A MAJOR report, The College andWorld Affairs, now attracting wide attention in the educational world, has special Dartmouth interest because of the participation of President Dickey and Provost John W. Masland in the two-year study that is summarized in the printed report released last month.

The ten-man committee, headed by President John W. Nason of Carleton College, focused its attention on a vital problem of liberal education - "that created by the increasing need for sensitive awareness of the cultural pluralism of our day and by an ever more complex and swiftly changing world." The report finds U. S. colleges failing in their responsibility to prepare Americans for world leadership and calls for a clear and unequivocal institutional commitment to "the international dimension of liberal education." It recommends far-reaching changes in the curriculum of the liberal arts college and other undergraduate programs, and urges that greater financial resources, from outside sources and from the institutions themselves, be devoted to the new strategy of liberal learning that the contemporary world calls for.

In addition to Presidents Nason and Dickey, four other college presidents were members of the study group: Hugh Borton of Haverford College, Douglas M. Knight of Duke University, J. Ralph Murray of Elmira College, and C. Easton Rothwell of Mills College. Also serving on the committee brought together and financed by a grant from the Edward W. Hazen Foundation were Professor Masland of Dartmouth; Robert F. Byrnes, Professor of History at Indiana University; John B. Howard, director of the Ford Foundation's international training and research program; and William W. Marvel, president of Education and World Affairs. Dr. George M. Beckmann of the International Training and Research Program, Ford Foundation, served as study director, and Prof. John M. Thompson of Indiana University worked with the committee as a staff member.

The main body of the report on TheCollege and World Affairs consists of three sections: Liberal Learning in a Changing World, Strengthening the Faculty and Teaching Resources, and De- veloping the Educational Program (Dartmouth's new Comparative Studies Center is cited as one of the significant developments in this area). In its concluding section, summarizing the committee's thinking, the report says:

"Any serious fundamental change in the intellectual outlook of human society," Whitehead once wrote, "must necessarily be followed by an educational revolution." This report develops the propositions that fundamental and far-reaching changes in this century necessitate a new intellectual outlook and that this profoundly different outlook requires a new strategy of liberal learning.

We have concentrated primarily on those changes which are reflected in the new awareness of the inter-relationships of societies and cultures and on the ways and means of effecting a significant reorientation in education at the undergraduate level. We recognize that the resulting problems of readjustment are not the only problems with which modern education must cope. Nevertheless, we believe the revolution in education required by the conditions of the modern world is essential to survival and implicit in the nature of liberal learning.

The contemporary world requires of its educated citizens a breadth of outlook and a degree of sensitivity to other cultures unlike any required in the previous history of mankind. This requirement coincides with the universality of viewpoint characteristic of the liberally educated individual. The new and still changing role of the United States in world affairs has gradually come to be recognized, though we have not learned how to prepare ourselves adequately for fulfilling our new responsibility. To do so we must, in addition to the more obvious aspects of international relations, become more sensitive to the many diverse cultures which reflect the myriad manifestations of the human spirit. With the multiplication of new nations, these varying sets of beliefs and values and instinctive habits of behavior become more critical, and an understanding of them becomes central to the development of constructive attitudes and wise policy. Indeed, we must go even farther and recognize the interplay of one culture with another. None is static, least of all our own. To understand ourselves we must be able to understand both how- we differ in outlook and value system from other peoples, and how our own complex network of social, economic, political, and intellectual factors evolved from the interaction of forces within our society and forces acting on it from without.

It is therefore our thesis that liberal learning must include study of the varying and constantly changing cultural con- ditions of men. We believe that the similarities and contrasts thus revealed will illumine the nature of our own society. To be effective the educational revolution involved in this approach must permeate all undergraduate education. We have here considered it primarily in relation to the liberal arts college, whether independent or part of a university, for it is here that liberal learning is either the vital heart of the matter or our colleges will be increasingly purposeless in the most fundamental sense. The spirit of liberal learning, however, must imbue all significant education; increasingly it is needed as a part of the undergraduate programs in business, agriculture, engineering, nursing, teaching, and other professional or semi-professional fields.

We are proposing that those, responsible for undergraduate education give serious and sustained thought to how they can best incorporate into undergraduate life and work significant experience from cultures other than the familiar ones of Western Europe and North America. This procedure would lead to the enrichment of courses normally elected by large numbers of freshmen and sophomores. More specialized courses must be made available to upperclass students. We leave it to individual institutions to determine the advisability of establishing area majors and special language instruction. There is no one orthodox pattern of instruction or organization. Different institutions will want to follow different methods, and the resulting diversity and experimentation will be helpful to all.

The central problem is our sense of purpose; resources come next. We urge that every possible step be taken both to clarify the sense of institutional commitment and to strengthen faculty competence. The latter requires both the broadening of existing faculty interests, and the recruitment of new faculty with special talents. Library resources and teaching aids are in short supply, but more useful new materials have become available in the last decade than is generally realized. Students must be encouraged to supplement on-campus study with experience abroad. Opportunities for foreign study have existed for some time and additional programs are springing up in many quarters.

Colleges can make limited resources go farther by cooperating with other institutions: sharing faculty and library resources, developing programs such as overseas study jointly, working out a division of labor in foreign area and language studies, and taking advantage of the experience and resources of nearby universities.

Two prerequisites are indispensable for a successful program. One is financial resources. The major benefactors of Ameri- can higher education have a great opportunity to serve both a great national need and the cause of liberal education. Support from foundations, corporations, the government, and individual donors will facilitate and improve the quality of resulting programs. On the other hand, much can be done without the infusion of new money. Progress will come more slowly. Programs will be less ambitious. Quality may suffer. Nevertheless, money can be diverted from present commitments, and current sources of funds can be tapped for new ventures.

We repeat that what is most needed is the second prerequisite, namely a clear and unequivocal institutional commitment to what in shorthand fashion we have called the international studies dimension of liberal education. It is too late merely to play with new ideas. The changes which are now called for cannot be accomplished in a halfhearted way. They require recognition on the part of both faculty and students that the new international dimension is not an extra, but an integral part of the educational program. They require conviction about the ends to be realized, a readiness for genuine innovation, and the vision to see that the revolution in education is in the last analysis a continuation and realization of what liberal education at its best has always tried to be.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

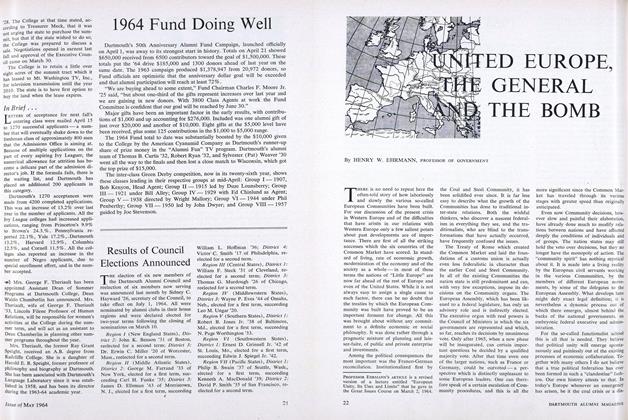

FeatureUNITED EUROPE, THE GENERAL AND THE BOMB

May 1964 By HENRY W. EHRMANN, -

Feature

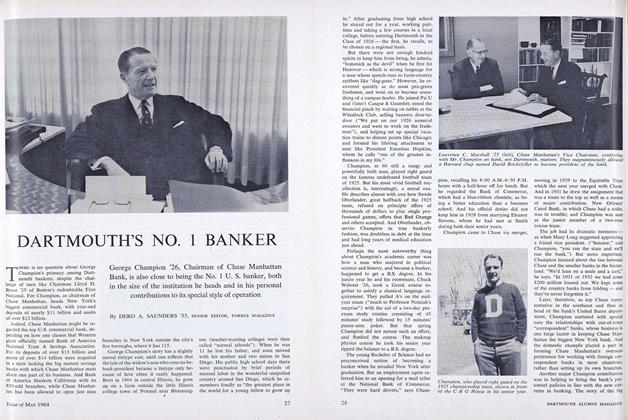

FeatureDARTMOUTH'S NO. 1 BANKER

May 1964 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35, -

Article

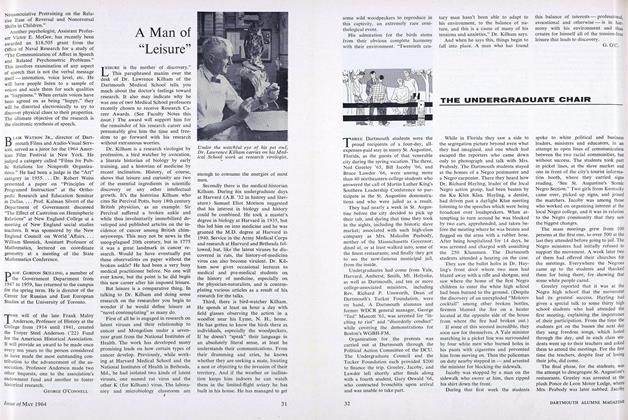

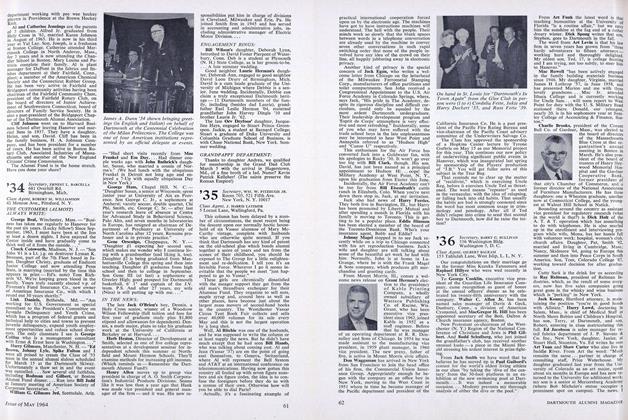

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

May 1964 By BARRY C. SULLIVAN, GILBERT BALKAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1964 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1964 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, JOHN s. MAYER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA BRIGHT FUTURE

July/Aug 2010 -

Feature

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

DECEMBER 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureWhitewater Racing Gains New Status

OCTOBER 1969 By JAY EVANS '49 -

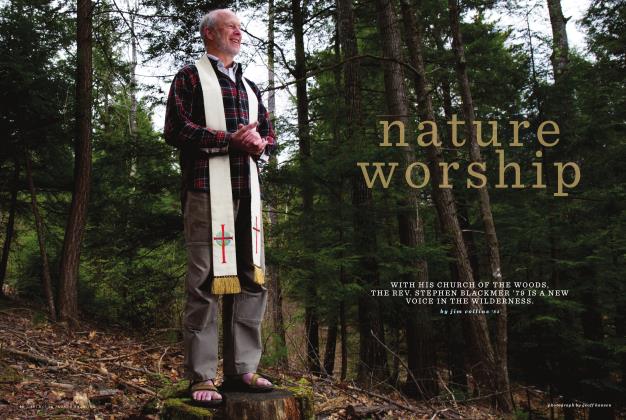

COVER STORY

COVER STORYNature Worship

MAY | JUNE 2019 By jim collins ’84 -

Feature

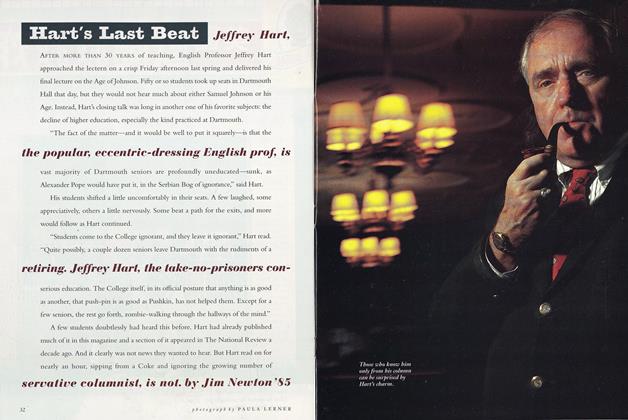

FeatureHart’s Last Beat

NOVEMBER 1992 By Jim Newton ’85 -

Feature

FeatureFirst

MAY | JUNE 2016 By Judith Hertog and Lexi Krupp ’15