Some Highlights of 165 Years of Med School History as Told in the Inaugural Talk of the Dartmouth Medical Student Lecture Series

EVEN as late as 1769, when Dartmouth College was founded, until shortly before the Medical School existed there was no medical organization whatsoever in New Hampshire. The training of a man who wished to practice medicine was to serve as a voluntary apprentice under a practicing physician, who created his own curriculum, mostly without offering opportunity for any anatomical dissection, carrying it on until he thought that the neophyte was qualified to practice medicine. No other regulations at this time existed to make certain that the budding doctor was properly qualified to be a doctor. This system had produced its doctors, good and bad, for hundreds of years, until finally it was superseded by some formal organization of the study of medicine at varying periods in Europe, later of course in this country.

Three medical schools existed in this country prior to the founding of Dartmouth Medical' School, of which Harvard Medical School was by far the oldest, followed by Pennsylvania and Columbia University Medical Schools. (The last changed its name and suffered an interruption in its activities.) Dartmouth Medical School appeared near the end of that century in 1797, the fourth in this country, and the third which has continued without interruption to the present day.

Of the many doctors who have been members of its faculty during its first eighty years I want to speak briefly of five. In one way or another I think they have contributed greatly to this school and are responsible in large measure for its early existence and development, along with others, also famous, or important in its growth, of whom there is not time to speak. The first of this group - and the most important and the most famous - is the man who almost singlehandedly was responsible for the founding and early life of D.M.S. - Nathan Smith.

Born in 1762 in Massachusetts, he early came to live in New Hampshire, not far from Hanover. He first appears as a young bystander, asked to hold the leg of a man who was being readied for its amputation. Whether this successful operation by the surgeon without an anaesthetic was the cause of Nathan Smith's becoming a doctor or whether the embryo doctor in Nathan Smith was the reason for his holding the leg, I don't know. But shortly he began the study of medicine, practiced his profession near Hanover and later in the town itself, and quickly proved himself to be an outstanding physician and surgeon. He received medical degrees from the school he was to found in Hanover and from Harvard Medical School, as he became the best known doctor in this state and still more widely as his reputation increased.

He realized the value of a medical school north of Massachusetts and was able to persuade the Trustees of the young Dartmouth College that here was the place to establish such a school. With the newly created New Hampshire Medical Society (which he helped to found) he was able to persuade the New Hampshire Legislature to loan the College $3,450 towards a medical building, on land contributed by himself. Here for thirteen years he was the sole member of his faculty, except for two minor assistants for short periods of time. Before the Medical Building was built, and completed in 1811, classes were held in the "Medical House," a dwelling just west of the present Old Medical Building, and in the north end of Dartmouth Hall, Room No. 6 (used as lecture hall, dissecting room, chemistry laboratory and library, along with a second room granted him for the early years). The Medical House is still in existence as the main part of a house in the southwest part of this town at No. 10 Pleasant Street.

As the sole and certainly most important member of the faculty Nathan Smith gave a course of lectures five days a week for ten weeks, covering the greater part of the curriculum: Anatomy, Surgery, Chemistry, Materia Medica, Physiology, and Theory and the Practice of Medicine. On his very frequent trips into the surrounding country to see patients, he had with him one or more students, all the party on horseback. He quizzed and instilled medicine into them besides conducting a sort of surgical or medical clinic at the houses he visited, often to perform surgical operations. Such was the lot of the preceptor of those earlier days.

As you can understand, it is not surprising that Nathan Smith was said to be "50 years ahead of his profession, a good observer and reporter," besides being a most successful practitioner of the profession he taught others to follow. He did especially notable work in being among the first to distinguish typhoid from typhus fever, to improve the treatment of dislocation of the hip joint. One episode must not be omitted here, to show his concentration when at work. In the case of some abdominal surgery, as the relatives watched the operation, he was heard to murmur, "What! What! have I cut a gut? They might as well make his coffin now as ever." He left Dartmouth in 1813 for Yale. Surely he must have created a record by the fact that he founded or helped found four medical schools, Dartmouth, Yale, Bowdoin, and Vermont.

His departure brings the name of the second member of our faculty of whom I wish to speak - Dr. Reuben D. Mussey. He succeeded Nathan Smith, and, like him, for a time filled the role of teacher of most of the subjects in the curriculum. During his time the faculty increased to four. He came to Hanover a graduate of Dartmouth, with medical degrees from Harvard and Pennsylvania. He, like Nathan Smith, was eminent especially as a surgeon, almost, if not quite, as active and well known as was his predecessor, and very much of an investigator covering several fields outside his specialty. He taught here from 1814 to 1838, when he left Hanover for Cincinnati, Ohio, even founding later a medical school In that state. He took active part in Hanover's affairs besides his medical professional activities. He was a vegetarian, a prohibitionist, an anti-tobacco protagonist, and an accomplished musician, playing the first double bass viol to come to New Hampshire and being one of the founders of the Handel Society of Dartmouth. . . .

Oliver Wendell Holmes, my third professor, followed Dr. Mussey as teacher of anatomy and physiology among a faculty of six, but only for a period less than three years, following which he went to teach the same subjects at his alma mater, Harvard. During the first of his three years under Dartmouth auspices he prepared anatomical specimens. Among these was an excellent dissection to show the cranial nerves in the cranial cavity and as they are distributed to their structures outside the brain box. This we are happy to have intact in our Museum, despite the fact that it was made before there was knowledge of a practical means for preserving specimens, save by dessication. Holmes is better known by most people as an author. In fact TheAutocrat of the Breakfast Table was largely written during his service at D.M.S., perhaps elaborated as he sat at his first meal of the day at his table at the Hanover Hotel. In addition to his medical duties he wrote the catalog for the Medical School and read a poem at his first Commencement celebration - the latter being, so far as known, a unique service among the professors of anatomy.

After leaving Hanover, Holmes became famous not only for his literary works, but for his work in his own profession. He wrote a rather trenchant paper on homeopathy, and among others one on "childbed fever" or puerperal fever, then a very common and often fatal fever following infection of women during labor. The cause, of course, was due to lack of knowledge of any kind of the cause of such infection, brought by the unknowing obstetrician. In Austria Semmelweis had discovered clues that pointed to this fact, and had started a campaign, dramatically and successfully continued by Holmes in this country through his ability to publicize the discovery by his writings. His first lecture at Dartmouth to his students of anatomy was entitled "Associate Function with Structure," still a timely subject and one which has always greatly intrigued this professor, who followed him in the chair of anatomy 72 years later.

My fourth choice of the medical faculty is Dr. Dixi Crosby, Dartmouth M.D. 1824, one of a famous Dartmouth family, including his doctor son, A. Benning Crosby, and a brother, Alpheus, Dartmouth 1827, well-known Greek scholar - all professors in Dartmouth. The last was the author of a countrywide famous Greek grammar. Dixi Crosby succeeded Mussey as surgeon on the faculty and practiced over a very wide area of northern New England, constituting the third in direct succession of active and well-known surgeons in our school. Dr. Crosby established the first hospital in Hanover in a house directly opposite the Medical Building. At the latter he performed operations before the classes in the lecture room of the Medical Building, taking his patients to the new hospital for further care. His term of service lasted from 1838 to 1870. In addition to his professional qualities of such high order, he was interested in birds and insects, or as stated by one of his literary eulogists, he "reveled in pomp of groves and garniture of fields." Among his surgical experiences he was the first (or if not the first, among the first) effectively and sanely to treat the previously very difficult matter of reducing a dislocated thumb at its metacarpo-phalangeal joint, a procedure as basic in reduction of dislocation as is the method for reducing dislocation of the hip joint instead of the earlier mankilling process of leg-pulling. I can't give here the list of many almost pioneer operative methods which he practiced as one of the earliest to do so.

The last member of our medical faculty in the first half of the school's existence is Dr. Carleton P. Frost, Dartmouth A.B. 1852 and M.D. 1857, who started teaching here in 1868 and continued on the faculty until his death in 1896. He spanned the halfway mark of D.M.S., continuing well into the second half of its existence, and in many ways this was characteristic of the man, for he not only could match the abilities of the "greats" of the earlier period but he was able to advance into a later generation and had much to do with the development of D.M.S. in the later period, when change was necessary. Dr. Frost was not a surgeon but what today we call an internist; also, he was a splendid administrator and innovator. He, like Dr. Mussey, was very active in the Town of Hanover, where he not only practiced his profession, but was largely responsible for introducing the present system of water supply and was a large factor in introducing electricity into this town. (If you don't understand the importance of this innovation, you should be required to fill, trim, and use a kerosene lamp.) His most important contribution to the town and Medical School, both, was his active organization of a group, determined to build a hospital in town (for Dixi Crosby's hospital ceased to exist about 1870). It was largely Dr. Frost's persuasion that induced Mr. Hiram Hitchcock to give the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital. It was he who did much in the planning of the type of hospital it was to be. When it was first opened in 1893 it was perhaps the outstanding hospital of its kind in the country, a mark to aim at.

Dr. Frost, shortly after he came to Hanover in 1870, introduced much needed newer methods of teaching medicine at that time. He introduced the recitation class, which meant the socalled "winter term" (recitation period), and improved the "summer term," which brought to Hanover for that season a series of outstanding lecturers in most fields of medicine from well over the country. His wise moves brought the numbers of medical students up to their greatest, I think, in the entire existence of this medical school.

I well remember Dr. Frost, who looked like Michelangelo's painting of God in the Sistine Chapel, with his flowing white beard and great dignity. However, this somewhat fearsome atmosphere was dissipated when he came to see me in any time of sickness of my earlier days.

I should like to speak of other teachers of our medical faculty, many of whom deserve mention for what they brought to Dartmouth Medical School. I should like to include Daniel Oliver, contemporary of Dr. Mussey; Dr. Peaslee, teacher for 37 years; Dr. A. Benning Crosby, almost as famous as his father, Dixi Crosby, not only as doctor but as a speaker on many public occasions; and others, if only I could take the time to do so.

WHAT I have just tried to describe to you concerns the growth of Dartmouth Medical School through the first half of its existence of 164 years. Of that half of its existence I have no personal knowledge. At about the end of that time, in the late 1870's, I had hardly begun my first lesson in human anatomy by counting my own toes, as I gazed at the Old Medical Building from my own backyard, where now stands Steele Hall, the chemistry building.

As for the last eighty years or so of our own school, I will try to give you a statement of what I have personally seen from the outside or known from the inside, in about equal amounts. I hope the autobiographical approach will not seem too presumptuous on my part. Perhaps it will be the most enlightening way to picture to you the actual story of Dartmouth Medical School during half its existence prior to the present. It is a sort of "worm's-eye" view of medical education at Dartmouth Medical School before its last metamorphosis into the present full-fledged butterfly that you now know.

The first recollections I have of the existence of a medical school in Hanover go back into the dimness of my extreme youth, about 1880. I used to play in a yard just south of a five-foot solid board fence, bordering the south side of the driveway leading uphill to the Medical Building, the only medical building of those days. This substantial affair separated me from processions of men who thronged up and down the hill day after day throughout each summer, and it gave me a feeling of protection from those burly and noisy "medics" as they marched to the old lecture room to listen to some sort of fearsome talk that I shortly afterward heard emanating from the open windows.

My next association with the mecca of these pilgrims of medical knowledge, some fresh from the high schools, others from the farm, shop or business job, even graying at the temples in some cases, concerns the southern extension of the main building, whose windows were annoyingly and mysteriously opaque, or so much so that a palpitating youngster, peering through these panes into the interior, could see nothing except vague shapes that certainly stimulated the imagination. How scared I was of the Dissecting Room! Up to my college days it was a feat of real courage to walk past that room alone in the dark. Certainly my first acquaintance with anatomy and anatomical rooms was not a happy one nor any augury of the different relationships that finally evolved. My strongest asseveration of those times was that I would never be a minister, teacher or doctor. Perhaps this is one reason why I today am not entirely convinced by the stout assertion of some beardless youth in regard to what he intends to do or be in his later years. What he first abhors, he may learn to endure, then pity, then embrace.

Naturally as a result of this conditioning I entered college with a firm determination to take on all the mathematics available so as to enter the engineering profession by way of the Thayer School, and promptly gave up the idea in my junior year. Following graduation I took my plunge into the world of independence by teaching high school, a procedure that was terminated at the end of a year, and then I accepted the inevitable and entered Dartmouth Medical School as a freshman. Four years of college work was more than the necessary requirement for admission as I started the study of medicine, but the earlier courses of my four years in college were sadly lacking in many ways as a suitable premedical training, a loss I have always keenly felt. This was the transition time when medical requirement stepped up rapidly and when the medical course became a full four-year course.

The curriculum at the end of the century was very different from what it shortly became. I was introduced into the old system, an annual course consisting of a summer and a winter session. The latter began in late September, as I recall, lasting until early in April; the former began in July, continuing until well into September; and the two courses bore little resemblance to each other, save that each was concerned with medicine.

The work of the winter course, with the exception of that in chemistry, was all carried on in the Medical Building, where we met daily for recitations on assigned pages of various medical texts, or for anatomical dissection in the Dissecting Room. Chemistry was given in Culver Hall, then standing nearly opposite Topliff Hall.

In the summer the students of at least two different classes assembled every morning, six days a week, from eight until twelve o'clock, in the lecture room, to listen to four lectures in succession, in Surgery, Therapeutics, Obstetrics, Gynecology, Hygiene, Mental Diseases, Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat diseases, or Medical Jurisprudence - all these scattered throughout the summer session, sometimes two of the same kind in one morning. All these courses, some short, others long, were given by visiting professors, among the best in their fields, culled from Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Ann Arbor, Cincinnati, and elsewhere. Each student sat under these lecturers, giving the same subject each year, two years in succession, on the theory, I suppose, that what didn't enter his head the first year might seep in the second. Certainly much of the earlier lectures was over my head as I had too little background against which to place what I heard. Often the last hour — on a hot summer's day - was pretty nearly a blank and the voluminous note-taking lagged a bit, while the seats became harder and harder before noon released us, and the callosities of my ischia were at this period of my life permanently hypertrophied.

But of all the lecturers I heard, Dr. P. S. Conner stands out most distinctly in my recollection as a great teacher of surgery, as it was taught in those days, in the summer sessions of 1899 and 1900. His heavy drooping mustache, his snapping eyes, his keen tongue and his complete control of any situation in which he found himself, made an indelible impression upon me. He was a brilliant lecturer, making his points clear and easy to remember, coloring his more prosaic facts with illustrations from his own practice, or launching into some dramatic episode from his varied experience. Some of these episodes came from his life as an army surgeon in the Civil War, some from his early practicing days and some - the most awe-inspiring - from his days on the witness stand. Whenever the legal profession entered the picture Dr. Conner was the most forceful in his language, the most vitriolic, and I used to have pity for those unfortunate lawyers whose fate it might be to cross-examine this tartar of a surgeon. Brought up in the period when anesthetics were still new, and actually after having to operate as an army surgeon of the Civil "War without their benefit, he still exemplified in all his surgical work the desire for speed, so characteristic of the surgeons of those and earlier days. The slower surgery, possible and necessary today, makes it hard to realize the spectacular nature of the lightning-like performances of Dr. Conner at the operating table.

The first operation I ever saw was a breast removal by Dr. Conner for cancer at our hospital. When the patient was ready, the field of operation exposed, he poised his knife above the patient and then made two quick cuts, joined together above and below the breast, and the desired removal was almost done then and there. His most obvious delight came when a young man, hit on the head by a baseball, was brought to him in an unconscious state. Judging a trephining operation was needed, Dr. Conner took up the task with plain satisfaction, for he was not to be bothered by all the paraphernalia, fuss and disturbance of the anaesthetist. The baseball saw to that....

When the summer course was ended late in September we really went to work. We no longer listened to four lectures a day or attended the shows at the hospital, but we settled down to daily recitation for most of the morning and laboratory work in the balance of the morning and for the afternoons. Evenings were spent, running well into the nights, in studying those long assignments in anatomy, histology, physiology, bacteriology and pathology, obstetrics, surgery and medicine, the principal studies of the curriculum during my three years of the most intensive work I had ever imagined.

The microscopic work was handled by Dr. H. N. Kingsford, very recently added to the faculty. Some months later students in a slide examination found it hard to differentiate between a slide of hepatized pulmonary tissue and the very similar structure of a bologna sausage that somehow slipped into the group of slides handed out for a test.

Physical diagnosis, therapeutics, practice of medicine and some lesser subjects, possibly, were taught by Dr. John M. Gile, for so many years the outstanding surgeon of a large part of New Hampshire and Vermont, to become later also Dean of this school. His straightforward and clear presentation of any matter of which he spoke, whether in the form of a brief lecture upon hernia or in a discussion of a hypothetical medical case and his ability to draw upon a tremendously large practice, are the impressions that remain with me as a student in his classes. Despite the long hours spent driving over the neighboring country (later being driven by his son, Dr. J. F. Gile) by day or night, performing countless surgical operations on his patients, laid out on the kitchen table or on the operating table of the hospital, always extremely busy, it was almost always a sure thing that at eight o'clock in the morning he would be found sitting in his armchair before his assembled class in the Museum — although we often suspected he had had little or no sleep the night before. He never failed to be ready for the assignment to the class, and he always maintained the interest of each student to the end of the hour.

At the top of the list of medical teachers was Dr. Gilman D. Frost, "Gil" to most of us, son of Dr. C. P. Frost. In his method of teaching he stands paramount, for he was in my experience the arch user of the Socratic method. He not only fired questions at us every day for that absorbing and heart-breaking hour of recitation, but such questions as were devilishly calculated for the very purpose of making us think beyond the conclusions evident in the facts of our previous night's study. Try as I might it seemed to me that never did I answer Gil's questions satisfactorily. Always I strained my puzzled brains to find the solution, and always he went elsewhere to find the exact words and ideas he sought. I would learn every fact of my anatomy lesson, memorize the branches of the smallest arteries, making up absurd mnemonics for the purpose (a practice I later came to anathematize), coming primed for the fray for each recitation, and always, it seemed, I would leave it disappointed. With a little charity to myself I think this procedure was a deliberate part of his outrageously tantalizing system, but my agonies were nonetheless great, and my respect for his invincible knowledge and logic was almost as high as they deserved. Often leaning on his hand at the desk, his face gray with pain and weariness following one of his frequent migraine attacks, he never missed a class and he never faltered in his rapid-fire questioning — and we never failed to feel that we had flunked once more. Strangely enough we bobbed up serenely the next time, ready for the slaughter.

In obstetrics and in practice of medicine it was always the same thing for the students of his classes, an hour of concentrated thought and a clearer picture of whatever was under discussion. Never once were we asked, it seemed, to give a plain fact out of our worn texts, but when we finished discussing typhoid fever (an obsolescent disease today in this region) or the mechanics of a face presentation, we did acquire some understanding of causes, the course of events in such conditions, and the reasons for the results that might ensue. "What did the old cow do under such circumstances?" was a question that embarrassed me, as it flattered my past experience for I had not the slightest idea. But, if the old cow did so and so, I was sure she and Gil were right and that probably he had so instructed her. . . .

Somewhat later, to my amazement, Dr. Frost told me that, with "Rastus" Wilder of my class, I was to be demonstrator of anatomy the following fall for the freshman medics. And so, after a display of ignorance throughout my Frost anatomy course, I was launched on what proved to be my lifetime job. For this work for each of the two following years I received the sum of twenty dollars.

FOLLOWING the completion of my medical work at Dartmouth and my internship in a Massachusetts hospital, there came an opportunity to practice medicine, with a small amount of teaching of anatomy on the side, later changed to full-time teaching, at the State University of lowa's Medical School. Here for seven years I had what was perhaps the finest opportunity in the country to get a thorough preparation as a teacher of anatomy. This was under Dr. Henry J. Prentiss, a phenomenal teacher and anatomist and also an exacting and somewhat difficult chief. It is an interesting and long story, I think, but it cannot be told here. To my complete surprise I was asked in 1911 to return to my old school to take over the Department of Anatomy. Here at last was my own chance to develop as best I could the teaching of anatomy along the lines I desired, unhampered and, as it happened, entirely unassisted - at the outset.

The new work was absorbing, for not only did I have to teach, as it turned out during my first year, 39 hours a week, but I had to teach besides gross anatomy and histology (class and laboratory for each) a course entirely new to me as teacher, surgical anatomy, in which I had to make dissection demonstrations on the cadaver before the class. And in addition to this three-ring affair, I was my own technician in both histology and anatomy. I had to prepare the anatomical material myself, no small job, to make slides for microscopic work, and shortly I had to take over another course, new to me as teacher, neuro-anatomy. For those first two years, most of all, I lived day and night at the school so that at the end of each semester I think my wife thought she needed an introduction to her husband.

Though I thoroughly liked the work and the opportunity given me of building my own department, it was impossible to carry on at that pace for more than a short time. In 1913 I was allowed the first of my many assistants. Among these was a young man who had taken two years of medicine at Dartmouth, then had left to earn money by school-teaching before he could continue his medical studies. In his first years as instructor he worked skillfully and incessantly to create a large and comprehensive backlog of histological slides towards the many thousands later forming the slide-library of the department. Later he was able to complete his medical education, not then offered at his alma mater, for he was a member of the first class to finish its second year after the College ceased to give the medical degree. Soon he became internist in the original group that formed the Hitchcock Clinic. Dr. Harry T. French is now retired from faculty and clinic after 44 years of teaching in the Department of Anatomy, after having served the longest term of any member of the anatomical staff since the beginning in 1797. I have deep affection and high regard for Dr. French, with whom I have long been closely associated, for the vital help he gave as a member of the Department of Anatomy and for his knowledge, skill, and integrity in the practice of his profession.

Dr. Syvertsen came as a full-time assistant in 1923, later becoming Secretary and then Dean, serving in these positions and as teacher with a faithfulness beyoud words until his tragic death in January 1960. Traditions concerning him as teacher and administrator for 37 years have been handed down to you, I am sure.

COMING here in 1911, looking for great things, I was little prepared for what happened. It was at this time the shadow which had threatened us for some years stood directly over the School, and the question was flatly before us: "Should Dartmouth Medical School attempt to continue as a four-year school under the attending circumstances?" The question was answered for reasons you all know by reducing the school, "as a temporary measure," to a two-year school, which it has continued to be from 1914 until this day. It is not my intention nor is it now in my province to discuss this step at this time. The decision introduced many difficulties and problems, among which was the transference of our two-year students to full-fledged medical schools. Let me say here that this has been consistently done ever since that date and most satisfactorily to the medical schools to which our students were assigned. For most of his service as an administrator Dr. Syvertsen was the agent through whose unflagging industry, interest and ability this was accomplished - and not always was it a simple matter.

Among the changes that have affected the school none has affected it more profoundly and advantageously than has the coming of the Hitchcock Clinic. This came under the skillful and energetic leadership of the wise and far-seeing Dr. John P. Bowler - who continued and greatly expanded the earlier work of Mr. Hiram Hitchcock. It is not the time to discuss this well-known institution beyond saying that its existence has meant an extended instruction to its students, an added stimulus to its faculty, as well as a general increase in the quality of medical care given everyone in this community. In my department it has brought invaluable aid in the special knowledge and skill of a continuing stream of part-time instructors.

Through my classes at Dartmouth Medical School have passed over six hundred students, of whom a large part are living today and in the practice of medicine. It includes a good many men whose names are written high on the roster of success and among these are a lot of able, hard-working and useful practitioners of all specialties, of whom Dartmouth can well be proud. Several Negroes have been in these classes, almost invariably first-class scholars, one leading his class, all men for whom I am proud to have been teacher; we have had many football players who will be found to average well among the group; Hanover boys, sons of faculty men of the academic and medical persuasion, and of personal friends; and, later, sons of my earlier students, though, alas, I have never taught their grandsons. Three of my students helped start the Hitchcock Clinic, out of the five founders, and since then many others have become its members, some of them teaching in the Anatomy Department today. There are many stories I could tell about these men, but probably not as many as they might divulge about me. I have enjoyed my almost fifty years of teaching (most of it in Dartmouth Medical School) immensely and think I was among the most fortunate of men in having my position in this school made still more satisfying from the fact that my direct ancestors and I have studied, taught or administered their responsibilities at Dartmouth for 125 years. . . .

Well, how about anatomy after all these years? I love it more today than in the beginning. I feel it still belongs in the curriculum, though physiologists, and perhaps chemists, biochemists, pathologists and microbiologists may feel that its hours were needed for really important subjects. Also it is my strong feeling that it is still true that a tinkerer can't know too much about whatever he tinkers with. He who deals with a machine, as the doctor deals with the human body, should understand its structure. Too, he must understand its structure under abnormal conditions, when functions, too, become abnormal along with the changes in structure, and in this way he best knows the possibilities for improving or offsetting the abnormal structure or function. This, it seems to me, is a large part of the job of the medical student. So, I still think anatomy is a necessary evil, and that anatomists therefore will continue to exist. Long life to them, every one!

My years of teaching came to an end about fifteen years ago but not my concern for Dartmouth Medical School. It was apparent then that the school was reaching the point where another change was necessary, as vital as that effected under the wise counsel of Dr. C. P. Frost and again later when the last two years of the course were amputated — to say nothing of more gradual adjustments made from time to time.

Today you, the first two classes under the new regime and others equally interested, are sitting here in a new building, just completed, magnificently equipped and provided for its purposes. You are shepherded by a group of mostly new and competent teachers under the watchful eye of a wise and forward-looking dean, backed by a history of 164 years of growth, carried on by a succession of doctors, many of whom were as competent and enterprising for their times as we find here today. I might say - "like fathers, like sons." "Look to the rock from which you were hewn and to the quarry from which you were digged."

I hope it is plain why my talk concerns the past as a lively part of what has been - the Very Old and the Old. The New is yours. May it equal and better the record of the Old - for you are the NEW.

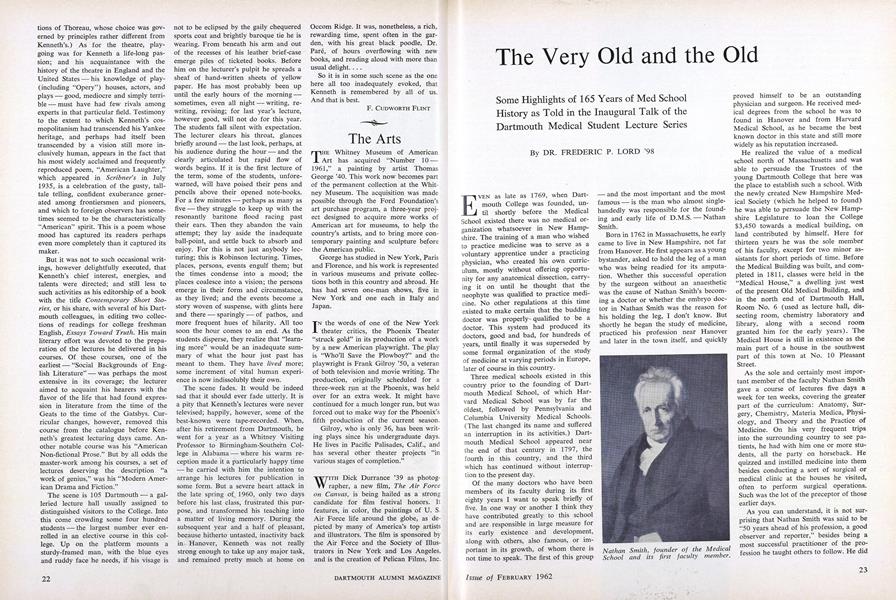

Nathan Smith, founder of the MedicalSchool and its first faculty member.

Dr. Reuben D. Mussey

Prof. Oliver Wendell Holmes

Dr. Dixi Crosby

AUTHOR: Dr. Frederic P. Lord '98 (center) with the late Dean Rolf Syvertsen '18 and the late Dr. John F. Gile '16 at the 150th anniversary observance of the Medical School. Dr. Lord, great-grandson of President Nathan Lord of Dartmouth and son of Prof. John K. Lord '68, was Professor of Anatomy from 1911 to 1946 when he retired and assumed emeritus rank.

Dartmouth medical students in the Classes of 1887 and 1888 pose in front of theoriginal "Medical College" Building, which was used until very recent years.

The Medical School class of 1934, complete with mascot.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStage Director at the Met

February 1962 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureKenneth Allan Robinson

February 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Feature

FeatureELEAZAR WHEELOCKS, IN DIRECT LINE, STILL LIVE – IN TEXAS

February 1962 By SEYMOUR E. WHEELOCK '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1962 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1962 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON, JAMES B. GODFREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

February 1962 By CHARLES F. McGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY, H. SHERIDAN BAKETEL JR.

DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98

Features

-

Feature

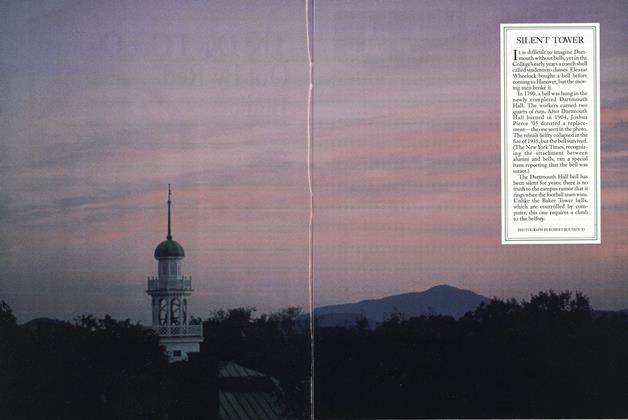

FeatureSILENT TOWER

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

DECEMBER 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOCK-DUEL MURDER

April 1956 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

Novembr 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

Featurenotebook

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By LAURA DECAPUA PHOTOGRAPHY/TUCK -

Cover Story

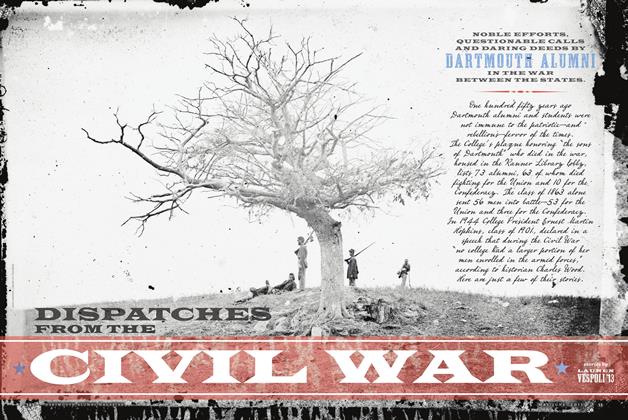

Cover StoryDispatches from the Civil War

May/June 2013 By LAUREN VESPOLI ’13