President Dickey Addresses Students and Faculty to Open College's 196th Year

Men of the College and Colleagues of the Faculty:

WE gather in convocation to open the 196th year of Dartmouth. Unlike two recent, well-publicized national gatherings of the faithful this convocation is not dedicated to the proposition that the Nation will be saved or lost on November 3. Our purpose is somewhat more modest (I eschew the political diminutive - "moderate"); our purpose is also somewhat longer range. We aim to educate men rather than to nominate the next President of the United States. The possibility that these two purposes are not incompatible is, however, one of the tenets of our faith.

During the next six weeks there will be moments that remind us of Bernard Shaw's esteem for jungle beasts because they kill for food rather than politics or religion. When men contest for power, even the power that comes through the consent of the democratic process, they sometimes also get dangerously hungry. We who have a special stake in understanding these things, even as we participate in them, might make a modest contribution to the Nation by reminding ourselves as well as others that come what may in any November, so long as the democratic process functions no man plays this game for keeps.

If it seems only Ming that all 1964 convocations should have a theme, we might fashion ours from the merging echoes of Board Walk and Cow Palace. Let us continue ... to choose." This College has had considerable experience both with continuing and with choice. It is the high privilege of each of us to be the living proof of that continuity and the personal agency of Dartmouth's choices as she moves into the five final years of her second century. Let us look for a few minutes at this wonderful living thing we call "the College," venerable in years and service, and yet as young as the youngest here today and as full of fresh promise as the best among us.

Ten years ago the Trustees of the College committed Dartmouth to fifteen years of sustained rededication and refounding aimed, as I stated to the 1955 Convocation, "at bringing this institution to a running start of preeminent performance when it enters its third century on December 13, 1969. On that bicentennial birthday of George III's grant of corporate life, Dartmouth will celebrate her years as befits an enterprise of the higher learning by keeping pace with the future she helps create. The high promise of this bicentennial effort now rests not on a rhetoric of pride and aspiration, but on the deeds of the past ten years.

The foundation of this effort was an institutional purpose created by those whose lives and hopes were earlier built into this place. The plans and efforts of this rededication are grounded in the conviction that it is the job of the American undergraduate college to foster the growth of a man in all good directions. In truth, gentlemen, no mean task.

Among these good directions, the development of intellectual competence is "the first among equals. It is not that man lives by brains alone, but simply that the work of the mind is the prime business of higher learning. It is the one thing a college is best suited to do and therefore the thing it must do exceedingly well if it is to be a preeminent college. We seek to travel the way that leads a man toward a free and magnanimous mind as well as a sharp one. These qualities of mind are not synonymous, but neither are they natural enemies; they go together in a civilized man and in a free society that means to stay free. To this end Dartmouth, in rededication to her founding purpose, chose to continue her commitment to liberal learning. Her aim is to give every undergraduate some acquaintance with those varieties of learning a modern man needs to work his self-liberation in the course of a lifetime from the enthrallment of provincialism whether in time, place, circumstance, attitude or other condition of ignorance.

Let us not take for granted the part this sense of institutional purpose has played in Dartmouth's plans and their fulfillment. The aimless situation of undergraduate education in many centers of higher learning and the recent resurgence of concern with the development of an articulate "college purpose" in some of our foremost universities suggest that a first-rate college must be something more than merely a convenience of creature comforts catering to the personal purposes of scholar and student. That something more is the purpose of the place.

THE pride of this past decade is that high purposes have not stood naked of performance. All constituencies of the Dartmouth community and its far-flung fellowship have come forward with achievements that have done this College proud. Many of the most significant accomplishments, whether the primary work of Trustees, faculty, staff, students or alumni, have been joint ventures. All of our advances have required at least that kind of interdependent performance of duty by "water, fire, stick, dog and pig" described by the Mother Goose nursery rhyme as necessary for getting "over the stile and home tonight." Parenthetically, it should be noted that the dramatis personae of that bucolic parable in our particular grove of academe changed roles from performance to performance!

It is not for the actors in any performance to write their own review. Moreover, the full-bodied story of any period in the life of a complex, growing institution rarely gets told. It is a certain thing that relatively few of the daily achievements of faculty, students, and staff that created the Dartmouth of this period will be impaled on history's exclamation points. We can only know that every strengthening individual act and attitude in truth became part of the best that is Dartmouth today. My purpose in recalling a few of the developments of this period is not to write history but, first, to give the concreteness of performance to our sense of institutional purpose, and, secondly, to give each of us a merited measure of self-confidence for the tasks at hand and ahead.

The decade began in 1954 with the establishment of the Trustees Planning Committee. The T.P.C., as it is known, became the principal agency of the Board of Trustees for organizing and overseeing all long-range plans.

1954 was also notable for two salient actions advancing the concern of the College for the conscience of her men. On the initiative of the Trustees a new agency was created in the life and work of the College, the William Jewett Tucker Foundation, an independent endowment to further the enduring moral and spiritual concerns of the College in whatever ways may be appropriate to the day. The Tucker Foundation takes its purpose from one of the most fundamental resolves ever adopted by the Trustees of Dartmouth, and I daresay of any modern secular college. The Board formally affirmed that the College's "moral and spiritual purpose springs from a belief in the existence of good and evil, from faith in the ability of men to choose between them and from a sense of duty to advance the good." Men will ever debate the meaning of such words, but if the Tucker Foundation is well served it will be difficult here at Dartmouth ever to be indifferent to the timeless challenge of those words.

The other advance that year in the service of conscience was on the initiative of the students. By an extraordinary majority, after full discussion, the undergraduate body took a decision by referendum which six years later outlawed racial and religious discrimination from Dartmouth fraternities. Later, also on the initiative of student leaders, supported again by an extraordinary majority of the undergraduates, the faculty accepted the honor of Dartmouth men at face value and put each man under the eye of his own conscience in respect to academic honesty. Both of these hard-earned advances are today and for all tomorrows the sacred trust of every student who accepts the privilege of membership in this College.

In 1958 the faculty put into effect Dartmouth's new educational plan, the so-called three-course, three-term program with its basic objective of increasing independence in learning. Directly and indirectly this bold step significantly stimulated the intellectual work of the campus and opened up new opportunities for both teacher and student. The Committee on Educational Policy of the faculty is now actively examining opportunities for exploiting this advance and I hope that substantial proposals to this end will shortly be brought to the faculty for consideration.

A s the decade progressed the pace at which plans became programs moved up from that of a cross-country race to one of those modern miles where the starter's gun must be an automatic in order to get a warning shot fired before the final lap: interdisciplinary programs at both faculty and undergraduate levels in public affairs and human relations; an overseas study program for language majors; the faculty fellowship program to augment the sabbatical and research leave programs for the ongoing professional development of our teacher-scholar faculty, major new instructional and faculty facilities in the arts, the biological sciences, chemistry, drama, the languages, mathematics, medicine, music, and psychology; new student housing to accommodate an enrollment increase of 20% during the decade, about 15% of that increase was at the undergraduate level; the total refounding of the Dartmouth Medical School including the doubling of its enrollment, a new faculty and the expansion of faculty research from a 1954 level of under $10,000 to nearly 2 million dollars annually; the new Kellogg teaching Auditorium and the Dana Biomedical Library as joint-use facilities of the evolving Gilman Biomedical Center; a fundamental recasting of our approach to engineering education; the Nervi-designed Leverone Field House for year-around athletic use and large public affairs, along with new facilities for basketball, skiing, swimming and other sports; the Hopkins Center with all that it already means to all constituencies of the College as a pervasive liberal learning influence and the focal point of the campus community; the Comparative Studies project aimed at a more comprehensive and comparative approach to both scholarship and undergraduate education in the humanities and the social sciences; the Kiewit Computer Center and plans for bringing this powerful new aid of the human mind into the educational experience of at least three fourths of our undergraduates; new doctoral programs in mathematics, molecular biology and engineering; and finally a vital summer program which now embraces every purpose and most of the facilities" of the institution. This past summer this program demonstrated its capacity for significant educational pioneering with such proud firsts as the two-year Peace Corps Training Program, the A. B. C. project (A Better Chance) for educationally deprived youngsters, and the Alumni College. Each of these projects bore its own convincing witness to thrilling things about this College and its spirit that are better experienced than put into a speech.

THE wherewithal behind these advances largely came from the initiative and generosity of the Dartmouth family, particularly her dedicated alumni. In any listing of landmark achievements during this decade three deserve to stand out because without them others could not have been: The $17,000,000 Capital Gifts Campaign of 1959, a bequest program that added $16,000,000, and an annual Alumni Fund which in this 50th anniversary year brought to Dartmouth's cause 1,600,000 unrestricted dollars and the participation of 70 percent of all her alumni.

I shall forgo the temptation to give any over-all interpretation to the developments of this past decade, but it may be helpful to state several personal judgments. The most important of these is that the essential educational foundations of rededication: purpose, faculty, student body, facilities, and standards are now largely laid. The immediate future will be built on this foundation.

Dartmouth will continue to be dominantly an absolutely first-rate institution of liberal learning staffed by a faculty of teacher-scholars, preparing at least 80% of its undergraduate student body for advanced professional and academic study. Our historic graduate schools of medicine, engineering and business administration will continue to be selective, purposeful agencies of professional education with faculties committed to the kind of pioneering advanced scholarship appropriate to such enterprises.

The total size of the faculty and student body probably will not increase significantly in the next five years; a limited further expansion of graduate enrollments is likely. The construction program has been mainly completed. There will, of course, be important new projects from time to time, but the financing of most future facility needs ought to be manageable on a project by project basis.

The quality of a first-rate faculty and student body is always unfinished business. We will continue aggressively to seek and to develop the best in both. This will require major new financial resources for the compensation of the kind of a faculty we intend to have and keep and for the kind of scholarship program necessary to have a student body selected solely on its merit. Likewise, program developments in the academic departments and the Associated Schools, the libraries, the Hopkins Center, the Tucker Foundation, the D.C.A.C. and other areas will challenge the consideration of those both within and without the Dartmouth family who have the understanding, the financial power and the will decisively to advance the cause of education.

Experience to date with the new Ph.D. programs in mathematics and molecular biology indicates there is a sound basis of purpose, size and strength at Dartmouth for the development of her historic university functions, including selective doctoral programs. Our concern here is to choose those areas appropriate to our purposes and circumstance which clearly promise fresh distinction and added strength. We shall seek to develop such selective opportunities during the next five years in ways which will provide a significant example in the community of American higher education of an optimum relationship between selective professional and graduate programs and an enterprise committed to preeminent liberal learning.

As we enter the final phase of this bicentennial effort each of us, whatever his post of duty, is aware that if it were not for what has been done what remains might seem beyond our doing. Each constituency of the Dartmouth community now faces the kind of testing that comes only to those who are strong enough to choose to contest with themselves for a preeminent human performance.

If we of the faculty and staff can press the academic program forward during the next five years with the vigor and the disciplined sense of institutional purpose of these last five years I am confident that the war on ignorance will not produce at this advanced outpost the kind of plaintive inquiry recently received at the Washington headquarters of the war on poverty - "where do I go to surrender?"

If the student body, leader by leader, group by group, team by team, house by house, above all man by man, will do itself proud as one of the most highly powered, highly privileged communities of young men on the face of the earth, the best that is yet to be in American undergraduate education could be right here during the next five years.

If the Trustees and the alumni and all who sustain this enterprise of higher learning with generosity of mind, hand and benefaction will abide with the cause of Dartmouth even more, as well as ever more, they will not, I think, be disappointed in the return of satisfaction and pride they will know.

In confidence that such a contest with self is about as good an end as is permitted to any of us, I suggest that our approach to Dartmouth's Third Century be guided by Lord Dartmouth's motto Gaudet Tentamine Virtus - Valor rejoices in contest.

And now, men of Dartmouth, all this reminds us that however old and however great an institution is, it is always ultimately what its individuals are. As members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

Prior to delivering his main address at the Convocationexercises, President Dickey paid tribute to the late PresidentErnest Martin Hopkins, mainly by reading excerpts fromsome of Mr. Hopkins' public utterances. The opening portionof his memorial address follows:

Last month President-Emeritus Hopkins died in his 87th year. The tributes to his life and work which have been called forth by his death have enriched our memory of him. They also testify to the part such a life plays in the lives of countless others and in the causes to which it was dedicated.

Mr. Hopkins was a great servant of his time and in his time he served many causes in private affairs, public life, and in education. Above all else he was an all-time leader of the Dartmouth he loved and so largely created. He graduated from Dartmouth in the Class of 1901 and thereafter for some years served as a college officer, notably as an intimate assistant to President Tucker. After an interlude in business, he returned to the College in 1916 as the eleventh president in the Wheelock succession. On November 1, 1945 he handed to me as his successor the symbol of that trust, the silver punch bowl presented by Governor Wentworth, as the inscription states, to "the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock, D.D., and to his successors in that office."

During the 29 years of his presidency, Mr. Hopkins knew in larger measure than most men the challenges, the satisfactions, the troubles, the tragedies, and above all the joys that come to a capacious life lived magnanimously in responsibility and friendship. I have never been privileged to know a person who enjoyed the lot of being human more wholly or endured its grief more gracefully.

It is appropriate that on this occasion over which he presided so often we should remember Ernest Martin Hopkins not in the inadequacy of our own words, but through his own. I have selected a few brief excerpts from his public utterances which I hope may recall for some and suggest to others the transcending qualities of mind and spirit that fashioned the career of which we are the beneficiaries.

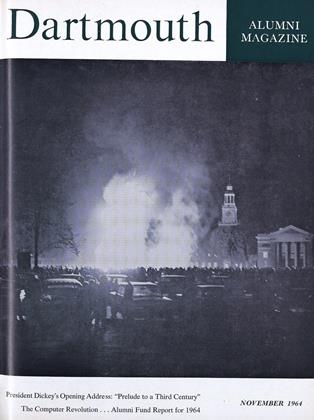

The President signing a '68 matriculation certificate.

President Dickey speaking to a group of freshmen stoppingat the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge during the Freshman Trip.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

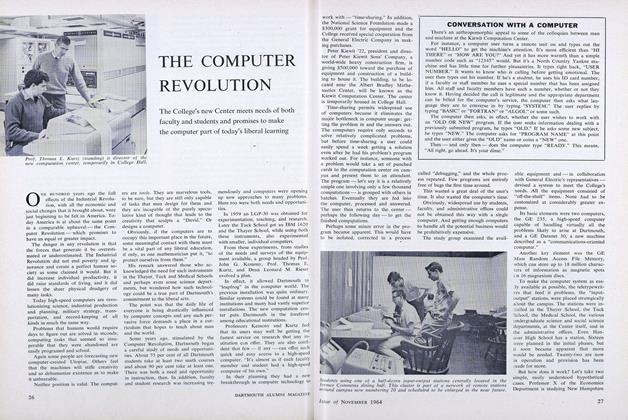

FeatureTHE COMPUTER REVOLUTION

November 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

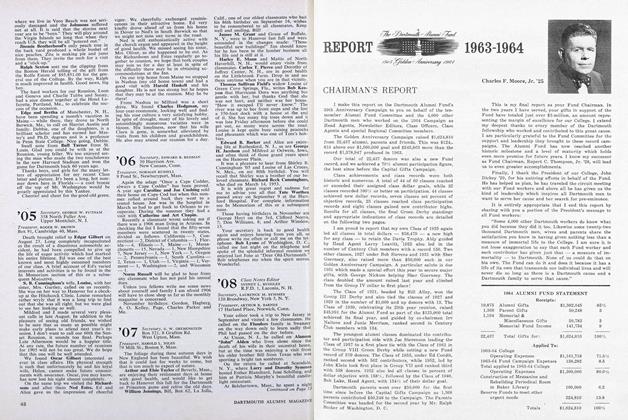

FeatureThe Darthmouth Alumni Fund REPORT 1963-1964 1915 Golden Anniversary 1964

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureREPORT CARD

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

November 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

November 1964 By ERNIE ROBERTS

Features

-

Feature

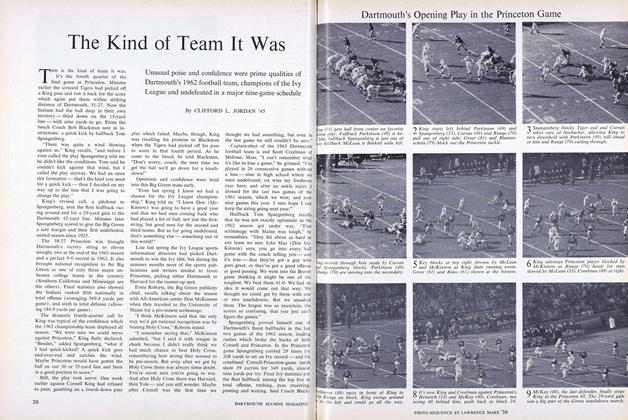

FeatureThe Kind of Team It Was

JANUARY 1963 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRonald Green

OCTOBER 1997 By Deborah Solomon -

Feature

FeatureA Story of Drama, Fierce Competition, Mom and Apple Pie

FEBRUARY 1989 By George Canizares -

Feature

FeatureUFOs Are Real!

APRIL 1999 By James Zug '91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Full Mind of Richard Eberhart

DECEMBER 1997 By Jay Parini -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99