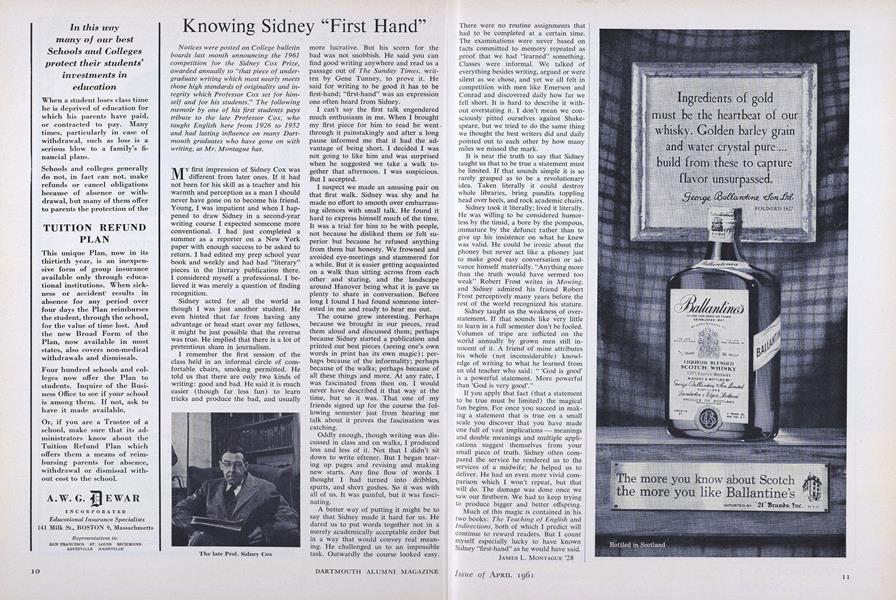

Notices were posted on College bulletinboards last month announcing the 1961competition for the Sidney Cox Prize,awarded annually to "that piece of undergraduate writing which most nearly meetsthose high standards of originality and integrity which Professor Cox set for himself and for his students." The followingmemoir by one of his first students paystribute to the late Professor Cox, whotaught English here from 1926 to 1952and had lasting influence on many Dartmouth graduates who have gone on withwriting, as Mr. Montague has.

MY first impression of Sidney Cox was different from later ones. If it had not been for his skill as a teacher and his warmth and perception as a man I should never have gone on to become his friend. Young, I was impatient and when I happened to draw Sidney in a second-year writing course I expected someone more conventional. I had just completed a summer as a reporter on a New York paper with enough success to be asked to return. I had edited my prep school year book and weekly and had had "literary" pieces in the literary publication there. I considered myself a professional. I believed it was merely a question of finding recognition.

Sidney acted for all the world as though I was just another student. He even hinted that far from having any advantage or head start over my fellows, it might be just possible that the reverse was true. He implied that there is a lot of pretentious sham in journalism.

I remember the first session of the class held in an informal circle of comfortable chairs, smoking permitted. He told us that there are only two kinds of writing: good and bad. He said it is much easier (though far less fun) to learn tricks and produce the bad, and usually more lucrative. But his scorn for the bad was not snobbish. He said you can find good writing anywhere and read us a passage out of The Sunday Times, written by Gene Tunney, to prove it. He said for writing to be good it has to be first-hand; "first-hand" was an expression one often heard from Sidney.

I can't say the first talk engendered much enthusiasm in me. When I brought my first piece for him to read he went through it painstakingly and after a long pause informed me that it had the advantage of being short. I decided I was not going to like him and was surprised when he suggested we take a walk together that afternoon. I was suspicious. But I accepted.

I suspect we made an amusing pair on that first walk. Sidney was shy and he made no effort to smooth over embarrassing silences with small talk. He found it hard to express himself much of the time. It was a trial for him to be with people, not because he disliked them or felt superior but because he refused anything from them but honesty. We frowned and avoided eye-meetings and stammered for a while. But it is easier getting acquainted on a walk than sitting across from each other and staring, and the landscape around Hanover being what it is gave us plenty to share in conversation. Before long I found I had found someone interested in me and ready to hear me out.

The course grew interesting. Perhaps because we brought in our pieces, read them aloud and discussed them; perhaps because Sidney started a publication and printed our best pieces (seeing one's own words in print has its own magic); perhaps because of the informality; perhaps because of the walks; perhaps because of all these things and more. At any rate, I was fascinated from then on. I would never have described it that way at the time, but so it was. That one of my friends signed up for the course the following semester just from hearing me talk about it proves the fascination was catching.

Oddly enough, though writing was discussed in class and on walks, I produced less and less of it. Not that I didn't sit down to write oftener. But I began tearing up pages and revising and making new starts. Any fine flow of words I thought I had turned into dribbles, spurts, and short gushes. So it was with all of us. It was painful, but it was fascinating.

A better way of putting it might be to say that Sidney made it hard for us. He dared us to put words together not in a merely academically acceptable order but in a way that would convey real meaning. He challenged us to an impossible task. Outwardly the course looked easy. There were no routine assignments that had to be completed at a certain time. The examinations were never based on facts committed to memory repeated as proof that we had "learned" something. Classes were informal. We talked of everything besides writing, argued or were silent as we chose, and yet we all felt in competition with men like Emerson and Conrad and discovered daily how far we fell short. It is hard to describe it without overstating it. I don't mean we consciously pitted ourselves against Shakespeare, but we tried to do the same thing we thought the best writers did and daily pointed out to each other by how many miles we missed the mark.

It is near the truth to say that Sidney taught us that to be true a statement must be limited. If that sounds simple it is so rarely grasped as to be a revolutionary idea. Taken literally it could destroy whole libraries, bring pundits toppling head over heels, and rock academic chairs.

Sidney took it literally; lived it literally. He was willing to be considered humorless by the timid, a bore by the pompous, immature by the defunct rather than to give up his insistence on what he knew was valid. He could be ironic about the phoney but never act like a phoney just to make good easy conversation or advance himself materially. "Anything more than the truth would have seemed too weak" Robert Frost writes in Mowing, and Sidney admired his friend Robert Frost perceptively many years before the rest of the world recognized his stature.

Sidney taught us the weakness of overstatement. If that sounds like very little

to learn in a full semester don't be fooled. Volumes of tripe are inflicted on the world annually by grown men still innocent of it. A friend of mine attributes his whole (not inconsiderable) knowledge of writing to what he learned from an old teacher who said: " 'God is good' is a powerful statement. More powerful than 'God is very good'."

If you apply that fact (that a statement to be true must be limited) the magical fun begins. For once you suceed in making a statement that is true on a small scale you discover that you have made one full of vast implications - meanings and double meanings and multiple applications suggest themselves from your small piece of truth. Sidney often compared the service he rendered us to the services of a midwife; he helped us to deliver. He had an even more vivid comparison which I won't repeat, but that will do. The damage was done once we saw our firstborn. We had to keep trying to produce bigger and better offspring.

Much of this magic is contained in his two books: The Teaching of English and Indirections, both of which I predict will continue to reward readers. But I count myself especially lucky to have known Sidney "first-hand" as he would have said.

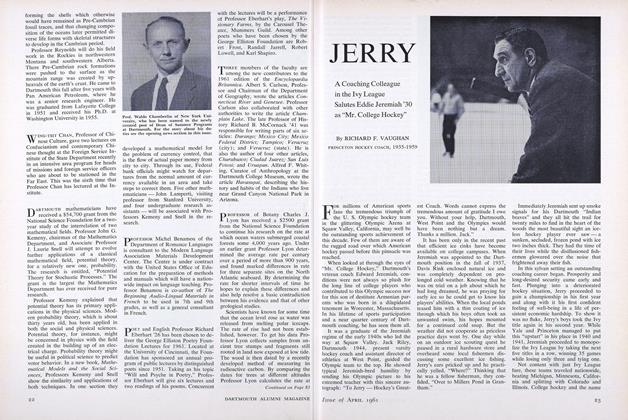

The late Prof. Sidney Cox

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

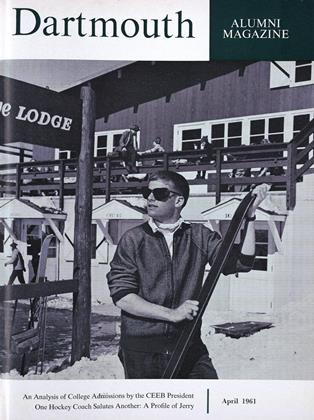

FeatureJERRY

April 1961 By RICHARD F. VAUGHAN -

Feature

FeatureTwo Questions About Getting Into College

April 1961 By FRANK H. BOWLES -

Feature

FeatureHanover Marks Its 200th Year

April 1961 By D.E.O. -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

April 1961 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

April 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, TOM H. ROSENWALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

April 1961 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28

Article

-

Article

ArticleNOTES

May 1912 -

Article

ArticleHONOR TO MR. AND MRS. EDWARD TUCK

February 1917 -

Article

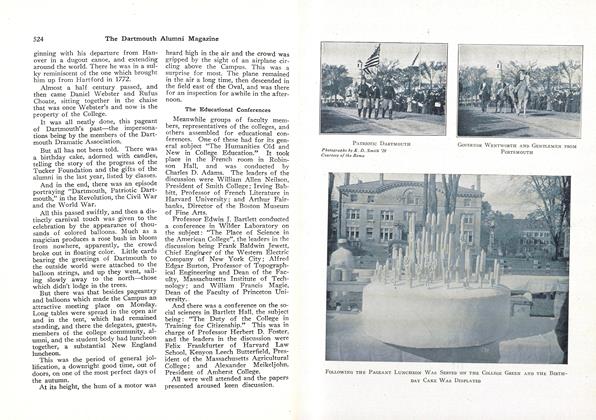

ArticleMUSICAL CLUBS

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY MEMBERS PROMINENT IN LONGHURST PINAFORE PRODUCTION

January, 1925 -

Article

ArticleStill in Shape

November 1956 -

Article

ArticleIndians Scout for the Fleet

March 1942 By LT. E. F. PLANK, UNITED STATES NAVAL RESERVE