As a boy, I knew that Catholics were storing guns in the cellars of their churches, against the day when they would arise and take over America for the Pope. My father told me so.

This was not just a report that he was passing along for my information; he was dogmatic about it. It was a burning personal conviction that he reiterated as frequently as occasion permitted.

The infection of this thinking might have gone even deeper had we known each other better, but he was a skilful physician on call at all hours of the day and night, so that he had little time to spend with his three sons.

It went deep enough as it was.

Walking by a Catholic church gave me the same frisson d'horreur that other boys traditionally feel when they have to pass a cemetery at night, and I preferred not to play with Leonard Grogan, who lived across the street. While he appeared to be no different from the rest of us, he was one of those, and regularly attended Mass and Confessional.

My attitude became somewhat ambivalent in my early teens. Leonard was a little older than the rest of us, and delighted in giving us vivid accounts of action and reaction in his explorations into sex. By his report, a surprising number of girls, some of whom we knew, were perfectly willing to go all the way. While we were enthralled, in a corner of my mind was the thought that only a benighted Irish Catholic would do such things and talk about them, thus revealing a complete lack of respect for the sanctity of young American womanhood. When I asked Leonard one day if he dared to confess these incidents to a priest, he said that he wouldn't dare not to. It turned out that he made these confessions in a remote church in the foreign section, in the assured belief that the French priest to whom he made them did not understand English.

When Leonard died, I missed his fine clinical descriptions, but I couldn't help feeling that perhaps our good Protestant God was aware of what had been going on, and had taken matters into His own hands.

My father ceased to be an active influence in my life when he and my mother were divorced, but by then the seeds of anti-Catholicism had been planted deeply. The raising of three sons became my mother's responsibility, with the court generously awarding her ten dollars a week to cover the cost of it.

I was in high school at the time, doing better-than-average work and getting excellent marks for it. I was qualified to go on to college and wanted to, but financially it was out of the question. Nevertheless, I applied for Dartmouth and was accepted. So what?

The "what" was the interest and humanitarianism of John S. Harrington, father of Clark Harrington. Clark, with whom I had been friendly during our high school days, had also been accepted for the Class of '28. Mr. Harrington thought it would be nice if his son and I could carry our friendship on into college, and being aware of our limited finances, offered to pay my expenses. (I relate the facts straightforwardly in order to get on with the story, but the sense of miracle is still with me.)

This arrangement lasted until the middle of my junior year. That was the time I chose to go through one of those not very original "What am I doing here?" phases. I wrote Mr. Harrington that I had decided not to stay on at Dartmouth. The fatherly counsel of Dean Laycock changed my mind, but the emotional adventure cost me my sponsor. Mr. Harrington decided - as I'm sure I would have in his place - not to invest further in a boy who had no better sense of direction.

For the next year and a half I worked, I borrowed, I eked, but at the end of my senior year I still owed a balance of $200 on my tuition, and I couldn't take my final exams unless it was paid.

I got half of it by winning the Barge Medal for Oratory. It had not occurred to me to enter the competition until I heard that the medal actually contained about ninety dollars' worth of gold. The morning after I won it I was at the bank bright and early to put it up as security for a loan of $100.

But the final hundred seemed impossible to get. The College and my fraternity had stretched policy to the limit to help me. My mother, who was working then, had done her utmost.

I was desperate, and time was growing short.

I wrote to my father, whom I had not seen nor heard from since the divorce.

The letter was not an easy one to write. I tried to convey a sense of the tremendous benefits obtained from my years in Hanover. I recounted some of my extracurricular activities - dramatics, being soloist of the Glee Club for four years, and its student leader when it won the Intercollegiate Glee Club Contest that spring in Carnegie Hall. All of this, I reminded him, I had done without his financial assistance. Now I needed it badly. Could he help?

His response was a curt note saying that he couldn't.

So that was that, and there was no more rope.

Two days later I was walking across campus protected from the magnificent May weather by a cloud of doom and despondency. I responded absent-mindedly to a cheery "Hi" from the organist and choirmaster of the little Catholic Church. An exchange of hi's had been the extent of our friendship, but this time he held out his hand and said, "May I walk along with you?"

I shook his hand and said, "Sure, come on."

As we fell into step he said, "I hope this won't embarrass you, but I understand you could use some help."

"Oh?"

"About your tuition. We have a small fund at the church to help boys when they need it. I know you're not one of us, but your music has brought so much pleasure to all of us since you've been here that we feel you deserve our help if you will accept it."

So it was the Catholic Church that enabled me to take my final exams.

And I failed to get my degree because Professor Mecklin flunked me in Comparative Religion.

Dear Professor Mecklin, wherever you are, how could you have known that I had had a practical lesson in Comparative Religion far more forceful than anything I could have learned from textbooks and lectures?

Now, thirty-seven years later, I can write the epilogue to bring the story full circle.

The lack of a formal degree from Dartmouth didn't bother me in later life. If I thought about it at all, it was only to confirm my conviction that no piece of parchment was required to persuade me that I had gotten full measure from the Hanover years.

Then in the fall of 1962 I began to think differently. With a son at Dartmouth [David P. Graham '65], it just wasn't neat for him to get his degree before the old man did. I wrote to Dean Seymour, who told me that I could be graduated with the Class of '63 if I made up the three credits I lacked. Why not see what Fairfield University had to offer?

The course I selected was "Social and Cultural History of the United States Since 1865," given by Dr. Matthew J. McCarthy. His erudition was sparkling rather than sleek, and his manner and appearance were not too unlike those of the Professor Mecklin that I remember.

Part of our study covered the religious and racial prejudice that was rampant in America during the first quarter of this century, a poison that unhappily still lingers in our system. The Ku Klux Klan was revived in the South and the Middle West, crosses were burned, there were many instances of violence, and White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) held that the words "free and equal" in the Declaration of Independence did not apply to Negroes, immigrants, Jews, and Catholics.

In my lecture notes for this period I find:

"Feeling, not confined to s. and m-w. Widespread. In New Eng., e.g., many WASPs honestly belvd. that Caths. were storing guns in churches, getting ready to seize U.S."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

November 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44, -

Feature

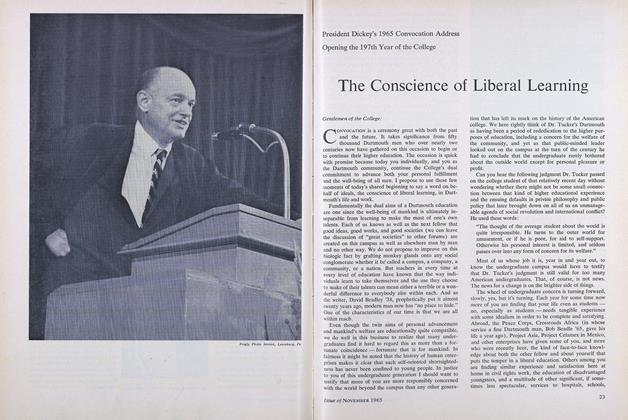

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

November 1965 -

Feature

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

November 1965 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

November 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

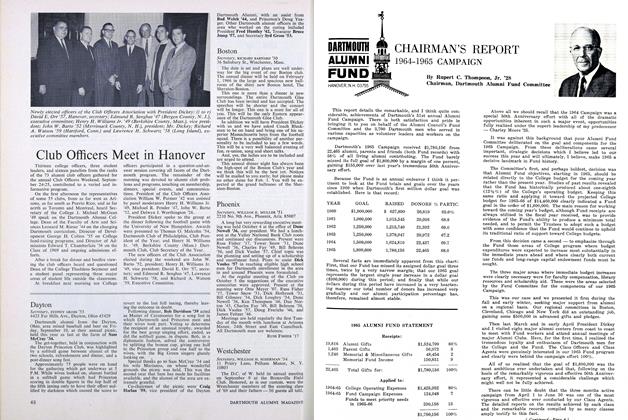

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

November 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

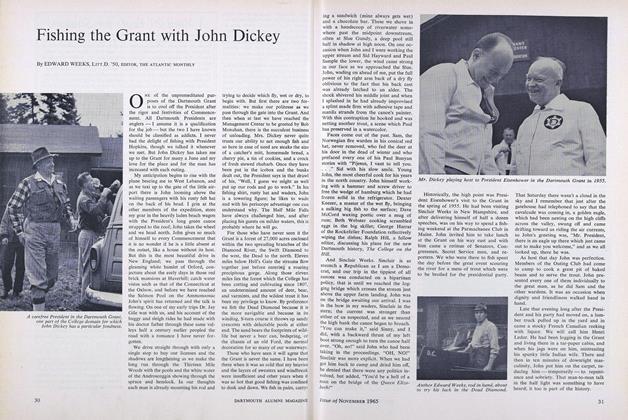

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

November 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50,

D. GORDON GRAHAM '28

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE TIE THAT BINDS A COLLEGE CLASS

January 1917 -

Article

ArticleBRYAN'S TALK INCREASES INTEREST IN EVOLUTION

March, 1924 -

Article

ArticleGREEK HONOR DECORATION BESTOWED ON PROF MESSER

March 1925 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in Politics

December 1932 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Authors

August 1944 -

Article

ArticleChicago

FEBRUARY 1970 By DAVID M. BURNER JR. '53