Nathaniel Merrill '48, Who Studied Abroad as a Reynolds Scholar, Enjoys a Creative Role with America's Famous Opera House

NEW YORK CITY'S Metropolitan Opera is a hall of contrasts. Red plush seats and gold decor throughout the many-tiered auditorium. Stark, colorless halls, offices, and practice rooms backstage. The black and white starched correctness opening the season and the faded blue of the stagehand's shirt rumpled in an attitude of studied disregard of aria after aria.

Splendor on stage. The golden setting of an Egyptian palace is magnificent against the brilliant blue of the cyclorama. But outside on 8th Avenue, not more than twelve yards away, other sets, other great spectacles, stand lifeless and forbidding, tied together to withstand the elements and the constant routine of hauling.

Within the Met, filling one entire Manhattan block with its exterior gloom, are bright, vital young men and women, among them Nathaniel Chase Merrill '48, who are creatively employed today on operatic works composed sixty years or more ago.

That the Met truly is a hall of contrasts was even more apparent in a brief wait for stage director Nat Merrill to arrive. The time was a little before 8:30 p.m., and the place was the barren excuse for a reception room just outside the Met's executive offices. The benches, reminiscent of those once offered in the vanishing northern New England railroad station, are functional. They discourage loitering.

Verdi's Aida was in progress on stage. The performance before a sellout audience in the lush auditorium was graciously relayed by loudspeaker to this backstage niche. Praise be it was! Leontyne Price was singing the title role. Her voice is lovely, exciting. Even the hardwood benches seemed unimportant in the grandeur of such a voice. It was disconcerting though to find that others in the room seemed not to share this concentration. Neither the receptionist nor her assistant seemed to be aware that Grand Opera was onstage just a few yards away! The grand concern of the moment for this pair was buzzing Rudolf Bing in and out the backstage door. Mr. Bing's rather dour expression and brusque nod gave a newcomer the impression that all was not as well as it sounded. But perhaps it was a hurried dinner for moments later the wildly appreciative applause replaced the orchestral sounds as the first act came to an end.

Basso Ezio Flagello, singing the role of the King and handsomely dressed for the part, opened the stage door in all his majesty to request that someone be sent for a cup of coffee. A messenger boy was off and running. A member of the chorus, a beauty direct from the Ancient Nile as recreated on the Met stage, darted in with a swish and a whirl to mail a letter. Her colorful garb brought a moment of Middle Eastern mystery to the drab room that was too quickly dispelled by her distinctly Midwestern accent.

The billboard listed the next day's schedule: Full dress rehearsal for DasRheingold, N. Merrill, stage director; Leinsdorf, conductor; principals, London, Dalis, Madeira . . . and many others. The opening was scheduled for Saturday, three days away. This was the second of four Wagnerian Ring operas being directed by Nat Merrill this season. Merrill was also scheduled for a lesser rehearsal in connection with Die Walkure. But that opening was more than a week away. Das Rheingold was the "new" opera for this particular week.

Then, Mr. Merrill himself. One must be careful at the Met to specify Nathaniel Merrill. There are several other Merrills. At first glance one would not immediately associate Nat Merrill with theatre or music. He is about average in height and weight, mild-mannered, a ready smile, and very well dressed - no beard, no beret — just a nice sort of fellow one feels at ease with. He is not at all like one of those "theatre types." But perhaps appearances can be deceiving. Nat Merrill sans beard or beret is still very much the creative individual. For Merrill creativity, even more than an intimate knowledge of music, theatre, and visual artistry, must be his stock in trade. Stage director Merrill must have this varied technical knowledge on hand, but the creativity is essential to the fusing of the techniques of all these art forms in the production of an opera.

WHERE does the stage director fit into the operatic scheme of things? How does Merrill differ from his "cousins" in the legitimate houses several blocks north on Broadway? The operatic stage director, like the legitimate theatre director, is responsible for the planning of everything that occurs on stage. He relinquishes responsibility only momentarily during the performance itself when the stage manager sees to it that the production unfolds as the stage director has planned and rehearsed it.

Nat Merrill begins his planning long before the first rehearsal, and wisely so, for once rehearsals begin there is little enough time to accomplish all that must be done in that regard. From the start he must take into account such diverse elements of production as scenery, lighting, costuming, choreography, the temperament of the principals and the number of people in the cast. But most important, of course, is to coordinate all this with the conductor.

The music is always the first concern. In this lies the principal difference between the operatic stage director and the theatre or screen director. In opera the timing has been specified by the composer. The pacing is therefore dependent upon the music, something that cannot be adjusted for an inspired piece of stagecraft. When the composer has set down sixteen bars, Merrill states emphatically, that means sixteen bars - and the composer has the conductor as a musical policeman to make sure it comes out sixteen bars. Merrill must find some other way to blend his ideas and the composer's pattern of musical development. This is restricting, of course, but for Merrill it's also fascinating. This is a good part of the challenge of being an operatic stage director.

Such restrictions are not always the case, however. In the productions of modern opera it is possible for the comp oser and the director to work together in creating stronger action on stage. In Grand Opera, Merrill says, one is very seldom able to change the tempo. When the composer is dead, the young director observes, it's come to be considered morally wrong to change the pace. Creative stage direction within these limits therefore requires a disciplined approach, something akin to the fashioning of a well-made poem.

Obviously Merrill must have had extensive formal musical training to do this job. He has, as have most other good operatic stage directors. There are a few very special exceptions, among them Cyril Ritchard and Tyrone Guthrie. Where do men like Nathaniel Merrill come from? How does one become a stage director in Grand Opera . . . and especially, how did such a young stage director find his way to America's great opera house?

Nathaniel Merrill first became interested in opera in his senior year at Dartmouth. Music was the focus of his academic life at Dartmouth, and his new interest in opera was therefore a natural one. He was majoring in music composition, and his ability with the clarinet played an important role in his extracurricular hours. But in June 1949, A.B. degree in hand, he had little idea of the direction he wanted to take. His developing interest in opera prompted him to accept a summer job assisting Boris Goldovsky in the opera workshop at Tanglewood, Mass. At summer's end he knew what the next step had to be: continued study as a special student of opera under Mr. Goldovsky at the New England Conservatory of Music and at the same time graduate student in musicology under Professor Karl Geiringer at Boston University.

Because he liked what he was doing he worked at it hard, and it wasn't long before his competence was recognized by appointments in 1951 as a faculty member in opera at Tanglewood, as a faculty member for the Boston Univers ity opera workshop, and as the associate technical director for the New England Opera Theatre in Boston. In 1953 he was awarded his Master's degree in music. His graduate thesis was based on the Bizet opera Carmen. Poor tragic Carmen. Merrill now calls her a good example of the flimsy static character lacking dramatic development that weakens so many operatic stories. She's downright dull, Merrill says, compared to Don Jose who is forced to develop from soldier to renegade to criminal. It could be quite romantic to say that once Merrill had his M.A. safely in hand he turned aside his Carmen to look longingly eastward across the Atlantic. But the simple facts are that European study and practical work m opera abroad are the logical. . .

almost essential. . . next steps toward a career in this field. Here Dartmouth again entered Merrill's life, providing him with the means for his advancement by awarding him James B. Reynolds Graduate Fellowship for foreign study in opera and opera production. The Reynolds Fellowship offered few strings and great freedom for Merrill to set out on his relatively, and necessarily, vague plan to study opera in Germany.

It was Dartmouth therefore that made this next big step possible, and for this aid Nat Merrill is extremely grateful. The enrichment of the Reynolds years could be attributed in part to that poor dull gal Carmen, for it was because of a common interest in this Bizet work that Merrill became well acquainted with stage director Dr. Herbert Graf, conductor Max Rudolph, and chorus master Kurt Adler. Through contacts provided by these men Merrill was invited to join the Hamburg State Opera as assistant stage director for the 1953-54 season. The next season he accepted similar responsibilities at the Hessian State Opera in Weisbaden. The experience gained in Germany, and in a brief period in 1954 as assistant stage director at the Glyndebourne, England, Opera Festival, was extensive. Dartmouth's investment of its Reynolds Fellowship funds in Nat Merrill certainly must be termed a very wise investment, if only for the reason that upon his return to the United States in 1955 Merrill was immediately invited to join the Met staff as an assistant stage director.

Once again Dr. Graf was helpful in placing Merrill's credentials before the proper people, but there can be no doubt that solid accomplishment, and that alone, was the entrance key to the United States' royal palace of Grand Opera. Two years later Merrill was named a stage director at the Met.

THE Metropolitan Opera has a 28-eek season in New York and a seven-week tour. During this period Nat Merrill expects to work, and actually does work, close to a full seven-day week - night and day. Such a schedule is a necessity for a stage director responsible for at least one third of the opera company's repertory for the season. Despite the lack of free time Merrill relishes this schedule. Demonstrating either his math minor interests as an undergraduate or his pleasant positive approach, Merrill quickly points out that there are few who have a seventeen-week vacation each year. Nat Merrill may have this chunk of warm weather away from the Met, but it's certainly not away from opera.

In 1956 and 1957 he accepted an invitation to use his "vacation" time as assistant stage director for the Salzburg Festival in Austria, a world-famous musical annual. In 1958 he was invited again to Salzburg, this time to be stage director for the first European performance of Samuel Barber's Vanessa. That same year he was stage director for a new production of Strauss' Ariadne auxNaxos at the Washington, D. C., Opera Society and held a similar post of responsibility at the Central City Opera in Colorado for Offenbach's La Perichole. He returned to both Washington and Central City the next year (1959) to do Douglas Moore's American opera TheBallad of Baby Doe and Die Fledermaus out west and Verdi's Falstaff and Mozart's Don Giovanni in the nation's capital. The next two summers he returned to Central City .to direct a variety of productions. In addition he was invited to Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1960 to stage direct a new production of Puccini's Madame Butterfly at the International Festival there. For Nat Merrill such invitations provide a wonderful way to keep himself busy during the seventeen-week Met layoff - and the Met doesn't appear at all unhappy that he chooses to while away the idle hours this way.

Merrill finds one great appeal in opera at Central City and at festivals, an appeal that will draw him again and again to these smaller opera houses. And that is the opportunity to do new works in new ways. At the Met the director, or any other principal in the production, can't afford to experiment. The costs of sets, costuming and all are such that the opera once done new or redone throughout is sure to be in the repertory for fifteen years, if not longer. At Central City the production is performed only one season and then discarded. By comparison and by necessity the Met is conservative, Merrill notes. The average German theatre, he reports, is far ahead of the Met in the number of new productions. And that's true in other European countries too. La Scala, for instance, has staged five new productions of Traviata since the war.

Much of Merrill's work therefore is in restaging repertory pieces as they had been done before. If the original stage director was someone other than himself, Merrill must attempt to follow faithfully the style initially set. Of course, he would attempt to correct obvious deficiencies, but in the very brief rehearsal time allowed in preparing a work in the repertory there is little opportunity to do much more than make sure the work will be presentable and ready for the opening... in the same shape as the previous season.

A second part of his job consists of completely redoing older productions for which sets and costumes exist, but which have been out of the repertory for several seasons. Here it is a question of restaging the opera within the existing physical form, but according to Merrill's desires. This is usually done with new singers who never appeared in the older production. This is the case this season with Merrill's much-praised work with TheRing of the Nibelung.

"In Europe when one does a new Ring," Merrill states, "one normally does one opera a year for four years, then one puts them together in repertory." This certainly is not the case this season at the Met.

The sets and costumes for this season's Ring are the same ones used in 1957 when the operas were last staged by Dr. Graf. Because the singers were all new and the rehearsal time extremely limited there was little opportunity for scenic changes. But the staging was a new study by Merrill from beginning to end. The success of the Met's Ring this season is a matter of public record in the daily newspapers and in other critical columns.

However, what really matters to Merrill is the audience reaction. This season's Gotterdammerung received 30 minutes of curtain call applause. Siegfried and Das Rheingold received similar ovations. Why does the popular opinion mean so much to Merrill? Simply because for Merrill Grand Opera is entertainment, certainly a highly specialized form of entertainment but definitely not an ART that exists for its own sake. Grand Opera, he feels, must offer satisfaction . . . inspiration . . . qualities that must and do have a direct effect for the audience. "Too often opera is approached as an art form," he says, "and opera on those terms is poor opera." He went on to explain how Mozart operas, for instance, were written strictly as entertainment and not as art pieces. His expression seemed to add "you'd never know it the way they're done now!"

Acceptance of Grand Opera, Merrill states, relies on the acceptance of the distortion of the time element. It would be unthinkable in modern theatre to have an actor stop and give you a ten-minute recital, but in opera dramatic moments are stretched out to give expression in lyrical terms. This can be terribly exciting as anyone knows who has listened to Joan Sutherland in the "mad scene" from Lucia. The problem for Merrill is this: do you let the character stand there and sing or try to work some dramatic action into the scene? As an opera stage director Merrill must always try to express the music first and foremost, but that doesn't mean he should shut his eyes to greater possibilities in combining the music with meaningful dramatic action.

THE greatest test of the stage director is in the handling of a completely new production. Merrill has had two quite different tests of this sort in L'Elisird'Amore and Turandot. In both he received praise for his direction, and the operas are now very popular in the Met's repertory. In Elisir Merrill had a relatively small cast of sixty, but the Donizetti opera is a complex one and required two months of preparations on his part before the first rehearsal. From that point there were three hectic rehearsalfilled weeks before the premiere. The success of his efforts is now part of Met history.

For Turandot it was quite a different story in the beginning. Stage director Yoshio Aoyama was scheduled to handle this new production, but he fell ill and Merrill, on the strength of his success with Elisir, was named to continue the planning for the production. He had never seen the opera before. This, strangely enough, delighted General Manager Bing who felt that Merrill would not approach the opera with preconceived notions. Merrill moved from home to hotel to learn the opera, but even with this concentration he hadn't even looked at the third act when the first act rehearsals began four days later. The logistics in scheduling rehearsals at the Met are fantastic, especially in the scheduling of rehearsal times for the principal singers. A Corelli, Nilsson or Tebaldi cannot be expected to rehearse with a piano on a new production in the afternoon, then sing in a regularly scheduled repertory piece that evening. Most major artists refuse to come into the opera house for one day before and after a performance. Ballet must be started along with the singers, both choral groups and individual parts, and all must reach the full rehearsal stage at the same time. For Turandot Merrill worked closely with the ballet mistress, even to having her study Chinese classical dance movements frantically for four days to arrive at the type of dance movement he envisioned. This was the first Met production of this Puccini opera since 1930, and it was received with acclaim by critics and audience alike in its premiere last season and this season too.

Birgit Nilsson sang the demanding role of the princess Turandot and was also one of the principals in the Ring. Merrill calls Miss Nilsson the outstanding Wagnerian singer of our time, adding that she knows exactly what she is going to do when she gets to the stage. "But she approaches each performance as if it were the first time she's done it," he adds. In the past Merrill has worked with Callas and Tebaldi and if not for the strike that threatened to end this year's performances Merrill would be working again with Tebaldi in a new production this spring. This production of Cilea's Adrianna Lecouvrer will be mounted in the 1962-63 Met season, and in addition Merrill will stage a second new production, Wagner's Die Meistersinger, a great favorite of opera lovers. Merrill will also do a refurbished Pelleas and Melisande next season with Ernst Ansermet as conductor.

When the Met moves to the Lincoln Center in 1964 it will have the best technically equipped opera house in the world. There is no doubt that the young director is looking forward to the day when he will work on the Center's stage, having rehearsal space aplenty and no worries about sets getting jammed in midtown traffic. Of course the glamor of the old opera house will be missed, Merrill says quietly, then adds quickly the very practical note that although it would be wonderful to save the old Met no one except the Federal Government could afford it. Critic Joseph Wechsberg in a recent Times article on the "Grand Price of Grand Opera" had this to say: "The fact is that no opera house on earth ever managed to break even, let alone make money. Grand opera is just too damn expensive to produce." Wechsberg endorses public subsidies (something Europeans have long had); to which Merrill adds that the grand day of three tiers of boxes subscribed for the season is gone and that government subsidy may have to be the long-term answer.

Expensive it may be, but there are many who love it. Among them stage director Merrill. And Merrill believes that opera is more popular than ever before. He cites the marvelous results in building young audiences through opera workshops at colleges and universities. "They are forced to make opera entertaining," Merrill states, adding that too often Grand Opera is presented as an Art simply because it's done here in a foreign language. Often, he says, it's made so mysterious that the student attitude is akin to "the hell with it" or a feeling of being out of it all because it's all so far above one and so unspeakably good.

This isn't Grand Opera at all, Merrill emphasizes. Again he states his contention that Grand Opera should be entertainment. For the , Metropolitan Opera audience the entertainment focus is somewhat different than at Central City, he says. At the Met it's just plain difficult to make an audience laugh. "They want corpses, lots of bodies lying around at the end."

NAT MERRILL, man of opera, is also in good standing as a family man and as a Dartmouth man. In fact, there are few alumni who can claim such a distinguished Dartmouth background. Nat's father was Henry W. Merrill '13, his brother Henry W. Merrill Jr. '39, his cousin Robert Chase Jr. '41, his uncle Robert Chase '15. His grandfathers were Arthur H. Chase '86 and Louis C. Merrill '73, and his great-grandfather, William M. Chase, Class of 1858, was a Trustee of the. College.

In 1951 Nat Merrill married an attractive singer and fellow student at the New England Conservatory of Music, Miss Barbara Jo Curry of Evanston, Ill. They now have two children, Linda, four, and Henry, eleven months, and live in New York City's Greenwich Village, a block or so north of Washington Square.

Nathaniel Chase Merrill has moved fast in his chosen career, from a Reynolds Fellowship student to stage director at one of the world's great opera houses in less than a decade. The next decade promises to be even more interesting, especially when the Met, the hall of contrasts, becomes one with the Lincoln Center, the creative hope of the future.

FOR generations Velvet Rocks have cast down upon Hanover Plain the echoes of Dartmouth students' shouted eulogies to Eleazar Wheelock, a very pious man. With each fading note across the hurried years, the doughty clergyman's immortality, already firmly rooted in the gleaming presence of the College on the hill, is reaffirmed and his name "goes again the well-remembered round." For most of us, however, immortality takes on a less imposing aspect, and we are forced to rely chiefly on the übiquitous miracle of methodical partition of our chromosomal material and the fateful repositioning of the physiologic IBM card that is called inheritance. The same was true for Wheelock, yet his descendants and their names and their deeds have been nearly eclipsed by the fame and pervading influence of the founder of Dartmouth College.

Where are they, then, these carriers of the genes of the Reverend Dr. Wheelock? Do men still live who bear the Wheelock name and rightly claim that they are descended from this vigorous New England educator, Yale man, and divine, twice married, the father of eleven children? Or has the line "daughtered out," to quote the late Prof. Leon Burr Richardson, who knew much of these things? He thought it had and maintained that the blood of the founder of Dartmouth College flowed only in the veins of men and women who had inherited his genetic character but not his surname.

The tapestry of refutation is a long one and is woven of many things: of a small stream in Ohio called Boat Run, of Indian wars on the Illinois prairie, of death on the endless Texas borderlands, and of stout brothers fighting in the Confederate armies. But above this confused melange flies the eagle of undoubted fact and the star and bars of the flag of Texas, for although Eleazar Wheelock nourished the heathen to his academic bosom long ago, his grandson fought them tooth and nail with gunpowder and frontier cunning along the muddy banks of the Brazos and the Sabine, and his descendants live there still.

But we must go back to pick up this thread, made tenuous by the fact that only one man successfully bridged the gap between Now and Then - Colonel Eleazar Louis Ripley Wheelock of Wheelock, Texas: pioneer, Texas Ranger, Indian fighter, and founder of the town in Robertson County, Texas named for him.

Besides his daughters, Eleazar had four mature sons, all born in Connecticut, three of them by his second wife. They accompanied him to Hanover in 1770 and were at his bedside when he died in

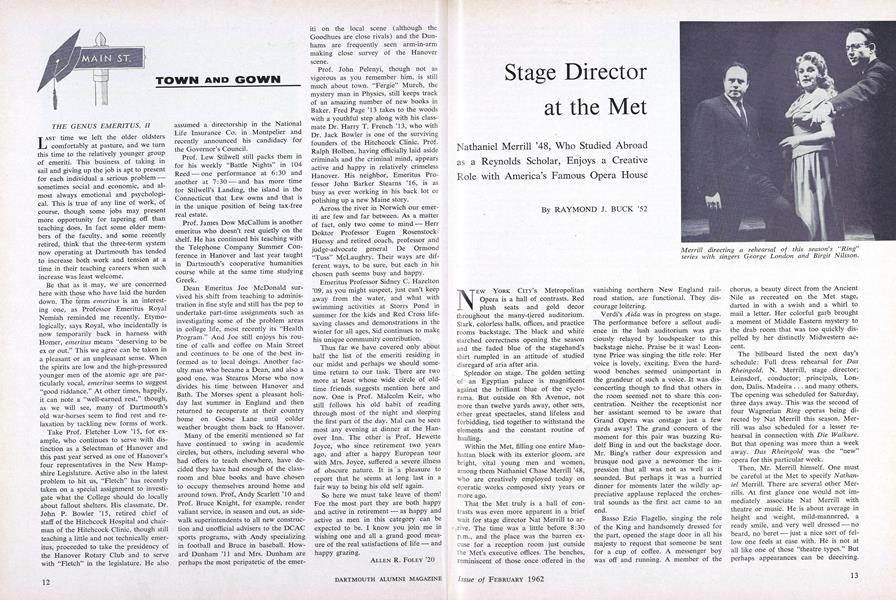

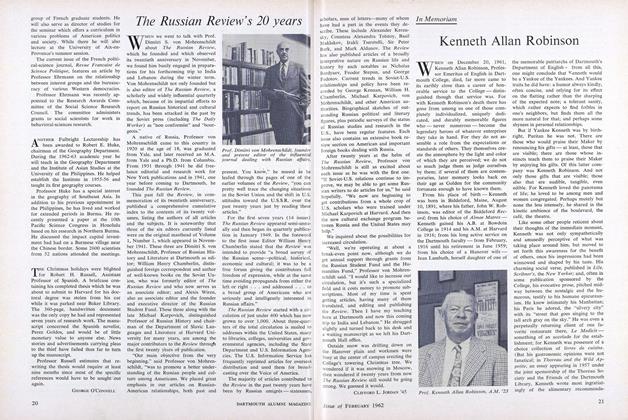

Merrill directing a rehearsal of this season's "Ring"series with singers George London and Birgit Nilsson.

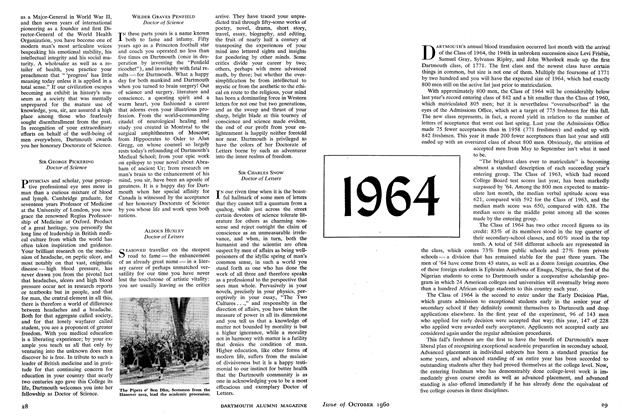

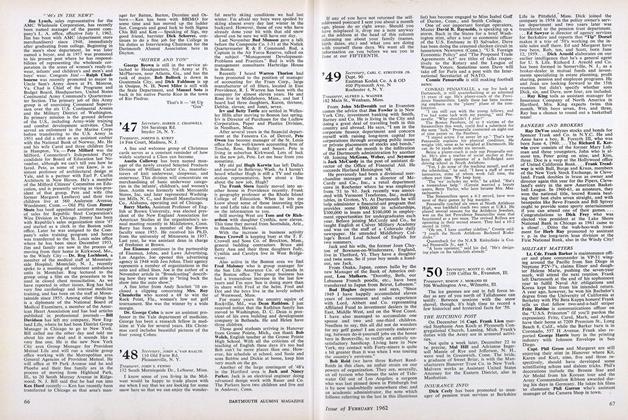

Merrill relaxing in Colorado with hiswife Barbara Jo and daughter Linda.

Stage director Merrill (left) with scenic designer Cecil Beaton, conductor LeopoldStokowski, Met general manager Rudolf Bing, and tenor Franco Corelli duringa rehearsal of "Turandot," the Met's great success of the 1960-61 season.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Very Old and the Old

February 1962 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Feature

FeatureKenneth Allan Robinson

February 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Feature

FeatureELEAZAR WHEELOCKS, IN DIRECT LINE, STILL LIVE – IN TEXAS

February 1962 By SEYMOUR E. WHEELOCK '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1962 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1962 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON, JAMES B. GODFREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

February 1962 By CHARLES F. McGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY, H. SHERIDAN BAKETEL JR.

RAYMOND J. BUCK '52

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Cold War and Liberal Learning

November 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMara Rudman '84

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWHEELOCK’S FULFILLING OF THE SCRIPTURE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

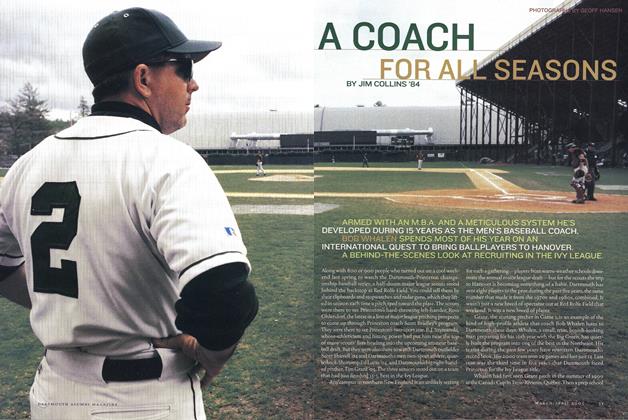

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

Mar/Apr 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDARTMOUTH IN THE MEDIA

OCTOBER 1990 By Peter S. Prichard '66 -

Feature

FeatureCan the Summer?

OCTOBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham