Jeffrey Hart, the popular, eccentric-dressing English prof, isretiring. Jeffrey Hart, the take-no-prisoners conservative columnist, is not.

AFTER MORE THAN 30 YEARS of teaching, English Professor Jeffrey Hart approached the lectern on a crisp Friday afternoon last spring and delivered his final lecture on the Age of Johnson. Fifty or so students took up seats in Dartmouth Hall that day, but they would not hear much about either Samuel Johnson or his Age. Instead, Hart's closing talk was long in another one of his favorite subjects: the decline of higher education, especially the kind practiced at Dartmouth.

"The fact of the matter—and it would be well to put it squarely—is that the vast majority of Dartmouth seniors are profoundly uneducated—sunk, as Alexander Pope would have put it, in the Serbian Bog of ignorance," said Hart.

His students shifted a little uncomfortably in their seats. A few laughed, some appreciatively, others a little nervously. Some beat a path for the exits, and more would follow as Hart continued.

"Students come to the College ignorant, and they leave it ignorant," Hart read. "Quite possibly, a couple dozen seniors leave Dartmouth with the rudiments of a serious education. The College itself, in its official posture that anything is as good as another, that push-pin is as good as Pushkin, has not helped them. Except for a few seniors, the rest go forth, zombie-walking through the hallways of the mind."

A few students doubtlessly had heard this before. Hart had already published much of it in this magazine and a section of it appeared in The National Review a decade ago. And it clearly was not news they wanted to hear. But Hart read on for nearly an hour, sipping from a Coke and ignoring the growing number of empty seats in front of him.

By the end of this school year, Hart will be officially retired. He will pack up his pictures of Presidents and Pinochet and clear out his Sanborn office, and Dartmouth College's most controversial professor will be gone.

It is probably safe to say that he will not be widely missed among the faculty and administration. Hart's colleagues in the English Department say he has not played an important role in departmental issues for years. Few can remember the last time he attended a faculty meeting, and Hart says that on the rare occasions that he does so, he is too disgusted to speak up. President James O. Freedman won't even return a phone call on the subject of Jeffrey Hart, much less offer thoughts on his parting.

And yet, when Hart leaves, Dartmouth will lose a rare commodity: a street fighter in a raccoon coat. Hart has spent his entire career—several careers, really—mixing it up. He is candid, personally charming but perfectly willing to make enemies if that's what it takes to advance his agenda. And his agenda, as anyone who knows Dartmouth knows well, is relentlessly, sometimes wittily, other times viciously or carelessly, conservative. Here is Hart, in his own words:

On AIDS: "The fact of the matter is that AIDS is a culturally honored disease and the message being delivered is that the homosexual practices that transmit the disease are just A-Okay."

" On the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which opposed the Supreme Court nomination of Clarence Thomas: "The NAACP does not think black Americans should be intellectually independent. It

thinks they should labor on the liberal plantation."

On feminism: "The feminist Bowdlerists are the new Stalinists in the academy. They certainly believe that there are commanding grudges, which are more important than truth, fairness, intelligence and good writing."

On affirmative action: "The contemporary diversity movement means precisely the opposite. It means racial and cultural apartheid."

On Dartmouth: "The students are fine, the faculty is OK, and the administration stinks."

IT IS ONLY FAIR THAT I ADMIT to some basic differences of opinion with Hart. I was a reporter and later the publisher of The Dartmouth, while Hart's minions manned the word processors at our arch-rival, The Dartmouth Review. Hart wants to revive the old Indian symbol; I find the symbol puerile and demeaning, and—with classmate Alison Frankel—published a bumper sticker with the slogan, "Wah Who Cares?" He is a bonemarrow conservative; I wrote a weekly column for The D aptly entitled, "Out in Left Field."

But until I spent a week with him for this article, I had never met Hart. I knew him the way most people do—through his column, a nationally syndicated, twice-weekly harangue about whatever happens to be on Hart's mind. And I knew him through his campus reputation, as an engaging teacher who also happened to be one of the easiest graders around.

The Hart of national-syndication fame is cold and mean-spirited. But Hart in person is approachable and amiable. He laughs easily. He relishes good gossip, and tells tales about his friends as well as his enemies.

He is generous with his time, and, at a campus given to self-importance, refreshingly direct. He answers questions without flinching, whether they are about Dan Quayle (he unsurprisingly considers the Vice President "smarter than people give him credit for") or the widespread rumors of Hart's excessive alcohol consumption ("I drink a couple of cocktails in the evening, but some of these reports are absolute fabrications," he says, nursing a cocktail).

And through it all, the Brooklyn-born boy who grew up in Long Island and has spent his adult life with one foot in Hanover and another in New York and Washington is joyfully engagingly theatrical. He strides jauntily across the Green, decked out in bright blazers and nifty hats. I interviewed him half a dozen times over five days, and on each occasion he wore a different political pin. Not one of them was for a candidate more current than Eisenhower.

He is a character, and the same campus that will breathe a sigh of relief when he retires may also feel a pang of regret. For in Hanover, there is nobody quite like Jeffrey Hart.

BORN BETWEEN THE WARS, Hart was the only child of Clifford and Gladys Hart. It was common in those days for families to have just one childtimes were hard, and though Hart's family was not especially poor, any more children would have posed a hardship.

Hart's father, a member of Dartmouth's class of '21, was an architect, and his mother, a former Broadway actress, was an expert typist of architectural documents. There was little new construction during the Depression, and that made architecture work hard to come by. Hart's mother worked where she could, and his father earned money teaching high school and night school.

By 1940, however, business rebounded, and from then on Jeffrey Hart grew up in polo shirts and loafers. He was never again a child of want, and he was never, ever a liberal.

"He's been a conservative since he came out of the egg," says English Professor Bill Spengemann, a friend of Hart's. "That makes him an entirely different kind of animal."

Hart attended Stuyvesant High School in New York, and then followed in his father's collegiate footsteps, arriving in Hanover in the fall of 1947, just as World War II ended and just in time for the 1950s, Hart's favorite decade and the subject of one of his many well-received books. Hart studied in Hanover for two years, but left and finished his undergraduate degree at Columbia. After completing his master's, he then returned to Columbia for his doctorate and stayed on to accept a post as an assistant professor.

It WAS 1961. John F. Kennedy was in the White House, the civil rights movement was gathering steam, and a 31-year-old professor named Jeffrey Hart—by then married and a father of the first of his four children—was hunkering down for a decade in which he would hold the fort against every new idea the Left could offer up.

Throughout the 1960s, Hart published often and often brilliantly Some of his work was overtly political, but most was devoted to literature. He served as editor of the Burke Newsletter, and published books, book reviews, and scholarly articles. He became a full professor in 1965.

In his courses, Hart navigated the periphery of the 1960s. He says that during the entire course of the Vietnam War he never mentioned Vietnam once in class. But political messages are not hard to find in his course work. Hart greatly admires the cool reason of the eighteenth century; and he sings the praises of Edmund Burke, the French Revolution's passionate British opponent. As the American scene exploded in revolutions large and small, intense and incoherent. Hart would offer his students an alternative model from an age of eloquence and reason.

In 1968 he joined then-Governor Ronald Reagan as a speechwriter and consultant for several months, then jumped to Richard M. Nixon's camp for the general election and transition to the White House. Hart quickly realized that politics as practiced in Washington was not for him.

"The arrogance is astounding," Hart remembers. "You have these junior aides, all walking fast to get to the next meeting as if the world depended on it."

So Hart returned to Hanover, where he has spent the past quarter-century strolling the campus at his own pace. He was divorced in 1979 and remarried in 1981. In the years since Hart did his stint with Reagan and Nixon, Presidents and presidential aides have come and gone. Hart has remained, tending the conservative fire.

HART'S NATIONAL REPUTATION comes from three sources. He is an author of books, a senior editor of The National Review, and a nationally syndicated columnist. His work for the Review, much of it in the form of thoughtful essays and book reviews, is studied and careful, some of it even ideologically moderate. His books range from light histories of the forties and fifties to serious, reflective collections of essays on literature and the academy.

Among some of Hart's peers, there is a sense that his most impressive days as a scholar are behind him. His recent writings tend toward social essays and commentary, veering away from some of the more rigorous scholarly work that earned him a national reputation as a brilliant young professor early in his career. Yet that criticism must be couched in terms of his overall writing. Some of Hart's recent work remains impressive, even it it takes a different tack. His latest book, Actsof Recovery, is a self-described collection of "essays on culture and politics," and it features some of Hart's sharpest writing. It is engaging, ascerbic, and often thought-provoking. It is, as fellow conservative George Will described it, a "model of high journalism."

His column, for which he is best known, displays a different side of Hart. He says he vowed years ago never to take longer than an hour to write one. It shows.

He rarely breaks news or challenges the readers with new concepts. He is, most often, merely just one more curmudgeonly voice dressed up as a sort foreign correspondent, reporting back to civilization from an outback populated by pretentious and overbearing liberals.

The column gives Hart an avenue to take his enemies to task, and he can sling a phrase. When political commentator Morton Kondracke '60 had the temerity to take on The Dartmouth Review, Hart wasted little time striking back. "I knew that he is much less impressive intellectually than he deems himself, but that is a common enough affliction," Hart wrote. "I thought, however, that he was an honest man. I was wrong." Hart has never been dull. Lately, however, his column has attracted attention of a different sort.

In September 1991, Hart was eating lunch at a hotel in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and while there chanced to take in a breathtaking event. "All of a sudden I saw thousands of blue dancing lights heading downstream,"

Hart wrote. "It was an amazing sight. The blue fish possessed a sort of cosmic vitality. The very energy of these newly born fish, the sun glinting on their blue backs as they leaped and swam, was a joyful spectacle."

Then, as Hart and fellow diners watched in horror, the fish were scooped up and "dumped like garbage on the banks of the river." It was, a breathless Hart reported in his column, a fish kill, a "cowardly spectacle."

Turns out, though, that it wasn't. In fact, the "newly born fish" that possessed such "cosmic vitality" actually were rubber blue whales, part of a promotional gimmick sponsored by a local museum. The fish kill was, in fact, a fundraiser. The people of Grand Rapids did not take kindly to Hart's work. Local papers, radio stations, even the mayor thoroughly mocked him.

So Hart wrote another column. And if the first is a study in what a journalist is never supposed to do, the second is a model of what can happen if you pick a fight with someone who buys ink by the barrel. Rather than apologize for the original mistake, Hart went on the offense, tongue in cheek, to be sure, but with the vigor of a man far more used to chastising others than admitting his own mistakes.

"The use of rubber whales sends exactly the wrong message to the citizens of Grand Rapids....Perhaps that is why Grand Rapids officialdom reacted so defensively to my original column. Perhaps they realize the symbolism is all wrong. Or perhaps they sense obscurely that the event itself is looney."

Hart's conclusion: "Grow up, Grand Rapids."

IF IT'S ANY COMFORT to the people of Grand Rapids, they're in good company. Almost anyone who has publicly criticized The Dartmouth Review—and that makes for a pretty big group—has felt Hart's lash. In fact, although Hart disclaims any official relationship to the Review, he has always served as its godfather and unofficial apologist. That's pretty near a full-time job, and since Hart's style of defense is to attack the attacker, he has had his share of fights on behalf of the paper. When James Freedman, for instance, accused the Review of racism—an opinion that Hart does not share but which editors of the Review have exposed themselves to by printing distinguished works such as "Dis Sho' Ain't No Jive, Bro'" Hart ran the president through the gauntlet. Calling Freedman a "silly narcissist," Hart concluded: "I believe that I have encountered only three people in my experience whom I would consider evil, and I do not use that word lightly. By evil I mean cold, arrogant, cynical, egotistical, and brutal. Those three are Gore Vidal, Roy Cohn, and Dartmouth's James Freedman."

Yet, for a man who worked for Nixon and publicly compares a college president with Roy Cohn, Hart is remarkably thin-skinned about criticism of himself. He has threatened to sue at least one campus publication, and woe to the journalist who crosses his path, even when that journalist is a former ally.

Take Greg Fossedal '81, who founded The Dartmouth Review along with several others, including Hart's oldest son, Ben Hart '81. In 1987 Fossedal, a columnist and fringe politico, took it upon himself to lecture The National Review on its failings and offer suggestions for its future. Suggestion Number One, Fossedal wrote: "Send away some of the senior editors on alternating sabbaticals. Jeff Hart, Joe Sobran, Tom Bethell, and Richard Brookhiser need to be forced to publish first-rate books, do some serious writing for publications, and just plain think."

Now, the closest Fossedal has ever gotten to a "first-rate book" is Baker Library, so it's no surprise that Hart was offended by this suggestion from an impudent and unproven idealogue. But even Fossedal must have been surprised by the anger he stirred up.

Less than a month after Fossedal's column appeared, Hart wrote to George Champion '30, former chairman of Chase Manhattan and a deeppocketed, nationally influential conservative. Hart termed Fossedal's criticism

"excommunicative in nature" and told Champion that he would submit his "speedy resignation" from the board of the Hopkins Institute unless Fossedal was removed from that organization. "Gregory Fossedal, whom I counseled and advised for many years, has personal problems," Hart wrote. "He is evidently convinced that he disposes of personal talents of a prophetic and charismatic character, which illusions are in the nature of fantasy and no doubt account for his failure to establish deep roots in any of the enterprises in which he has associated."

Whether Champion got Hart's message is unclear. That Fossedal did is undeniable. Shortly after Hart sent his letter, Fossedal wrote another column. This time he heaped praise on Hart for his noble fight against political correctness on campus.

AMONG HIS PEERS, Hart rarely displays the temper that brought Fossedal to his knees. English Department Chairman Lou Renza calls Hart "a marginal figure when it comes to departmental matters" and criticizes his attacks on Freedman as "egregiously personal." However, Renza adds: "People think of him as some cruel ogre, but that's not the case."

Hart enjoys tennis, and plays with colleagues of all political persuasions. He enjoys a good argument. Just about the only people he cannot abide are feminists—which seems fair enough, since they cannot stand him either. But many of his fellow professors seem frankly scared to talk to him, or even to talk about him. As a result, Hart seems to have become increasingly isolated at Dartmouth.

Some of Hart's friends attribute that isolation to his political views hard-edged conservatism in a faculty that favors mushy, elitist liberalism. Others write it off to what Bill Spengemann calls "seventh-grade social etiquette," colleagues avoiding Hart in public because they don't like to be seen with an unpopular guy.

If Hart's reputation with his colleagues is sometimes strained, however, it is secure with his students. For at least a decade, Hart's course on Johnson has been among the most popular offerings at Dartmouth, in part because it's considered one of the easiest A's on campus. In my day, everyone knew Hart simply as "Easy Jeff." Hart denies his reputation, but legends live on. According to the most widely repeated of those legends, a student in Hart's Samuel Johnson course one year, turned in a paper on Ben Jonson. The paper, legend has it, came back with a B-plus, accompanied by a single comment: "Great paper, wrong Johnson."

"Not true," says Hart. "That's just a prima facie impossibility. I grade tougher than the College average."

In class, Hart speaks well and with touches of enthusiasm. Yet even there, the contradictions of Jeffrey Hart are not hard to spot. He teaches a period that he seems to love so much that he does not encourage students to challenge or question it. Instead he asks them to join him in appreciating it, an approach he would be the first to attack if practiced by a leftist teaching Marx.

More tellingly, even as Hart lavishes praise on the great professors, he seems not to emulate them. In his final lecture, Hart paid tribute to Columbia's Mark Van Doren, who, Hart said, was "in the opinion of many...the best classroom teacher they had ever encountered."

"His lectures were conversations," Hart said, "launched casually with some observations, and then he would draw a student in the class into the conversation. He had a way of creating intelligence in whatever student he picked through these exchanges."

Hart read those words to his students verbatim, quoting his own, already-published work. He drew no student into conversation, and he took no questions. He read, he finished, and he left for a panel discussion in New York, seemingly oblivious to the contradiction between the professor he described and the professor he is. (Hart notes that he was speaking to a class of 230, while Van Doren had a class of 30.)

This time next year, he will be a professor no more. There are books to write, National Review editorial meetings to attend, seminars to conduct. And, of course, there still will be the column. In fact, Hart's retirement from Dartmouth may actually mean that people outside of Hanover hear more of him, not less. And for those at the College who might have looked forward to a little peace and quiet, that's hardly comforting. "The Jeffrey Hart of Dartmouth really is not influential at all," says Tom Luxon, an English professor and occasional foe of Hart's. "The Jeffrey Hart that's had an impact on the College and the country is the syndicated columnist. And that Jeffrey Hart is not retiring."

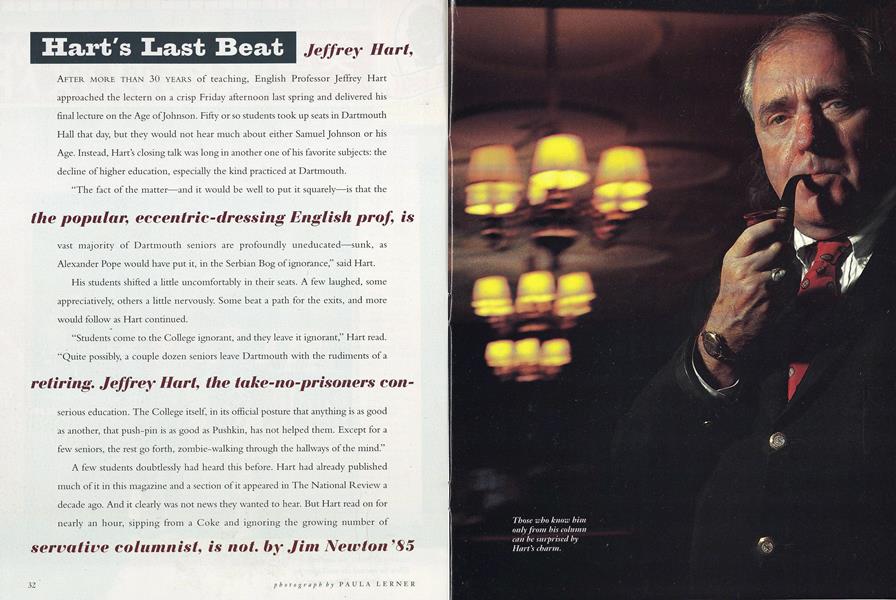

Those who know himonly from his columncan be surprised byHart's charm.

Hurt helped Nixonwithhis speechesbut grewtiredjunior aides.

His first ventureinto public life wasas a speechwriterand consultant forGovernor Reagan.

This photoof a Pinochetinterview joinsEd Koch andLionel Trillingon his wall.

Tennis washis sport hereand in N.Y.

JIM NEWTON is a reporter for TheLos Angeles Times, where he covers federal agencies.

He will not be widely missed among faculty andadministrators. And yet, Dartmouth will lose arare commodity: a street fighter in a raccoon coat.

As the American scene exploded in revolutionslarge and small, intense and incoherent Hartwould offer his students an alternative model.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

November 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

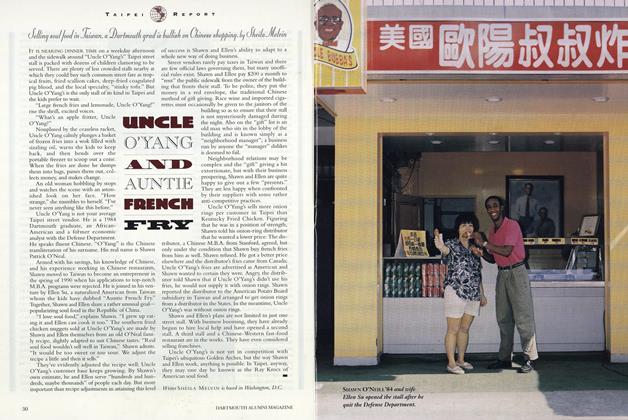

FeatureTaipei Report

November 1992 -

Article

ArticleIs Socialism Really Dead?

November 1992 By William L. Baldwin -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1992 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

November 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

November 1992 By Mark Stern

Features

-

Feature

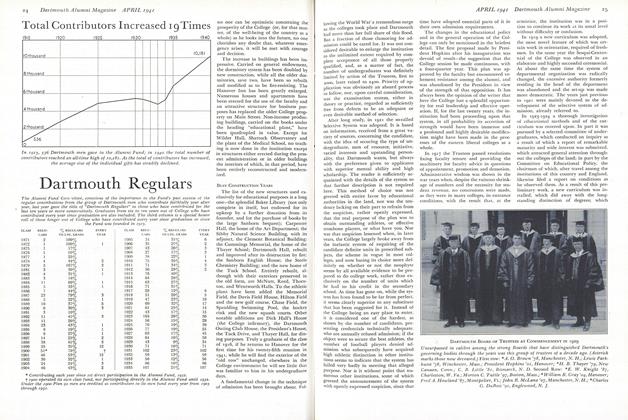

FeatureDartmouth Regulars

April 1941 -

Feature

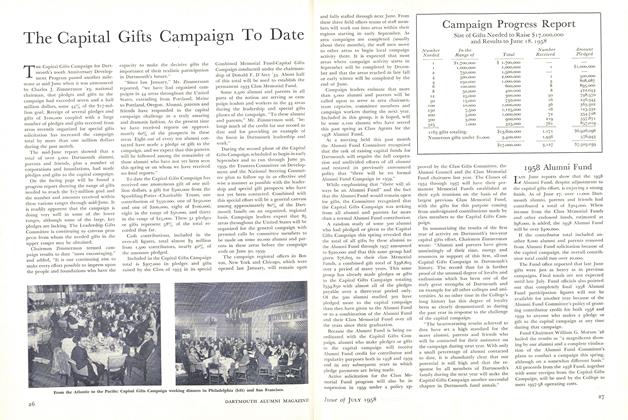

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

FEBRUARY 1959 -

Feature

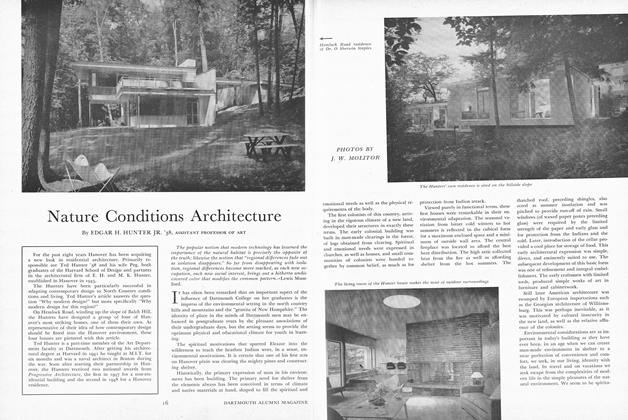

FeatureNature Conditions Architecture

June 1954 By EDGAR H. HUNTER JR. '38 -

Feature

Feature"The Individual and the College"

October 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May/June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77