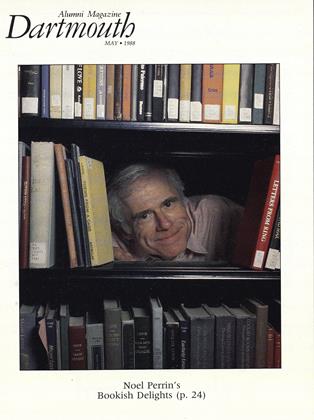

In Baker Library, a professor discovers the joys of straying beyond the literary canon.

SINCE William Caxton published the first book in English in 1475, some five or ten million English-language works have appeared. Of these a few thousand are recognized classics, ranging from "The Canterbury Tales," published by Caxton himself in 1478, up to, say, the complete poetry of Robert Frost, published in a definitive edition in 1969. They need no advertising. A few thousand more are current works of known merit. They too can look after themselves. But that leaves a large category of books just short of classic status that are known only to a handful of lucky readers. Almost anyone who reads a lot is apt to have come across at least one such book—something not in the canon, not famous, maybe not even in print—but all the same a sheer delight to read. Many lifelong readers have a whole collection of such books.

It's not apt to be a formal collection, like the rows and rows of Civil War books sitting on the shelves of a Civil War enthusiast, or the long line of Faulkner novels (and books of stories and poems) possessed by someone who means to own everything Faulkner ever wrote. In fact, the owner isn't likely to think of it as a collection at all. It's merely the miscellaneous group of favorite books that he or she keeps urging friends to read. All that the books have in common is that the owner thinks they are wonderful.

My own collection, which for some years now I have thought of in formal terms, is no less miscellaneous for that. There are books by Americans, by Englishmen and women, by an Italian diplomat and a Dutch resistance fighter (who both wrote in English), by a pair of Russian brothers, by a Japanese monk. There are 16 novels, five memoirs, four books of short stories and four of essays, a diary, a volume of letters written to an English knight, a book of animal sto- ries, a science fiction novella, a book of fables. I think they are all wonder- ful.

The collection—still unconscious of itself then—got its start almost 30 years ago, back in 1960. The man who was then the librarian of Dartmouth Col- lege, Richard Wedge Morin, provided the stimulus, though he had no idea he was doing so. On occasion he would invite a senior member of the faculty to pick five favorite books and to write a paragraph about each one explaining what seemed special about it. The books then got displayed in a big glass case in the main library cor- ridor, each with its explanatory para- graph pinned beside it. Lots of students coming down the corridor would stop and look. Colleagues gen- erally took a peek too.

One fall day I stood looking at the five books chosen by John Wolfenden, the New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry. Mr. Wolfenden was one of the two great luminaries of the chem- istry department, an Englishman whom Dartmouth had lured away from Oxford a few years earlier. I was a young instructor in the English de- partment, and I had never even met him.

Three of his choices I have forgotten, but the other two I remember vividly. They were kids' books, American kids' books. By some woman I had never heard of, named Laura Ingalls Wilder. (This was 14 years before "Little House" went on television.)

It seemed wildly improbable that an English scientist would use two of his five slots for children's books written in the colonies, when he could have been plugging some major work by Sir Humphrey Davy or showing off his fa- miliarity with Robert Boyle's "Skepti- cal Chemist," that hit of the year 1661. It made me curious. Though I wasn't even married at the time, let alone a father with children to read aloud to, I promptly went to the town library and checked out "Little House on the Prairie." I equally promptly fell in love with Mrs. Wilder's wonderful lucid style.

Young instructors pretty much live day-to-day and can no more imagine themselves old professors than young football players can imagine them- selves old coaches. Despite that, a little piece of my mind raced ahead to the time when (supposing I got tenure) I might get invited to pick five books for the case. I instantly knew that I would pick them Wolfenden style—that is, not trying to impress anyone with the loftiness of my taste or the rigor of my professionalism but merely calling at- tention to favorite books.

What's more, I already knew what one or two of them would be. For ex- ample, I owned and treasured a book called "The Journal of a Disappointed Man." I had stumbled on it in a sec- ondhand bookstore in New York, bought it for no better reason than that I liked the title, and then proceeded to read it three times in three years, find- ing it more poignant each time. No- body else I knew had ever heard of it, which gave me on one hand certain unattractive feelings of superiority and on the other an authentically generous wish to share my pleasure.

J A Another book I could imagine put- ting in the case was an obscure novel about the American Revolution. Au- thor unknown. Title: "The Adventures of Jonathan Corncob, Loyal American Refugee." I didn't own a copy, because the book had been out of print for about 175 years, and used copies were not something you were likely to find in a secondhand bookstore. Indeed, very unlikely, since there were then only about a dozen copies in the whole United States.

I had become aware of Mr. Corncob back when I was a graduate student. I was languidly skimming a book about Tobias Smollett, the eighteenth-cen- tury English novelist, because I had a paper to write and needed ideas. The book quoted a lot of eighteenth-cen- tury reviews, one of which discussed not only Smollett but also this new (in 1787) novel about the American Rev- olution. What most caught my eye was a complaint the reviewer made. He said that "Jonathan" was quite funny but unfortunately lacked "Smollett's decency."

Smollett's decency! The Victorians didn't know he had any. If "Jonathan" were even worse, I could hardly wait to read it. After some difficulty I got hold of a copy in the library of the New York Historical Society, and did read it. Did not find it particularly obscene (though I could see right away what upset the reviewer); did find it strik- ingly funny. A genuine minor master- piece. Worthy of a spot in my display case, if I ever got to have one.

I didn't. I missed by 20 years. I had been teaching at Dartmouth for only about 18 months and had not even ad- vanced to assistant professor when a new librarian took over. The faculty displays ceased. I nearly forgot about them—except that when I did marry and come to have children, I certainly remembered Laura Ingalls Wilder. I had the "Little House" books ready and waiting to read before my elder daughter turned four, and I did not forget how I came to know they ex- isted. And once in a while, when I stumbled across some minor Victorian novel such as "The Semi-Attached Couple," read it and was enchanted, a memory surfaced. I would think of the display case and wish that it still got used for exhibiting faculty favor- ites.

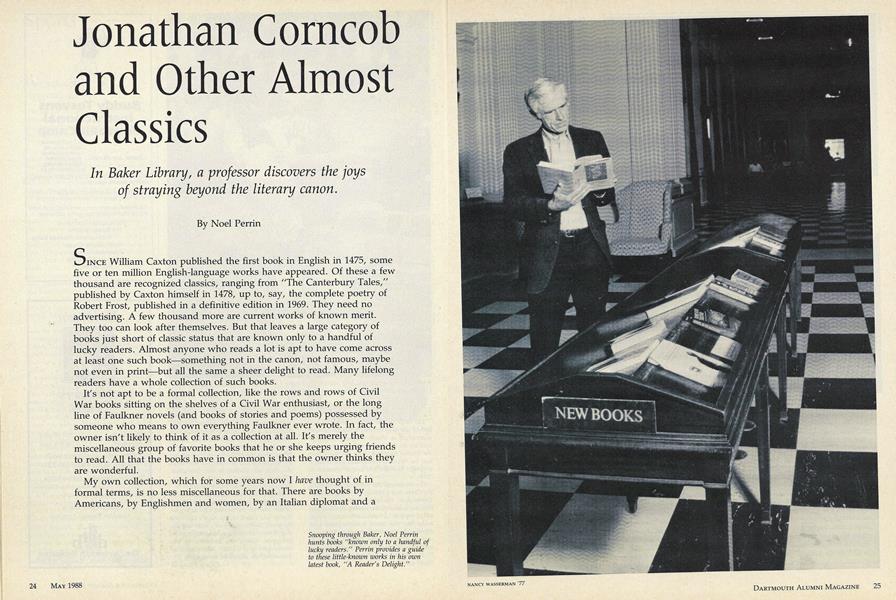

Snooping through Baker, Noel Perrinhunts books "known only to a handful oflucky readers." Perrin provides a guideto these little-known works in his ownlatest book, "A Reader's Delight."

During English Professor Perrin's three decades at Dartmouth he has written some booksof his oivn. Their subjects range from maple sugaring to Japanese history.

This article is adapted from "A Reader'sDelight" with permission of UniversityPress of New England. © 1988 by NoelPerrin.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

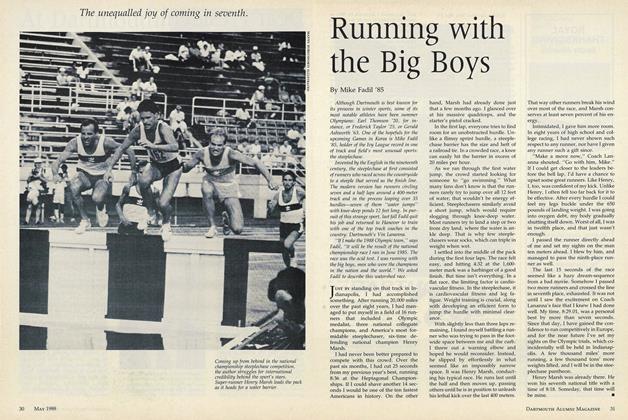

FeatureRunning with the Big Boys

May 1988 By Mike Fadil '85 -

Feature

FeatureAt Dartmouth, the Intellectual Is on the Margin

May 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Feature

FeatureDear President Freedman...

May 1988 By Tom Bloomer '53 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Writers Approve Review's Tongue-Lashing

May 1988 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorResponse: The Real Women's Issues

May 1988 By Mary G. Turco -

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

May 1988 By Jay Heinrichs

Noel Perrin

-

Books

BooksTHE LOST ART.

DECEMBER 1963 By NOEL PERRIN -

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleMinor Issues

MAY 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleDo Good Computers Make Good Writers?

APRIL 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

SEPTEMBER 1997 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONSkating on Thin Ice

MARCH 2000 By Noel Perrin