Two-year national study, directed by Prof. Kitzhaber, finds college standards low and calls for reforms

The ability to write clear, concise, and reasonably correct English prose is usually considered one of the marks of an educated man. Yet evidence abounds that many individuals with degrees and even strings of degrees cannot express themselves on paper. Part of the reason may be the increasing complexity and specialization of knowledge that leads to intramural jargon. An- other part must lie in Rousseau’s contention that “whatever gifts a man may be born with, he cannot learn the art of writing in a moment.”

But is the weakness in the educational system? Why can’t otherwise intelligent men “communciate” and what can be done about it?

In the businesses and professions, word-weary executives point to the col- leges and universities. College professors of upper-level courses ask the English Department querulously, “Can’t you teach them to write a simple declarative sentence with the proper grammar, spell- ing, and punctuation?” The English De- partment, responsible in most colleges for composition courses, points to the sec- ondary school where in its view the fundamentals of grammar, punctuation, and spelling should be taught.

Now comes the Kitzhaber Report which tells us that soon the finger of scorn may be pointed in the other direc- tion. The secondary schools are doing a better job; the Freshman Composition instructors are being forced to improve their offerings; and the chief onus is shifting to the late college years, the graduate schools, the professions and business which are not demanding good writing.

Two years ago Dartmouth undertook a study of English composition courses with the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Albert R. Kitzhaber, chairman of English composi- tion at the University of Kansas, came to Hanover to head the study. It was cen- tered at Dartmouth but was nationwide in scope.

Professor Kitzhaber completed the study and a 248-page report this summer. It had begun with an ad hoc faculty committee on student writing. The mem- bers knew that Dartmouth attracts stu- dents of superior intelligence but that a good many of them are handicapped be- cause they can’t write correctly or pre- cisely. They need training in the princi- ples and practice of written discourse and Dartmouth has required such train- ing. The committee was convinced that after this instruction most students do write better, but, they asked, was the improvement worth the time and effort involved? Could composition be taught more effectively?

A second question, equally important, was: Can anything be done to ensure that students will continue to write at least as well after they have left fresh- man English as they do while taking it? The committee’s impression was that once English Composition is completed many students fall back into their old habits and write as carelessly as before. The faculty at large seemed to feel that good student writing is the particular province of the English Department, that Freshman English should fix the habits of correct usage and clear, orderly writ- ing forever. Another way of putting this question was: What is the general fac- ulty’s responsibility toward good student writing and could its members be per- suaded to accept the responsibility more fully?

Professor Kitzhaber studied the com- position-course offerings of 94 col- leges and universities. He made detailed analyses of Dartmouth students’ papers, from freshman through senior years. He traveled throughout the country and dis- cussed the subject with English-faculty members.

His survey of the nation revealed that freshman composition courses are sub- collegiate in intellectual content and are considered step-children in college cur- riculums. Their weaknesses include con- fusion in purpose, content, and organiza- tion, compounded by bad teaching and poor textbooks. In many colleges stu- dents are still diagramming sentences and writing essays on “My Favorite Teacher” or “A Happy Vacation.”

Teaching composition is a low-prestige job academically, the purgatory through which graduate students and very junior instructors advance to the teaching of the literature they have specialized in. Many have little or no training in language, rhetoric or logic, and even less interest in them.

Textbooks are usually “cut-and-paste” anthologies, the choice of which seems dictated by “local authorship.” Two- thirds of the 57 books used on the 94 campuses were used only on a single campus (by coincidence, perhaps, usu- ally the one on which the author taught).

This sorry situation needs remedying simply because it needs remedying, Pro- fessor Kitzhaber indicates, but if it is not done soon the colleges may find them- selves in the embarrassing position of having reforms pushed on them by their students.

The secondary schools were the princi- pal scapegoat in the post-Sputnik soul- searching, and they have responded. Now it’s the colleges’ turn. In the selective schools, freshman remedial English courses are on the way out. The so-called “review of fundamentals,” a traditional feature of the freshman course, is being dropped at many colleges and the writing clinics are being discontinued. In their place the top schools are offering courses in literature with a certain amount of re- quired writing based on literature, and honors courses in writing are proliferat- ing.

Up to this point the picture appears bright, but it darkens quickly. Professor Kitzhaber says that unless a majority of the facultyin other departments co- operate to maintain standards of good writing, the gains of even high-quality freshman English instruction are dimin- ished or lost. A lack of such faculty in- terest confirms the students’ suspicion “that precise and accurate English is an exasperating dialect that one uses when writing for English teachers.”

Professor Kitzhaber points out repeat- edly that correct writing is not necessarily good writing. But a high correlation exists.

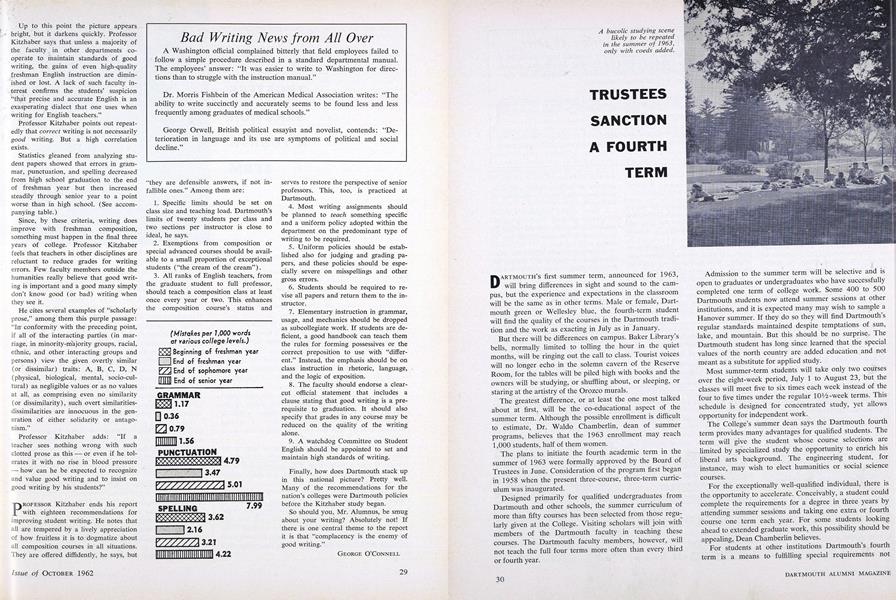

Statistics gleaned from analyzing stu- dent papers showed that errors in gram- mar, punctuation, and spelling decreased from high school graduation to the end of freshman year but then increased steadily through senior year to a point worse than in high school. (See accom- panying table.)

Since, by these criteria, writing does improve with freshman composition, something must happen in the final three years of college. Professor Kitzhaber feels that teachers in other disciplines are reluctant to reduce grades for writing errors. Few faculty members outside the humanities really believe that good writ- ing is important and a good many simply don’t know good (or bad) writing when they see it.

He cites several examples of “scholarly prose,” among them this purple passage; “In conformity with the preceding point, if all of the interacting parties (in mar- riage, in minority-majority groups, racial, ethnic, and other interacting groups and persons) view the given overtly similar (or dissimilar) traits: A, B, C, D, N (physical, biological, mental, socio-cul- tural) as negligible values or as no values at all, as comprising even no similarity (or dissimilarity), such overt similarities- dissimilarities are innocuous in the gen- eration of either solidarity or antago- nism.”

Professor Kitzhaber adds: “If a teacher sees nothing wrong with such clotted prose as this or even if he tol- erates it with no rise in blood pressure how can he be expected to recognize and value good writing and to insist on good writing by his students?”

Professor Kitzhaber ends his report with eighteen recommendations for improving student writing. He notes that all are tempered by a lively appreciation of how fruitless it is to dogmatize about all composition courses in all situations. They are offered diffidently, he says, but “they are defensible answers, if not in- fallible ones.” Among them are:

1. Specific limits should be set on class size and teaching load. Dartmouth’s limits of twenty students per class and two sections per instructor is close to ideal, he says.

2. Exemptions from composition or special advanced courses should be avail- able to a small proportion of exceptional students (“the cream of the cream”).

3. All ranks of English teachers, from the graduate student to full professor, should teach a composition class at least once every year or two. This enhances the composition course’s status and serves to restore the perspective of senior professors. This, too, is practiced at Dartmouth.

4. Most writing assignments should be planned to teach something specific and a uniform policy adopted within the department on the predominant type of writing to be required.

5. Uniform policies should be estab- lished also for judging and grading pa- pers, and these policies should be espe- cially severe on misspellings and other gross errors.

6. Students should be required to re- vise all papers and return them to the in- structor.

7. Elementary instruction in grammar, usage, and mechanics should be dropped as subcollegiate work. If students are de- ficient, a good handbook can teach them the rules for forming possessives or the correct preposition to use with “differ- ent.” Instead, the emphasis should be on class instruction in rhetoric, language, and the logic of exposition.

8. The faculty should endorse a clear- cut official statement that includes a clause stating that good writing is a pre- requisite to graduation. It should also specify that grades in any course may be reduced on the quality of the writing alone.

9. A watchdog Committee on Student English should be appointed to set and maintain high standards of writing.

Finally, how does Dartmouth stack up in this national picture? Pretty well. Many of the recommendations for the nation’s colleges were Dartmouth policies before the Kitzhaber study began.

So should you, Mr. Alumnus, be smug about your writing? Absolutely not! If there is one central theme to the report it is that “complacency is the enemy of good writing.”

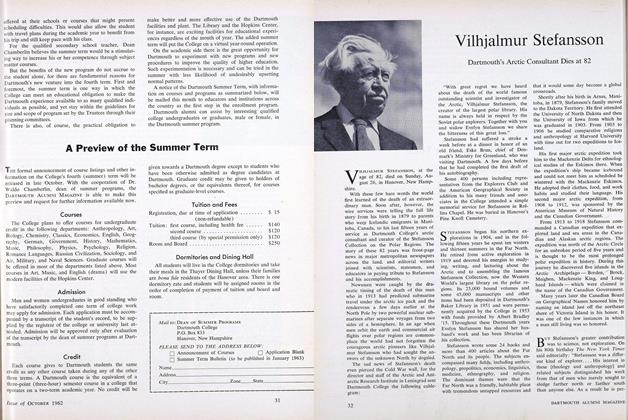

Dr. Albert R. Kitzha- ber came to Dart- mouth in 1960 as Re- search Professor of English and for two years directed the Col- lege’s study of student writing, supported by a grant from the Car- negie Corporation of New York. Professor Kitzhaber, formerly chairman of English Composition at the University of Nebraska, now heads the new “Project English” Curriculum Study Center at the University of Oregon, where a five- year project is aimed toward major revision and improvement of the curriculum in lan- guage, literature, and written and oral com- position in grades 7 through 12. The new center is one of four set up under grants from the U. S. Office of Education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

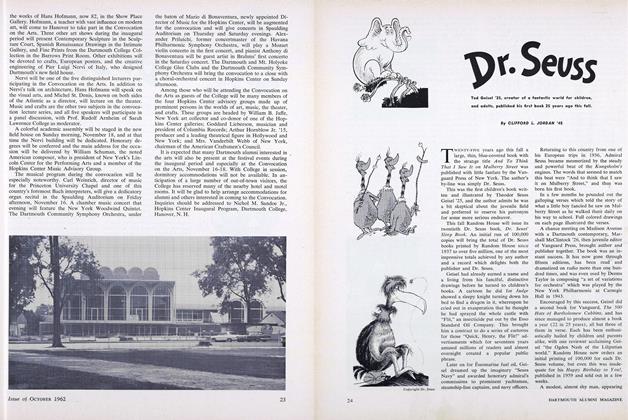

FeatureDr. Seuss

October 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

October 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTRUSTEES SANCTION A FOURTH TERM

October 1962 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1962 By George O’Connell -

Sports

SportsWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1962 By Dave Orr ’57 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

October 1962 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, RUSSELL J. RICE

George O’Connell

Features

-

Feature

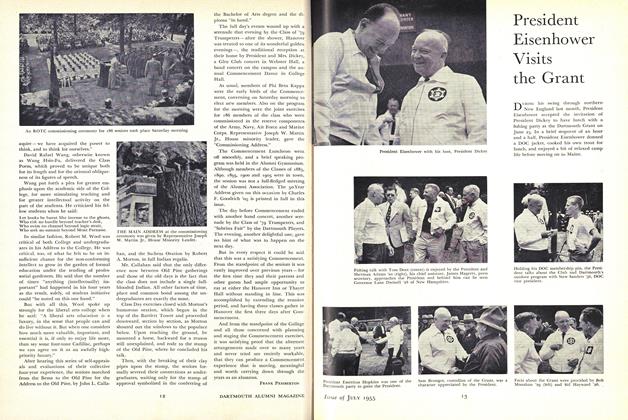

FeaturePresident Eisenhower Visits the Grant

July 1955 -

Feature

FeaturePREFACE TO DARTMOUTH

December 1954 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Mar/Apr 2012 By Jay Mead '82 -

Feature

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

OCTOBER 1996 By Robert Pack '51 -

Feature

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer