After a year on the job, is the presidentwhat the College asked for?

The Pedagogue, scene 1: James O. Freedman sits for his portrait as an ex-president of the University of lowa. The pose he has chosen could be taken from a book of Accepted Positions for University Presidents. Freedman's is the one for the teacher: books in background, large head tilted back slightly, right hand lifted, index finger curved in a professional gesture.

The dissipation of support for some of the reforms of the '60s "says something about the degree to which society can absorb the pace of change," he notes. Feminists' use of the court system to bypass reluctant legislatures is a risky strategy, Freedman asserts. He quotes Alexander Hamilton in the Seventy-Eighth Federalist, which states that the Supreme Court "has neither the sword nor the purse." On the other hand, Freedman adds, "the very reason for the Court is to protect the minority."

The two scenes illustrate the essence of Dartmouth's fifteenth president: of all the qualities that the head of a modern university should have fundraiser, teacher, scholar, administrator, mouthpiece, schmoozer the one that most defines James O. Freedman is the pedagogue. The presidency serves as a bully lectern for his teaching; the College is an expanded classroom. His speeches (some of them footnoted in scholarly fashion) quote Whitehead and Holmes. He urges candidates for the White House to read books on education (and offers a reading list). In the dullest Parkhurst meetings his face brightens at the mention of an academic program.

This teacherly characteristic should be kept in mind when one assesses Freedman's first year. However you judge the man's performance, he is, in spades, what the 18-member presidential search committee said it was looking for when it began casting its net in the fall of 1986. The committee listed four basic qualifications for the next Dartmouth president:

• An academic who could get along with faculty and "administer in a collegial manner."

• An articulate national spokesman.

• A teacher who could "stimulate" the intellect of students and "reinforce their moral and ethical values."

• Someone who would "present Dartmouth's case" to alumni while embracing the' College's "special traditions."

These qualifications seem as good a measure as any for Freedman's presidential debut.

FACULTY'S FRIEND: Freedman's standing among those he likes to call his "colleagues" is beyond dispute. The faculty liked him from the start; they loved him after his Dartmouth Review speech on March 28.

NATIONAL SPOKESMAN: Over the past year the president published essays in the New York Times, the L.A. Times and the Chronicle of Higher Education, appeared on network television programs with a combined audience in the millions, met with the editorial staffs of major dailies from Boston to San Francisco, gave the commencement speech at Southern Methodist University and, incidentally, attracted the ire of the far right. (The Wall Street Journal, citing his March 28 speech, called him "the Bull Connor of academia.") "The important thing is that television news producers and education reporters are beginning to think of the president as a source," says Alex Huppe, director of Dartmouth's News Service. "Whenever the subject of education comes up, Freedman is one of the first to come to mind."

MORAL TEACHER: Freedman believes that a college should help develop both the public and private sides of an individual. Dartmouth graduates, he says, should be capable both of public service and of the "reflection and contemplation" that bring self-renewal. His convocation address last fall centered on this subject in essence, the moral development of the student.

Freedman also clearly feels that his verbal barrage against the Dartmouth Review was mandated by ethics. He told the faculty in March: "If the president of Dartmouth does not speak out on momentous issues affecting the College's future, perhaps because of fear of alienating segments of the community or of creating repercussions in the public press, he has abdicated his moral responsibility as the leader of this institution." In fact, he said, a good citizen has a "moral obligation" to criticize the press "upon appropriate occasions."

ALUMNI LIAISON: The president has not exactly ignored the alumni; he has already spoken to them in Cleveland, Chicago, Minneapolis, Denver, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, New York, Washington, Hartford, Manchester, and the Upper Valley. And this doesn't count his speeches to class officers, Alumni Counsellors, and reuning classes.

But if the alumni elected Dartmouth's president every year, this campaign might not end in a landslide. The president's mail from alumni has alternated wildly over the past six months, according to Senior Assistant Ruth LaBombard.

The Dartmouth Review turmoil distracted the community from a series of international developments that seem much more significant to the College's future. In June, 16 Soviet undergraduates came to campus as part of an environmental-studies program that earlier had sent 16 American students to Moscow State University. The program is a direct result of an environmental protection agreement signed by President Reagan and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985.

The Soviet exchange is a step in the continuing internationalization of Dartmouth, bringing to 20 the number of foreign-study programs. Currently, two-thirds of Dartmouth undergraduates spend at least one term abroad in nearly a dozen foreign countries from China to Kenya.

Dartmouth has also expanded its language study to include Arabic and Hebrew, and there are plans afoot for adding Japanese. Japan is already the home of a new program that the Tuck School has established for teaching business, American-style.

International study is one of Freedman's chief interests and a reason for some travel of his own. He is slated to attend a conference of the Internatoinal Association of Universities in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, this month; and he will participate in an international conference on arms control curriculum in Talloires, France, in September.

Another Freedman initiative is to give the student body a more serious intellectual bent. Last spring the College brought to campus 81 high-powered intellects in a major attempt at recruiting. According to Al Quirk '49, dean of admissions and financial aid, about twice as many of the nation's top students will matriculate this fall than have come in past classes. The program caught some controversy nonetheless; presidential scholars are to benefit from special (as yet undefined) programs on campus, a move that critics say creates a superfluous elite on an already elite campus. Students were much less upset about another element of the incoming '92s: women will comprise 44 percent the closest to full coeducation the College has ever come.

What can we expect for the coming year? One of the biggest problems facing President Freedman is "faculty flight." Increasing numbers of top Dartmouth professors are being wooed away by other schools. Seven key faculty members left last year, including two English professors who headed up study in Renaissance literature. In addition, several have taken visiting positions at other schools with the thought of staying permanently. Why the exodus? Professors say rival schools are offering soaring amounts for the best scholars and teachers. The average full professor at Dartmouth earns a comfortable salary in the mid'60s. But Stanford and Duke have offered six figures to some top recruits.

Dartmouth has not been passive about the problem; its faculty now makes a third more than it did five years ago. Yet salaries are also rising rapidly at other schools, and some have reportedly established war chests as bait for the most prestigious scholars. The College also suffers, in some teachers' eyes, from a lack of major graduate programs in the arts and sciences. As a partial solution, Dartmouth has begun a series of Humanities Institutes in which major scholars come to campus for several months and work with the College's faculty. The first such institute, inaugurated this summer, is centered around the study of religious fundamentalism.

A second problem facing the president is what to do with the so-called "north campus" after the Medical Center moves. Dartmouth Medical School, Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital and its associated clinic are slated to occupy a 200-million-dollar complex in Lebanon, New Hampshire, within the next five years. The impending move has triggered a round of planning, assisted by consultants who were hired earlier in the summer. The planners must also consider the growing space needs of the undergraduate sciences and the libraries.

Naturally, money is a major part of any solutions. Look for the announcement of a major capital campaign in the future. Also forthcoming: the possible establishment of a creative writing program at Dartmouth, perhaps modeled after the nationally renowned program at Iowa. And finally, expect the perennial Dartmouth Review land mine. After all, this is still Dartmouth.

The Trustees asked for a teacher and they got him in President James O. Freedman. His boldestfirst-year initiatives have involved quality of learning at Dartmouth. For his lowa portrait byuniversity artist Jerome Witkin, Freedman even struck a pedagogical pose.

Students usually don't get up early, but they set their alarms for regular small-group breakfastswith the president.

One of the president's "heroes" is Robert Coles, a Pulitzer prizewinning child psychologist whogave the Convocation speech last fall.

Jay Heinrichs is the editor of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

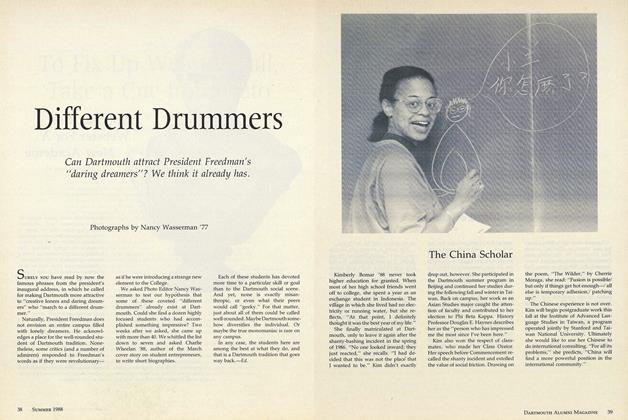

FeatureDifferent Drummers

June 1988 -

Feature

FeatureSUBJECT: HALF OF HUMANITY

June 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement '88

June 1988 -

Feature

FeatureTo Fix Up Webster Hall, Take a Cue from Plato

June 1988 By Brad Denny '63 -

Feature

FeatureNext Month: A (Not Altogether) New Look

June 1988 -

Feature

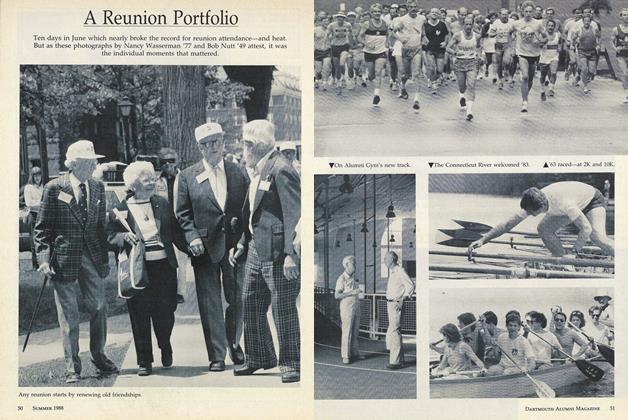

FeatureA Reunion Portfolio

June 1988

Jay Heinrichs

-

Cover Story

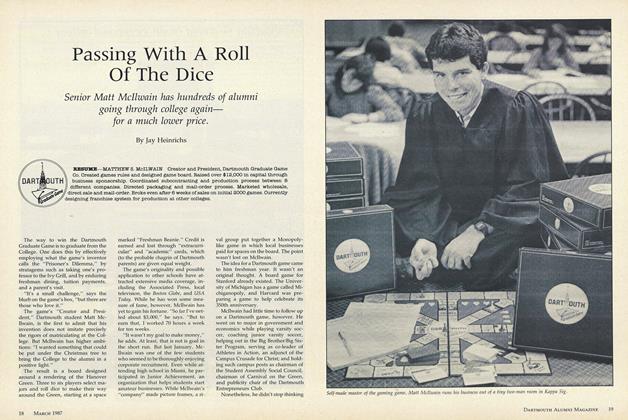

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE THIRD WORLD'S LOW-KEY CRUSADER

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNineties-Version Clubs Have a Heart

NOVEMBER 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNels Comes Home

April 1995 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleStatement of Ownership, Management and Circulation (required by 39 U.S.C. 3685).

December 1995 By JAY HEINRICHS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Alumni Council's 50th Year

JULY 1963 -

Feature

FeatureThe Presidency

April 1975 -

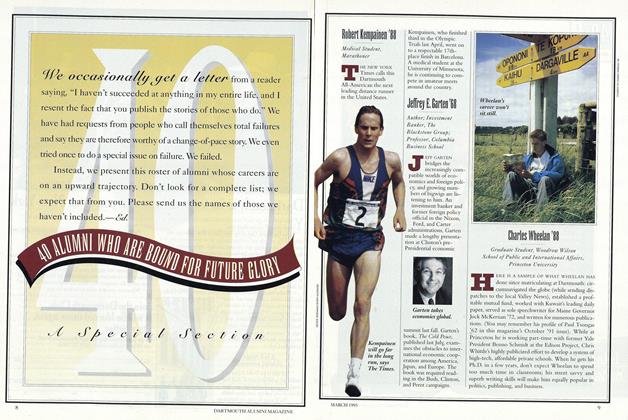

Cover Story

Cover Story40 ALUMNI WHO ARE BOUND FOR FUTURE GLORY

March 1993 -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Natural

MARCH | APRIL 2022 By DAVID HOLAHAN -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62 -

Feature

FeatureMuddling Through Mud Season

APRIL 1978 By Steven L. Calvert