To THE TRUSTEES OF DARTMOUTHCOLLEGE.

GENTLEMEN:

If there has been any deterioration in the Great Seal on the Tower of Baker Library, please don't blame the contractor. It's my fault.

D. G. GRAHAM '28

It would be wonderful if action could be stopped at appropriate intervals during our lives, and a prompter off-stage could say, "Now mark this next incident well. It may not seem important at the moment, but you'll see."

Unhappily, that isn't the way it goes. It's only years later that we say as Emily does in "Our Town," "It goes so fast. We don't have time to look at one another."

I wish that I had looked harder at the foreman. Today I can't recall his name or his appearance, but I shall never forget what he did.

My last two years at Dartmouth were pretty tough financially. Waiting on table at the old Green Lantern took care of my board, but during the summer I had to lay by whatever nest-egg I could toward other expenses of the coming term. Consequently I was more than a little concerned in June of 1927 when my junior year ended and none of my leads for a summer job had come through.

In the weeks past, I had casually noted that excavation for the new Baker Library had been completed and actual construction started, but only extreme necessity persuaded me - 6'4" of pure bone weighing a smart 150 pounds - that the project was badly in need of my assistance.

One afternoon I put on some neatlypressed gray flannels and a crinkling fresh shirt and went over to the scene of operations. I seem to recall that I asked a workman where I could find the "manager." He asked if I meant the foreman, I said that I guessed I did, and the man pointed him out.

Here should come a description of the foreman, how he looked, what he wore, the many moments he must have spent sizing up the earnest young beanpole who was confessing that he had never had any experience as a construction worker, but was promising to prove that he was worth every penny of whatever salary was offered. Was there a twinkle in his eye or was he coldly deadpan when he said, "You can start Monday morning. Wear some old clothes."

My oldest clothes were a dirty sport shirt and some impressed Campion slacks with 22-inch cuffs in the fashion of the period, so that with every step they swished around as if I were wearing a skirt on each leg. Thus attired, I reported to the foreman.

His instructions were brief.

"Pick up a hod. The mortar is over there."

For the next three days I climbed rough-built ladders with a hodful of mortar on my shoulder. I might have been in grave danger had not the foreman called me over midway through the first morning. With no comment he tied a rag around each of my ankles to furl the flopping cuffs.

Toward noon of the fourth day, the foreman dropped by. The carpenters were short a man to carry lumber and be of general assistance. He was shifting me.

Here again I can only speculate.

Had he put me on the hod-carrying assignment to test my mettle? Had be been sure that one day of it would cure me of wanting to be a construction man? Since I didn't fold up, did his good New England conscience obligate him to keep me on the rest of the summer?

Whatever his motivation may have been, I can now confess that two more days of climbing ladders with a hod on my shoulder would have won the contest for him. In spite of the fact that I came to work the second morning with a folded towel over my shoulder pinned to my undershirt, the flesh was bruised and raw and my collar-bone ached to the marrow. Two more days of it in order to collect a full week's salary was all I was planning to take.

Working with the carpenters was a pleasant change. While no time was wasted, there were opportunities for conversation and banter. They were natives of New Hampshire and Vermont, kindly sun-marked men who knew what they were helping to build, and took a quiet pride in it. They would ask my opinion on a variety of subjects, and listen to my answers with flattering attention. (I hope I didn't sound too foolish, but my observations must have brightened their day.)

Week by week the Library took on character — an impressive shell with form and dignity. By August, work was already well along on the Tower.

One' morning a small yell started in the distance, grew louder as it was repeated from mouth to mouth, and became words by the time it reached the yard where I was squaring up some boards.

"Graham! Boss wants you!

Where was the boss? Somewhere up there.

I crossed the yard and entered the damp cool of the building. Up one flight of temporary stairs, another and another. Finally I found myself on the top scaffolding in the half-completed Tower. To right and left were waist-high masonry walls. In front of me was a huge rectangle of limestone - the back of the Dartmouth Great Seal which had just been set into place. The foreman stood there with five or six workmen, a pail of black gunk in one hand, a heavy brush in the other. He handed them to me.

"The back of the seal has to be painted with this stuff," he said. "Otherwise when we put the brickwork behind it, the acid in the mortar would eat into the limestone. Put it on good and thick and don't miss any spots."

I put it on good and thick and went over the whole surface a second time to make sure that I hadn't missed any spots. The foreman came back as I was finishing up.

"Looks all right to me," he said.

He stood looking at me for a moment as if waiting for me to say something. Since I didn't, he dismissed me with, "That's all."

When I got back to the yard where the carpenters were squaring and sawing in the dappled sunlight under the big elm, they wanted to know "what that was all about." I told them that the boss had called me up there to do some kind of crazy paint job, and got on with my work.

Many years later my wife and I were in Hanover so that she could see the Dartmouth campus I had told her so much about. As we stood on the steps of the Inn admiring the perfect proportions of the Baker Library, the Great Seal in the face of the Tower gleaming in the sun, I said, "You know, it's a funny thing. I feel as if I were almost a part of—"

I stopped as a memory hit me with physical force, the memory of a gangling youngster being summoned to the half-finished Tower on a sunny August morning, the man handing him a brush and a bucket of gunk and telling him what to do with it.

Of course! That was it!

The foreman had been old and wise enough to know, while I had been too callow even to be aware.

There had been half a dozen workmen standing around when I got there. Certainly any one of them could have done the job with no instruction, little thought, and more efficiency, but he had called me up to do it. He knew that the chore would have no special significance for one of his men, but for me, just possibly in years to come -

Is that what he was waiting for that day, some word or sign that would show him that I understood what he had done and why he had done it?

Yes, life does go so fast, and we don't really have time to look at one another.

It's later — 35 years later in this case — that you still go on wishing that there were some way to say 'thank you to a man understanding and foresighted enough to give a young man a memory he would treasure, without the boy's really being aware of what was happening at the time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAs the Century Turned

June 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureA CITY VOICE CRYING IN THE WILDERNESS

June 1963 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Feature

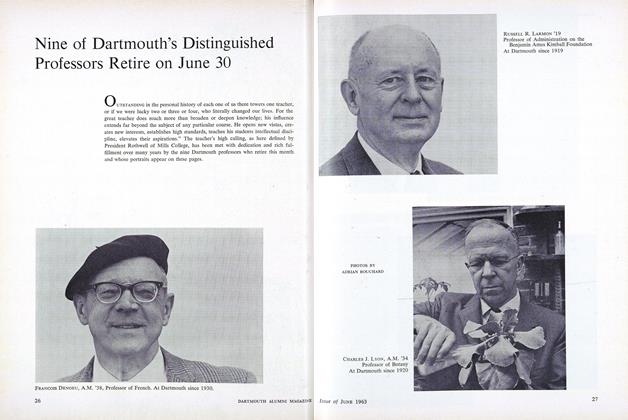

FeatureNine of Dartmouth's Distinguished Professors Retire on June 30

June 1963 -

Feature

FeatureTIME OUT ... REUNION

June 1963 By Abnez Dean -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1963 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, WILLIAM T. WENDELL -

Books

BooksLew Stilwell: A Fine Teacher

June 1963 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28

D. GORDON GRAHAM '28

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe retirement of President Eliot

January, 1909 -

Article

ArticleCongregation of the Arts

JUNE 1969 -

Article

ArticleArrivals and Departures

SEPTEMBER 1982 -

Article

ArticleThe Ford Peace Expedition of 1915

March 1961 By F. STIRLING WILSON '16 -

Article

ArticleWith the D. O. C.

May 1938 By John L. Steele '39 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott