EPHESIANS 11, 17-19.

Two years ago, on March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed Executive Order 10924, creating the Peace Corps, a volunteer organization that caught the hearts and imaginations of young people on college campuses across the nation.

Any valid judgment of the Peace Corps must await time and the verdict of historians, but after two .brief years of existence over 5,000 PCVs - Peace Corps Volunteers (3,170 men and 1,839 women) - are creating their own history as teachers, technicians, community developers, and goodwill ambassadors in 45 nations scattered throughout Africa, the Far East, Latin America, the Near East, and South Asia.

These young people (the average age is 23) live and work, usually for two years, in locations which were for them only places on the map, or in some cases, countries too new for the map. In this volunteer group are twenty-nine Dartmouth men, half of them from the Class of 1960 and younger, serving in seventeen different countries (see map). As Sargent Shriver, Peace Corps Director, points out in his telegram, Dartmouth leads the Ivy League institutions in percentage of men participating in the Peace Corps. The College holds up very well also in terms of actual numbers, ranking ahead of Brown and Princeton, which have fourteen and nineteen PCVs respectively; and close to Yale, 42; Pennsylvania, 49; and Cornell with 52. Harvard with 70 and Columbia with 72 are highest.

The Big Green PCV contingent is literally spread "around the girdled earth" with the largest group of four men - John G. Coe '62, William P. Hart '36, Robert L. Savage '62 and Paul E. Tsongas '62 - serving in Ethiopia. Charles F. "Doc" Dey '52, on a leave of absence from his duties in the Dean's office at the College, heads the Philippines group which includes Parker W. Borg '61 and Richard H. Rodefer '60. Thailand also has three Dartmouth representatives Arthur Schweich '53, Louis J. Setti '62, and Sumner M. Sharpe '58.

Two Dartmouth men are serving in each of these nations: Colombia - Henry Hof III '58 and Fred Z. Jaspersen '61; Tunisia - Ross M. Burkhardt '62 and John F. Murphy '5B; Nepal - Peter Farquhar '6O and Ralph S. Hambrick Jr. '63; Pakistan - Robert G. McGuire '58 and Gene F. White '56; Morocco - Curtis M. Comstock '64 and Lewis H. Nash '54; and Nigeria - Don S. Samuelson '62 and Benjamin Vogel '62.

The College has one representative in each of the following nations: Jamaica - Sam K. Bryan '61; Peru — D. Scott Palmer '59; Sarawak - Frank B. Sherman Jr. '57; Venezuela - Jonathan F. Seely '57; Sierra Leone - William C. Whitten Jr. '62; Dominican Republic - Nathan B. Witham '60; and Ghana - William M. Woodhouse '59.

In an important post at Peace Corps headquarters in Washington, D.C., Robert B. Binswanger '52 is serving as a training officer.

From the very start the Peace Corps concept was accepted enthusiastically, both at home and abroad. Through sound planning, training and organization, plus a strong public relations program, the Corps has been remarkably effective in its goodwill mission. Except for the famous "postcard incident," the letters home to parents and friends from PCVs have been unusually good. More importantly, the "round robin newsletters" from overseas (once a ditto machine has arrived) give the hometown press and radio some unusually thoughtful and mature reports on programs of the Corps plus a real insight into local affairs and conditions in these remote areas of our world.

Interest in the Peace Corps among today's undergraduates, at Dartmouth and elsewhere, is high, as it must be, for the Corps is now seeking some 4,000 additional volunteers, largely to serve as replacements for the original volunteers who start leaving their posts this summer. Furthermore, as the solid achievement of the Peace Corps program has spread across the world the demand by nations for volunteers has tripled, according to Corps officials.

Here in Hanover, Andrew B. Foster '25, a retired Foreign Service Officer and now a special assistant to President Dickey, is serving as the liaison officer between the College and the Peace Corps. Recently Mr. Foster canvassed the Dartmouth men in the Corps seeking their comments, observations and thoughts on the Corps to share with undergraduates interested in the program. The replies included handwritten notes, long letters, typed reports, and mimeographed newsletters, and these were utilized to make up the bulk of this article.

One of the Dartmouth men perhaps best able to assess the contribution being made by the Corps is Bob Binswanger '52, who since its inception has served as a training officer, working out of the Washington headquarters. Binswanger, who is primarily responsible for the training programs for teachers and project PCVs going to some fifteen African states, writes:

"The Peace Corps, as seen from Washington, is a new departure from static foreign policy concepts that has won over its greatest doubters in less than two years. It remains a concept that presents the true image of America abroad as never before possible, and brings to the underdeveloped nations of the world that unique commodity - American initiative, imagination, energy and spirit, complemented by a respect for human kind and individual dignity, always inherent in our society but rarely seen by persons foreign to our culture. ... I believe this is a bipartisan ideal, eagerly grasped by citizens of every variety who have been waiting for something other than war in which to serve their country while serving the greater cause of peace."

Although volunteers are strongly urged to stay away from political discussions and from trying to convert people to the ways of democracy, there is little doubt that a thoughtful, mature Peace Corps representative can have a profound influence. in remote nations. Witness this letter from Scott Palmer '59, former star end on the Dartmouth football team and captain of the Dartmouth Rowing Club. Scott is teaching English at the 500-student National University of San Christobal de Huamaga, located at the provincial capital of Ayacucho, Peru:

"President Kennedy's Cuban speech and subsequent U.S. actions made a tremendous impact on some sectors of the University. Deep running political currents, hitherto unobserved, burst to the surface. On Tuesday night a large number of students marched through the streets to the cries of 'Cuba, si, yanquis, no' and 'Cuerpe de Paz, cuerpo de Guerra,' (Peace Corps, War Corps). Three different student political organizations printed leaflets during the week condemning the U.S. blockade of Cuba."

In spite of the high anti-American emotions stirred up by the Cuban episode, Palmer reports that "classes functioned normally all week," and then goes on to explain how he and the other PCVs responded to the many pointed questions raised by Peruvian students:

"In our replies we tried to explain the various factors which shaped the firm stand taken against Cuba and Russia. . .. We also tried to make it clear that American policy toward Cuba is based on a special set of circumstances which differentiates it markedly from policy with regard to the rest of Latin America. The Cuban crisis also made it necessary to explain very carefully the objectives of the Peace Corps in general as well as the presence of six volunteers in Ayacucho. ... We tried to make it clear that we have specific jobs to do at the University; that we have not come to spy, to engage in politics, to serve as a microphone for U.S. propaganda. We are not trying to convert anyone to our various outlooks, but we did try to present to our questioners a somewhat different perspective on the crisis to help them form their own conclusions."

A special House Foreign Affairs Study Group has just issued a report citing the Peace Corps for "boosting the U.S. to the crest of a new popularity wave in South America." The report said in part: "We were deeply impressed by the warmth with which the volunteers are regarded by the Latin American people with whom they live and work. We were also impressed by the manner in which the volunteers have adjusted to rugged and often primitive living conditions. The American people can be justly proud of these men and women who are carrying on our best traditions of humanity with an indomitable frontier spirit."

Henry Hof '58 admits that working on community development in Bogota, Colombia is considerably different from his former post as a real estate administrator in Wall Street, New York. Yet for Hof each day brings the new and unexpected challenges he welcomes. One day, with the president and vice president of the local community junta, he went calling on the director of the U.S. Atoms in Action exhibition to see if the new building (or any part of it), housing the exhibition, could be turned over for local use when the exhibition left. Unfortunately, the building was portable and moved with the exhibits, but Hof managed to get the cement foundation and then obtained help to cut it apart and place it over an open drainage-sewage ditch which had been both an eyesore and health hazard to the community for many years. At the meeting with U.S. officials, Hof remained largely silent. "I hoped to force, by my silence, the President to do most of the talking," Hof explained. "Our Peace Corps mission is to encourage the people to help themselves. Thus, when our team of three volunteers leave Galen, in July of 1964, we hope that the community will be capable and enthusiastic enough to continue the development of their community on their own."

Hof also teaches English one hour a day at a local school to a group of "fifteen-year-old senoritas," and he adds, "it's a real pleaure!" However, the "Plaza de torres" flop, as Hof termed it, soon proved that life was not always pleasant. A local entrepreneur inveigled Hof into helping him promote a bull fight, with funds going to pave the local streets. The bullfight failed (the bulls even had to be prodded out of the trucks into the arena). They tried again - this time by showing a movie (borrowed from the U.S. Information Service) and charging admission. "Lopez (the entrepreneur) had collected the money," Hof relates, "and after everyone was seated we found out that there was just not enough electrical current to present both the picture and the sound. We tried showing just the picture - but it was silly. Soon the crowd began to mumble, grumble and utter things I fortunately did not understand. Little by little they left, very unhappily - and then, to make things worse, all our lights failed. In the dark I felt a sting on my hand, another on my back and realized things were being thrown. As we left, a friend - a Colombian with a knife - dispersed a bunch of kids, saying 'they were waiting for you!' I went home with a headache, a bloody hand and a deep sense of failure."

But Hof is not dismayed. "This was the only failure in three months," he tells us, and a page later he excitedly reports: "This week, for instance, I plan to find an open lot and set up a projector and after dark show a movie. As the word gets around, there will probably be two hundred or three hundred happy spectators. A fun evening for all."

Jon Seely '57 is also working in Latin America, teaching English at a new university - Universidad de Oriente, located in Ciudad Bolivar, Venezuela. He writes: "I, with one Peace Corps colleague, have been teaching English to approximately 80 students in the schools of medicine and mining, which have just completed their first year of classes. ... Actually only a small percent of our time is spent in the classroom with these students, for in addition we have been preparing a language laboratory and collecting and cataloguing books for the library. We have also launched a large program of night classes for townspeople. Furthermore, we are entering the 'liceos,' or high schools, with English classes and programs designed to attract the interest of these students; we have called them 'English Clubs.' In January we will be teaching in a vocational school. ... Much of our time is spent in unofficial public relations work both for the university and in our own behalf. Our home has been turned into a kind of student union, where we have formed an important Off-campus contact which is unusual among student-faculty relationships here. And who has been asked to feed bananas to the University's monkey? Why the Peace Corps, of course!"

Working as a Peace Corps physical education instructor in a Bourguiba Youth Village at Zaghouan, Tunisia, is Ross Burkhardt '62. Ross and his colleague Kurt Liske of Kent, Ohio have charge of a group of about sixty youngsters ranging in age from ten through seventeen. "A typical class consists of ten minutes of running and walking exercises, fifteen minutes of calisthenics, and half an hour for the lesson." Ross writes. "We now spend three hours a week in coaching volleyball, handball and cross-country. It seems that while we teach efficiency to the Tunisians, they teach us patience! Of course, the most important detail of my work is the following chant - ouehed, thrine, thlethe,arba (Arabic for one, two, three, four)."

American officials help make Peace Corps life interesting, however, as Burkhardt reports: "Thanksgiving day, 1962, is one for the books. The new Ambassador, Francis H. Russell, invited six PCVs to dinner. He is extremely interested in the Corps and was in Accra when we came off the plane singing the Ghana national anthem. Kurt and I arrived with the others at his official residence early in the afternoon. Ambassador Russell escorted us on a trip through old Carthage to see the Roman ruins, a reflection of his interest in archeology. Then came the sumptuous meal - a huge turkey, mashed potatoes, creamed onions, cranberry sauce, cider, and to top it all off, pumpkin pie. How many of you were feeling sorry for us and our hard life on November 27?"

Burkhardt makes one request - "If any of you know a high school boy or girl who would like a Tunisian pen-pal, please let me know. One requirement: a little French, as the boys here do not know English. Write me at Village d'Enfants, Zaghouan, Tunisia."

From Katmandu, Nepal, comes word of Pete Farquhar '60, who teaches geography at both the National High School and a newly created college - Prithwi Narayan College - "a college much like Dartmouth must have been in its first years. Dartmouth was founded for the heathen American Indians, but Prithwi Narayan was founded two years ago by a Christian Indian for the hill tribes of Nepal. PNC is the first and only private, liberal arts college in Nepal; it is the only college in this part of the country; and it is located in the most spectacular wilderness area. The Pokhara Valley is over a week's journey from the nearest road and the only way in or out is by foot or airplane. Machapuchare, a 23-thousand-foot Matterhorn, towers above us ... and the creations of nature are the grandest in the world, but the creations of man are among the most primitive. We have very little except hope. PN College has an enrollment of about one hundred students, mostly boys from outlying villages or the sons of local merchants. The faculty numbers ten, including two PCVs. The college at present consists of a long L-shaped bamboo and thatched hut with dirt floors. There are a few benches for the students and a crude blackboard for the teacher. The library is one cabinet with about seventy books. There is no laboratory equipment, and I have been teaching Geography for two months without even a small world map. Prithwi Narayan is surely a voice crying in the wilderness and with the same double meaning!"

To prospective PCVs, Farquhar offers this observation: "Have no delusion; what the individual volunteer will actually accomplish will be very small indeed. The task is so great that the work of one person will hardly be noticed. One must have the patience of Job and a good sense of humor, for the job is exasperatingly slow and the troubles are numerous. For- tunately even the most trying of days has its rewards."

Another word of advice comes from Frank Sherman '57, working in Kuching, Sarawak: "I have just returned from a conference in Jesselton," he writes, "where my attitude towards the Peace Corps was sharpened by conversations with the sixty-odd volunteers in North Borneo and Sarawak. ... I should like to warn students not to become captivated by the Peace Corps jungle image. While most volunteers are in rural areas, many find themselves in capital cities and other large urban areas. Teaching school in Jesselton, Kuching, etc. with their 'rapid transit' bus systems, crowded streets and air-conditioning and fine restaurants is much like similar work in any American city."

Bearing out this observation is a report from Sam Bryan '61, who writes from Spanish Town, Jamaica, where he is teaching English composition and geometry at the Jamaica School for Agriculture and helping out with a visual aids program: "What about visual aids? This was supposed to be the technical skill that I could bring to Jamaica. (Our project is considered one of the Peace Corps' most technical. We have trained librarians, electricans, plumbers, agriculturalists, vocational and arts and crafts teachers.) I am still on call as a photographer and have recently done more work for the Social Welfare Commission and the Agricultural Society. At the school I am stalf adviser to the camera club (we have a darn good darkroom) and am increasing, mainly, the use of charts and films. We also are using far more films for classroom work than most schools. Too many courses at Dartmouth failed to take advantage of Blair Watson and his Fairbanks Hall, going a full term without a map, chart, slide, or film. We are doing better here, and even old British films on the Hydra, Amoeba, or History of the English Language have value."

And from Thailand comes this observation by Sumner Sharpe '58 who is teaching at the School of Architecture at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok: "The members of the Peace Corps here in Thailand and elsewhere are in many ways a special type of American overseas - working at different skill levels, living on smaller budgets, and living closer to the people of the host countries and to their way of life than most other Americans overseas. ... These Americans have not been sent here nor have they been told to come here; they are not Americans who think that a country far from the United States of America with a strange name is a hardship post; they do not accept special pay as bait to attract them to these 'god-forsaken' places; this is not just another job in another capital of another country in which one must serve to get a promotion. This is simply living and learning as one would anywhere in the world at any time of his life. To use a phrase which is slightly hackneyed, 'this is not a sacrifice.'"

One of the few married men in the Peace Corps is Richard H. Rodefer '60, who with his wife is teaching at Davao City in the Philippines. "My wife and 1 were married before training and after we both had been accepted separately," Rodefer says. "Although early personal adjustment to marriage can be a new experience by itself, we both felt that this venture would be an asset rather than a liability in building the foundation of our new life together.

"Our particular task," he continues, "is the enrichment of the present science and math curriculum at one of eleven pilot high schools. . . . Due to an undersupply of volunteers trained in the physical sciences, only three PCVs are assigned to a particular high school - one in math, biology, and chemistry or physics. Approximately two-thirds of our teaching day is in our specialty with the remaining portion spent in team-teaching general science courses."

Adjustment to local customs and conditions is never easy, Rodefer points out. "Adjustment to a foreign diet is particularly difficult. The first attempt is often less than successful either because of new scents or because the human digestive system requires time to adjust. Furthermore, a PCV is something new and exciting to a native community and the lack of privacy that follows is at times bothersome. ... Finally, the prospective trainee should realize that this type of work, usually in small, isolated villages, is such that little outside intellectual stimulation is available.

"I hope," Rodefer concludes, "that all PCVs of the future can be good catalysts for local and nationwide improvement wherever they are assigned."

Last September Charles F. "Doc" Dey '52, Assistant Dean at Dartmouth, was granted a year's leave of absence to serve with the Peace Corps, and he left with his family to serve as an administrative officer in charge of eighty PCVs in the Philippines. His thoughts on the Corps and its program, as excerpted from a recent letter, are particularly appropriate for concluding this article:

"Eight months ago this morning (April 4, 1963) our 707 touched down at Manila International Airport — four days later the Dey family arrived in Regaspi City, Southern Luzon, where we negotiated a home/office/dormitory/Peace Corps Center arrangement for eighty Volunteers scattered over an area roughly 200 square miles in size. These Volunteers, male and female,, 22 to 30 years of age, arrived October 1961 with the first group of Volunteers to be sent to the Philippines and the third Peace Corps contingent to be dispatched from the States. They suffered the frustrations and hardships expected of 'guinea pigs'; they experienced the excitement and satisfaction of pioneers; they were veterans when we joined them.

"We have come to know them well in these eight months and, with few exceptions, we know them as reasonably bright, energetic, concerned young people - neither Saints nor Supermen, but Americans willing to learn, eager to help and, after eighteen months in the field, properly alert to the opportunities as well as the limitations facing relatively inexperienced A.B. graduates attempting to make a worthwhile contribution in foreign culture. In two months they complete their Peace Corps service. A few will remain in the Philippines for study, research, business or as wives and husbands of Filipinos; most will scatter throughout the Orient, Middle East and Europe prior to returning home. When they depart my wife and I, emotionally and psychologically, will feel that our work is finished and so, we too, shall pack up.

"The Peace Corps attracted us as it inevitably attracts other Americans trying to understand world currents and conflicts; Americans uneasy about their plethora of conveniences and material possessions, Americans sensing that they had much to learn from other cultures, Americans believing that there were many not-so-ugly countrymen who should be communicating with people, ordinary people, around the globe. Further, and of more immediate interest to me, were the ways in which the Peace Corps might relate to liberal education, mine as well as that of Dartmouth students. For two years I had been trying to offer guidance to undergraduates seeking study, work and service opportunities in foreign countries. I lived with the uneasy feeling that without personal association with the non-Western world, poverty, disease, illiteracy, inertia and colonial legacies (how I would change my notes on The Age of Imperialism were I again to teach English History!), I would soon find myself unable to effectively communicate with students who were themselves striving to understand these problems. Sargent Shriver and the Dartmouth Trustees came to my rescue.

"So much has happened so fast in my Peace Corps tour that I am hard pressed to sort out significant events from the purely human interest. There is general agreement among staff members about the need for getting away and digesting all that has transpired. Amidst administrative turmoil and the daily struggle to keep Volunteers usefully employed, there emerges overriding evidence that locating Americans in developing communities throughout the world is a dramatically splendid idea, a concept offering almost unparalleled opportunity for personal growth. A Volunteer is placed in a situation full of unknowns; it is probably the first time in his life when he is almost totally dependent upon himself for ideas, initiative, follow-through and picking up the pieces. He comes to know himself separated from his props twelve thousand miles behind; his tolerance for values and norms that deviate from his own; his patience with vagueness, frustration and facade; his compassion for the abject; his skill in helping others to help themselves.

"Whatever the shortcomings of the mob, almost to a person, all of the eighty Volunteers in this region, knowing what they now know, would again volunteer for service with the Peace Corps. They might choose a smaller program, they might hold out for a more clearly defined role; they would endorse the learning opportunity as simply fantastic. Except for fear of sounding trite, they would acknowledge an ineradicable if not profound change in their most inner being. I fervently hope that upon completion of their Peace Corps service these people will be allowed to return to the usual walks of life quietly, unheralded to cities and towns across the nation, not as returning heroes but as ordinary citizens who have had the good fortune to share an extraordinary experience."

In the concluding paragraph of his letter "Doc" Dey '52 adds a personal statement which might well serve as a guideline for the future aspirations of the Peace Corps and which seems to us to highlight the bright promise which the Peace Corps holds out to American youth and the citizens of the world: "For my part, I have renewed conviction that all of this does make sense, that where intelligently conceived and properly executed, a project can encompass meaningful work for the Liberal Arts graduate; indeed, that the future success of the enterprise depends, in large measure, upon Peace Corps success in attracting broadly educated participants. Beyond this, the major task ahead is the skillful marriage of the best possible human material to honest to goodness jobs."

Robert B. Binswanger '52 (center), training officer for Africa at Peace Corps headquarters in Washington, arriving in Nigeria. With him (l to r) are the EducationMinister, U.S. Ambassador Joseph Palmer, and Dr. Samuel Proctor.

Nate Witham '60 (r) of Newcastle, Maine, and Dale Martin, a Volunteer from Oregon, instructing members of a 4-H club they organized in the Dominican Republic.

Henry Hof '58, assigned to Bogota, Colombia, resorts to mountain climbing inorder to stay trim for community work.

Ross Burkhardt '62 with his students ina youth village in Zaghouan, Tunisia.

Frank Sherman '57, drainage and irrigation consultant for the Department ofPublic Works, Kuching, Sarawak, checksa map made by a Chinese girl assistant.

Charles F. Dey '52 (2nd from rt.), Assistant Dean at Dartmouth, is in charge of 80PCVs in the Philippines. He is shown at the Regaspi Airport with R. Sargent Shriver,Peace Corps director, and members of the Peace Corps staff in the Philippines.

Sam Bryan '61, serving in Spanish Town,Jamaica, teaches English and geometry atthe Jamaica School for Agriculture.

"And came and preached peace to youwhich were afar off, and to them thatwere nigh. ... Now therefore ye are nomore strangers and foreigners, but fellowcitizens..."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureALEMBIC IN LIMBO: A College Dialogue

May 1963 By DAVID McCORD -

Feature

FeatureLewis Dayton Stilwell (1891-1963)

May 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

May 1963 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, WILLIAM T. WENDELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1963 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER DOGS 1963

May 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

Clifford L. Jordan Jr. '45

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

NOVEMBER 1972 -

Books

BooksTHE PATRIOT

January 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureTHE WORLD OF DONALD HYATT

January 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

FEBRUARY 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Books

BooksFIFTY HIKES: WALKS, DAY HIKES, AND BACKPACKING TRIPS IN NEW HAMPSHIRE'S WHITE MOUNTAINS.

JULY 1973 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

APRIL 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45

Features

-

FEATURES

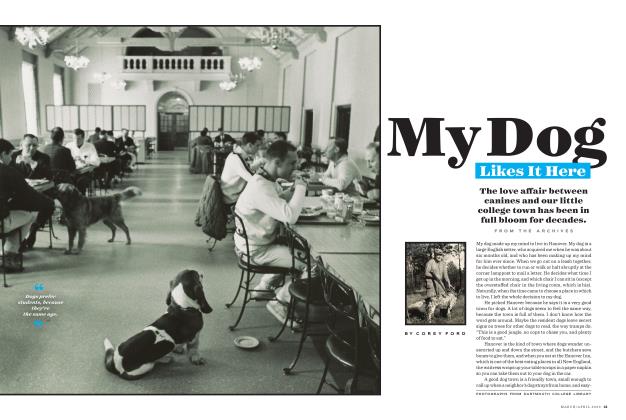

FEATURESMy Dog Likes It Here

MARCH/APRIL 2023 By COREY FORD -

Cover Story

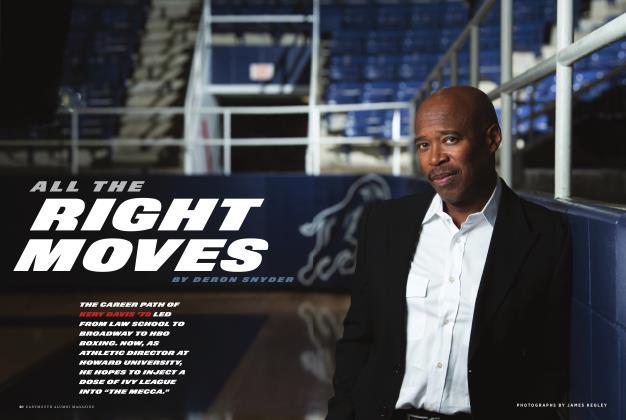

Cover StoryAll the Right Moves

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By DERON SNYDER -

Feature

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

MARCH 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Feature

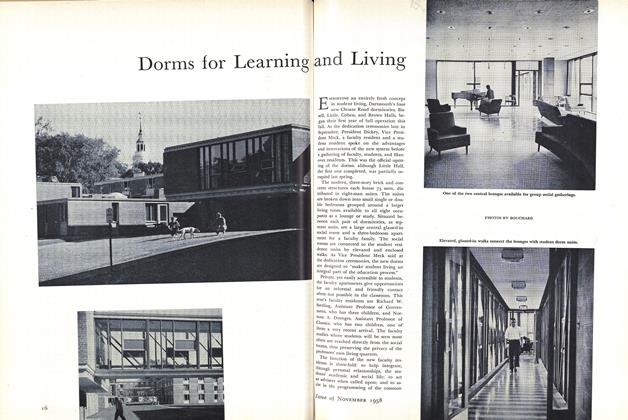

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

By J. B. F. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GREEN UP YOUR KITCHEN

Jan/Feb 2009 By JENNIFER ROBERTS '84 -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84