I REMEMBER once standing with him on a street overlooking the campus. As we watched the students going back and forth I was struck by the youthful appearance of the men of Dartmouth. To me, a very recent alumnus, the upperclassmen looked like high school seniors and the freshmen mere grammar school boys. It was the beginning of a new college year and Lew said: "Look at all the nice tender freshmen! I can hardly wait to start operating on their brains." If I do not quote him verbatim, that was the gist of it; he was relishing the prospect of a new set of young minds to stir up. He had a freshman course to give and he was looking forward to it with what looked like mischievous glee.

He was a controversial figure in those days ... this is about a specific period at Dartmouth (1924-28) and is not to be taken out of its historical context. I know little of events in Hanover since those distant days; whether they bear out, complement or contradict this piece. He was a controversial figure then. Some thought of him as a formidable iconoclast who tore students loose from their cherished beliefs. I heard a professor in another class criticize Lew as "one who strips students of their ideals and leaves them nothing to fall back on." Some thought of him as a mere debunker of middle-class prejudices. Some took him for an emancipator who freed his pupils from illusions and taught them to question beliefs with intellectual honesty. I guess Lew thought he was using the classic Socratic method of teaching by asking questions. He had enough faith in mankind to think, that if men know how to reason clearly and honestly they can come up with the "right" conclusions sooner or later. If he liked reason he loved paradox. He enjoyed playing with ideas to a point that often led him to theatrics. If there was an area in which those who knew him were willing to agree it was probably only that he loved teaching. That much about him was not controversial.

Adept with audiences, he would put them through paces of feeling surprised, amused, indignant, incredulous, pretty much what he wanted, by turns. He could manage a session with a sense of timing, tossing out a controversial statement at the right point before the end so that a crowd of students would gather clamoring about his desk, demanding fuller explanations, trying to prolong the discussion while he smilingly folded up his notes. He liked to leave his students up in the air so they could find a way down by themselves.

He did noit hesitate to resort on occasion to a trick to illustrate a point. Iremember once when he was having hard going explaining the difference between Argument and Discussion he fixed his eyes on an unsuspecting lad in the front row and fairly shouted: "You're a goddam fool!" Then, when the class drew back in stunned silence for what he considered a long enough period to stir thought, he explained: "You see when I talk like that we can't get anywhere. But in a calm atmosphere where we observe mutual consideration it is possible we may arrive at something." The student told me afterwards that he resented being pressed into service without previous consultation just to help make a point, but I am sure the concept of Calm Discussion lingered on in his memory.

At times his theatrics overflowed the lecture hall onto the campus. I heard of one occasion when he was the center of a crowd engaged in such an idea-dramatization. The topic was Passive Resist- ance. Lew's assertion in class that if one remains completely passive others will not employ violence was challenged by a prominent athlete in the class, whereupon Lew said he would dare the fellow to knock him down if he stood before him doing "nothing." The entire class, augmented by many students who hap- pened to be out in the noon recess, formed a small circle on the greensward to watch the athlete tumble Lew to the ground, thus "winning the bet" as my informant told me. Though as to that, I think Lew believed he had scored his point by getting his audience to think about the principles in other than a purely academic way.

Once an echo of one of his controversies even reached the New York newspapers. It was at the start, or just before the start, of World War II and he was quoted (or misquoted) as making a statement which ran counter to some strong ideas most of us held to. I remember reading about it at the time with annoyance, and some puzzlement. But, as I have been saying, he was a controversial figure.

On the street - and now that I think of it, he spent most of his time on the street - he was usually called by his first name, not common with professors in those days. He was uncomfortable with the over-respectful boys who sirred him and professored him, but did not mind being called Mister on short acquaintance. "It's when a man calls me Stilwell that I feel his intent is hostile" he once told me. I believe I called him "Sir" at first but sensed the wrongness of it in short order.

He stood on the sidewalks of Hanover by the hour, usually with several companions. Before one left another would join the group so that he tended to be in the middle of a constantly enlarging clutch of students. His trips across the campus were frequently at the center of a phalanx. Sometimes students queued up to get in a few words.

And there was his laugh. It was too loud. You could hear it all over Hanover. Often when I was looking for him I knew my search was at an end when I heard it strike through a door or echo down a leafy side street. Some distrusted it as an affectation. "Those loud laughers have no sense of humor" I heard from a man who did not know him very well. Others found it comforting... something to fill an awkward silence. (How embarrassed we all were in those days!) It was, of course, or had started out to be, partly a device to cover the very embarrassment which it called attention to. But it was not an insinuating or obsequious laugh. Some of us used to try to provoke it, saying something just to hear it burst out and reverberate up and down the street. Sometimes it helped to wring a few extra drops of humor out of what was being talked about. It was not the kind of laugh you heard above the crowd at a lecture or the theatre, as I recall, unless Lew was doing the lecturing himself. As I grew to become his friend I was less conscious of it. Perhaps he laughed less loudly in private. I had forgotten it these many years until I started thinking about him. Now I can almost hear it again and it provokes the same mixed feelings it used to.

I first met Lew when he came home for a weekend with my brother who went to Dartmouth ahead of me. From that brief encounter it seemed natural to look him up when I went to college, and to go on to become a close friend. There was a little snobbery on my part at first. I enjoyed being seen with and on first-name terms with one of the faculty. But it was because I admired him that we saw each other at increasingly frequent intervals for four years, taking canoe excursions afternoons, driving about the countryside near Hanover in his first car, loafing at the cabin down river from Hanover which he had permission to use, or eating together.

Looking back at that time I am a little surprised that it didn't occur to me to doubt my ability to be as interesting company for a man fifteen years my senior as he was to me. I give credit to Lew for never letting me feel that my ideas were trite to him. I think his interest in watching a young mind develop was so great that he was not bored. His closest friends, as I remember, were the students. He had friends among his colleagues, too, but it was more often with students that he went canoeing, driving, or dining.

I was not conscious that he was older. He made no attempt to hide his weaknesses or feelings from those of us who went about with him. We knew of his disappointments, his frequent and usually short-lived efforts to give up smoking, his inexpertness with anything mechanical, just as we knew his favorite authors and his latest enthusiasms. He shared his snap judgments, his insights and his convictions with us. We deferred to him on his specialty: history. And he deferred to us on the specialties we believed we were in process of acquiring.

At a time in my scholastic life when I had come to think of all teachers as being on "the other side," as pompous adults with a bill of goods (quite unrelated to the world as far as I could see) to foist upon me, Lew's lack of pretense, his genuine informality, came as a revelation. From him I discovered that a teacher can be a human being. Stated like this I know it sounds pretty tame. But to me, the four-year product of a conventional snobbish prep school, it constituted an awakening. It is possible I would have made the same friends among fellow students and faculty that I went on to make anyway. But I see no reason to be less grateful to Lew for that. The important thing for me is that he was there, just when I needed him the most to widen my sights.

There must be others, many others, who feel similarly and who can probably express what I am trying to say about Lew with more depth and precision. But I cannot resist writing this now any more than as a student I could resist joining the group that was continually forming around him, eager to take part in the lively discussions he enjoyed being the center of.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

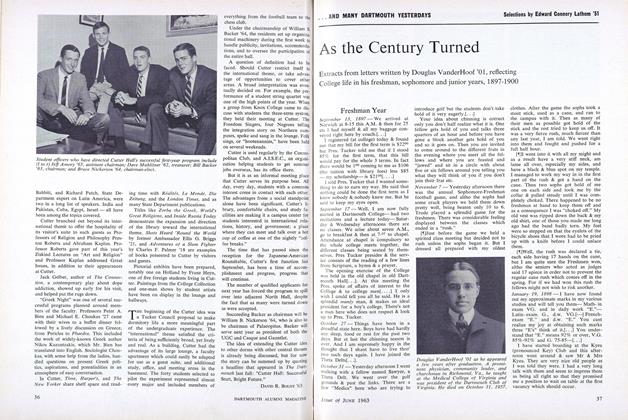

FeatureAs the Century Turned

June 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

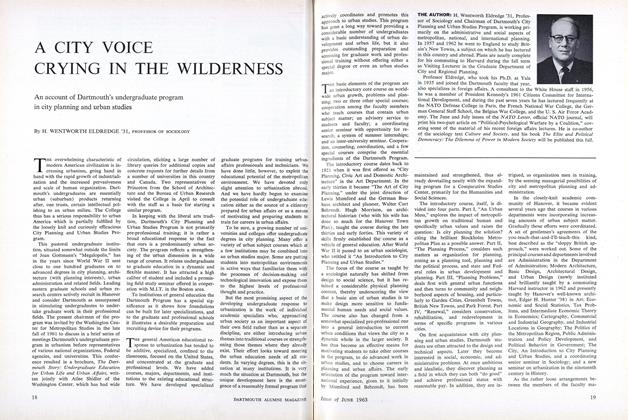

FeatureA CITY VOICE CRYING IN THE WILDERNESS

June 1963 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Feature

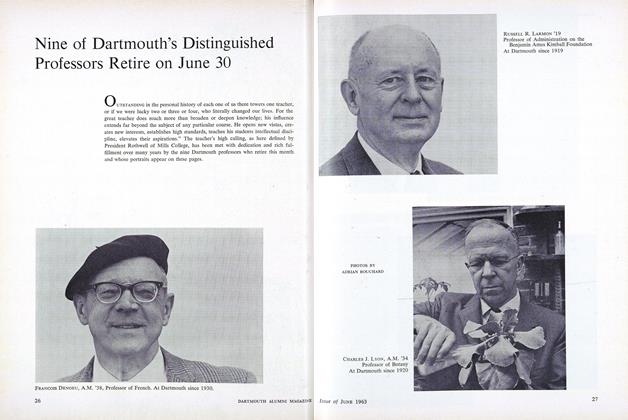

FeatureNine of Dartmouth's Distinguished Professors Retire on June 30

June 1963 -

Feature

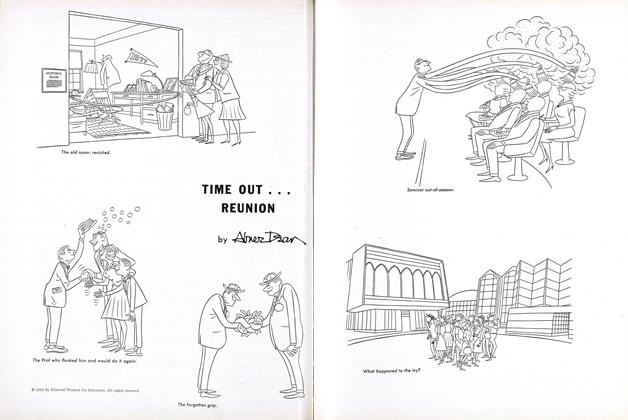

FeatureTIME OUT ... REUNION

June 1963 By Abnez Dean -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1963 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, WILLIAM T. WENDELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

June 1963 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT

JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28

Books

-

Books

BooksA SHORT FRENCH GRAMMAR FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS

May 1940 By Charles R. Barley -

Books

BooksTHE JADE NECKLACE OF LIN SAN KWEI.

MARCH 1959 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksSCENERY FOR THE THEATRE: THE ORGANIZATION, PROCESSES, MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES USED TO SET THE STAGE.

MAY 1972 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF MOUNT WASHINGTON.

June 1960 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksRELATION OF FAILURE TO PUPIL SEATING.

December 1932 By W. R. W. -

Books

BooksTHE ELECTRIC INTERURBAN RAILWAYS IN AMERICA.

June 1960 By WAYNE G. BROEHL JR.