SPRING vacation this year began as usual in the depths of winter. With the snow still deep on the ground, the hegira to warmer or more congenial climates commenced; and by the time exams ended, when the last limp and soiled blue book had been collected, nearly the entire student body had faded into a clangor of suitcases and skis and a roar of motors, and then to empty hallways and unlighted rooms. The dormitories were as bereft as if they had been touched with bubonic plague; New Hamp alone preserved signs of life, for it was open all during the holiday to any undergraduates who wished to remain in Hanover. Some of the fraternities were also operative but, like everything else, they too performed on a drastically reduced scale.

Yet the effect was more than that of something diminished by being abandoned a balance had been upset, an equilibrium disturbingly unsettled. Suddenly, instead of the town taking its sustenance and splendor from the College, the College was an annex of the town; it was, in fact, in its deflated condition, surrounded by its suburbs, pushed in, as if to replace a vacuum, by the secure and continued existence that one saw in shops and homes and markets. The campus became a plain after an ancient, obscure battle, void alike of persons and significance; and the buildings along the Row took on an air of indifference, as if protesting that they had nothing to do with what fronted or backed them. Each brick and window and path placed itself in isolation from its surroundings; and yet even this passive detachment was negated by the general torpor that enveloped everything.

But if one looked closely and carefully, the patient still showed a pulse, however feeble or intermittent. In the few open fraternities, seniors were engaged on theses or GI papers; over at New Hamp, actual dorm activity was simulated in almost convincing detail; the library attempted to rouse itself by listlessly and inconveniently opening its doors daily from 8 to 5, Saturdays and Sundays excluded; and Hopkins Center, in its perversity, never really bothered to notice the change in the College, and stubbornly slaved away at distributing mail, making sandwiches, and changing dollar bills in one of its miraculous machines.

But such relics and remnants were touched into purposeful reality only by the weather, which for the most part was a revelation of belated warmth. Skies lightened to an amiable blue, and the heat began to make jagged slices into the snow, filing an edge of frost here, rounding off a corner there; and finally, gathering its forces, it wreaked general depredation all over campus. The white retreated day by day; the gurgle of water, running into drains that had not been seen since Thanksgiving, compensated for the loss of footfalls; and long hidden turf slowly revealed itself as moist brown velvet in places flushed an unnatural green. The remaining spectators were of course considerably cheered by this elevating spectacle, and when the wandering tribe returned on April 1 with tales of bacchanales in Bermuda and fetes in Florida, and expressed wonder at the onslaught of spring, those who stayed behind could at least take a certain pleasure in thinking that they had seen it happen.

THEN, as spring term started, everyone became aware of two notable changes in the College, one hardly less ingratiating than the other. The more conspicuous, and thus possibly the more odious of the two, is the fallout shelter signs posted at strategic points around the campus. These signs, unfortunately painted on a very durable metal, were evolved with the clear intention of attracting the attention by offending the eye; nothing else could explain their black and yellow hideousness and specific resemblance to placards in a shooting gallery. (Not a bad idea, actually, for their ultimate use.)

But their unashamed ugliness is not half as perplexing as their supposed function, which receives my unqualified nomination as Enigma of the Year. The determining factor in selecting or rejecting an edifice as a potential shelter site was apparently whether or not the place had a basement or its equivalent, which seems sensible enough as far as it goes; but the pure fantasy of the whole conception is evident in the various assigned capacities that form the bull's-eyes of the aforementioned black-and-yellow targets. Streeter, for instance, has official room for 59 people, which certainly does not begin to provide for its total population; and the same is true of Lord (also 59), Gile (56), Middle Mass (94), and others. Butterfield, however, has stowage for no less than 100, which is far more than it needs; while dorms like Hitchcock, Topliff, and Richardson have no shelters at all, which obviously means that their inhabitants will be forced to seek asylum elsewhere in case of enemy attack. This eventuality, in fact, would under such a quota system lead inevitably to confusion and endless amounts of wasted motion. One can imagine the panic-stricken dwellers of, let us say, Hitchcock reacting to the wail of the air raid sirens in somewhat the following manner:

Dorm Chairman (to his assembled charges): Look, will you calm down?

Everything's going to be all right. What's the situation in Butterfield, Stanislaus?

Stanislaus: They're full, chief.

D.C.: Full? They've got room for a hundred people!

Stan: Yeah, but they've got all the crowd from Zeta Psi there — it's strictly SRO.

D.C. (to a student who has just rushed in): Froelich! What's happened? Didn't you get into Streeter?

Froelich (panting): Not a chance — they're locked tight. I pounded on the door and they threw frisbees at me.

D.C. (desperately): What about Middle Mass then?

Stan: Out of the question. They're being mobbed by some guys from Richardson - I tried to get in and nearly lost my distilled water.

D.C. (stunned): But - don't you see? - this means - we're - doomed! ...

And they stand staring at each other as the sky turns white. Which is sufficient proof that only the most devious reasoning could ever pretend that the fallout shelter signs serve any unique purpose except that of irritating the sensibilities. It is highly unlikely in the first place that Hanover would ever be attacked directly; and thus there is little need to display such monstrosities so publicly. Why, one asks, could not every student and college employee simply be informed of the shelter facilities on campus and a ssigned to one of them in the event of an emergency? Why, when the same effect could have been achieved with infinitely more taste, was it thought necessary to blight the attractiveness of the College, not even sparing Sanborn House or Dartmouth Hall, with these wretched reminders of the atomic age? No one so far has attempted an answer; and certainly on this occasion an answer is required.

The other change, while not as important, is equally exacerbating: to wit, the installation of speakers in all three dining rooms at Thayer Hall in order to pipe in music during meals. This is a gesture of distressing conventionality, especially when you consider both the function and the quality of the material utilized. The music, it should be said at the outset, is the merest soapsuds, the same dreary, vapid emulsion usually vended in record shops under titles like "Candlelight and Neurasthenia" and "Gems from The Student Shill played by the Maraschino Strings"; and the sound that emerges is banal and superannuated to the point where it suggests a soundtrack from a Hollywood comedy of the 1930's - one expects at any moment to see Irene Dunne emerge from the kitchen and begin humorously berating Cary Grant for losing his meal ticket. The idea behind all this is apparently to soothe, or dull, the savage temper of the typical Dartmouth man while at the same time drowning out conversation and connected thought with a bath of melodic oatmeal. When you contemplate both the fallout-shelter signs and the speakers in Thayer, the conclusion is inescapable: although it has often been observed that a change is not always an improvement, it obviously has not been observed quite often enough.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH IN THE PEACE CORPS

May 1963 By Clifford L. Jordan Jr. '45 -

Feature

FeatureALEMBIC IN LIMBO: A College Dialogue

May 1963 By DAVID McCORD -

Feature

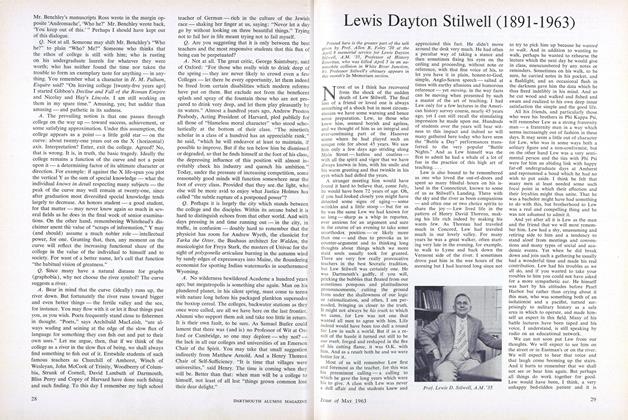

FeatureLewis Dayton Stilwell (1891-1963)

May 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

May 1963 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, WILLIAM T. WENDELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1963 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK -

Article

ArticleHANOVER DOGS 1963

May 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

CARL MAVES '63

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

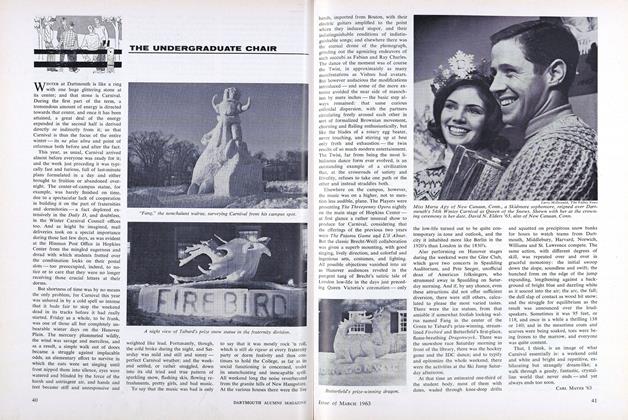

MARCH 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1963 By CARL MAVES '63

Article

-

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB ACQUIRES TRACT OF LAND

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleHis Medical Monument

November 1959 -

Article

ArticleOn Tune 1, The Rev. Telfer Mook '38

December 1960 -

Article

Article1964 Football Schedule

DECEMBER 1963 -

Article

ArticleIndian Medical Program

JUNE 1971 -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

December, 1928 By Samson Occom