WITH the one hundredth anniversary of the commencement of the American Civil War soon to be upon us, publishers' lists are even more bristling than usual with historical and biographical volumes dealing with the events and personalities of that great conflict. Not only are many new books of present-day scholarship being issued, but also new editions are appearing of some of the important, but long out-of-print, works that form the heart of the massive body of literature of the war.

One of the books currently attracting attention and interest is The Battle ofGettysburg by Frank Aretas Haskell (Dartmouth 1854), republished early last month by Houghton Mifflin, with an introduction and editorial commentary by Pulitzer-Prize historian Bruce Catton.

Written in the immediate wake of the famous battle - within two weeks' time, so that the particulars of those momentous three days were vividly remembered and passionately felt - and by a Union officer who was in the very thick of the action, the account is, as its editor asserts, a genuine classic of its kind: one that "offers an understanding and an emotional experience that can be had from few other Civil War books."

BORN in Tunbridge, Vermont, on July 13, 1828, Franklin Aretas Haskell (in later life he used the shortened form of his given name) entered Dartmouth in the fall term of 1850 at the age of 22 from Columbus, Wisconsin.

In college he stood high scholastically. Edwin David Sanborn, then professor of Latin, whose impressions of his students he candidly jotted down in notebooks that still survive, observed of him: "Haskell, Franklin A. - improved greatly in college, ranked well as a scholar, was ambitious as Lucifer & possibly mischievous & irregular."

He was for a time president of his class, as is evidenced by an entry in a volume of secretaries' minutes of the spirited senior-year meetings of '54, a passage which records with mock poignancy and gravity his resignation of that office.

As was common among the undergraduates of his time, Haskell apparently taught school during the winter terms. One of his classmates many years later wrote of this feature of their collegiate years:

"I presume that out of our sixty-one there were never half a dozen present in college at any winter term. ***No matter how we have divided up into professions and business, we were almost all teachers during the winter term of our college life.

"I do not think that we spent any time more profitably to ourselves. The lament of these days that a college graduate has yet to learn to adapt himself to life was not in place in our day. A man who managed a village school indoors, and the rest of the folks outdoors, every winter, had the best discipline possible as introduction to the activities of any life.

"It is not any wonder that Haskell was a better disciplinarian than any other colonel who took a regiment from Wisconsin during the war, albeit several were West Point graduates...

In July of 1854 Haskell's class was graduated. They numbered 57 strong: 28 from New Hampshire, ten from Vermont, seven from Massachusetts, five from Maine, two each from Connecticut and Ohio, one from Rhode Island, an Indian of the Choctaw Nation, and Haskell himself, who was the sole representative of Wisconsin.

Their commencement season was noteworthy for the establishment in that year of Class Day exercises, which had not previously been a part of Dartmouth's observances.

Another innovation, and one that caused a minor stir, was the boycotting of Phi Beta Kappa by all but six of the seniors, "deeming the society a humbug, as it is here conducted." It seems very likely that Haskell would have been one of those elected had it not been for '54's firm resolution to decline such membership.

At this period commencement speakers were selected, completely without reference to their scholarly qualifications, by drawing lots, and their parts were assigned to them. Haskell was one of those chosen under this system, and, indeed, he was listed as the first orator, with a part entitled "The Real and Ideal - their relation to Art," in a program that included two dozen learned presentations on such diverse subjects as "The second Funeral of Napoleon," "The Literature of the extreme Northern Nations," "The importance of a Christian Spirit in scientific studies," and "The Wealth of New England in her Mountains and Rivers."

The press was warm in its praise of the discourses of the day. The New YorkTribune declared that the speakers "manifested more oratorical and general ability and more comprehensive views than are usually met with at college commencements," while The Times reported that they "made an excellent impression both by their manner and matter." The latter paper, however, provoked some indignation on the part of the undergraduates by leading off its account with the observation that the graduating class not only contained an extraordinary quantity of talent, but also "an unusual amount of self-esteem." It was a cutting remark that did not fail to elicit a sharp response from a '54 spokesman.

FOLLOWING his graduation, Frank Haskell went to Madison, Wisconsin, where he studied law, and he subsequently set up in practice there in partnership with Judge J.P. Atwood.

One who remembered him from those brief years of legal activity before the war, recalled nearly a generation afterward that, "As a lawyer he was gifted with a good deal more than ordinary ability. He was strong, acute, and logical, but modest and unpretentious. At a bar which was adorned with many very gifted members of the legal fraternity he was recognized as a young man of bright prospects, and had he lived would have won high rank in his profession. He was a true gentleman everywhere, at the bar, in the social circle, and all other places. He could not be otherwise, for nature had formed him so."

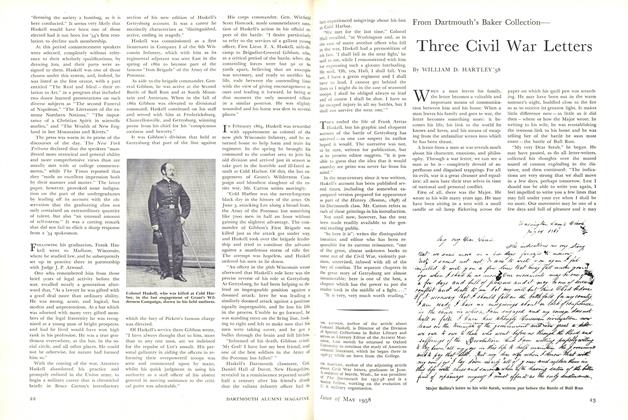

With the coming of the war, Attorney Haskell abandoned his practice and promptly enlisted in the Union army, to begin a military career that is chronicled briefly in Bruce Catton's introductory section of his new edition of Haskell's Gettysburg account. It was a career he succinctly characterizes as "distinguished, active, ending in tragedy."

Haskell was commissioned as a first lieutenant in Company I of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, which with him as its regimental adjutant was sent East in the spring of 1862 to become part of the famous "Iron Brigade" of the Army of the Potomac.

As aide to the brigade commander, General Gibbon, he was active at the Second Battle of Bull Run and at South Mountain and Antietam. When in the fall of 1862 Gibbon was elevated to divisional command, Haskell continued on his staff and served with him at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg, winning praise from his chief for his "conspicuous coolness and bravery."

It was Gibbon's division that held at Gettysburg that part of the line against which the fury of Pickett's famous charge was directed.

Of Haskell's service there Gibbon wrote, "I have always thought that to him, more than to any one man, are we indebted for the repulse of Lee's assault. His personal gallantry in aiding the officers in reforming their overpowered troops was seen and commented upon by many, whilst his quick judgment in using his authority as a staff officer of his absent general in moving assistance to the critical point was admirable."

His corps commander, Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, made commendatory mention of Haskell's action in his official report of the battle: "I desire particularly to refer to the services of a gallant young officer, First Lieut. F. A. Haskell, aide-decamp to Brigadier-General Gibbon, who, at a critical period of the battle, when the contending forces were but 50 or 60 yards apart, believing that an example was necessary, and ready to sacrifice his life, rode between the contending lines with the view of giving encouragement to ours and leading it forward, he being at that moment the only mounted officer in a similar position. He was slightly wounded and his horse was shot in several places."

IN February 1864, Haskell was rewarded with appointment as colonel of the new 36th Wisconsin Infantry, and he returned home to help form and train his regiment. In the spring he brought his command to the combat area to join his old division and arrived just in season to take part in the horrible and ill-fated assault at Cold Harbor. Of this, the last engagement of Grant's Wilderness Campaign and bloodiest slaughter of the entire war, Mr. Catton writes movingly:

"Cold Harbor was the never-forgotten black day in the history of the army. On June 3, attacking Lee along a broad front, the Army of the Potomac lost something like 7000 men in half an hour without gaining the slightest advantage. The commander of Gibbon's First Brigade was killed just as the attack got under way, and Haskell took over the brigade leadership and tried to continue the advance against a murderous storm of rifle fire. The attempt was hopeless, and Haskell ordered his men to lie down.

"An officer in the 36th Wisconsin wrote afterward that Haskell's role here was the precise reverse of his role at Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, he had been helping to defend an impregnable position against a doomed attack; here he was leading a similarly doomed attack against a position equally impregnable, and he lost his life in the process. Unable to go forward, he was standing erect on the firing line, looking to right and left to make sure that his men were taking cover, and he got a bullet through the brain and fell lifeless.

"Informed of his death, Gibbon cried: 'My God! I have lost my best friend, and one of the best soldiers in the Army of the Potomac has fallen!'"

Haskell's Dartmouth classmate, Col. Daniel Hall of Dover, New Hampshire, revealed in a reminiscence reported nearly half a century after his friend's death that the valiant infantry officer had in fact experienced misgivings about his fate at Cold Harbor.

"We met for the last time," Colonel Hall recalled, "at Washington and, as in the case of many another officer who fell in the war, Haskell had a premonition of his fate. 'I shall fall in the next fight,' he said to me, while I remonstrated with him for expressing such a gloomy foreboding. He said, 'Oh, yes, Hall, I shall fall. You see, I have a green regiment and I shall have to lead. I cannot get behind the lines as I might do in the case of seasoned troops. I shall be obliged always to lead and of course I shall be shot. I have so far escaped injury in all my battles, but I shall not survive the next one.'"

THUS ended the life of Frank Aretas Haskell, but his graphic and eloquent account of the battle of Gettysburg has survived —as one can suspect its author hoped it would. The narrative was not, to be sure, written for publication, but as its present editor suggests, "it is possible to guess that the idea that it would someday see print was never far from his mind."

In the near-century since it was written, Haskell's account has been published several times, including the somewhat expurgated version prepared for appearance as part of the History (Boston, 1898) of his Dartmouth class. Mr. Catton refers to each of these printings in his introduction.

Not until now, however, has the text been made readily available to the general reading public.

"So here it is": writes the distinguished historian and editor who has been responsible for its current reissuance, "one of the great, almost unknown books to come out of the Civil War, violently partisan, unrevised, infused with all of the fury of combat. The separate chapters in the great story of Gettysburg are almost innumerable; here is one of the best, a chapter which has the power to put the reader back in the middle of a fight...."

"It is very, very much worth reading."

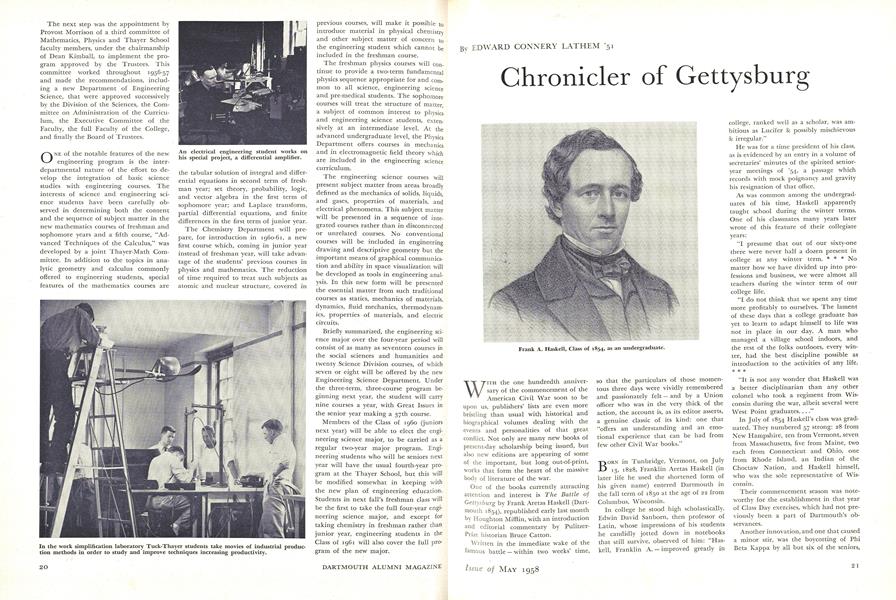

Frank A. Haskell, Class of 1854, as an undergraduate.

Colonel Haskell, who was killed at Cold Harbor, in the last engagement of Grant's Wilderness Campaign, shown in his field uniform.

MR. LATHEM, author of the article about Colonel Haskell, is Director of the Division of Special Collections in Baker Library and serves as Literary Editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Last month he returned to Oxford University to continue the study of American colonial literature, which he began there in 1956-57 while on leave from the College. MR- HARTLEY, author of the adjoining article about Civil War letters, graduates in June. A resident of Seattle, Wash., he was president of The Dartmouth for 1957-58 and is a Senior Fellow, working on the evolution of U.S. military organization.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThree Civil War Letters

May 1958 By WILLIAM D. HARTLEY '58 -

Feature

FeatureENGINEERING SCIENCE

May 1958 -

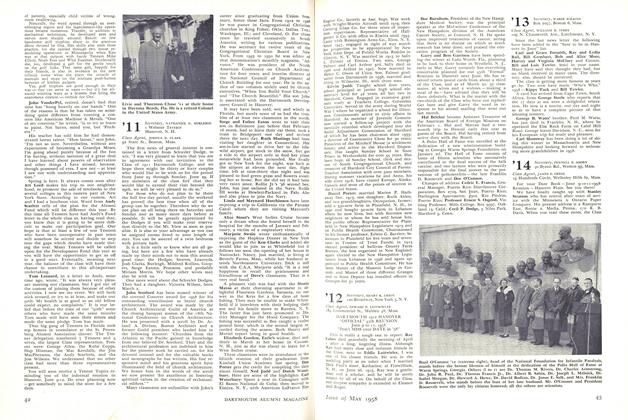

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1958 By CHESTER T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleWhat Is "New" in the Program?

May 1958 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1958 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Article

ArticleDaniel Webster's College Days

October 1952 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureJohn Wheelock's Laws of Conduct and Regulations for Students

January 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Article

ArticleApril 1865: Jubilation and Grief

April 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

FEBRUARY 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

Features

-

Feature

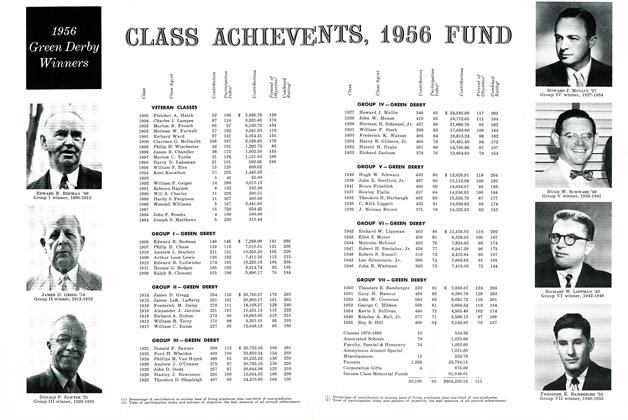

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVENTS, 1956 FUND

December 1956 -

Feature

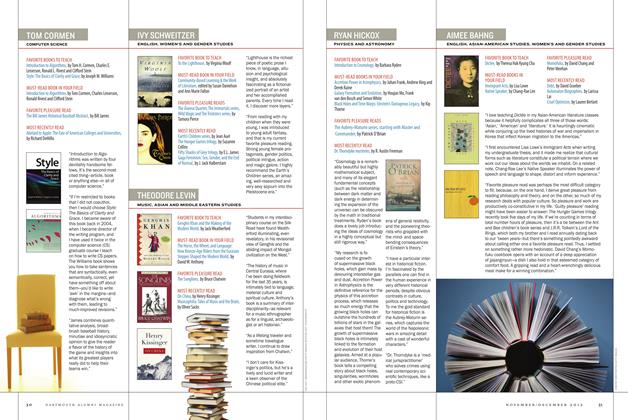

FeatureIVY SCHWEITZER

Nov - Dec -

Feature

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Feature

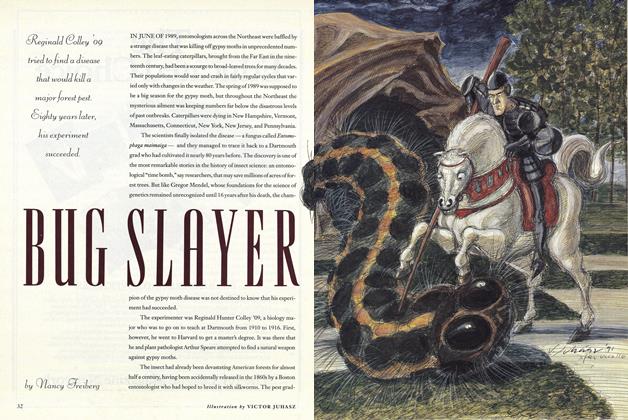

FeatureBUG SLAYER

JUNE 1991 By Nancy Freiberg -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Feature

Feature"Our trusty and well-beloved John Wentworth Esq., Governor"

DECEMBER 1968 By Susan Liddicoat