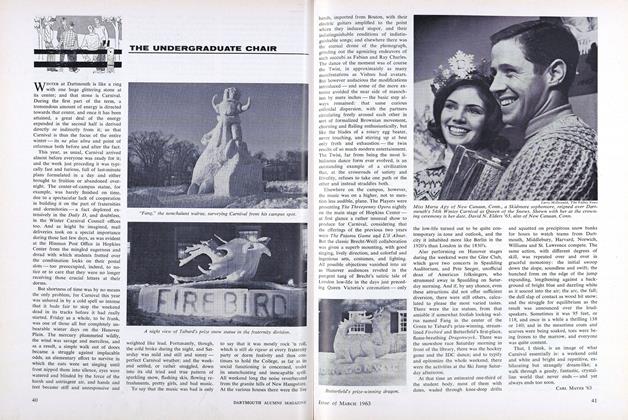

the director, Professor James Clancy, arrives, smiling amiably if perhaps a bit wearily, and a quorum being present, decides to start the first scene. At last the stage is officially populated; the actors resolve into their opening attitudes; and the initial line of dialogue resonates outwards, all the way into the lobby, where two workmen stop briefly to listen.

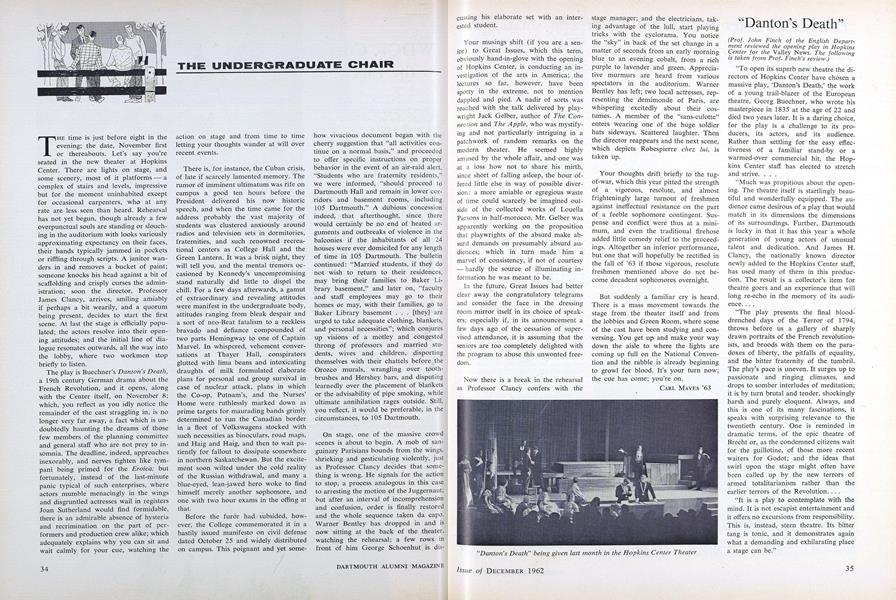

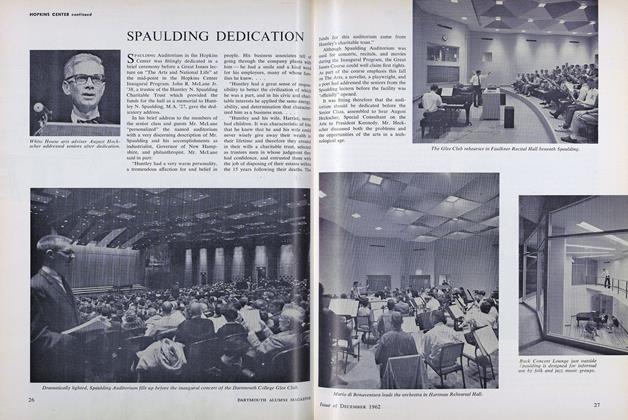

The play is Buechner's Danton's Death, a 19th century German drama about the French Revolution, and it opens, along with the Center itself, on November 8; which, you reflect as you idly notice the remainder of the cast straggling in, is no longer very far away, a fact which is undoubtedly haunting the dreams of those few members of the planning committee and general staff who are not prey to insomnia. The deadline, indeed, approaches inexorably, and nerves tighten like tympani being primed for the Eroica; but fortunately, instead of the last-minute panic typical of such enterprises, where actors mumble menacingly in the wings and disgruntled actresses wail in registers Joan Sutherland would find formidable, there is an admirable absence of hysteria and recrimination on the part of performers and production crew alike; which adequately explains why you can sit and wait calmly for your cue, watching the action on stage and from time to time letting your thoughts wander at will over recent events.

There is, for instance, the Cuban crisis, of late if scarcely lamented memory. The rumor of imminent ultimatum was rife on campus a good ten hours before the President delivered his now historic speech, and when the time came for the address probably the vast majority of students was clustered anxiously around radios and television sets in dormitories, fraternities, and such renowned recreational centers as College Hall and the Green Lantern. It was a brisk night, they will tell you, and the mental tremors occasioned by Kennedy's uncompromising stand naturally did little to dispel the chill. For a few days afterwards, a gamut of extraordinary and revealing attitudes were manifest in the undergraduate body, attitudes ranging from bleak despair and a sort of neo-Beat fatalism to a reckless bravado and defiance compounded of two parts Hemingway to one of Captain Marvel. In whispered, vehement conversations at Thayer Hall, conspirators glutted with lima beans and intoxicating draughts of milk formulated elaborate plans for personal and group survival in case of nuclear attack, plans in which the Co-op, Putnam's, and the Nurses' Home were ruthlessly marked down as prime targets for maurading bands grimly determined to fun the Canadian border in a fleet of Volkswagens stocked with such necessities as binoculars, road maps, and Haig and Haig, and then to wait patiently for fallout to dissipate somewhere in northern Saskatchewan. But the excitement soon wilted under the cold reality of the Russian withdrawal, and many a blue-eyed, lean-jawed hero woke to find himself merely another sophomore, and one with two hour exams in the offing at that.

Before the furor had subsided, however, the College commemorated it in a hastily issued manifesto on civil defense dated October 25 and widely distributed on campus. This poignant and yet some how vivacious document began with the cheery suggestion that "all activities continue on a normal basis," and proceeded to offer specific instructions on proper behavior in the event of an air-raid alert. "Students who are fraternity residents," we were informed, "should proceed to Dartmouth Hall and remain in lower corridors and basement rooms, including 105 Dartmouth." A dubious concession indeed, that afterthought, since there would certainly be no end of heated arguments and outbreaks of violence in the balconies if the inhabitants of all 24 houses were ever domiciled for any length of time in 105 Dartmouth. The bulletin continued: "Married students, if they do not wish to return to their residences, may bring their families to Baker Library basement," and later on, "faculty and staff employees may go to their homes or may, with their families, go to Baker Library basement . . . [they] are urged to take adequate clothing, blankets, and personal necessities"; which conjures up visions of a motley and congested throng of professors and married students, wives and children, disporting themselves with their chattels before the Orozco murals, wrangling over toothbrushes and Hershey bars, and disputing learnedly over the placement of blankets or the advisability of pipe smoking, while ultimate annihilation rages outside. Still, you reflect, it would be preferable, in the circumstances, to 105 Dartmouth.

On stage, one of the massive crowd scenes is about to begin. A mob of sanguinary Parisians bounds from the wings, shrieking and gesticulating violently, just as Professor Clancy decides that something is wrong. He signals for the action to stop, a process analogous in this case to arresting the motion of the Juggernaut; but after an interval of incomprehension and confusion, order is finally restored and the whole sequence taken da capo. Warner Bentley has dropped in and is now sitting at the back of the theater, watching the rehearsal; a few rows in front of him George Schoenhut is discussing his elaborate set with an interested student.

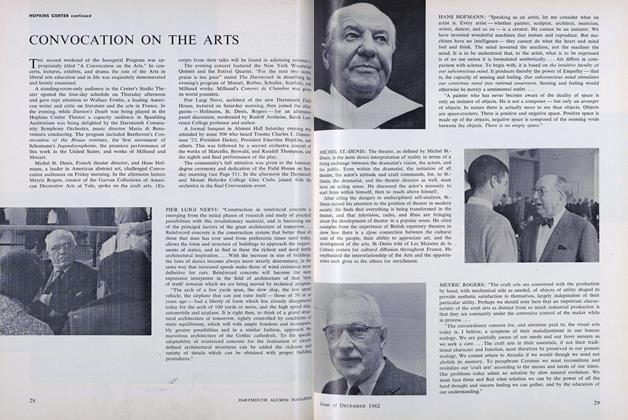

Your musings shift (if you are a senior) to Great Issues, which this term, obviously hand-in-glove with the opening of Hopkins Center, is conducting an investigation of the arts in America; the lectures so far, however, have been spotty in the extreme, not to mention dappled and pied. A nadir of sorts was reached with the talk delivered by play wright Jack Gelber, author of The Connection and The Apple, who was mystifying and not particularly intriguing in a patchwork of random remarks on the modern theater. He seemed highly amused by the whole affair, and one was .at a loss how not to share his mirth, since short of falling asleep, the hour offered little else in way of possible diversion: a more amiable or egregious waste of time could scarcely be imagined outside of the collected works of Louella Parsons in half-morocco. Mr. Gelber was apparently working on the proposition that playwrights of the absurd make absurd demands on presumably absurd audiences; which in turn made him a marvel of consistency, if not of courtesy - hardly the source of illuminating information he was meant to be. In the future, Great Issues had better clear away the congratulatory telegrams and consider the face in the dressing room mirror itself in its choice of speakers; especially if, in its announcement a few days ago of the cessation of supervised attendance, it is assuming that the seniors are too completely delighted with the program to abuse this unwonted freedom.

Now there is a break in the rehearsal as Professor Clancy confers with the stage manager; and the electricians, taking advantage of the lull, start playing tricks with the cyclorama. You notice the "sky" in back of the set change in a matter of seconds from an early morning blue to an evening cobalt, from a rich purple to lavender and green. Appreciative murmurs are heard from various spectators in the auditorium. Warner Bentley has left; two local actresses, representing the demimonde of Paris, are whispering excitedly about their costumes. A member of the "sans-culotte" enters wearing one of the huge soldier hats sideways. Scattered laughter. Then the director reappears and the next scene, which depicts Robespierre chez lui, is taken up.

Your thoughts drift briefly to the tug-of-war, which this year pitted the strength of a vigorous, resolute, and almost frighteningly large turnout of freshmen against ineffectual resistance on the part of a feeble sophomore contingent. Suspense and conflict were thus at a minimum, and even the traditional firehose added little comedy relief to the proceedings. Altogether an inferior performance, but one that will hopefully be rectified in the fall of '63 if those vigorous, resolute freshmen mentioned above do not become decadent sophomores overnight.

But suddenly a familiar cry is heard. There is a mass movement towards the stage from the theater itself and from the lobbies and Green Room, where some of the cast have been studying and conversing. You get up and make your way down the aisle to where the lights are coming up full on the National Convention and the rabble is already beginning to growl for blood. It's your turn now; the cue has come; you're on.

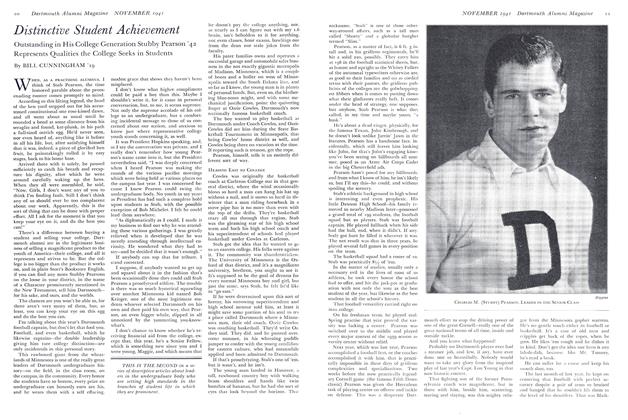

"Danton's Death" being given last month in the Hopkins Center Theater

CARL MAVES '63

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

OCTOBER 1968 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1963 By CARL MAVES '63