Edited, with an introduction by WilcombE. Washburn '48. Garden City, NewYork: Doubleday & Co., 1964. 480 pp.$1.95.

As the traditional disciplines have become more and more specialized, paradoxically they have become increasingly interdependent. As the gaps have widened between them, new and hybrid specialties have developed to fill these gaps, viz. biochemistry, geophysics, psycholinguistics, and ethnohistory. The last-named is an attempt to bridge the gap between anthropology and history by utilizing the documents and methods of the historian to fill in ethnographic and chronological gaps in our knowledge of nonliterate peoples, a classic concern of the anthropologist.

Early anthropologists were well aware of the value of historical sources, but the newer breed, concerned more with "structure and function" and a search for "laws," have tended to become ahistorical, or even antihistorical. The subdiscipline of ethnohistory, really more of a method than a separate field of knowledge, attempts to correct this imbalance and now has its own professional society and journal. Interestingly enough, three of the leaders in this movement are Dartmouth men: William N. Fenton '30, John C. Ewers '31, both professional anthropologists, and Wilcomb E. Washburn '48, a historian.

The present volume, edited by Washburn, appears in the "Documents of American Civilization," a series whose aim is to make primary materials of American history available in paperback form. Washburn has brought together an amazingly interesting group of first-hand observations on the American Indian, gleaned from a wide variety of original sources and arranged under eight heads: (1) First Contact, (2) Personal Relations (including some observations on sex), (3) Dispossession, (4) Trade, (5) Missionaries, (6) War, (7) Governmental Relations, (8) Literature and Art. Included are such early observers as Christopher Columbus, John Rolfe, Father Hennepin, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, together with an on-the-scene description of "Mr. Wheelock's Indian School." As is so often the case with anthologies, many of the selections are so short that they are merely titillating. But if readers are titillated to read further in the field of ethnohistory one of Dr. Washburn's purposes will have been served.

Professor of Anthropology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureTHE COMPUTER REVOLUTION

November 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

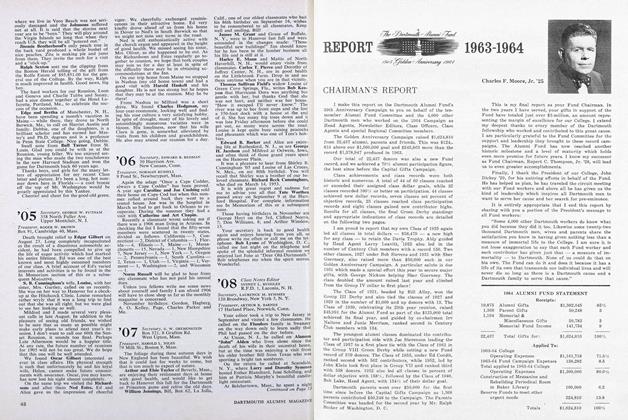

FeatureThe Darthmouth Alumni Fund REPORT 1963-1964 1915 Golden Anniversary 1964

November 1964 -

Feature

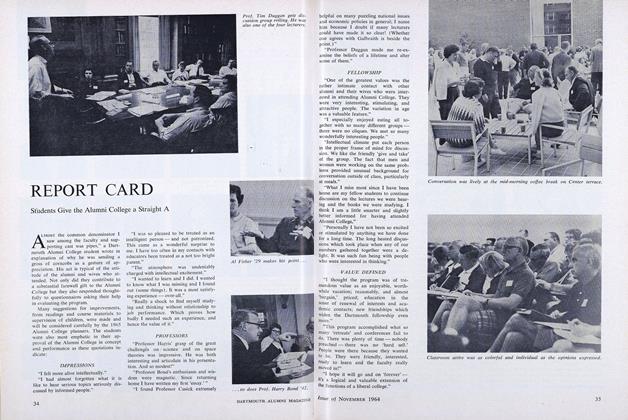

FeatureREPORT CARD

November 1964 -

Feature

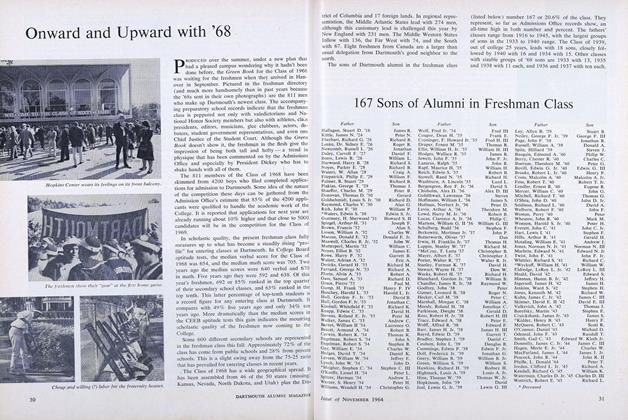

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

November 1964 -

Article

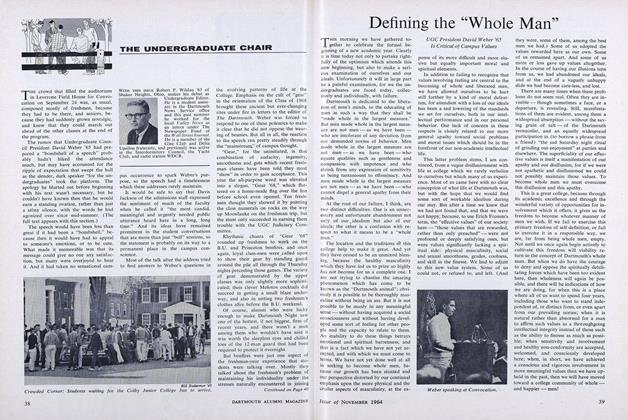

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65

ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25

-

Books

BooksTHE IROQUOIS EAGLE DANCE AN OFFSHOOT OF THE CALUMET DANCE.

February 1954 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN INDIAN AND WHITE RELATIONS TO

July 1957 By ROBERT A. MCKENNAN '25 -

Books

BooksTHE SIOUX, Life and Customs of a Warrior Society.

JULY 1964 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25 -

Books

BooksPARKER ON THE IROQUOIS. IROQUOIS USES OF MAIZE AND OTHER FOOD PLANTS. THE CODE OF HANDSOME LAKE, THE SENECA PROPHET. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE FIVE NATIONS.

JULY 1969 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25

Books

-

Books

BooksPlum in the Pudding

February 1977 By CHARLESG. BOLTE '41 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN CENTRAL AMERICA:

June 1946 By J. M. Arce -

Books

BooksTHE ENORMOUS EGG.

May 1956 By MAUDE D. FRENCH -

Books

BooksMAKE FREE: THE STORY OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD.

OCTOBER 1958 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Books

BooksTHE WINNING OF NICKEL, ITS GEOLOGY, MINING, AND EXTRACTIVE METALLURY.

JANUARY 1968 By ROBERT G. WOLFSON -

Books

BooksTHE SPADE AND THE BIBLE. W. W.

June 1934 By W. H. Wood