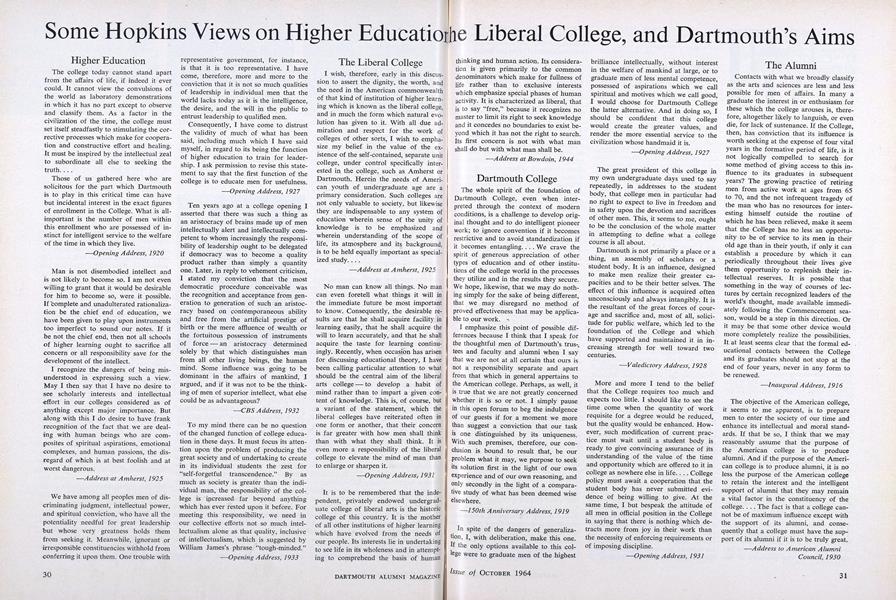

Higher Education

The college today cannot stand apart from the affairs of life, if indeed it ever could. It cannot view the convulsions of the world as laboratory demonstrations in which it has no part except to observe and classify them. As a factor in the civilization of the time, the college must set itself steadfastly to stimulating the corrective processes which make for cooperation and constructive effort and healing. It must be inspired by the intellectual zeal to subordinate all else to seeking the truth

Those of us gathered here who are solicitous for the part which Dartmouth is to play in this critical time can have but incidental interest in the exact figures of enrollment in the College. What is allimportant is the number of men within this enrollment who are possessed of instinct for intelligent service to the welfare of the time in which they live.

—Opening Address, 1920

Man is not disembodied intellect and is not likely to become so. I am not even willing to grant that it would be desirable for him to become so, were it possible. If complete and unadulterated rationalization be the chief end of education, we have been given to play upon instruments too imperfect to sound our notes. If it be not the chief end, then not all schools of higher learning ought to sacrifice all concern or all responsibility save for the development of the intellect.

I recognize the dangers of being misunderstood in expressing such a view. May I then say that I have no desire to see scholarly interests and intellectual effort in our colleges considered as of anything except major importance. But along with this I do desire to have frank recognition of the fact that we are dealing with human beings who are composites of spiritual aspirations, emotional complexes, and human passions, the disregard of which is at best foolish and at worst dangerous.

—Address at Amherst, 1925

We have among all peoples men of discriminating judgment, intellectual power, and spiritual conviction, who have all the potentiality needful for great leadership but whose very greatness holds them from seeking it. Meanwhile, ignorant or irresponsible constituencies withhold from conferring it upon them. One trouble with representative government, for instance, is that it is too representative. I have come, therefore, more and more to the conviction that it is not so much qualities of leadership in individual men that the world lacks today as it is the intelligence, the desire, and the will in the public to entrust leadership to qualified men.

Consequently, I have come to distrust the validity of much of what has been said, including much which I have said myself, in regard to its being the function of higher education to train for leadership. I ask permission to revise this statement to say that the first function of the college is to educate men for usefulness.

—Opening Address, 1927

Ten years ago at a college opening I asserted that there was such a thing as an aristocracy of brains made up of men intellectually alert and intellectually competent to whom increasingly the responsibility of leadership ought to be delegated if democracy was to become a quality product rather than simply a quantity one. Later, in reply to vehement criticism, I stated my conviction that the most democratic procedure conceivable was the recognition and acceptance from generation to generation of such an aristocracy based on contemporaneous ability and free from the artificial prestige of birth or the mere affluence of wealth or the fortuitous possession of instruments of force —an aristocracy determined solely by that which distinguishes man from all other living beings, the human mind. Some influence was going to be dominant in the affairs of mankind, I argued, and if it was not to be the thinking of men of superior intellect, what else could be as advantageous?

—CBS Address, 1932

To my mind there can be no question of the changed function of college education in these days. It must focus its attention upon the problem of producing the great society and of undertaking to create in its individual students the zest for "self-forgetful transcendence." By as much as society is greater than the individual man, the responsibility of the college is increased far beyond anything which has ever rested upon it before. For meeting this responsibility, we need in our collective efforts not so much intellectualism alone as that quality, inclusive of intellectualism, which is suggested by William James's phrase "tough-minded."

—Opening Address, 1933

The Liberal College

I wish, therefore, early in this discussion to assert the dignity, the worth, and the need in the American commonwealth of that kind of institution of higher learning which is known as the liberal college, and in much the form which natural evolution has given to it. With all due admiration and respect for the work of colleges of other sorts, I wish to emphasize my belief in the value of the existence of the self-contained, separate unit college, under control specifically interested in the college, such as Amherst or Dartmouth. Herein the needs of American youth of undergraduate age are a primary consideration. Such colleges are not only valuable to society, but likewise they are indispensable to any system of education wherein sense of the unity of knowledge is to be emphasized and wherein understanding of the scope of life, its atmosphere and its background, is to be held equally important as specialized study. ...

—Address at Amherst, 1925

No man can know all things. No man can even foretell what things it will in the immediate future be most important to know. Consequently, the desirable results are that he shall acquire facility in learning easily, that he shall acquire the will to learn accurately, and that he shall acquire the taste for learning continuingly. Recently, when occasion has arisen for discussing educational theory, I have been calling particular attention to what should be the central aim of the liberal arts college — to develop a habit of mind rather than to impart a given content of knowledge. This is, of course, but a variant of the statement, which the liberal colleges have reiterated often in one form or another, that their concern is far greater with how men shall think than with what they shall think. It is even more a responsibility of the liberal college to elevate the mind of man than to enlarge or sharpen it.

—Opening Address, 1931

It is to be remembered that the independent, privately endowed undergraduate college of liberal arts is the historic college of this country. It is the mother of all other institutions of higher learning which have evolved from the needs of our people. Its interests lie in undertaking to see life in its wholeness and in attempting to comprehend the basis of human thinking and human action. Its consideration is given primarily to the common denominators which make for fullness of life rather than to exclusive interests which emphasize special phases of human activity. It is characterized as liberal, that is to say "free," because it recognizes no master to limit its right to seek knowledge and it concedes no boundaries to exist beyond which it has not the right to search. Its first concern is not with what man shall do but with what man shall be.

—Address at Bowdoin, 1944

Dartmouth College

The whole spirit of the foundation of Dartmouth College, even when interpreted through the context of modern conditions, is a challenge to develop original thought and to do intelligent pioneer work; to ignore convention if it becomes restrictive and to avoid standardization if it becomes entangling. ... We crave the spirit of generous appreciation of other types of education and of other institutions of the college world in the processes they utilize and in the results they secure. We hope, likewise, that we may do nothing simply for the sake of being different, that we may disregard no method of proved effectiveness that may be applicable to our work.

I emphasize this point of possible differences because I think that I speak for the thoughtful men of Dartmouth's trustees and faculty and alumni when I say that we are not at all certain that ours is not a responsibility separate and apart from that which in general appertains to the American college. Perhaps, as well, it is true that we are not greatly concerned whether it is so or not. I simply pause in this open forum to beg the indulgence of our guests if for a moment we more than suggest a conviction that our task is one distinguished by its uniqueness. With such premises, therefore, our conclusion is bound to result that, be our problem what it may, we purpose to seek its solution first in the light of our own experience and of our own reasoning, and only secondly in the light of a comparative study of what has been deemed wise elsewhere.

—150th Anniversary Address, 1919

In spite of the dangers of generalization, I, with deliberation, make this one. If the only options available to this colfege were to graduate men of the highest brilliance intellectually, without interest in the welfare of mankind at large, or to graduate men of less mental competence, possessed of aspirations which we call spiritual and motives which we call good, I would choose for Dartmouth College the latter alternative. And in doing so, I should be confident that this college would create the greater values, and render the more essential service to the civilization whose handmaid it is.

—Opening Address, 1927

The great president of this college in my own undergraduate days used to say repeatedly, in addresses to the student body, that college men in particular had no right to expect to live in freedom and in safety upon the devotion and sacrifices of other men. This, it seems to me, ought to be the conclusion of the whole matter in attempting to define what a college course is all about.

Dartmouth is not primarily a place or a thing, an assembly of scholars or a student body. It is an influence, designed to make men realize their greater capacities and to be their better selves. The effect of this influence is acquired often unconsciously and always intangibly. It is the resultant of the great forces of courage and sacrifice and, most of all, solicitude for public welfare, which led to the foundation of the College and which have supported and maintained it in increasing strength for well toward two centuries.

—Valedictory Address, 1928

More and more I tend to the belief that the College requires too much and expects too little. I should like to see the time come when the quantity of work requisite for a degree would be reduced, but the quality would be enhanced. However, such modification of current practice must wait until a student body is ready to give convincing assurance of its understanding of the value of the time and opportunity which are offered to it in college as nowhere else in life. ... College policy must await a cooperation that the student body has never submitted evidence of being willing to give. At the same time, I but bespeak the attitude of all men in official position in the College in saying that there is nothing which detracts more from joy in their work than the necessity of enforcing requirements or of imposing discipline.

—Opening Address, 1931

The Alumni

Contacts with what we broadly classify as the arts and sciences are less and less possible for men of affairs. In many a graduate the interest in or enthusiasm for these which the college arouses is, therefore, altogether likely to languish, or even die, for lack of sustenance. If the College, then, has conviction that its influence is worth seeking at the expense of four vital years in the formative period of life, is it not logically compelled to search for some method of giving access to this influence to its graduates in subsequent years? The growing practice of retiring men from active work at ages from 65 to 70, and the not infrequent tragedy of the man who has no resources for interesting himself outside the routine of which he has been relieved, make it seem that the College has no less an opportunity to be of service to its men in their old age than in their youth, if only it can establish a procedure by which it can periodically throughout their lives give them opportunity to replenish their intellectual reserves. It is possible that something in the way of courses of lectures by certain recognized leaders of the world s thought, made available immediately following the Commencement season, would be a step in this direction. Or it may be that some other device would more completely realize the possibilities. It at least seems clear that the formal educational contacts between the College and its graduates should not stop at the end of four years, never in any form to be renewed.

—Inaugural Address, 1916

The objective of the American college, it seems to me apparent, is to prepare men to enter the society of our time and enhance its intellectual and moral standards. If that be so, I think that we may reasonably assume that the purpose of the American college is to produce alumni. And if the purpose of the American college is to produce alumni, it is no less the purpose of the American college to retain the interest and the intelligent support of alumni that they may remain a vital factor in the constituency of the college. ... The fact is that a college cannot be of maximum influence except with the support of its alumni, and consequently that a college must have the support of its alumni if it is to be truly great.

—Address to American AlumniCouncil, 1930

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

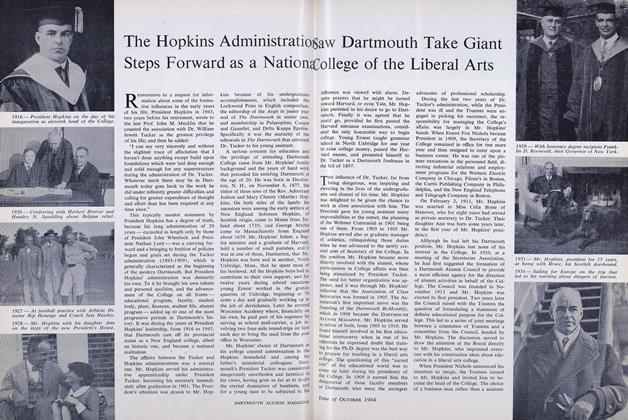

FeatureThe Hopkins Administration Steps Forward as a National

October 1964 -

Feature

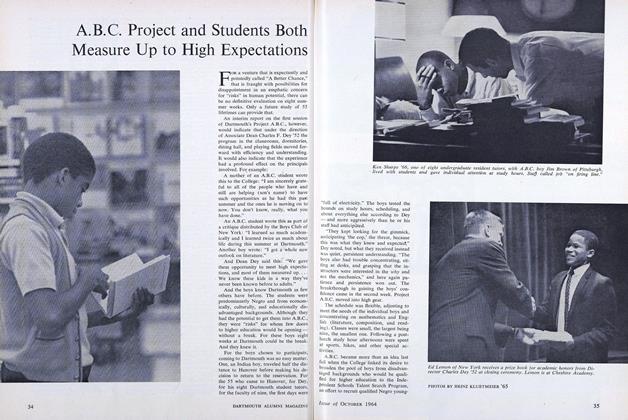

FeatureA.B.C. Project and Students Both Measure Up to High Expectations

October 1964 -

Feature

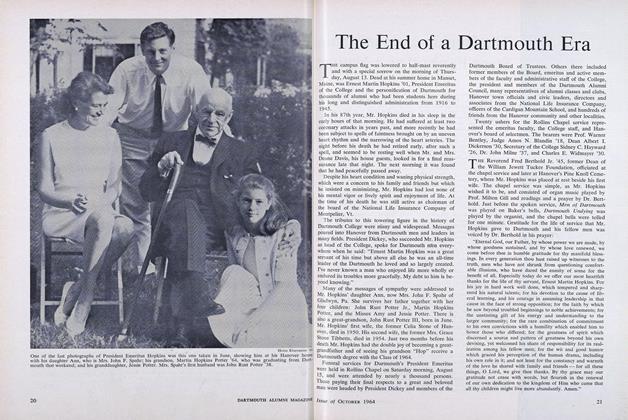

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

October 1964 -

Feature

Feature"This Considerate, Friendly Personality"

October 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

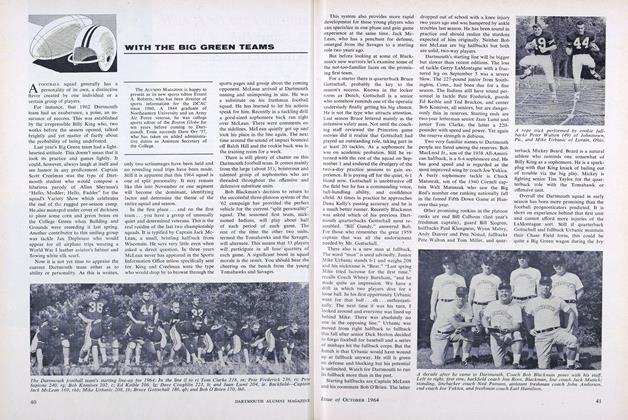

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1964

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDr. Hot's Thermal Therapy

JAN./FEB. 1979 By Bill Galvin -

Feature

FeatureIdea Entrepreneurs

April 2000 By JANE HODGES '92 -

Feature

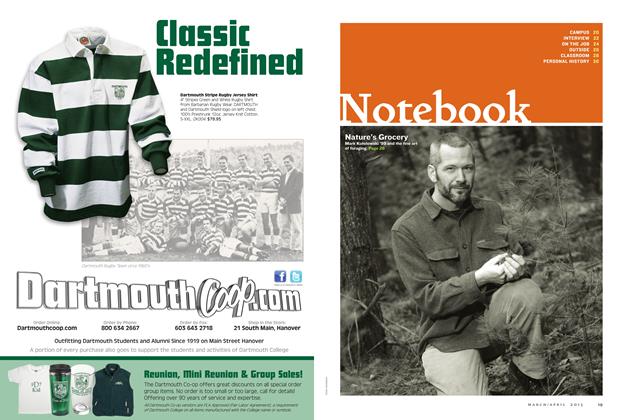

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2013 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureA Noble Pursuit

DECEMBER 1999 By Kevin Goldman ’99 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

DECEMBER 1965 By R.B.