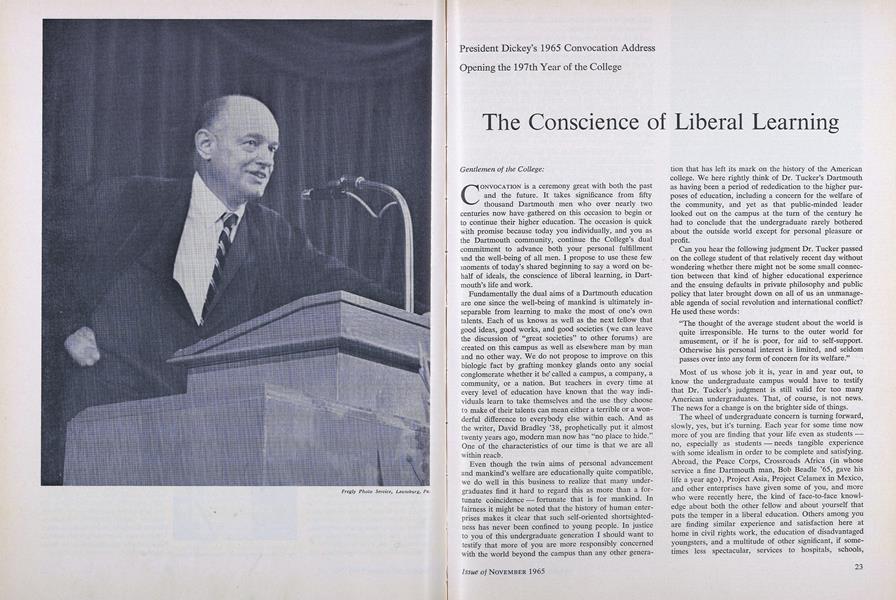

President Dickey's 1965 Convocation Address Opening the 197th Year of the College

Gentlemen of the College:

CONVOCATION is a ceremony great with both the past and the future. It takes significance from fifty thousand Dartmouth men who over nearly two centuries now have gathered on this occasion to begin or to continue their higher education. The occasion is quick with promise because today you individually, and you as the Dartmouth community, continue the College's dual commitment to advance both your personal fulfillment and the well-being of all men. I propose to use these few moments of today's shared beginning to say a word on behalf of ideals, the conscience of liberal learning, in Dartmouth's life and work.

Fundamentally the dual aims of a Dartmouth education are one since the well-being of mankind is ultimately inseparable from learning to make the most of one's own talents. Each of us knows as well as the next fellow that good ideas, good works, and good societies (we can leave the discussion of "great societies" to other forums) are created on this campus as well as elsewhere man by man and no other way. We do not propose to improve on this biologic fact by grafting monkey glands onto any social conglomerate whether it be" called a campus, a company, a community, or a nation. But teachers in every time at every level of education have known that the way individuals learn to take themselves and the use they choose to make of their talents can mean either a terrible or a wonderful difference to everybody else within each. And as the writer, David Bradley '38, prophetically put it almost twenty years ago, modern man now has "no place to hide." One of the characteristics of our time is that we are all within reach.

Even though the twin aims of personal advancement and mankind's welfare are educationally quite compatible, we do well in this business to realize that many undergraduates find it hard to regard this as more than a fortunate coincidence - fortunate that is for mankind. In fairness it might be noted that the history of human enterprises makes it clear that such self-oriented shortsightedness has never been confined to young people. In justice to you of this undergraduate generation I should want to testify that more of you are more responsibly concerned with the world beyond the campus than any other generation that has left its mark on the history of the American college. We here rightly think of Dr. Tucker's Dartmouth as having been a period of rededication to the higher purposes of education, including a concern for the welfare of the community, and yet as that public-minded leader looked out on the campus at the turn of the century he had to conclude that the undergraduate rarely bothered about the outside world except for personal pleasure or profit.

Can you hear the following judgment Dr. Tucker passed on the college student of that relatively recent day without wondering whether there might not be some small connection between that kind of higher educational experience and the ensuing defaults in private philosophy and public policy that later brought down on all of us an unmanageable agenda of social revolution and international conflict? He used these words:

"The thought of the average student about the world is quite irresponsible. He turns to the outer world for amusement, or if he is poor, for aid to self-support. Otherwise his personal interest is limited, and seldom passes over into any form of concern for its welfare."

Most of us whose job it is, year in and year out, to know the undergraduate campus would have to testify that Dr. Tucker's judgment is still valid for too many American undergraduates. That, of course, is not news. The news for a change is on the brighter side of things.

The wheel of undergraduate concern is turning forward, slowly, yes, but it's turning. Each year for some time now more of you are finding that your life even as students - no, especially as students - needs tangible experience with some idealism in order to be complete and satisfying. Abroad, the Peace Corps, Crossroads Africa (in whose service a fine Dartmouth man, Bob Beadle '65, gave his life a year ago), Project Asia, Project Celamex in Mexico, and other enterprises have given some of you, and more who were recently here, the kind of face-to-face knowledge about both the other fellow and about yourself that puts the temper in a liberal education. Others among you are finding similar experience and satisfaction here at home in civil rights work, the education of disadvantaged youngsters, and a multitude of other significant, if sometimes less spectacular, services to hospitals, schools, churches, prisons, or perchance just a lonely, hard-hit North Country farmer who "could use a little help" that he's above asking for. May I also mention that last year this student body once again began to get right with itself, or perhaps we should say began "to get with it," in supporting its own Campus Chest. I will not say more on this blind spot of the student community than to note for our remembering that the year the Campus Chest hit bottom The Dartmouth reported the meager results on one page and on another printed an editorial deploring the lack of care and concern on the part of college workmen that had permitted tree spray to drip onto student cars. That was a bad day for other things around here besides car finish.

It's been said that a dog needs at least a flea or two to remind him that he's a dog and perhaps an occasional bad day is useful in reminding us that we are human and also need to scratch a bit. However that may be, even on the days that sound bad our bet will be on you because one of your minor glories is that when it comes to ideals you generally play a better game than you talk. It is just because more and more of you in both action and utterance have shown that blatant sophomoric nihilism is neither a necessary or rewarding condition of American undergraduate life that your generation has within its reach the possibility of doing more to upgrade the experience we call "going to college" than all the curriculum committees that ever whistled their way up to the graveyard nobody wanted to move.

We ought not to be surprised that this developing taste on the part of more undergraduates for the contentions of life that take place beyond the intercollegiate stadia has not always been as manageable for the individual student or even as socially acceptable to some other people as "getting lost" on a big weekend. So long as it's not a son who has gotten ejected for doing too much of "what comes naturally," most adults are content to leave the defense of civilization against the aggression of "boys being boys" to the police or the dean. But a different attitude also "comes naturally," and most adults quickly lose that detached perspective when youth sees fit to challenge the structure and values of the adult community, the very community that in one form or another rightly feels it is giving these youths their education - or, perhaps even more to the point today, is giving them a student's deferment from fighting their country's battles in Viet Nam.

I need hardly tell you who know my convictions concerning the need for an open climate in an institution of higher learning that I would not have you silenced or dissuaded from any idealism by such difficulties, but neither would I have you learn arrogance and self-righteousness by being unaware or inconsiderate of all that a liberally educated man might be expected to try to understand as he takes his stand. I still remember the day this concern was clinched for me by a combative young man with whom I was discussing a perplexing problem of College policy. He gave the coup de grâce to my efforts with these words: "But you don't understand, sir, that if I understand everything I may not be able to maintain the position I have taken." He seemed to me to be hard aground on the rocks another student had approached and yet avoided with the wry observation that "the trouble with facts is there are so many of them."

All of which is to say that in anything very important there is usually more than meets the eye of any one of us. This truth, of course, can work its own mischief if it keeps a man from the commitment of decision simply because after measured consideration there is still something more that can be said - as there always is. But danger for danger, a man who would serve good causes greatly with mind as well as heart must have more to offer in the councils of men than merely the courage of his convictions. I suggest, therefore, that as you go about having your say you hold yourself to the hard discipline of having something to say. By so doing no great cause will suffer and your learning will prosper.

The two abiding ideals of our time, peace for the international community and justice for the individual, involve the two great dimensions of human experience: the universal and the particular. Both causes touch aspirations that are bounded neither by time nor place and yet both require solutions that are custom-made to fit a particular situation. Where could liberal learning in its breadth and depth be more at home? It's in the reconciliation of the universal and the particular that idealism comes to terms with realities - and vice versa. It is in this arena of great causes that our nation today faces the two worst tangles of idealism and realism we have had on the national agenda since the Civil War. At home a witch's brew of injustice, social blight, desperation and criminality has produced violence that must be forcibly suppressed even as it prods us to minister more justly and humanely to the children of those who are felled or imprisoned. Abroad, we stand committed once again to the national suppression of national aggression, a tragic regression for the entire international community from the earlier military action in Korea where, albeit mainly with U. S. might, communist aggression was resisted under the aegis of the United Nations. It may well be that under today's circumstances we could not have done differently. That, I believe, is now beyond useful debate. But if that be so, it assuredly is also so that what comes next is not beyond discussion. The terrible fact of war once again must be the taking-off point in civilized man's quest for a peace built on a more secure foundation than trial by battle of national power.

Any peace will be imperfect and every man's justice will be flawed. That is the way of ideals; it is their glory to be undying because their work is never done. Ideals are the abidingly good companions of life because they never lose their affinity for that unfinished side of man we call his soul.

If the individual student ought to have a concern with ideals that go beyond self, it is not too much to say that the College must be so committed. The College embraces as many personal purposes as there are men and women within its community. These personal purposes brought each of us to Dartmouth, but they did not bring Dartmouth to us. The institutional purpose on which Dartmouth was founded and has grown great has always been beyond being the private possession of any one of us. The purpose of an historic institution is to be found in its life as well as its charter and so it is here, but even in respect to the written word of her founding purpose Dartmouth is a creature of idealism. By her Charter she is committed to "all parts of Learning which shall appear necessary and expedient for civilizing and christianizing Children of Pagans. . . Those words, of course, were originally aimed at Indian youth but now as then Dartmouth has taken a cosmopolitan view of "Pagans." However each age may interpret for itself the reach of those two wonderfully embracing words "civilizing and christianizing," it is not open to doubt that in their broadest reach they enjoin on any man who serves or accepts the purposes of this institution an abiding concern for the advancement of the great ideals of human experience. This is perhaps the most compelling reason why in the curriculum, in extracurricular activities, in standards of conduct and performance the College must hold to a sense of institutional purpose that serves all men precisely because it reaches beyond the private interest of each of us. This is why your personal purposes and Dartmouth's purposes while complementary to each other are not necessarily the same. This is why we have such college-wide concerns as the distributive and degree requirements of the curriculum, the Great Issues Course, the Hopkins Center, and the Tucker Foundation, each in its own area aimed at fulfilling Dartmouth's primary obligation to human society by helping you to be fulfilled in all good things.

Before we turn from this talk of ideals and purposes to the realities of our respective daily duties may I leave a suggestion with you for later consideration by the appropriate agencies of the faculty and student government. As we go forward this year with our planned review of the curriculum for the junior and senior years, including particularly Great Issues, I believe there may be an opportunity for another pioneering move that would both serve our concern for the public-mindedness of our graduates and advance significantly the ideal of independence in learning here at Dartmouth.

I will put my suggestion in the form of a question: are we ready on both sides of this academic community, faculty and student body, to give fuller effect to the basic aims of the Great Issues Course by turning over to a student steering committee the responsibility for planning and administering the program of the course, leaving to a faculty advisory committee the setting of examinations and oversight of the experiment? Manifestly any such project would require a lot of "getting down to cases" and at least a year of preparation. I raise the question in this context because I believe that such educational venturing and such a further call on our faith would be good for those ideals and purposes I have commended to you and to myself today.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

Fregly Photo Service, Lewisburg, Pa.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

November 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44, -

Feature

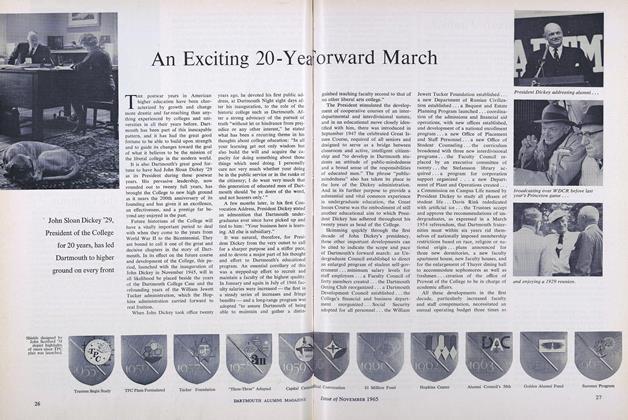

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

November 1965 -

Feature

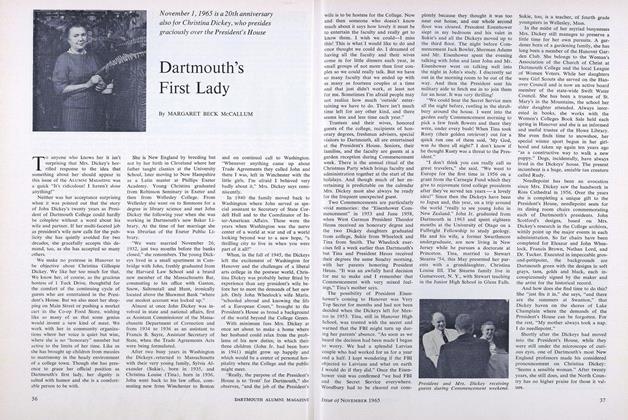

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

November 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

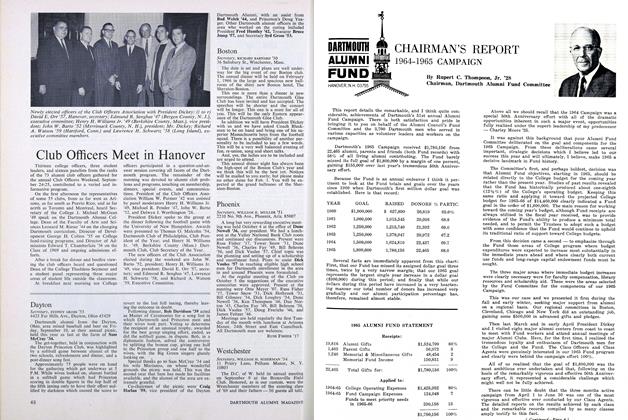

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

November 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

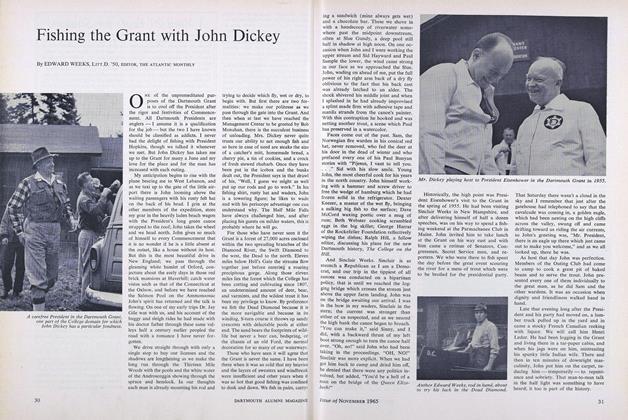

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

November 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50, -

Feature

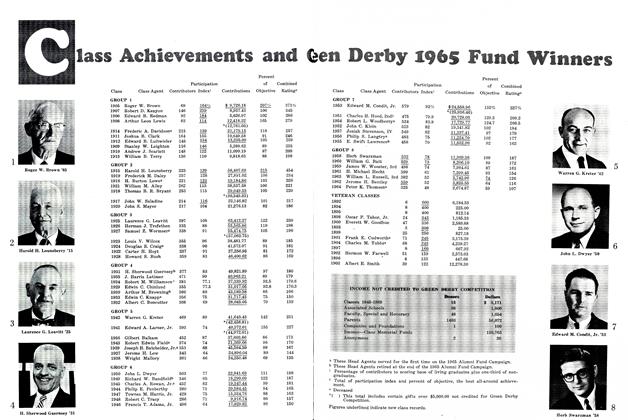

FeatureClass Achievements and Green Derby 1965 Fund Winners

November 1965

Features

-

Feature

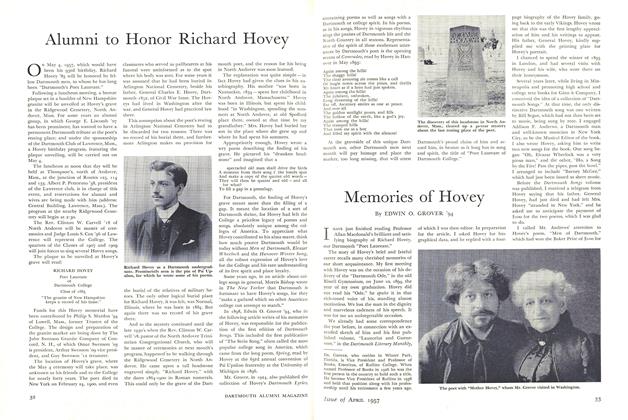

FeatureAlumni to Honor Richard Hovey

April 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe Ivy League schedule for 1972 ... and some showdown games

OCTOBER 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCarolyn Salafia '77

March 1993 -

Feature

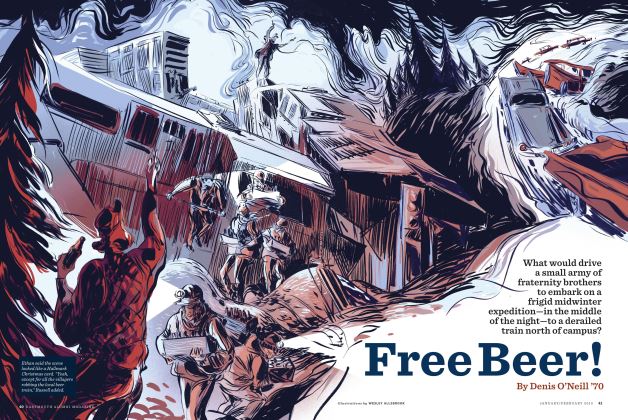

FeatureFree Beer!

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Denis O'Neill ’70 -

FEATURE

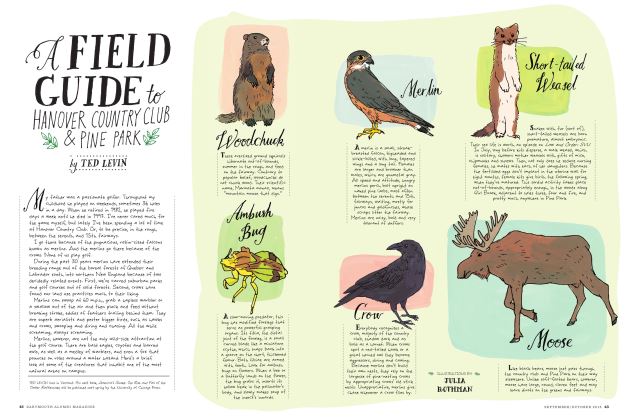

FEATUREA Field Guide to Hanover Country Club & Pine Park

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By TED LEVIN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO CONVINCE YOUR CLASSMATES TO FORK IT OVER

Jan/Feb 2009 By TROY STEWART '07