By G. J. Goldberg. Hanover: Atelier 21, 1962.64 PP.$5.50.

Diaspora: 1. the dispersion of the Jews after the Babylonian exile. 2. the Jews thus dispersed.

As their title suggests, these are Jewish stories and their heroes (Munya Gitlin, Mitka Fibelman) are far removed from any conceivable Promised Land. By the waters of various Babylons they sit down and weep, and make perfect fools of themselves while doing so. In their irony, their verbal brilliance, their self-deprecation, above all in their ability to see life as simultaneously terrible and ludicrous, these stories are as Jewish as their heroes. And yet, the Diaspora they describe is not - or is not simply— that of Jews in an alien, Gentile world. To be sure, Mitka. Fibelman, being interviewed for a job in the Ivy League, is forced into the tormenting admission that when he says he comes from "near Westchester," he means he lives in the Bronx. But what of Munya Gitlin? His is a Diaspora within Diaspora. He gets a job in a school so Jewish that (except for Munya) everyone, even the Negro elevator operator, wears a yarmulka - a skull cap. And what happens? The second day he is locked out of his classroom, and we leave him as he tries in vain to overhear what people are whispering about him in the Principal's office.

In fact, the Diaspora of which these heroes are a part is the one of which we are all a part, and the Promised Land from which they are excluded is the one we are all looking for. We have been told it is within us, but in most cases that doesn't seem to help. Meanwhile, in our discontent with Babylon, we are absurd. That absurdity, Mr. Goldberg seems to say, is the sign of our humanity. In the finest of these stories, Mandelbaum the painter, widowed, childless, entirely alone, rejects the panting, sinister humanitarianism of one Mordecai Koussevitsky, and rejects the attractive lady who wants to share his table and comfort him with warm milk. When, however, Mandelbaum sees a grotesque, robot-like clown, he realizes suddenly that he is in the presence of another human being - and he runs away.

These are wry, funny, ironic stories, as precise and meaningful in their absurdity as dreams. They are presented, what is more, in a format of unusual handsomeness. Binding, type, and paper have been well chosen, and each volume contains four black and white abstract drawings by Nancy Marmer, the author's wife - drawings which, as works of art, equal the stories they complement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

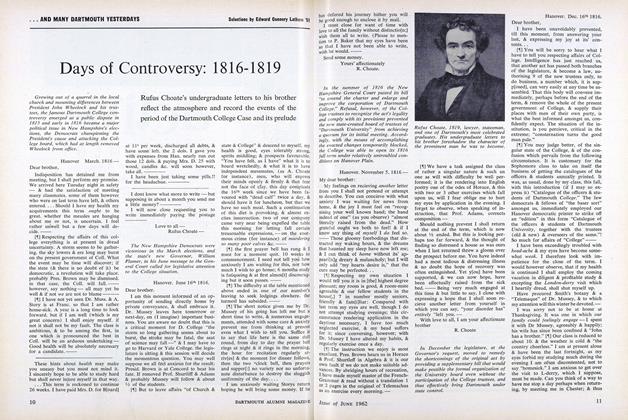

FeatureDays of Controversy: 1816-1819

June 1962 -

Feature

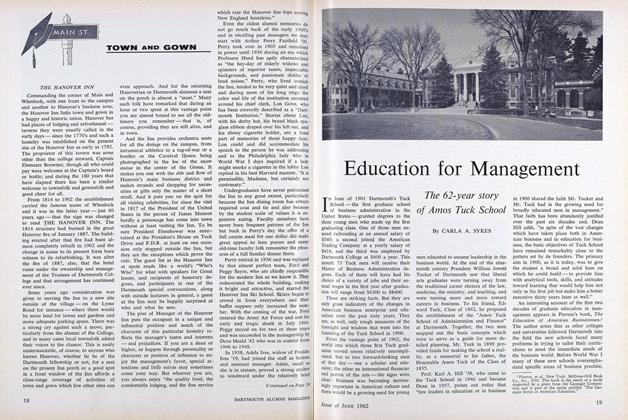

FeatureEducation for Management

June 1962 By CARLA A. SYKES -

Feature

FeatureA College-Church Partnership

June 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

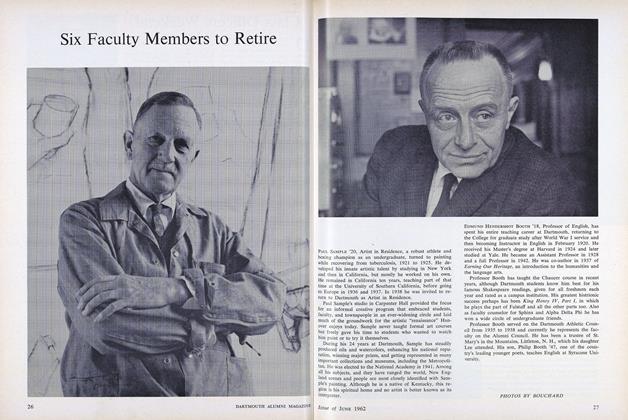

FeatureSix Faculty Members to Retire

June 1962 -

Feature

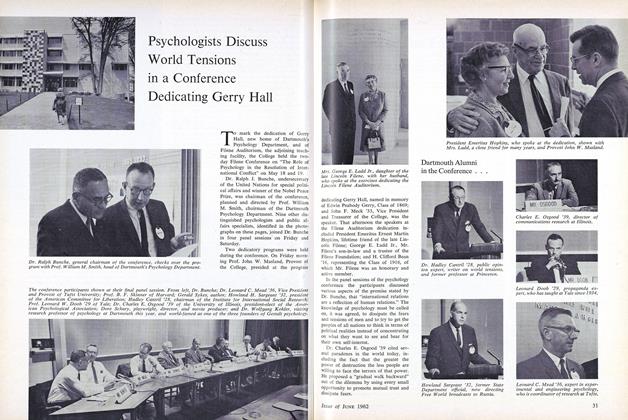

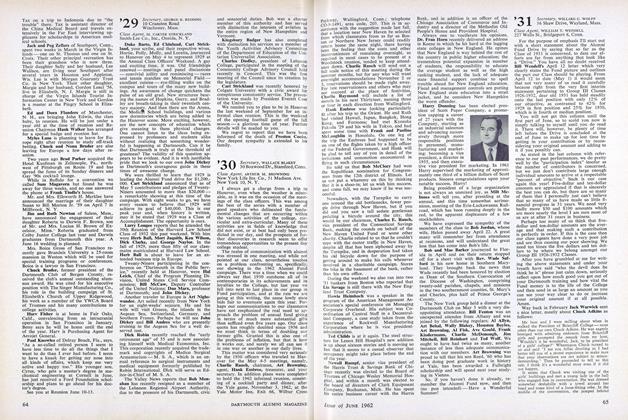

FeaturePsychologists Discuss World Tensions in a Conference Dedicating Gerry Hall

June 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1962 By WILLARD C.WOLFF, WILLIAM T. WENDELL

ROBERT G. HUNTER

Books

-

Books

Books"Wholesome Marriage"

NOVEMBER 1927 -

Books

BooksThe Crow's Nest

March 1935 -

Books

BooksHIS EXCELLENCY, GEORGE CLINTON, CRITIC OF THE CONSTITUTION

May 1938 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksTHREAD OF SCARLET

May 1939 By E. P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksHMS CEPHALONIA.

OCTOBER 1969 By VINCENT E. STARZINGER -

Books

BooksSAIL IT FLAT: THE SUNFISH RACING PRIMER.

MAY 1972 By WILLIAM J. HURST