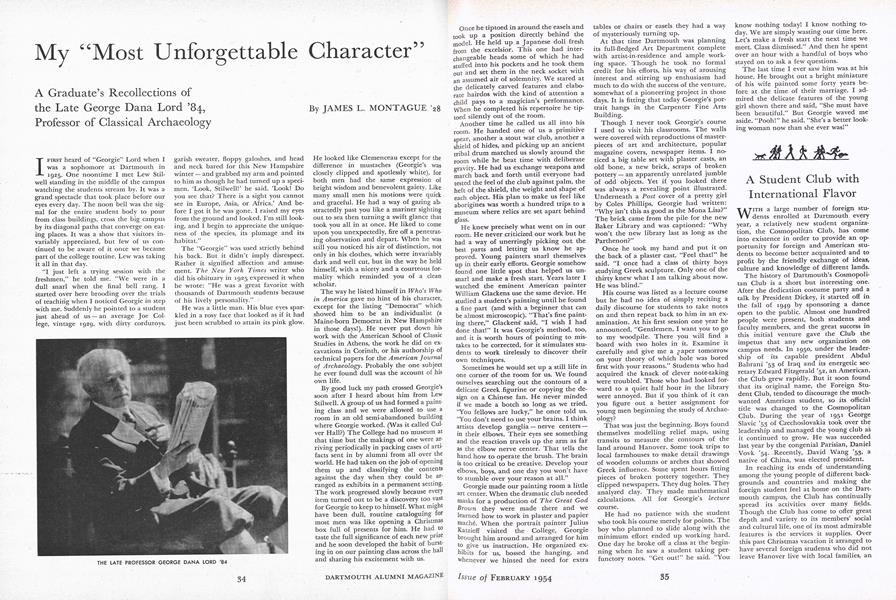

A Graduate's Recollections of the Late George Dana Lord '84, Professor of Classical Archaeology

I FIRST heard of "Georgie" Lord when I was a sophomore at Dartmouth in 1925. One noontime I met Lew Stilwell standing in the middle of the campus watching the students stream by. It was a grand spectacle that took place before our eyes every day. The noon bell was the signal for the entire student body to pour from class buildings, cross the big campus by its diagonal paths that converge on eating places. It was a show that visitors invariably appreciated, but few of us continued to be aware of it once we became part of the college routine. Lew was taking it all in that day.

"I just left a trying session with the freshmen," he told me. "We were in a dull snarl when the final bell rang. I started over here brooding over the trials of teaching when I noticed Georgie in step with me. Suddenly he pointed to a student just ahead of us - an average Joe College, vintage 1929, with dirty corduroys, garish sweater, floppy galoshes, and head and neck bared for this New Hampshire winter - and grabbed my arm and pointed to him as though he had turned up a specimen. 'Look, Stilwell!' he said. 'Look! Do you see that? There is a sight you cannot see in Europe, Asia, or Africa.' And before I got it he was gone. I raised my eyes from the ground and looked. I'm still looking, and I begin to appreciate the uniqueness of the species, its plumage and its habitat."

The "Georgie" was used strictly behind his back. But it didn't imply disrespect. Rather it signified affection and amusement. The New York Times writer who did his obituary in 1925 expressed it when he wrote: "He was a great favorite with thousands of Dartmouth students because of his lively personality."

He was a little man. His blue eyes sparkled in a rosy face that looked as if it had just been scrubbed to attain its pink glow. He looked like Clemenceau except for the difference in mustaches (Georgie's was closely clipped and spotlessly white), for both men had the same expression of bright wisdom and benevolent gaiety. Like many small men his motions were quick and graceful. He had a way of gazing abstractedly past you like a mariner sighting out to sea then turning a swift glance that took you all in at once. He liked to come upon you unexpectedly, fire off a penetrating observation and depart. When he was still you noticed his air of distinction, not only in his clothes, which were invariably dark and well cut, but in the way he held himself, with a nicety and a courteous formality which reminded you of a clean scholar.

The way he listed himself in Who's Whoin America gave no hint of his character, except for the listing "Democrat" which showed him to be an individualist (a Maine-born Democrat in New Hampshire in those days!). He never put down his work with the American School of Classic Studies in Athens, the work he did on excavations in Corinth, or his authorship of technical papers for the American Journalof Archaeology. Probably the one subject he ever found dull was the account of his own life.

By good luck my path crossed Georgie's soon after I heard about him from Lew Stilwell. A group of us had formed a painting class and we were allowed to use a room in an old semi-abandoned building where Georgie worked. (Was it called Culver Hall?) The College had no museum at that time but the makings of one were arriving periodically in packing cases of artifacts sent in by alumni from all over the world. He had taken on the job of opening them up and classifying the contents against the day when they could be arranged as exhibits in a permanent setting. The work progressed slowly because every item turned out to be a discovery too vast for Georgie to keep to himself. What might have been dull, routine cataloguing for most men was like opening a Christmas box full of presents for him. He had to taste the full significance of each new prize and he soon developed the habit of bursting in on our painting class across the hall and sharing his excitement with us.

Once he tiptoed in around the easels and took up a position directly behind the model. He held up a Japanese doll fresh from the excelsior. This one had interchangeable heads some of which he had stuffed into his pockets and he took them out and set them in the neck socket with an assumed air of solemnity. We stared at the delicately carved features and elaborate hairdos with the kind of attention a child pays to a magician's performance. When he completed his repertoire he tiptoed silently out of the room.

Another time he called us all into his room. He handed one of us a primitive spear, another a stout war club, another a shield of hides, and picking up an ancient tribal drum marched us slowly around the room while he beat time with deliberate gravity. He had us exchange weapons and march back and forth until everyone had tested the feel of the club against palm, the heft of the shield, the weight and shape of each object. His plan to make us feel like aborigines was worth a hundred trips to a museum where relics are set apart behind glass.

He knew precisely what went on in our room. He never criticized our work but he had a way of unerringly picking out the best parts and letting us know he approved. Young painters snarl themselves up in their early efforts. Georgie somehow found one little spot that helped us unsnarl and make a fresh start. Years later I watched the eminent American painter William Glackens use the same device. He studied a student's painting until he found a fine part (and with a beginner that can be almost microscopic). "That's fine painting there," Glackens said, "I wish I had done that!" It was Georgie's method, too, and it is worth hours of pointing to mistakes to be corrected, for it stimulates students to work tirelessly to discover their own techniques.

Sometimes he would set up a still life in one corner of the room for us. We found ourselves searching out the contours of a delicate Greek, figurine or copying the design on a Chinese fan. He never minded if we made a botch so long as we tried. "You fellows are lucky," he once told us. "You don't need to use your brains. I think artists develop ganglia - nerve centers - in their elbows. Their eyes see something and the reaction travels up the arm as far as the elbow nerve center. That tells the hand how to operate the brush. The brain is too critical to be creative. Develop your elbows, boys, and one day you won't have to stumble over your reason at all."

Georgie made our painting room a little art center. When the dramatic club needed masks for a production of The Great GodBrown they were made there and we learned how to work in plaster and papier maché. When the portrait painter Julius Katzieff visited the College, Georgie brought him around and arranged for him to give us instruction. He organized exhibits for us, bossed the hanging, and whenever we hinted the need for extra tables or chairs or easels they had a way of mysteriously turning up.

At that time Dartmouth was planning its full-fledged Art Department complete with artist-in-residence and ample working space. Though he took no formal credit for his efforts, his way of arousing interest and stirring up enthusiasm had much to do with the success of the venture, somewhat of a pioneering project in those days. It is fitting that today Georgie's portrait hangs in the Carpenter Fine Arts Building.

Though I never took Georgie's course I used to visit his classrooms. The walls were covered with reproductions of masterpieces of art and architecture, popular magazine covers, newspaper items. I noticed a big table set with plaster casts, an old bone, a new brick, scraps of broken pottery - an apparently unrelated jumble of odd objects. Yet if you looked there was always a revealing point illustrated. Underneath a Post cover of a pretty girl by Coles Phillips, Georgie had written: "Why isn't this as good as the Mona Lisa? The brick came from the pile for the new Baker Library and was captioned: "Why won't the new library last as long as the Parthenon?"

Once he took my hand and put it on the back of a plaster cast. "Feel that!" he said. "I once had a class of thirty boys studying Greek sculpture. Only one of the thirty knew what I am talking about now. He was blind."

His course was listed as a lecture course but he had no idea of simply reciting a daily discourse for students to take notes on and then repeat back to him in an examination. At his first session one year he announced, "Gentlemen, I want you to go to my woodpile. There you will find a board with two holes in it. Examine it carefully and give me a tomorrow on your theory of which hole was bored first with your reasons." Students who had acquired the knack of clever note-taking were troubled. Those who had looked forward to a quiet half hour in the library were annoyed. But if you think of it can you figure out a better assignment for young men beginning the study of Archaeology?

That was just the beginning. Boys found themselves modelling relief maps, using transits to measure the contours of the land around Hanover. Some took trips to local farmhouses to make detail drawings of wooden columns or arches that showed Greek influence. Some spent hours fitting pieces of broken pottery together. They clipped newspapers. They dug holes. They analyzed clay. They made mathematical calculations. All for Georgie's lecture course.

He had no patience with the student who took his course merely for points. The boy who planned to slide along with the minimum effort ended up working hard. One day he broke off a class at the beginning when he saw a student taking perfunctory notes. "Get out!" he said. "You know nothing today! I know nothing today. We are simply wasting our time here. Let's make a fresh start the next time we meet. Class dismissed." And then he spent over an hour with a handful of boys who stayed on to ask a few questions.

The last time I ever saw him was, at his house. He brought out a bright miniature of his wife painted some forty years before at the time of their marriage. I admired the delicate features of the young girl shown there and said, "She must have been beautiful." But Georgie waved me aside. "Pooh!" he said. "She's a better looking woman now than she ever was!"

THE LATE PROFESSOR GEORGE DANA LORD '84

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Faculty Policies

February 1954 By DONALD H. MORRISON '47h -

Feature

FeatureTestament of a Teacher

February 1954 By ROYAL CASE NEMIAH '23h -

Feature

FeatureThe Teacher of Social Science and the World Crisis

February 1954 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

February 1954 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, JOHN B. WOLFF JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

February 1954 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, DR. COLIN C. STEWART 3RD

JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28

Features

-

Feature

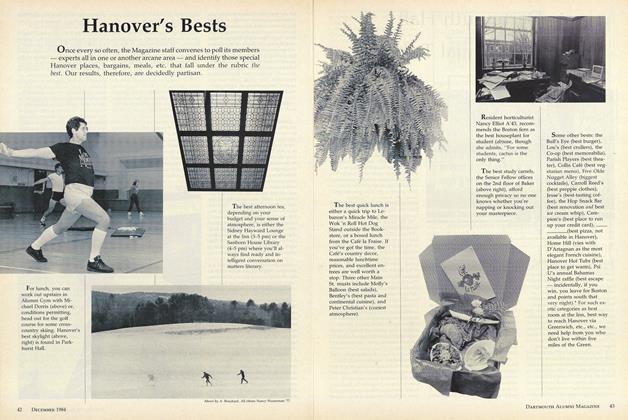

FeatureHanover's Bests

DECEMBER 1984 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

FEATURE

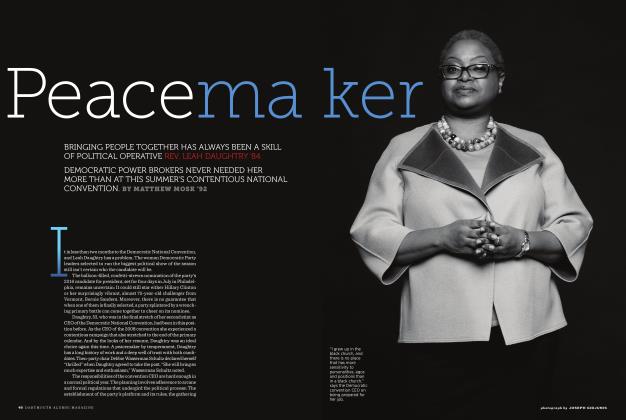

FEATUREPeacemaker

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

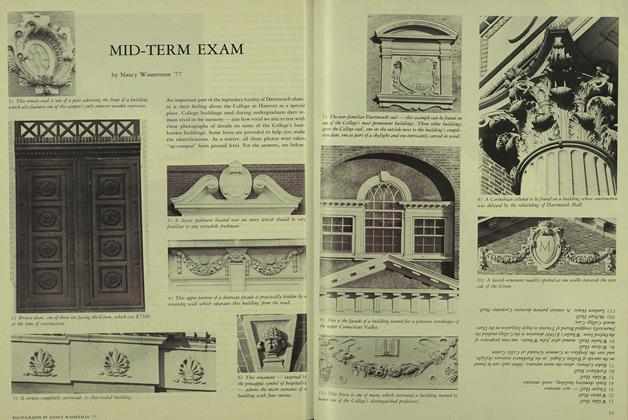

FeatureMID-TERM EXAM

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureFarewell Dear (BOOZY, BRAWLING) Davis

January 1976 By ROBERT SULLIVAN