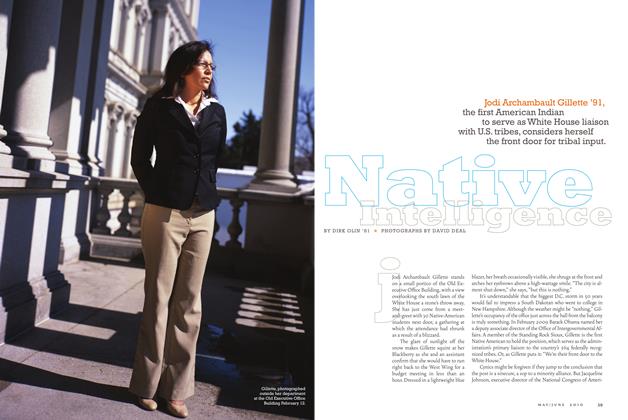

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

APRIL 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Cover Story

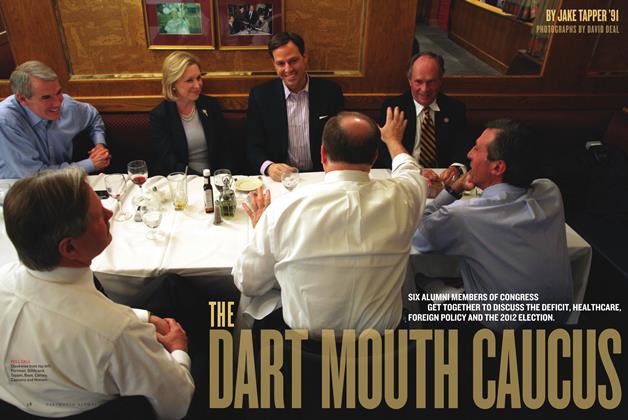

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

July/August 2011 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureAmbassadors Without Portfolio

APRIL 1965 By PAUL C. PRINGLE '65 -

Feature

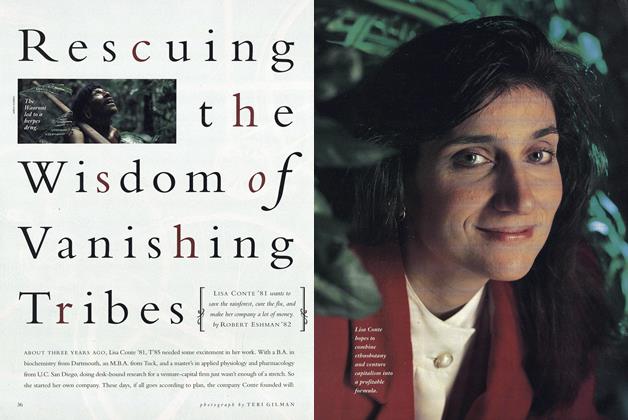

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82