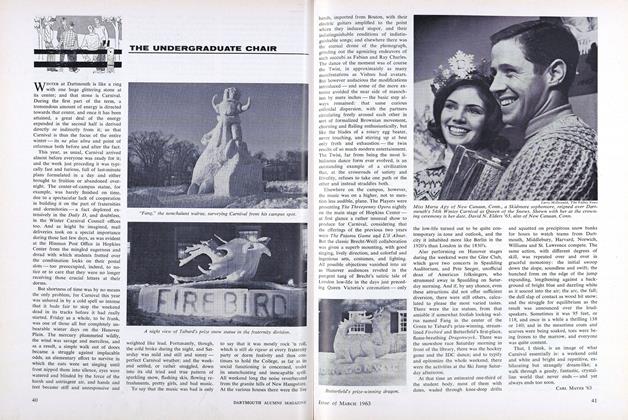

THE fall term at Dartmouth this year evaporated like a pool of water in the sun. Everyone knew the end was near when the traditional Christmas tree was once again established in splendor on the Green and strung with lights; and during the following weeks their soft unchanging scrutiny saw the regular life of the College slowly slip away and disappear. First the Daily D ceased publication; then the Frost Plays flared up for three days and died down again; and then the tempo quickened - classes and exams were suddenly over, and the last of the students had vanished to various parts of the country, leaving Hanover to what many of them considered a long winter's sleep, enlivened only by the tolling of the Baker bells and the fall of snow.

Yet Hanover during the Christmas vacation was not the ghost town that some might suppose; indeed, the absence of the larger part of the student body seems oddly enough to have stimulated the remaining populace to new heights of merriment. Hopkins Center, we are informed, instead of taking on the air of Far Rockaway out of season, resounded all season long with the clamor of voices and the shuffle of feet, most of them small; and this diminutive patronage was further indulged by special performances of The Wizard of Oz in the Center theater and by a three-day Christmas party thrown by the Canoe Club for eight small boys, a party featuring everything from ice skates, courtesy of Campion's, to magic tricks executed by Dean Thaddeus Seymour.

Yet if this latter affair impresses one as evoking a brilliance verging on the hallucinatory, for sheer spectacle it must have been eclipsed by the carol ceremony held on Christmas Eve in front of Hopkins Center, when, we are told, the balcony and plaza were filled with a jolly throng of adults and children who intoned the strains of Good King Wenceslaus and The First Noel under the direction of Paul Zeller, with (and note this) organ accompaniment provided by a real, live, freezing organist. Such lavishness staggers the imagination, and is sufficient proof in itself that Hanover is far from being a dreary and somnolent rural retreat at those times when the College is not in session.

Elsewhere in the world, to be sure, those connected in whatever way with the Dartmouth community were just as festive as that memorable group at Hopkins Center, though perhaps in different ways; but as a check to excess rejoicing, the former, unlike the latter, had to ponder the vexing problem of returning to Hanover at the end of the holidays, and there were certain considerations that did little to facilitate an answer. Toward the end of December, to be more exact, students living on the Pacific coast and in the Western states heard depressing reports of record snowfalls on the Eastern seaboard, and horrifying details were bruited about: countless cars, buses, and hay wagons, it was said, were marooned in drifts, stranded Vermonters were gnawing table legs and chair rungs while waiting for parachuted supplies from helicopters to succor their hunger, blizzards had overwhelmed entire villages in Maine, occasionally to the detriment of the state, and worst of all, New York City had been reduced to reading the Boston Herald because of the newspaper strike.

Fantastic stories, all of them; but it soon become obvious that they were true - except for the rumor about New York City, which was manifestly absurd. Those who had reservations on flights leaving for the East on New Year's Day despaired, or perhaps merely shrugged their shoulders; but as it turned out, their concern was superfluous, for miraculously enough, everything cleared up when it came time to return to school, and upon arrival at Idlewild there was no discernible evidence of bad weather, outside of a few fifteen-mile-an-hour gusts that made landing a bit rough on the cemicircular canals and an ill-tempered stewardess or two.

Yet farther north the snow was blatantly visible, and the trek back to Hanover must have been singularly cheerless for the majority of students, when one considers the less-than-appealing combination of dismal cold, obstructing drifts and dangerous ice, and three modes of transportation each, in its own unique way, odious under the conditions. If you traveled by car, there was the problem of the frequently second- and third-rate roads that converge on the College, most of them cunningly constructed to buckle instantly at the first sign of frost, and all of them as slippery as a terrazzo floor when wet — not to mention the monotony of the journey and its concomitant peril, nodding off at the wheel with miles to go before you sleep.

Or, if you chose to hop up to Hanover via Northeast Airlines, you had to deal with uncertainty raised to a fine art: Northeast cancels its flights at the least hint of a storm - a flare-up of a pilot's arthritic knee is often enough to send them into a panic - and it follows an elaborate if sometimes mystifying ritual in divulging information on changes in schedules. It also evinces an amazingly casual, folksy attitude toward running an airline, as witness its providing the cabins with ancient copies of Post and Look, for all the world like a dentist's waiting room, and allowing its stewardesses, amiable, expansive souls that they are, to summon you back to the plane after a stop in Manchester by hallooing from the door of the plane.

Traveling by train, though, was perhaps the most disheartening of all, since the only line servicing Hanover is the New York, New Haven and Hartford, which is now in a decline that threatens at any moment to become complete collapse. Rarely, if ever, does it depart and arrive on time these days - the personnel and the very engines themselves appear to be afflicted with some sort of vascular disease rendering them at once inflexible and lethargic, and the frequent and lengthy pauses at every town boasting an empty warehouse seem to indicate not so much solicitude for potential passengers as desperate efforts to build up enough wind to continue on to the next whistle stop.

One of the longest of these pauses, furthermore, is at Springfield, Massachusetts, which quite possibly possesses the most hideous railroad terminal east of the Mississippi (although it cannot dispute with Rutland, Vermont the title of New England's ugliest bus depot). It is certainly beyond cavil that, when viewed from bleary eyes after midnight, with all its concessions shut down and only slot machines left to vend their merchandise, the main waiting room in the Springfield terminal is a bone-chilling sight. Huge, bleak, empty, with green paint peeling off its iron-grey walls and a grim, hollow echo resounding from its ponderous arches at the faintest sound of footsteps, it calls to mind the hastily, sullenly fabricated mausoleum of a petty despot. After a stopover in the Springfield station, is it any wonder that the crowd of Dartmouth men disgorged at White River Junction should be wan and listless?

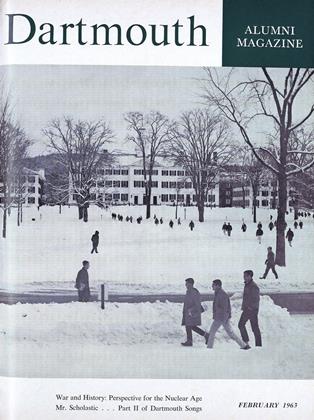

Despite such obstacles, everyone made it back, physically if not spiritually whole, and on January third, with the College knee-deep in acres of still immaculate snow, the Winter Term got under way. Classes resumed; friend greeted friend anew; stories about the holidays were exchanged; fall grades were lamented or envied; and skis were waxed and readied for the slopes. The new postal distribution area in Hopkins Center was inaugurated, and for the second time, someone walked through one of the floor-length windows near the Center entrance. Dartmouth was returning to normal.

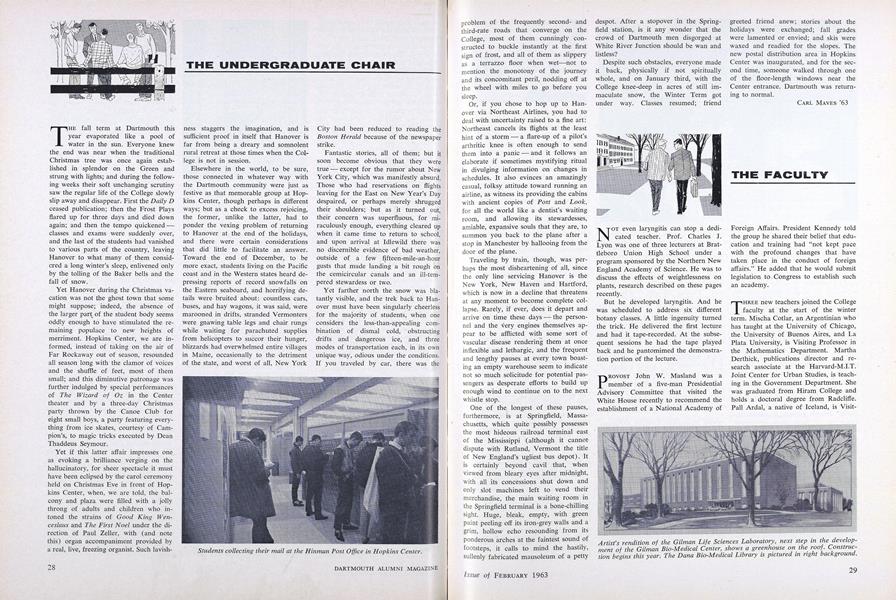

Students collecting their mail at the Hinman Post Office in Hopkins Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

February 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

February 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND HISTORY

February 1963 By LOUIS MORTON -

Feature

FeatureMR. SCHOLASTIC

February 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1963 By WM. W. FITZHUGH JR., DAVID D. WILLIAMS

CARL MAVES '63

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

OCTOBER 1968 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1963 By CARL MAVES '63