TENNESSEE WESLEYAN COLLEGE

URGED on by some innate power, Samuel Lorenzo Knapp (Dartmouth 1804), whatever the condition of his private life, gave himself freely to the task of "puffing" American Culture at a time when to recognize the existence of such an idea was startlingly new. Knapp spent the last twenty years of his life writing, speaking, even haranguing the people from the District of Columbia to Massachusetts on the importance of American studies, and for all his efforts he has been remembered only vaguely as a biographer who, because he often stood so close to his subjects, was sometimes historically wrong or biased. His fellow townsman of Newburyport, Massachusetts, the late John P. Marquand, appeared reluctant to be appreciative of his work even though his last book, Timothy Dexter Revisited (Little, Brown, 1960), owed approximately one-fifth of its contents to the first book-length study of Dexter, which Knapp had written in the last year of his life.

A product of Phillips Exeter, Dartmouth College, and Theophilus Parsons' law office, where John Quincy Adams had earlier read law, Knapp tried repeatedly to live by the profession for which he had trained, beginning in 1809 when he opened an office in Newburyport. In 1812 he became a member of the Massachusetts State Legislature, and at the same time was a regimental colonel of the state militia, prepared at the time of the war with Great Britain to defend the Massachusetts coast. In the meantime he was gaining a reputation as an orator and as a Mason and was becoming a familiar figure at local functions where spread-eagle oratory was in demand. His Fourth of July Oration in 1810 was the first in the long series of published speeches to which he added regularly all through his life. In spite of all this success, his law practice seems to have been a failure. At any rate, he was not able to make it support the resultant family of his marriage in 1814, for by 1816 he was in jail for his debts.

In prison he turned for the first time to a serious attempt at writing and found this to be his forte. Extracts from theJournal of Marshall Soult, a pseudojournal describing a tour of New England, especially Newburyport, was successful enough to provide the money for the deliverance of its author from his cell. He immediately moved to Boston where he was associated for a time with Daniel Webster in his law work.

But Knapp had tasted of the fruit. The literary success of 1817 was followed in 1818 by Extracts from a Journal ofTravels in North America ... By Ali Bey, a bold continuation of the popular Arabian travels of a European writer. In Boston he very soon became involved with pugnacious J. T. Buckingham and assisted him in founding and operating the New England Galaxy and MasonicMagazine during its first year, Knapp made good use of their friendship when he began to work on BiographicalSketches of Eminent Lawyers, Statesmen,and Men of Letters, to appear in 1821. In a letter to Royall Tyler, early in 1820, Buckingham expresses his belief that the proposed volume would "do honor to Knapp and his country" and solicited Tyler's assistance in gathering material for the sketch on loseph Dennie, editor of The Port Folio in Philadelphia.

AT that early date Knapp had devised a plan to expedite his search for material. In the Boston Public Library is a printed letter such as Knapp dated, signed, and mailed out, perhaps by the score, in an effort to secure information on his subjects. This copy, the only known sample, dated January 1, 1820, explained what he intended to do in his book. He deplored the "scanty records" of the American past and hoped to snatch from oblivion as many names as possible:

"To this end I ask you to lend your assistance in collecting any facts of distinguished men who have resided in your part of the country, which may assist me in giving a narrative of their lives, or in developing any traits of their characters. By complying with this request, and sending me as soon as may be convenient what facts you may collect you will add something to the common stock of knowledge and confer a favour on me."

He—turned to newspaper writing in 1824, becoming the editor of the Boston Commercial Gazette. In that same year he delivered the Phi Beta Kappa Address at Dartmouth College. In lune 1825, still editing the Commercial Gazette, he founded the Boston Monthly Magazine. Although other subjects were discussed, generally speaking the scope of this publication was Americana, and he wrote in his prospectus:

"We shall not confine ourselves to any particular field of literature or philosophy. . . . We intend to make our biographical department as valuable as we can. The antiquarian shall find an ample space in our numbers for his researches and reminiscenses... We shall not be unmindful of the numerous institutions and societies now flourishing in our country;—their origin, growth and value, shall be fairly discussed."

American genius as reflected in patent office records, literature, folklore, politics, society, and individual lives was the object of his study. Partially as a reward for his sketch of Bishop Cheverus's life, published in the first issue of this magazine, he was given a LL.D. from the University of Paris, France. Before giving up this financially unprofitable magazine to move to the national capital to work for Peter Force's National Journal, he issued an appeal to Americans to work toward complete agricultural, industrial, and literary independence, which he believed to be needed in the new psychic climate of the country.

In August 1826 he and his friend Daniel Webster gave the official Boston eulogies for John Adams and Jefferson, with President John Quincy Adams in attendance. Later in Washington, where he had gone apparently at the invitation of the President, Knapp moved in high places and, as seen in his scattered and fragmentary correspondence of this period, was much concerned with politics. The National Journal in those hectic days was a decided force in the Adams-Jackson political struggle, having in the previous Presidential campaign played a major role in the attempt to blackguard Mrs. Jackson. When the old order gave way to Jacksonian Democracy in 1829 and Massachusetts influence waned in the capital city, Knapp moved to New York.

There he completed for publication his Lectures on American Literature, WithRemarks on Some Passages of AmericanHistory (1829), highly significant because it was the first serious attempt at writing a full history of American literature and because it sounded clearly his nationalistic call for American history — in fact, American studies — to be taught in schools. He believed that by 1829 the "American Mind" had been "set" as a distinct entity and that the time had come to "speak freely and justly of ourselves, and honestly strive to place our claims to national distinction on the broad basis of well authenticated historical facts." The Lectures he "offered as the opening argument of junior counsel, the great cause instituted to establish the claims of the United States to that intellectual, literary, and scientifick eminence, which we say she deserves to have." He saw himself as simply the beginning: "I have attempted but little more than to state my points, name the authorities, and then have left the whole field for those abler advocates who may follow me."

In the Preface he spoke directly to teachers:

"Be it your duty ... to make your students acquainted with the minutest portions of their country's history Guardians of a nation's morals, framers of intellectual greatness, show to your charges, in proper lights, the varied talents of your country in every age of her history; and inscribe her glories of mind, and heart, and deed, as with a sun-beam, upon their memories."

A study of American Culture was his aim. As the lectures developed, it became apparent that his definition of literature was so broad that it included the written and spoken word, art, and, in fact, the national spirit, no matter how it might be expressed.

OF all Knapp's work, the Lectures, has received the kindest attention by recent critics - though that has been scant. On chronological Americana lists it is usually given as the first history of American Literature. Howard Mumford Jones in The Theory of American Literature (1948) gave it high recognition. One attempt to boost the Lectures was mud. died when H. L. Mencken in the fourth edition of The American Language (1937) quoted erroneously from it. One of American Literature's greatest historians, Fred Lewis Pattee '88, writing in the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE in 1936, explained that its importance rested on the fact that Knapp, for the first time, studied American Literature's "fountain heads in American history and in the American philosophical evolutions and worked out a plan of study greatly suggestive to later workers."

But the Lectures dealt mainly with the American past, and Knapp hastened to supplement that volume with Sketches ofPublic Character, in which he devoted a considerable amount of space to his contemporaries who had been deliberately omitted from the Lectures because of lack of space. In this collection of American biographies appear such people as William Wirt, Edward Everett, Mrs. Lydia Signourney, Mrs. Sarah J. Hale, and John Vanderlyn, whose portrait of Knapp hangs in the Baker Library of Dartmouth College.

Always he was a collector of Americana. As early as 1814 his interest had won his election to the membership of the American Antiquarian Society. Unfortunately his private collection did not remain intact, but its extent and value can be judged by references to it in his writings. He treasured old documents, whatever their origin. The almanac which Samuel Sewall used as a daybook in 1718, now in the possession of the Massachusetts Historical Society, according to the Lectures, belonged to him in 1829. His library of early American history would have been very nearly definitive in his time.

As the last years of his life moved along, Knapp was writing faster and faster and experimenting with new literary ideas. He wrote a novel, PolishChiefs (1832), based on the American Revolution, and produced two volumes of weak short pieces, Tales of the Garden ofKoscuszko (1834) and The Bachelorsand Other Tales, Founded on AmericanIncidents and Characters (1836). There is evidence which indicates that he had a part in the writing of Miriam Coffin (1834), one of Melville's sources for Moby Dick.

In 1834 he preceded Sarah J. Hale and Rufus w. Griswold by several years with his Female Biography, a biographical dictionary not unlike their later productions. Although he included women of all nationalises, his important contribution was his sketches of the lives of the American women whom he had known and consequently could write about with personal knowledge. This book went through four editions before 1846.

PROBABLY his most ambitious undertaking was the Library of American History: A Reprint of Standard Works:Connected by Editorial Remarks,Abounding with Copious Notes, Biographical Sketches and MiscellaneousMatter, Intended To Give the Reader aFull View of American History, Colonialand National. Originally published in installments as The American Library:Being a Weekly Publication Devoted toAmerican History, Knapp gave it the longer title when he brought it out in two impressive tomes in 1835. The Picturesque Beauties of the Hudson River andIts Vicinity, two volumes illustrated with original steel engravings, he produced in 1835-36. During the next year Knapp prepared Advice on the Pursuits of Literature, intended to serve as a literature textbook; its success was such that a second edition was needed in 1841.

In the meantime, since the 1820's he had written individual biographical studies of many people who had been important in American life - such personages as Lafayette, DeWitt Clinton, Susanna Rowson, Daniel Webster, Thomas Eddy, Aaron Burr, and Andrew Jackson. The Life of Timothy Dexter: EmbracingSketches of the Eccentric Characters thatComposed His Association in 1838 was his last work. While little has been said about Knapp during the last century, much of what has been said has been devoted to calling these biographies unreliable hack work. True, they do not meet the standards of current Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies, but they are valuable as source material for such works. Knapp wrote about his contemporaries, selecting and shading his words to present the people in the light in which he saw them. At times he lifted whole sections from sketches which other people had written, frequently specifically for use in his books. In his own writing, he was apt to let febrile oratorical phrases overshadow objective discussion, and to the uncritical eye bombast sometimes concealed omissions in his logic and knowledge. On the other hand, he utilized personal recollections and homey ancedotes which are no longer available, for he was a speaking acquaintance of many of his subjects. For example, he had been with Lafayette during that historic giant's visit to Boston in 1824. He had supped tea with Mrs. Rowson, and his posthumous preface to Charlotte's Daughter (1828) is the basis for the modern studies of this early American novelist. He had been at the bar of law with Webster, and A Memoirof the Life of Daniel Webster (1831) was the first approved biography of the statesman. His magpie.-ish collection of material on Thomas Eddy (1834) is the only extensive biographical study of the prison reformer. Are his biographies then so worthless? The several bibliographical entries citing Knapp's work in the Dictionary of American Biography suggest that his influence in this field is greater than might be casually assumed.

THIS was by no means the full range of Knapp's work. He wrote loyally for the magazines of his time, contributing to many of the major American periodicals. As a magazinist he was in such demand that he found it necessary at times to turn down commissions. When he died in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, on July 8, 1838, the editor of The Knicker-bocker lamented that the American literary scene could ill afford to lose Colonel Knapp's pen, the military title a holdover from his service in the War of 1812.

In the years immediately following his death, new editions of old works continued to come out. American Biography (1833), a collection of his best sketches, became in 1850 the third volume of TheTreasury of Knowledge and Library ofReference. During this century his 1830 Forefather's Day Oration before the New England Society in New York has been reprinted. The Lectures has been reissued as American Cultural History, 1607-1829 (Scholar's Facsimiles and Reprints, 1961), with a name, title, and subject index.

Aside from biographical sketches which have source value and certain sections of the Lectures, Knapp's individual writings may not be vitally important. But the corpus is extremely valuable because it is the work of his "American Mind." It was a mind which believed in its past and looked eagerly to the future in a milieu of its own making. Virtually everything that Knapp wrote was a part of his "opening argument" in behalf of American Culture. Instead of rejecting his work as has been the fashion for many years, we should be charmed by the noise of the federal eagle as it flaps its great wings and sounds its chauvinistic screams throughout the pages, proclaiming Knapp's early nineteenth-century message of the development of an American Culture.

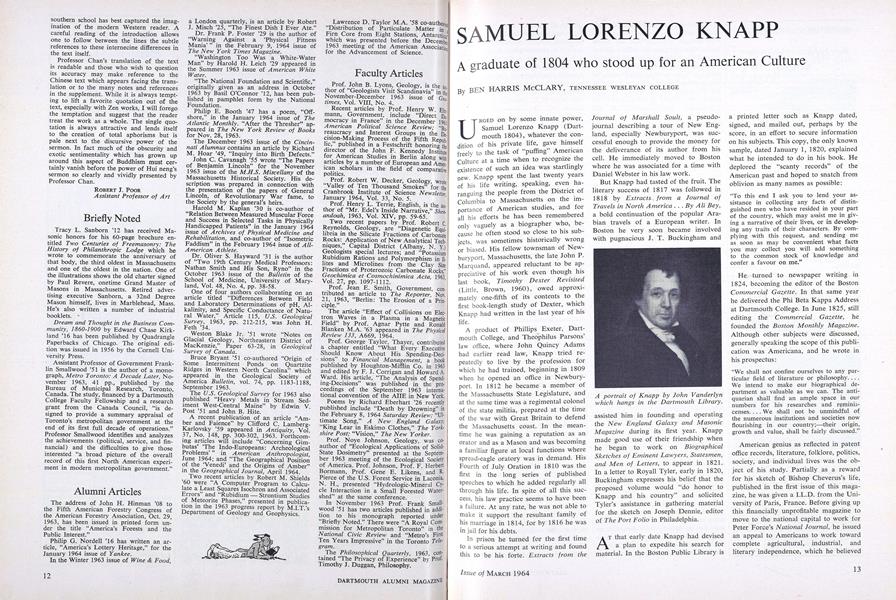

A portrait of Knapp by John Vanderlynwhich hangs in the Dartmouth Library.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

March 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

March 1964 -

Feature

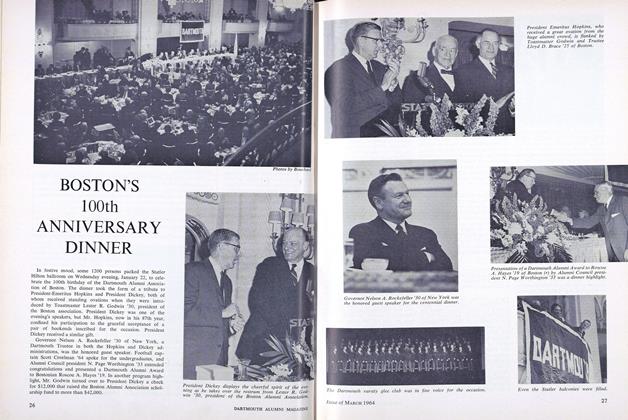

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1964 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER