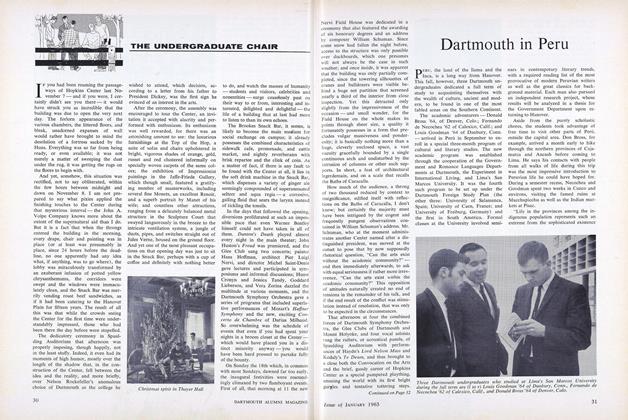

WITHOUT a doubt, winter at Dartmouth can be dreary, particularly when the day is cold, the air is sharp, the ice is slippery, and the Boston Herald is being delivered instead of the NewYork Times. You get up in the morning, cast a lackluster eye over one of the Herald's typically inept headlines or feature articles, and rush off to classes almost as a relief. The sun, as a matter of fact, is shining today; but you have the flu, and don't much notice. After classes comes lunch amid the ascetic splendors of Thayer Hall; and then, if you are like most men on campus, you amble over to Hopkins Center to collect your mail.

There were at first, and perhaps still are, sections of the student body who regarded the mail distribution area with sullen distaste, not to mention impotent ferocity. As far as they were concerned, it was all a plot conceived by a malevolent administration to lure them into Hopkins Center with nods and becks and wreathed smiles, and, when their resistance was down, to impose art on them either subliminally or directly, assaulting their senses with statues and paintings, music and mime, and generally forcing culture down their stalwart young throats. It would seem that they fully expected to be shanghaied in the lobby, injected with a paralyzing drug, and locked in a closet for 24 hours with Picasso's Guernica and the nine Beethoven symphonies, so fierce was their resentment.

But such hostility was soon outre among all but the most unreconcilable and unadulterated outdoorsmen as it became apparent that collecting one's mail at the Hinman Post Office, instead of being merely an inconvenience inaugurated by the College in an effort to save money, had certain advantages that went a long way towards compensating for its undeniable disadvantages. For one thing, mail could now be swiftly and efficiently disseminated to the undergraduate body within a fraction of the time formerly required. By noontime an entire morning's delivery could be sorted and received; no longer need the inhabitants of the dormitories languish uselessly from twelve to two every day, waiting for the habitually unpunctual mail truck to trundle by; no longer need the arrival of the post set off riots and ululations, with some students ruthlessly elbowing their way towards the boxes and snatching and clawing greedily at bundles of letters, while others, unable to assert themselves, gesture feebly from the sidelines and then discover ten minutes later that there was nothing for them anyway.

In addition to making the delivery of mail faster and more decorous, the Hinman Post Office also allows students to ignore letters easily and completely for days and even weeks on end simply by failing to check regularly on the contents of their postal slots. What better way to go socially incommunicado, to conserve one's free time by neglecting to inform oneself of meetings and engagements and dates and deadlines, to forget when it is bothersome to remember, to forestall creditors by never receiving their bills, importunate acquaintances by never reading their communications, and bad news by never hearing about it? The economic benefits of the HPO are certainly great, but its spiritual and psychological effects may turn out to be greater still.

As you trudge back to the dorm, clutchk ing mail in a hot gloved hand, you pass a strangely familiar character who nods briefly and reassuringly and is gone before you can reply in kind. Who can he be? As it turns out, it is your Dormitory Chairman. Remember him? - for in the depths of winter and mid-term exams, it is only too easy to forget the IDC man's existence. It is true that, at the moment, his official function consists on the whole of berating his charges for mopping the hallways with broken light bulbs and setting fire to their roommates; yet it is fair to say that during one part of the year at least, he is singly and collectively a figure of crucial importance and influence.

We are speaking, naturally, of Freshman Week. Since the IDC assumed the responsibility about four years ago, freshman orientation has been implemented with more finesse and intelligence than ever before. Formerly, the annual acclimatization was handled, with varying degrees of incompetence, by sundry other campus organizations, among the more bizarre of which were the Vigilantes, who favored extensive hazing as most effective means of initiating peagreens into the life of the College. This traditional Reign of Terror, however, was summarily abandoned when the IDC began to revise and enlarge the schedule of activities for Freshman Week, and now the whole affair is as devoid of brutality as it is efficient in operation.

Last fall, for instance, 144 IDC men sacrificed - how readily, it would be hard to say - the last seven or so days of their summer vacations to assemble in Hanover before registration and batten the class of '66 on the grazing grounds of Dartmouth. Their duties were indeed pastoral on an homiletic as well as gregarious level, for they were briefed almost daily by eminences of the College on topics, such as Hopkins Center and the Honor Code, that they later discussed in the dormitories with groups of freshmen individually assigned them. In addition, the agenda featured special lectures - e.g., Professor Emeritus Childs' classic dissertation on Dartmouth history - movies, picnics with faculty advisers, rallies, and other decompression-chamber specialities; so that when the '66s finally surfaced, they were as stable and serene and well-adjusted as any upperclassman could expect of an inferior race.

After this intensive exercise in artificial aging, the IDC tapers off the strong stuff for the remainder of the academic year and concerns itself merely with organizing bonfires, arranging House Parties and Carnival dances for the freshmen, collating Activities Night, and, of course, with reviewing and ruling on dormitory manners and mayhem - for example, incidents in which a student mops the hallway with broken light bulbs or sets fire to his roommate. Each dorm chairman, along with his committee, is expected to observe and to an extent enforce the rules of the College in his particular domain, and also to maintain minimum standards of civilized conduct among its inhabitants; which may explain why most IDC men have a slightly jaded air about them, as indicated by those glimmers of disenchantment in their haunted eyes. Then again, it could be that all of them are just near-sighted.

You shiver and continue your journey, carefully stepping around large masses of water, and at the same time brushing the snow from your eyes. For the winter weather this year has been nothing less than capricious; a thick snowfall might blanch the College overnight, only to be vitiated the very next morning by a tepid thaw that sent avalanches thundering from the rooftops on the Row and turned the sidewalks around the Green into canals. A few days of sun might follow: birds would be heard chirping ecstatically, the air would be balmy; watching dogs frisk in the drifts while wading through slush on the way to classes, you could almost believe that spring was lurking somewhere behind Parkhurst, waiting to be officially recognized by the administration. But no; for coming out of Thayer of an evening, you would notice the night swarming with small white flakes that frosted the dirty puddles and gleamed in the lamplight, and the cycle would start all over again, da capo, senza ritardando.

But this constant alternation of snow and schlump, you reflect, is more exciting than frustrating, since not only does it keep the skiers happy, but it places any student in the least responsive to environment on a constant alert; for instead of burying him in the boredom so indigenous to to the winter term, it stimulates him to excesses of anticipation and despair, either of them a preferable reaction. Besides, as Shelley so sweetly phrased it, "If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?" - or, translated into contemporary prose: since the newspaper strike seems ended, won't the New YorkTimes soon resume publication? What a thought to warm a cold March day!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

April 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureAUTOMATION: Progress vs. Problem

April 1963 By CLYDE E. DANKERT. -

Feature

FeatureSummer Term Close to Count-Down

April 1963 By R.J.B. -

Feature

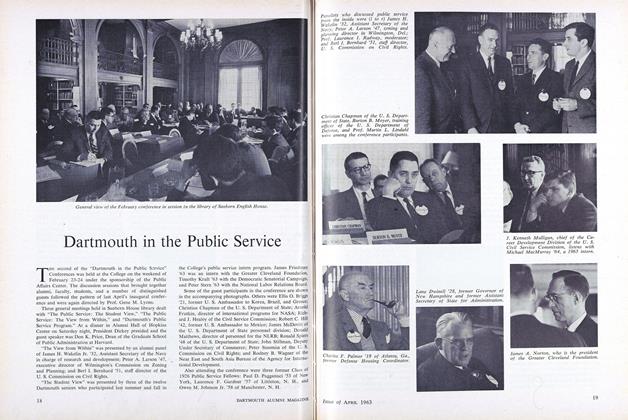

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

April 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

April 1963 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1963 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, THOMAS B.R. BRYANT

CARL MAVES '63

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1963 By CARL MAVES '63