THE crowd that filled the auditorium in Leverone Field House for Convocation on September 24 was, as usual, composed mostly of freshmen, because they had to be there, and seniors, because they had suddenly grown nostalgic, and knew that they could march out ahead of the other classes at the end of the program.

The rumor that Undergraduate Council President David Weber '65 had prepared a "bombshell of a speech" probably hadn't hiked the attendance much, but may have accounted for the ripple of expectation that swept the hall as the slender, dark speaker "for the undergraduates" took the platform. The apology he blurted out before beginning with his text wasn't necessary, but he couldn't have known then that he would earn a standing ovation, rather than just a stony silence, with the words he had agonized over since mid-summer. (The full text appears with this section.)

The speech would have been less than great if it had been a "bombshell," because then it would have had to appeal to someone's emotions, or to be cute. What made it memorable was that its message could give no one any satisfaction, but many were overjoyed to hear it. And it had taken no sensational campus occurrence to spark Weber's purpose, so the speech had a timelessness which these addresses rarely maintain.

It would be safe to say that Davis Jackson of the admissions staff expressed the sentiment of much of the faculty when he called it "the most candid, meaningful and urgently needed public utterance heard here in a long, long time." And its ideas have remained prominent in the student conversations that are more than just "bull" sessions, so the statement is probably on its way to a permanent place in the campus conscience.

Most of the talk after the address tried to find answers to Weber's questions in the evolving patterns of life at the College. Emphasis on the cult of "gear" in the orientation of the Class of 1968 brought these ancient but ever-changing rites under fire in letters to the editor of The Dartmouth. Weber was forced to respond to one of these polemics to make it clear that he did not oppose the wearing of beanies. But all in all, the reaction to the speech ran pretty steadily through the "mainstrearal' of campus thought.

"Gear," for the uninitiated, is that combination of audacity, ingenuity, smoothness and guts which recent freshman classes have been told they must "show" in order to gain acceptance. This year the all-purpose word was elevated into a slogan, "Gear '68," which fluttered on a home-made flag over the Inn before school even opened. Ten freshmen thought they showed it by painting the class numerals on rocks on the way up Moosilauke on the freshman trip, but the stunt only succeeded in earning them trouble with the UGC Judiciary Committee.

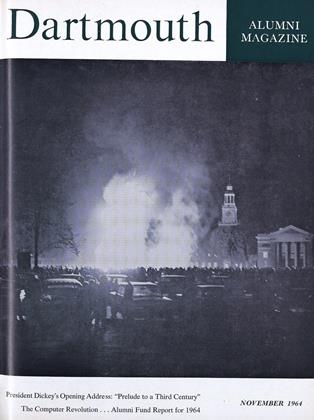

Rhythmic chants of "Gear '68" rounded up freshmen to work on the B.U. and Princeton bonfires, and once again, loyal class-men were called upon to show their gear by standing guard around the pile all through the Thursday nights preceding those games. The variety of gear demonstrated by the upper classes was only slightly more sophisticated; their clever Molotov cocktails did succeed in getting a small blaze underway, and also in setting two freshmen's clothes afire before the B.U. weekend.

Of course, alumni who were lucky enough to make Dartmouth Night saw one of the hottest, if not biggest, fires of recent years, and there wasn't a man among them who wouldn't have said it was worth the sleepless eyes and chilled toes of the 12-man guard that had been required to protect it overnight.

But bonfires were just one aspect of the freshman-year experience that students were talking over. Mostly they talked about the freshman's problem of maintaining his individuality under the stresses naturally encountered in joining a new community. He is faced with reestablishing a self-image as satisfying as the one he had in high school, but in much faster company. Dean Dickerson's famous parents' letters have, of course, rehashed this theme year after year with renewed eloquence.

But by the time one becomes a senior, and finds himself speaking to the same freshman misconceptions (that he himself held) for the third straight fall, he begins to wonder how these ideas get introduced in the first place. The old legends of drunken pranks that are retold on every American campus each year are trotted out again and some frail, big-eyed freshmen will be asking whether it is true that this happened at such and such a house at Dartmouth.

It would be difficult to believe that freshmen at any other institution could face as overwhelming an adjustment barrier as do these newcomers. Hanover is such a world unto itself that it often takes most of four years for students to regain the perspective on the outside world which they gave up when they first came here: on relationships with their elders, with women, and with real-life issues. Of the value systems open to them at that critical time, the gear cult (or Big Greenerism, as some have called it) is probably the easiest one to take up, and obviously some never outgrow it. By the time a man gets to be a senior, those first big encounters have receded far enough into the background that he is not likely to point to his own freshman experiences to recall the silly things that he thought and did back then. And so the system is perpetuated with only the slightest changes from year to year.

So if it seems to take most of four years to outgrow that first set of values, an alternative solution might be to try to inculcate different ones at the outset. To call into question the whole ancient tradition of beanies, rallies, and riots is to criticize a part of the Dartmouth experience unique, colorful, and somehow even sacred to every man who ever gave himself to it. But the broad patterns of change that have shaped the College in the past twenty years have all been in the general direction of changing it from a "small, colorful, fun kind of place," to use the words of one faculty wife, into an academic institution whose only aim is to be second to none in quality. In the scope of this change a big problem is going to be to retain the joy of living here, which stems also from the colorful traditions which are Dartmouth's alone. But if our business here is learning, and that business is getting tougher all the time, then how do we justify taking a freshman on his third night in town and asking him to yell his guts out for a Dartmouth that has yet done nothing to justify his loyalty, and in whose society he has yet to earn a place? Or by what value do we upperclassmen explain our perverse pleasure in watching hundreds of identically dressed peagreens come screaming down Webster Avenue - to let the air out of our tires? This fall more students were asking themselves whether this great leveling process is in keeping with the best of Dartmouth's ideals.

It was difficult for many to escape the conclusion that what Weber was talking about somehow began there. This year's Interdormitory Council orientation staff were not the only ones worried about these questions. Dean Seymour spoke to the boys on the Freshman Trip at Moosilauke on the importance of maintaining personal values under the stress of life at the College. Larry Hannah, chairman of Palaeopitus, and Steve Farrow, president of the IDC, struck similar chords in short talks at the first meeting of the class. So there was certainly plenty of intelligent concern being voiced about the subject, but it may also be increasingly difficult to rationalize some of the old customs.

THE fraternities, always of special interest in the fall, did find it necessary to change a couple of old customs this year. The Interfraternity Council moved on its own last May to tone down Sink Night by prohibiting party-visits among the houses. This ended a great tradition of beery fellowship renewed each year as the new pledges congratulated each other on their choices.

The record for this year's Sink Night showed that the measure reduced the number of injuries in Dick's House to less than a quarter of last year's total. And campus police failed to register a single complaint of property damage. The IFC and Dean Whitehair were happy to find no difficulty in enforcing the regulation, and from all reports "a good time was had by all" just the same.

The cash bar is also gone forever from Dartmouth fraternities after a local judge, a guest at a house cocktail party last spring, alerted liquor authorities to this violation of the state law, which no one would have believed was going unnoticed. The IFC spent a good deal of time in consultation with a lawyer in the hope of finding an easy solution to the problem. None was found and another one of those pledges of faith between the house leaders and the President of the College sealed the old-style 'tails party as a thing of the past.

The Sink Night resolution had been passed voluntarily by the houses to cancel out what was obviously an annual dose of poor publicity for the system, and it showed their responsiveness to those currents of public opinion which are consistent in their opposition to it. The hope was, and is, to counteract those forces by anticipating their criticisms. A certain undefined feeling among the presidents expected that the College would, in return, use its influence on the fraternities' behalf. Thus when they were confronted with the pledge which they had no alternative but to sign, grumblings of "what next?" could plainly be heard.

What next, indeed, for the fraternities seem to be an ever-present problem. Last year's efforts to legislate out discrimination in rush fell short of what some had hoped for. Neither the crusading by individual houses, such as Delta Upsilon, for reform within the national, nor this year's big, clean, and successful rush, are likely to have much effect in those quarters. The formation of a faculty-student committee to study all aspects of fraternity life sounded an ominous note when it was recalled that at Williams the seating of a similar committee was the first step toward the abolition of fraternities there. A preliminary, survey shows a majority of the Dartmouth committee to be confirmed fraternity men, but their study will obviously be no small challenge to the system for a re-definition of purpose in line with the College's increasingly sophisticated educational aims.

WITH THIS ISSUE Robert P. Wildau '65 of Shaker Heights, Ohio, makes his debut as Undergraduate Editor. He is a student assist- ant in the Dartmouth News Service office and this past summer he worked for the local Valley News as an intern under The Newspaper Fund of the Wall Street Journal. He is a member of the Glee Club and Delta Upsilon fraternity, and previously was active in the Interdormitory Council, the Yacht Club, and radio station WDCR.

Crowded Corner: Students waiting for the Colby Junior College bus to arrive.

For this cheerleader the Princetongame was chilling in several ways.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureTHE COMPUTER REVOLUTION

November 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

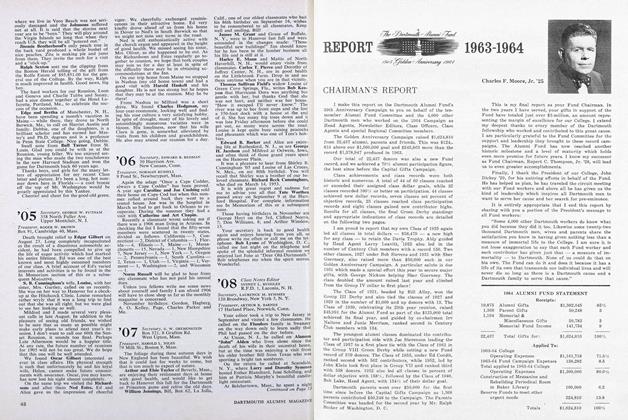

FeatureThe Darthmouth Alumni Fund REPORT 1963-1964 1915 Golden Anniversary 1964

November 1964 -

Feature

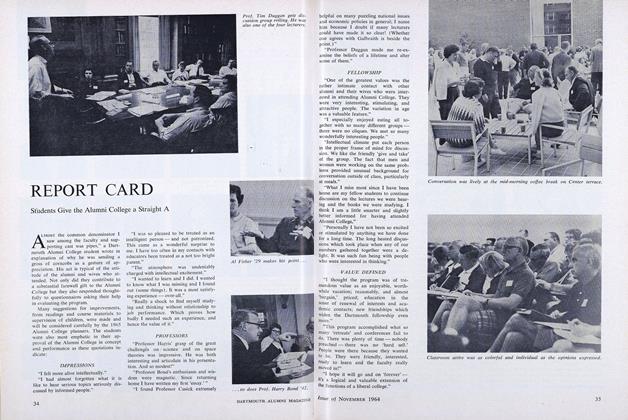

FeatureREPORT CARD

November 1964 -

Feature

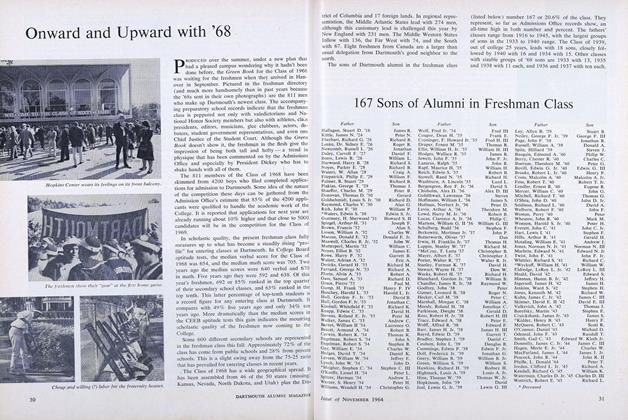

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

November 1964 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

November 1964 By ERNIE ROBERTS

BOB WILDAU '65

-

Article

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

DECEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65