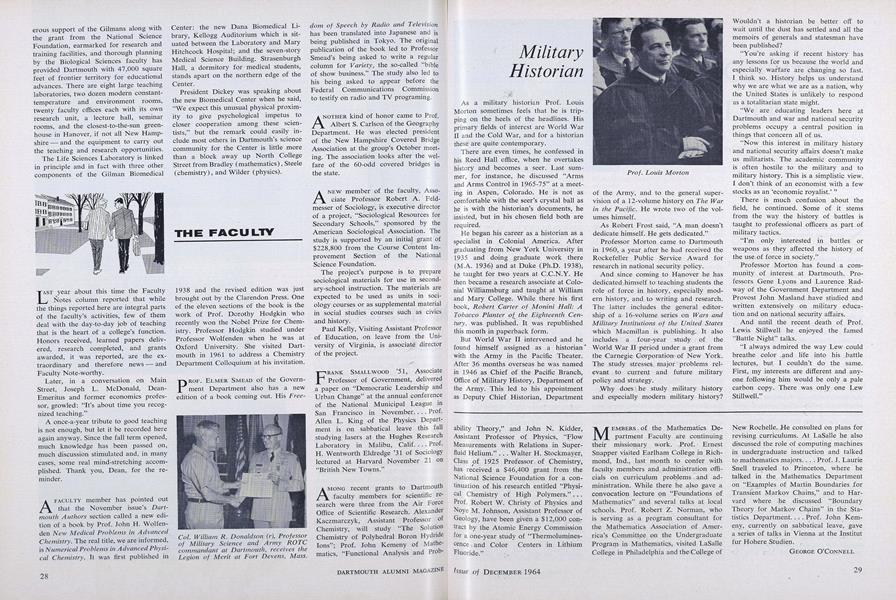

As a military historian Prof. Louis Morton sometimes feels that he is tripping on the heels of the headlines. His primary fields of interest are World War II and the Cold War, and for a historian these are quite contemporary.

There are even times, he confessed in his Reed Hall office, when he overtakes history and becomes a seer. Last summer, for instance, he discussed "Arms and Arms Control in 1965-75" at a meeting in Aspen, Colorado. He is not as comfortable with the seer's crystal ball as he is with the historian's documents, he insisted, but in his chosen field both are required.

He began his career as a historian as a specialist in Colonial America. After graduating from New York University in 1935 and doing graduate work there (M.A. 1936) and at Duke (Ph.D. 1938), he taught for two years at C.C.N.Y. He then became a research associate at Colo- nial Williamsburg and taught at William and Mary College. While there his first book, Robert Carter of Monini Hall: ATobacco Planter of the Eighteenth Cen-tury, was published. It was republished this month in paperback form.

But World War II intervened and he found himself assigned as a historian with the Army in the Pacific Theater. After 36 months overseas he was named in 1946 as Chief of the Pacific Branch, Office of Military History, Department of the Army. This led to his appointment as Deputy Chief Historian, Department of the Army, and to the general supervision of a 12-volume history on The Warin the Pacific. He wrote two of the volumes himself.

As Robert Frost said, "A man doesn't dedicate himself. He gets dedicated."

Professor Morton came to Dartmouth in 1960, a year after he had received the Rockefeller Public Service Award for research in national security policy.

And since coming to Hanover he has dedicated,himself to teaching students the role of force in history, especially modern history, and to writing and research. The latter includes the general editorship of a 16-volume series on Wars andMilitary Institutions of the United States which Macmillan is publishing. It also includes a four-year study of the World War II period under a grant from the Carnegie, Corporation' of New York. The study stresses. major problems relevant to current and future military policy and strategy.

Why does1 he study military history and especially modern military history? Wouldn't a historian be better off to wait until the dust has settled and all the memoirs of generals and statesman have been published?

"You're asking if recent history has any lessons for us because the world and especially warfare are changing so fast. I think so. History helps us understand why we are what we are as a nation, why the United States is unlikely to respond as a totalitarian state might.

"We are educating leaders here at Dartmouth and war and national security problems occupy a central position in things that concern all of us.

"Now this interest in military history and national security affairs doesn't make us militarists. The academic community is often hostile to the military and to military history. This is a simplistic view. I don't think of an economist with a few stocks as an 'economic royalist.' "

There is much confusion about the field, he continued. Some of it stems from the way the history of battles is taught to professional officers as part of military tactics.

"I'm only interested in battles or weapons as they affected the history of the use of force in society."

Professor Morton has found . a community of interest at Dartmouth. Professors Gene Lyons and Laurence Radway of the Government Department and Provost John Masland have studied and written extensively on military education and on national security affairs.

And until the recent death of Prof. Lewis Stillwell he enjoyed the famed "Battle Night" talks.

"I always admired the way Lew could breathe color and life into his battle lectures, but I couldn't do the same. First, my interests are different and anyone following him would be only a pale carbon copy. There was only one Lew Stillwell."

Prof. Louis Morton

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureVANISHING ABSOLUTES

December 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

December 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Feature

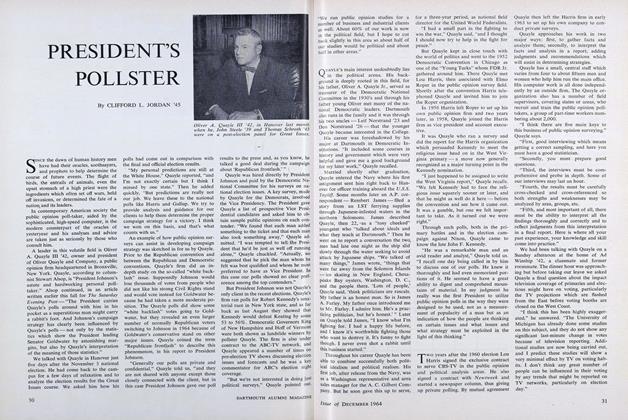

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

December 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

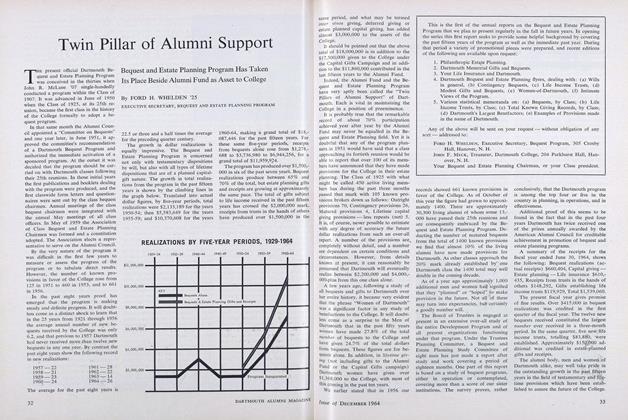

FeatureTwin Pillar of Alumni Support

December 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

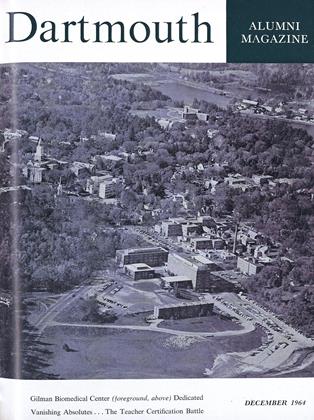

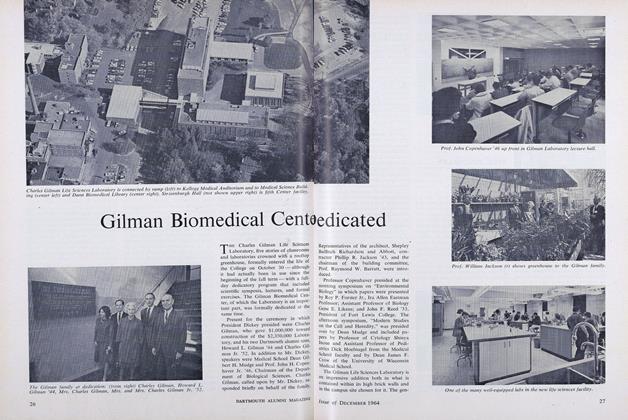

FeatureGilman Biomedical Centedicated

December 1964 -

Article

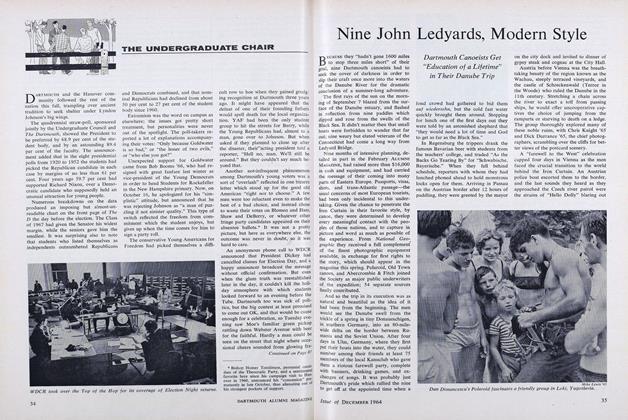

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

December 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65