In Memoriam

WHEN on December 20, 1961, Kenneth Allan Robinson, Professor Emeritus of English in Dartmouth College, died, far more came to its earthly close than a career of honorable service to the College - distinguished though that service was. For with Kenneth Robinson's death there has gone from among us one of those completely individualized, uniquely dedic ated, and durably memorable figures who - never numerous - become the legendary heroes of whatever enterprises they take in hand. For they do not assemble a role from the expectations or standards of others. They themselves crea te the atmosphere by the light and color of which they are perceived; we do not so much judge them as judge ourselves by them; if several of them are contemporaries, later memory looks back on their age as Golden for the community fortunate enough to have known them.

From his place of birth - Kenneth was born in Biddeford, Maine, August 10, 1891, where his father, John W. Robinson, was editor of the Biddeford Record; from his choice of Almae Matres - Kenneth gained his A.B. at Bowdoin College in 1914 and his A.M. at Harvard in 1916; from his long active service on the Dartmouth faculty - from February, 1916 until his retirement in June 1959; from his choice of a Hanover wife - Jean Lambuth, herself daughter of one of the memorable patriarchs of Dartmouth's Department of English from all this, one might conclude that Kenneth would be a Yankee of the Yankees. And Yankee traits he did have: a humor always kindly, often concise, and relying for its effect on the flatting rather than the sharping of the expected note; a tolerant sanity, which rather expects to find foibles in one's neighbors, but finds them all the more natural for that; and perhaps some shyness in personal relationships.

But if Yankee Kenneth was by birthright, Puritan he was not. There are those who would praise their Maker by renouncing his gifts - at least, those that are visible; there are those whose instincts teach them to praise their Maker by enjoying his gifts. Of this latter company was Kenneth Robinson. And not only those gifts that are visible; those also that are audible, tangible, even edible. For Kenneth loved the panorama of life; he loved to be among men and women congregated. Perhaps mutely but none the less intensely, he shared in the kinetic ambience of the boulevard, the cafe, the theatre.

Like some other people reticent about their thoughts of the immediate moment, Kenneth was not only sympathetically and amusedly perceptive of what was taking place around him, but moved to set forth this awareness for the benefit of others, once his impressions had been winnowed and shaped by his taste. His charming social verse, published in Life,Scribner's, the New Yorker; and, often in some publication sponsored by the College, his evocative prose, pitched midway between the nostalgic and the humorous, testify to his humane epicureanism. He knew intimately his Manhattan; his Paris he adored, the "silvery city" with its "street that goes singing to the tall arch gray on the sky." He was even a perpetually returning client of one favorite restaurant there, Le Medicis - something of an accolade for the establishment; for Kenneth was possessor of a choice collection of livres de cuisine. (But his gastronomic opinions were not fanatical; in Thoreau and the Wild Appetite, an essay appearing in 1957 under the joint sponsorship of the Thoreau Society and the Friends of the Dartmouth Library, Kenneth wrote most ingratiatingly of the alimentary recommendations of Thoreau, whose choice was governed by principles rather different from Kenneth's.) As for the theatre, play-going was for Kenneth a life-long passion; and his acquaintance with the history of the theatre in England and the United States - his knowledge of play-(including "Opery") houses, actors, and plays - good, mediocre and simply terrible - must have had few rivals among experts in that particular field. Testimony to the extent to which Kenneth's cosmopolitanism had transcended his Yankee heritage, and perhaps had itself been transcended by a vision still more inclusively human, appears in the fact that his most widely acclaimed and frequently reproduced poem, "American Laughter," which appeared in Scribner's in July 1935, is a celebration of the gusty, talltale telling, confident exuberance generated among frontiersmen and pioneers, and which to foreign observers has sometimes seemed to be the characteristically "American" spirit. This is a poem whose mood has captured its readers perhaps even more completely than it captured its maker.

But it was not to such occasional writings, however delightfully executed, that Kenneth's chief interest, energies, and talents were directed; and still less to such activities as his editorship of a book with the title Contemporary Short Stories, or his share, with several of his Dartmouth colleagues, in editing two collections of readings for college freshman English, Essays Toward Truth. His main literary effort was devoted to the preparation of the lectures he delivered in his courses. Of these courses, one of the earliest - "Social Backgrounds of English Literature" - was perhaps the most extensive in its coverage; the lecturer aimed to acquaint his hearers with the flavor of the life that had found expression in literature from the time of the Geats to the time of the Gatsbys. Curricular changes, however, removed this course from the catalogue before Kenneth's greatest lecturing days came. Another notable course was his "American Non-fictional Prose." But by all odds the master-work among his courses, a set of lectures deserving the description "a work of genius," was his "Modern American Drama and Fiction."

The scene is 105 Dartmouth — a galleried lecture hall usually assigned to distinguished visitors to the College. Into this come crowding some four hundred students - the largest number ever enrolled in an elective course in this college. Up on the platform mounts a sturdy-framed man, with the blue eyes and ruddy face he needs, if his visage is not to be eclipsed by the gaily chequered sports coat and brightly baroque tie he is wearing. From beneath his arm and out of the recesses of his leather brief-case emerge piles of ticketed books. Before him on the lecturer's pulpit he spreads a sheaf of hand-written sheets of yellow paper. He has most probably been up until the early hours of the morning — sometimes, even all night - writing, rewriting, revising; for last year's lecture, however good, will not do for this year. The students fall silent with expectation. The lecturer clears his throat, glances briefly around - the last look, perhaps, at his audience during the hour - and the clearly articulated but rapid flow of words begins. If it is the first lecture of the term, some of the students, unforewarned, will have poised their pens and pencils above their opened note-books. For a few minutes - perhaps as many as five - they struggle to keep up with the resonantly baritone flood racing past their ears. Then they abandon the vain attempt; they lay aside the inadequate ball-point, and settle back to absorb and enjoy. For this is not just anybody lecturing; this is Robinson lecturing. Times, places, persons, events engulf them; but the times condense into a mood; the places coalesce into a vision; the persons emerge in their form and circumstance, as they lived; and the events become a story woven of suspense, with glints here and there - sparingly - of pathos, and more frequent hues of hilarity. All too soon the hour comes to an end. As the students disperse, they realize that "learning more" would be an inadequate summary of what the hour just past has meant to them. They have lived more; some increment of vital human experience is now indissolubly their own.

The scene fades. It would be indeed sad that it should ever fade utterly. It is a pity that Kenneth's lectures were never televised; happily, however, some of the best-known were tape-recorded. When, after his retirement from Dartmouth, he went for a year as a Whitney Visiting Professor to Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama - where his warm reception made it a particularly happy time - he carried with him the intention to arrange his lectures for publication in some form. But a severe heart attack in the late spring of 1960, only two days before his last class, frustrated this purpose, and transformed his teaching into a matter of living memory. During the subsequent year and a half of pleasant, because hitherto untasted, inactivity back in Hanover, Kenneth was not really strong enough to take up any major task, and remained pretty much at home on Occom Ridge. It was, nonetheless, a rich, rewarding time, spent often in the garden, with his great black poodle, Dr. Pare, of hours overflowing with new-books, and reading aloud with more than usual delight. . . .

So it is in some such scene as the one here all too inadequately evoked, that Kenneth is remembered by all of us. And that is best.

Prof. Kenneth Allan Robinson, A.M. '23

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Very Old and the Old

February 1962 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Feature

FeatureStage Director at the Met

February 1962 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Feature

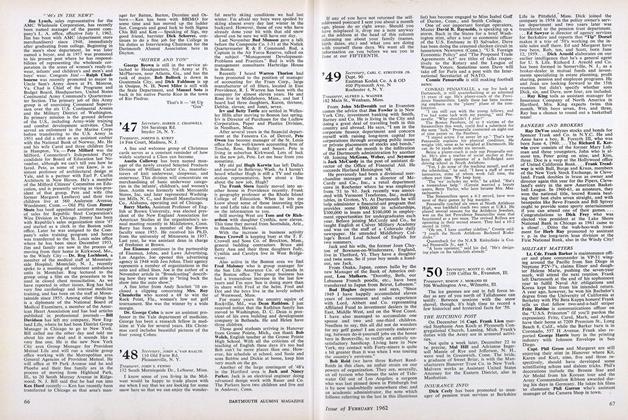

FeatureELEAZAR WHEELOCKS, IN DIRECT LINE, STILL LIVE – IN TEXAS

February 1962 By SEYMOUR E. WHEELOCK '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1962 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1962 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON, JAMES B. GODFREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

February 1962 By CHARLES F. McGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY, H. SHERIDAN BAKETEL JR.

F. CUDWORTH FLINT

-

Books

BooksSADDLING PEGASUS

JANUARY 1932 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksBEAU-POIL AU MAROC

June 1940 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksSPARROW HAWKS

October 1950 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksTHE MODERN CRITICAL SPECTRUM.

DECEMBER 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksTHE WORLD, THE WORLDLESS.

JUNE 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksTHE GEORGIAN REVOLT: RISE AND FALL OF A POETIC IDEAL, 1910-1922.

NOVEMBER 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StorySteve Slanec '87

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureThree in the Theater

APRIL 1971 By BARBARA BLOUGH -

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38 -

Feature

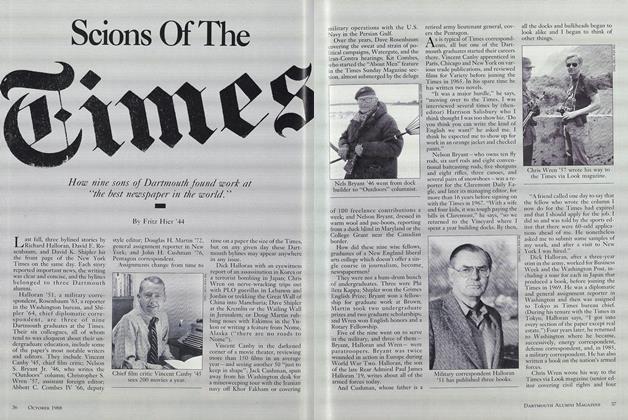

FeatureScions Of The Times

OCTOBER 1988 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

JULY 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

FEBRUARY 1969 By Susan Liddicoat